Far from being a simple pastime, the game functioned as a lived expression of values tied to strength, discipline, and collective effort.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Play, Power, and the Ancient Body

In the ancient Mediterranean world, physical play was not a trivial pastime set apart from social meaning. Games functioned as embodied expressions of cultural values, shaping how communities understood strength, discipline, cooperation, and aggression. Among these practices, harpastum occupies a distinctive place. Played informally by soldiers and civilians alike, it emphasized bodily control, tactical awareness, and forceful engagement rather than spectacle. Unlike the regulated contests of the arena, harpastum unfolded within everyday life, making it a revealing lens through which to examine ancient attitudes toward the body and power.

Roman culture attached deep significance to physical capability. Strength, endurance, and readiness for confrontation were not merely athletic virtues but social and moral ones. Harpastum aligned closely with these ideals. Its roughness was not incidental but integral, normalizing bodily collision and competitive struggle as legitimate forms of recreation. In this sense, the game did not simply entertain; it rehearsed cultural expectations about dominance, resilience, and collective action. Play became a space where values associated with citizenship and masculinity were enacted rather than abstractly taught.

The importance of harpastum is further clarified by its contrast with formal athletic and gladiatorial events. Arena spectacles separated performers from spectators, concentrating violence into ritualized displays controlled by elite power. Harpastum, by contrast, dissolved that boundary. It required participation, not observation. Its informal settings, minimal equipment, and flexible organization allowed it to circulate widely across social contexts. This accessibility made it a form of lived physical culture, embedded in daily routines rather than confined to festivals or state-sponsored events.

What follows argues that harpastum should be understood as a cultural practice that linked play to power through the disciplined use of the body. Derived from Greek ball games yet reshaped by Roman values, it reveals how physical recreation reinforced social norms while providing pleasure and communal bonding. By examining harpastum as an expression of everyday physicality rather than organized sport alone, we gain insight into how ancient societies used play to train bodies, negotiate violence, and articulate collective identity.

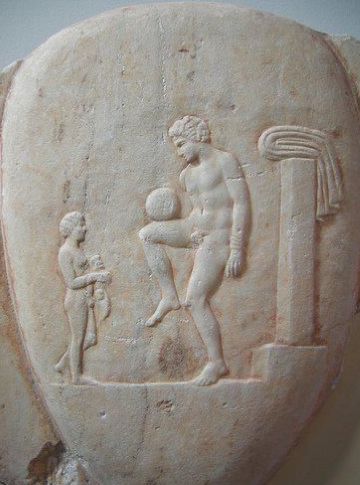

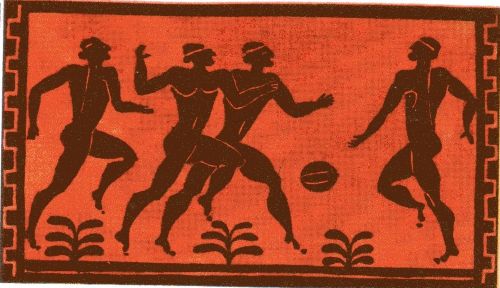

Greek Origins: Episkyros and Competitive Ball Play

The Roman game of harpastum did not emerge in isolation but developed from earlier Greek traditions of competitive ball play, most notably episkyros. In Greek athletic culture, ball games occupied a marginal yet revealing space alongside formal contests such as wrestling and racing. They were less ritualized and less prestigious than Olympic events, but they offered opportunities for agility, coordination, and tactical thinking. Episkyros exemplified this tradition, emphasizing territorial movement and collective effort rather than individual display.

Descriptions of episkyros indicate a game structured around spatial control. Two teams competed across marked boundary lines, attempting to force the ball past the opposing side’s line through passing, deception, and physical resistance. Unlike later Roman adaptations, the Greek version appears to have allowed greater use of the feet alongside the hands, though the precise balance remains debated. What is clear is that the game required constant motion and cooperation, rewarding teams that could coordinate movement rather than rely on brute force alone.

Greek attitudes toward athletic play shaped the character of episkyros. While physical contact was accepted, it was typically framed within ideals of balance, proportion, and skill. The game reflected a broader Greek fascination with harmony between mind and body, where athletic competition served as a training ground for discipline and self-mastery. Violence was present but moderated, integrated into a cultural emphasis on controlled exertion rather than overwhelming domination.

