His papers throughout the 1940s and 50s slowly convinced some other scientists of the need for organized research.

Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Guy Stewart Callendar (9 February 1898 – 3 October 1964) was an English steam engineer and inventor.[1] His main contribution to human knowledge was developing the theory that linked rising carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere to global temperature. In 1938, he was the first to show that the land temperature of Earth had risen over the previous 50 years.[2] This theory, earlier proposed by Svante Arrhenius,[3] has been called the Callendar effect. Callendar thought this warming would be beneficial, delaying a “return of the deadly glaciers.”[4]

Early Life, Family, and Education

Callendar was born in Montreal in 1898, where his father, Hugh Longbourne Callendar, was Professor of Physics at McGill College (now McGill University). An expert in thermodynamics, Hugh Callendar returned to the United Kingdom with his family upon being appointed Quain Professor of Physics at University College London, before moving on after four years to take up a personal chair at Imperial College London.[5] His children grew up in an intellectually fertile environment, with visits at home from various members of the scientific elite.

When Guy was five he was left partially blinded after his elder brother Leslie stuck a pin in his left eye. In 1913 he enrolled at St Paul’s School, but left two years later following the start of World War I. Unfit for war service because of his blindness, he instead went to work in his father’s laboratory at Imperial College as an assistant to the X-ray Committee of the Air Ministry, where he was involved in testing a variety of apparatus, including aircraft engines at the Royal Aircraft Factory (later Establishment) in Farnborough.[6] In 1919 he began a course in Mechanics and Mathematics at City and Guilds College (part of Imperial), graduating with a certificate in those subjects three years later. This allowed him to commence full-time employment with his father, working on the properties of steam at high temperatures and pressures.

Career and Research

Callendar’s professional work on steam and pressure was conducted under the patronage of the British Electrical and Allied Industries Research Association, which represented turbine manufacturers. He later focused on research into batteries and fuel cells.[7] Although Callendar was an amateur climatologist,[2] he expanded on the work of several 19th century scientists, including Arrhenius and Nils Gustaf Ekholm as a hobby. Callendar published 10 major scientific articles, and 25 shorter ones, between 1938 and 1964 on global warming, infra-red radiation and anthropogenic carbon dioxide. Other scientists, notably Gilbert Plass and Charles Keeling, expanded upon Callendar’s work in the 1950s and 1960s.[7]

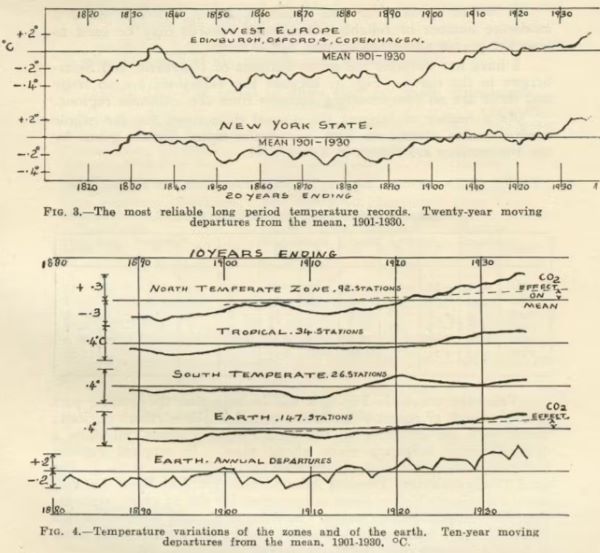

In 1938, Callendar compiled measurements of temperatures from the 19th century on, and correlated these measurements with old measurements of atmospheric CO2 concentrations.[3] He concluded that over the previous fifty years the global land temperatures had increased, and proposed that this increase could be explained as an effect of the increase in carbon dioxide.[8] These estimates have now been shown to be remarkably accurate,[2] especially as they were performed without the aid of a computer.[9] Callendar assessed the climate sensitivity value at 2 °C,[10] which is on the low end of the IPCC range. His findings were met with scepticism at the time; for example, Sir George Simpson, then director of the British Meteorological Society thought his results must be taken as a coincidence.[11]

However, his ideas did influence the scientific discourse of the time, which had been generally sceptical about the influence of changes in CO2 levels on global temperatures in the previous decades after debate over the idea in the early 20th century.[7] His papers throughout the 1940s and 50s slowly convinced some other scientists of the need to conduct an organised research programme on CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere, leading eventually to Charles Keeling’s Mauna Loa Observatory measurements from 1958, which proved pivotal to advancing the theory of anthropogenic global warming.[7] He remained convinced of the accuracy of his theory until his death in 1964 despite continued mainstream scepticism.[11]

Appendix

Endnotes

- Charles C. Mann (2018) Meet the Amateur Scientist Who Discovered Climate Change Wired.

- Hawkins, Ed & Phil Jones (2013) “On increasing global temperatures: 75 years after Callendar”, Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society.

- American Institute of Physics, The Discovery of Global Warming: The Carbon Dioxide Greenhouse Effect.

- Bowen, Mark (2006) Thin Ice, p. 96. New York, Henry Holt.

- “CALLENDAR, Hugh Longbourne”. Who’s Who & Who Was Who. Vol. 2022 (online ed.). A & C Black. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Fleming, James Rodger, “Callendar, Guy Stewart”. Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- Fleming, James Rodger (1998). Historical Perspectives on Climate Change. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Callendar, G. S. (1938) “The artificial production of carbon dioxide and its influence on temperature”, Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society.

- Fleming, J.R. (2007) The Callendar Effect: the life and work of Guy Stewart Callendar (1898–1964) Amer Meteor Soc., Boston.

- Archer, David; Rahmstorf, Stefan (2010). The Climate Crisis: An Introductory Guide to Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. p. 8.

- Hulme, Mike (2009). Why We Disagree About Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. pp. 50–52.

Further Reading

- Fleming, J.R. (2007) The Callendar Effect: the life and work of Guy Stewart Callendar (1898–1964) Amer Meteor Soc., Boston.

- Fleming, J.R. (1998) Historical Perspectives on Climate Change Oxford University Press, New York.

- Mann, Charles C. (2018) The Wizard and the Prophet: Two Remarkable Scientists and Their Dueling Visions to Shape Tomorrow’s World, Penguin Random House.

Originally published by Wikipedia, 12.04.2006, under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.