When Roman culture encountered episkyros, it inherited these structural elements while reinterpreting their meaning. The emphasis on territory, possession, and teamwork carried over directly into harpastum. At the same time, Roman preferences for intensity and confrontation pushed the game toward greater physical aggression. Understanding episkyros is therefore essential for tracing how Greek recreational practices were adapted to suit Roman ideals, transforming a competitive ball game into a more forceful expression of collective physical power.

From Greece to Rome: Cultural Transmission and Adaptation

The transition from Greek episkyros to Roman harpastum illustrates a familiar pattern of cultural transmission in the ancient Mediterranean: adoption followed by intensification. Roman society absorbed Greek physical practices with enthusiasm, yet rarely preserved them unchanged. Athletics, philosophy, and art were all reinterpreted through Roman values that emphasized discipline, utility, and dominance. In the case of ball games, this process transformed a contest oriented toward balance and skill into one that foregrounded force, endurance, and tactical disruption.

Roman adaptations of episkyros reflect a cultural environment less concerned with aesthetic harmony and more invested in physical assertion. While Greek athletic ideology prized moderation and symmetry, Roman physical culture favored resilience under pressure and the capacity to impose one’s will. Harpastum amplified bodily contact, encouraging grappling, tackling, and aggressive contest for possession. The game thus aligned more closely with Roman ideals of toughness and readiness for confrontation, qualities prized in both civic life and military service.

This transformation also altered the social meaning of play. In Greek contexts, ball games occupied a secondary position relative to formal athletic festivals tied to religious observance. Roman harpastum, by contrast, thrived as an informal pastime embedded in everyday life. It did not require institutional sponsorship or ceremonial framing. Soldiers played it during periods of rest, and civilians engaged in it as communal recreation. This shift reflects the Roman tendency to integrate physical discipline into routine experience rather than confine it to ritualized events.

Cultural adaptation, therefore, did not simply change the rules of the game. It reoriented its purpose. Harpastum became a medium through which Roman society rehearsed collective aggression, spatial control, and physical cooperation. The Greek inheritance of territorial play and teamwork remained intact, but it was recast within a Roman framework that treated bodily struggle as both pleasurable and socially formative. Through this process, a Greek game evolved into a distinctly Roman expression of power enacted through play.

Rules, Objectives, and Structure of Harpastum

Although no complete rulebook for harpastum survives, ancient descriptions allow a partial reconstruction of its objectives and structure. The game centered on possession of a small, hard ball and the effort to force it past an opposing boundary line. Victory depended less on scoring in a modern sense than on territorial domination and sustained control. Play was continuous and fluid, with few formal stoppages, encouraging endurance and adaptability rather than fixed set pieces.

The ball itself was crucial to the game’s character. Smaller and firmer than those used in many other ancient ball games, it could be gripped tightly and moved quickly under pressure. Handling rather than kicking dominated play, and footwork appears to have been minimal. This emphasis encouraged close bodily engagement, as players attempted to shield the ball, wrest it away from opponents, or disrupt passes through physical obstruction. Possession was constantly contested, producing a rhythm of sudden reversals and tactical improvisation.

Team organization further distinguished harpastum from more individualistic athletic contests. Players operated collectively, coordinating movement and positioning to create openings or overwhelm defenders. Feints and deceptive maneuvers played an important role, as success often depended on misdirecting opponents rather than overpowering them outright. Physical strength mattered, but so did anticipation and spatial awareness. The game rewarded those who could read the flow of play and adapt rapidly to changing conditions.

The relative absence of rigid formalization gave harpastum flexibility across settings. It could be played in open spaces without specialized infrastructure, allowing variation in team size and intensity. This adaptability contributed to its popularity among soldiers and civilians alike. The structure of the game emphasized participation and persistence over ceremonial regulation, reinforcing its role as an everyday practice of physical contest rather than a codified sport. In this way, harpastum embodied Roman preferences for functional physical engagement grounded in effort, control, and collective struggle.

Physicality and Controlled Violence

Rome’s Colosseum visitors can view the chambers that once held animals and contenders below the arena floor. / Photo by Senior Airman Alex Wieman, Wikimedia Commons

The defining feature of harpastum was its unapologetic physicality. Unlike many athletic contests that isolated strength, speed, or skill, this game fused them into a single, sustained struggle over possession. Players collided, grappled, and wrested the ball from one another in close quarters. Bodily contact was not an accidental byproduct of play but an essential mechanism through which the game functioned. To participate in harpastum was to accept physical confrontation as a normal and expected element of recreation.

The very name of the game underscores this emphasis. Derived from the Greek harpazō, meaning “to seize” or “snatch away,” harpastum encoded violence into its linguistic identity. Seizing the ball often required seizing the body of an opponent, disrupting balance, grip, and momentum. Tackling and grappling were integral techniques, not violations of decorum. The game thus normalized a form of controlled violence in which aggression was channeled toward a shared objective rather than unrestricted harm.

This violence, however, was structured and bounded. While rough, harpastum was not a chaotic brawl. Participants operated within an implicit understanding of limits shaped by custom rather than codified rules. Injury was possible, even likely, but serious harm was not the aim. The distinction mattered. Roman culture accepted physical risk as a legitimate cost of masculine and civic formation, provided it occurred within recognizable frameworks of discipline and mutual participation.

The acceptance of bodily struggle in harpastum reflects broader Roman attitudes toward pain and endurance. Physical resilience was a moral quality as much as a bodily one. To withstand blows, resist fatigue, and continue competing under pressure signaled character. In this sense, the game trained players not only in movement and coordination but in the social expectation that strength included the capacity to endure discomfort without complaint.

Through its fusion of play and confrontation, harpastum occupied a space between sport and combat. It familiarized participants with bodily conflict while stopping short of lethal intent. This balance made it culturally acceptable and socially useful. By embedding controlled violence within recreation, Roman society cultivated aggression without unleashing it, reinforcing ideals of dominance, discipline, and collective order through the medium of physical play.

Harpastum and the Roman Military

The close association between harpastum and the Roman military was neither accidental nor symbolic. Roman soldiers played the game during periods of rest and encampment, integrating it into the rhythms of military life. In a world where armies marched long distances and fought in tight formations, physical conditioning was essential. Harpastum provided a form of training that was engaging, competitive, and adaptable to limited space, making it well suited to the conditions of military camps.

The game reinforced qualities central to Roman military effectiveness. Agility, balance, and spatial awareness were constantly tested as players navigated crowded conditions while protecting or contesting possession of the ball. These skills translated directly to battlefield movement, where soldiers needed to maintain formation, react quickly to shifting threats, and coordinate with nearby comrades. Harpastum trained bodies to move with purpose under pressure, cultivating habits of responsiveness rather than rigidity.

Teamwork was perhaps the most significant military parallel. Success in harpastum depended on coordinated action rather than individual heroics. Players learned to anticipate the movements of others, cover vulnerable positions, and exploit openings created by collective effort. This emphasis mirrored the Roman military ethos, which prized unit cohesion above personal distinction. The game rehearsed cooperation through competition, reinforcing the idea that strength emerged from disciplined collective action.

The physical confrontation inherent in harpastum also acclimated soldiers to bodily conflict without crossing into lethal violence. Grappling, resisting force, and maintaining control under physical stress prepared participants psychologically as well as physically for combat. By normalizing controlled aggression, the game reduced the shock of close-quarters struggle. Soldiers became accustomed to bodily contact, pressure, and fatigue in a context that remained recreational rather than fatal.

Harpastum further functioned as a mechanism for maintaining morale. Military life involved long stretches of monotony punctuated by moments of extreme danger. Games offered relief from routine while preserving discipline and readiness. Harpastum satisfied the need for diversion without undermining martial values. It allowed soldiers to expend energy, assert strength, and reinforce bonds, all within a framework that aligned with military identity.

In this way, harpastum occupied a hybrid role between play and preparation. It was not formal training imposed from above, but voluntary participation encouraged by its evident benefits. The game exemplifies how Roman military culture blurred the line between recreation and readiness. Through harpastum, the Roman army transformed leisure into an extension of discipline, using play to sustain bodies, morale, and collective cohesion in service of imperial power.

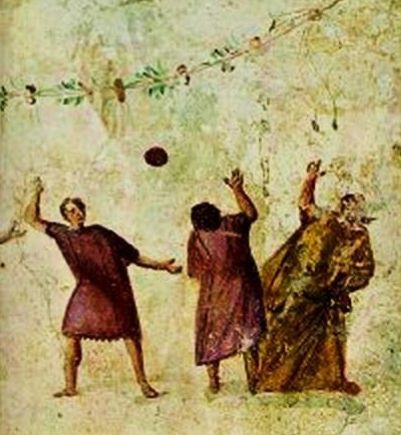

Civilian Play and Social Life

While harpastum held clear appeal for soldiers, it was not confined to military contexts. Civilians across the Roman world also played the game, incorporating it into daily life as a form of recreation and social interaction. Its minimal equipment and flexible structure allowed it to be played in open spaces, courtyards, and public areas without formal organization. This accessibility made harpastum a shared cultural practice rather than an elite or specialized pursuit.

Participation in the game appears to have crossed social boundaries. Youths, working men, and other non-elite participants could engage in play without the expense or institutional barriers associated with organized athletics. In this respect, harpastum differed markedly from spectacles staged in arenas, which reinforced social hierarchies through seating, sponsorship, and patronage. Civilian play emphasized participation over observation, creating opportunities for interaction that temporarily suspended distinctions of status.

The social dimension of harpastum extended beyond physical exertion. Games functioned as occasions for camaraderie, rivalry, and communal bonding. Regular play fostered familiarity and trust among participants, reinforcing local networks of association. The competitive yet cooperative nature of the game mirrored broader patterns of Roman social life, in which individuals navigated relationships shaped by both mutual dependence and assertive self-interest.

Harpastum also played a role in informal education. Younger participants learned physical coordination, discipline, and social norms through imitation and experience rather than instruction. The game transmitted expectations about endurance, cooperation, and acceptable aggression, embedding cultural values in embodied practice. Through repeated play, individuals absorbed lessons about collective effort and controlled conflict that aligned with Roman ideals of civic behavior.

As a form of civilian recreation, harpastum illustrates how physical play contributed to social cohesion in the Roman world. It offered an outlet for energy and competition while reinforcing shared understandings of strength, discipline, and belonging. By occupying spaces outside formal institutions, the game became part of the texture of everyday life, demonstrating how communal play served as both entertainment and social glue within Roman society.

Skill, Strategy, and Teamwork

Despite its reputation for roughness, harpastum was not a game of brute force alone. Success depended on a combination of physical ability and strategic intelligence. Players needed to read the movement of opponents, anticipate shifts in possession, and adjust positioning in response to rapidly changing conditions. Those who relied solely on strength were often outmaneuvered by teams that coordinated movement and exploited momentary openings.

Passing played a central role in maintaining possession. Quick, well-timed exchanges allowed teams to evade pressure and reposition the ball before opponents could respond. These passes were often accompanied by feints and misdirection, forcing defenders to commit prematurely or break formation. The effectiveness of such tactics lay in deception rather than domination, underscoring the importance of mental agility alongside physical power.

Spatial awareness was equally critical. Players needed to understand not only their own position but the configuration of the entire field. Maintaining advantageous spacing prevented opponents from collapsing around the ball carrier and enabled coordinated advances toward the opposing line. This awareness required constant communication, whether verbal or gestural, reinforcing the collective nature of the game. Individual brilliance mattered less than the ability to operate within a coordinated unit.

Teamwork in harpastum extended beyond offensive maneuvers. Defensive cooperation was essential for disrupting passes, isolating ball carriers, and forcing turnovers. Players had to balance aggression with restraint, knowing when to challenge directly and when to hold position. Effective defense relied on mutual trust, as overcommitment by one player could expose the team as a whole.

Through these dynamics, harpastum cultivated habits of collective problem-solving. Players learned to subordinate personal impulses to shared objectives, adapting tactics as circumstances changed. This blend of strategy and cooperation distinguished the game from purely combative contests. It transformed physical struggle into a disciplined collective endeavor, reinforcing the Roman valuation of coordinated effort as a source of strength and success.

Harpastum and the Genealogy of Modern Football Codes

Harpastum occupies an important place in the long and uneven history of contact ball sports. While it cannot be treated as a direct ancestor of any single modern game, its structural features anticipate key elements found in contemporary football codes. Possession, territorial advancement, physical contact, and coordinated team movement all form part of a lineage that stretches across centuries of informal play and cultural adaptation. Harpastum demonstrates that the basic grammar of these sports was established long before modern rules and institutions formalized them.

One of the clearest points of continuity lies in the emphasis on territory rather than scoring alone. Like rugby and association football, harpastum centered on advancing the ball across space under opposition pressure. Progress was incremental and contested, shaped by physical resistance and tactical maneuvering. This contrasts with sports focused primarily on isolated scoring moments and highlights a shared logic of sustained struggle over ground.

Physical contact provides another point of comparison. Harpastum permitted grappling and bodily obstruction, anticipating the controlled collisions of rugby and American football. Although modern codes impose strict regulations on tackling and contact, the underlying acceptance of physical confrontation as integral to play reflects an ancient inheritance. The difference lies not in the presence of contact, but in its codification and restriction through written rules and officiating.

At the same time, harpastum diverges significantly from modern games in its informality. It lacked standardized team sizes, fixed field dimensions, and formal enforcement mechanisms. These absences remind us that modern football codes emerged through processes of regulation, institutionalization, and commercialization. Harpastum represents an earlier stage in which play was governed by shared understanding rather than written law, allowing flexibility but also greater physical risk.

Understanding harpastum within this broader genealogy highlights continuity without collapsing difference. Modern football codes did not evolve in a straight line from Roman games, but they share fundamental human impulses toward competitive cooperation, physical challenge, and communal play. Harpastum stands as an early articulation of these impulses, offering insight into how bodily struggle and teamwork became enduring features of collective sport across cultures and centuries.

Conclusion: Play as Cultural Mirror

Harpastum reveals how deeply physical play was embedded in the social and cultural fabric of the Roman world. Far from being a simple pastime, the game functioned as a lived expression of values tied to strength, discipline, and collective effort. Through its emphasis on bodily control and confrontation, harpastum mirrored Roman ideals of power and resilience, translating abstract social expectations into physical experience. Play became a means of shaping bodies in accordance with cultural norms.

The game also illustrates how societies regulate violence by embedding it within structured activities. Harpastum allowed aggression to be expressed and managed rather than suppressed or unleashed without limit. By framing physical struggle as recreation, Roman culture normalized confrontation while reinforcing boundaries around acceptable conduct. This balance between force and control reflects a broader social strategy of cultivating dominance without chaos, revealing how play could serve as a tool of social order.

At the same time, harpastum fostered cooperation and communal identity. The game required coordination, trust, and shared purpose, reinforcing bonds among participants regardless of military or civilian context. These collective dimensions demonstrate that Roman physical culture was not solely about individual toughness but about integration into a disciplined group. Through repeated play, participants internalized lessons about teamwork and mutual reliance that extended beyond the field.

Viewed in this light, harpastum serves as a cultural mirror, reflecting how ancient societies understood the relationship between bodies, power, and community. Its legacy lies not in direct institutional descent but in the enduring human impulse to organize play around physical challenge and collective struggle. By examining harpastum as both recreation and cultural practice, we gain insight into how play has long shaped social values, revealing continuities between ancient and modern understandings of sport, discipline, and identity.

Bibliography

- Abdulsalam, Zahiah Sabah, Wafaa Hussein Abdulameer, and Jamal Sakran Hamza. “Analysis of the History of Ball Sports.” Journal of Sport Sciences 11:10 (2022): 1-9.

- Beard, Mary. SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome. New York: Liveright, 2015.

- Campbell, J. B. The Roman Army, 31 BC–AD 337. London: Routledge, 1994.

- Crowther, Nigel B. Sport in Ancient Times. Westport, CT: Praeger, 2007.

- Gardiner, E. Norman. Athletics of the Ancient World. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1930.

- Dunning, Eric. Sport Matters: Sociological Studies of Sport, Violence and Civilization. London: Routledge, 1999.

- Goldblatt, David. The Ball Is Round: A Global History of Football. London: Penguin, 2006.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian. The Roman Army at War, 100 BC–AD 200. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

- Hughson, John. “The Ancient Sporting Legacy: Between Myth and Spectacle.” Sport in Society 12:1 (2009): 18-35.

- Kyle, Donald G. Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2007.

- Malešević, Siniša. “Warrior Ethos and the Spirit of Nationalism.” Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research (June 2025): 1-18.

- Miller, Stephen G. Ancient Greek Athletics. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004.

- Poliakoff, Michael B. Combat Sports in the Ancient World. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987.

- Scanlon, Thomas F. Eros and Greek Athletics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Tanyeri, Levent, and Özge Sezik Tanyeri. “Ball Games in Ancient Rome: Trigon, Paganica, and Harpastum as Physical Culture and Pre-modern Team Sports.” European Journal of Physical Education and Sport Science 13:1 (2026): 25-38.

- Wiedemann, Thomas. Emperors and Gladiators. London: Routledge, 1992.

Originally published by Brewminate, 01.15.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.