The trial of Socrates is a foundational episode in the history of dissent. It exposes the fragility of democratic institutions when confronted by radical thought.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Socrates in the Shadow of the State

In 399 BCE, the philosopher Socrates stood before an Athenian jury of 501 men, accused of impiety and corrupting the youth. What followed was not merely a civic trial, nor even a philosophical drama, but an early rupture in the uneasy relationship between intellectual freedom and state power. The charges, clothed in legal rhetoric, were in fact deeply political. Socrates’ radical insistence on questioning, on dialectic, on never accepting a thing as settled merely because it was custom, became intolerable in a polis battered by war, self-doubt, and shifting ideological tides.

Athens had only recently emerged from the humiliating defeat of the Peloponnesian War and the brief but brutal oligarchy of the Thirty Tyrants. That trauma echoed in the city’s renewed desire for unity, stability, and cultural cohesion. In that moment of moral retrenchment, Socrates was an irritant. He embodied, in both method and manner, the disruptive voice of dissent. He was not tried for what he did so much as for what he represented: the perennial threat of thought unmoored from state purpose.

His death, by cup rather than sword, resonates still. It was not the execution of a subversive in the streets but the sanctioned silencing of a mind. Socrates’ trial is an origin point for philosophical martyrdom, but more than that, it inaugurates a historical pattern that repeats wherever regimes, democratic or otherwise, seek to legislate the limits of inquiry.

Philosophia as Provocation: The Method That Undermines

Socrates’ crime was not his doctrine, for he had none. Unlike the sophists he was so fond of undermining, he charged no fee, wrote no treatise, and offered no fixed program for the soul or the city. His method was aporia, the careful unraveling of others’ presumed knowledge. This made him dangerous. To question piety before a jury steeped in religious tradition, to destabilize ideas of virtue before the very class entrusted to cultivate it, was a provocation cloaked in polite inquiry.

Plato’s Apology captures the essence of this intellectual subversion. Socrates presents himself not as a corrupter, but as a gadfly, divinely mandated to sting the sluggish horse of the state into motion.1 This metaphor, almost offhand in the speech, is profoundly revealing. Athenian democracy, for all its celebration of citizen agency, required cohesion. Socrates’ questioning was not seen as civic participation but as destabilizing mockery.

Moreover, he did not merely critique individuals. He exposed the flimsy foundations of commonly held beliefs (piety, justice, citizenship) not through dogma, but by revealing contradiction and incoherence. In so doing, he made the Athenian citizen uncomfortably aware of how little he actually knew. Philosophical courage became social offense.

The Mechanics of Suppression: Jury, Assembly, and Ideological Policing

Athens prided itself on its democracy, yet it was that very democracy that condemned Socrates. His fate was not sealed by a tyrant, but by the votes of citizens acting under the color of law. The assembly, having absorbed years of conflict and betrayal, turned to the courts to restore order. In that context, intellectuals who challenged consensus became suspect.

The jury that condemned Socrates was not irrational. It was wounded, weary, and desperate for moral clarity. Socrates offered none. His refusal to apologize, to recant, to propose exile instead of death, was read as defiance. He left the jury with a terrible choice: affirm its authority or surrender to a man who denied its wisdom.2 They chose affirmation.

The process reveals the paradox of democratic societies. Institutions built to ensure free speech can, under sufficient stress, become tools of suppression. The trial of Socrates shows how easily civic instruments become ideological mechanisms, preserving not justice but the illusion of unity. The accusation of “corrupting the youth” functioned not unlike modern accusations of extremism or subversion, terms vague enough to ensnare inconvenient thinkers, yet resonant enough to mobilize public fear.

Death as Dialogue: Socrates’ Final Rebuttal

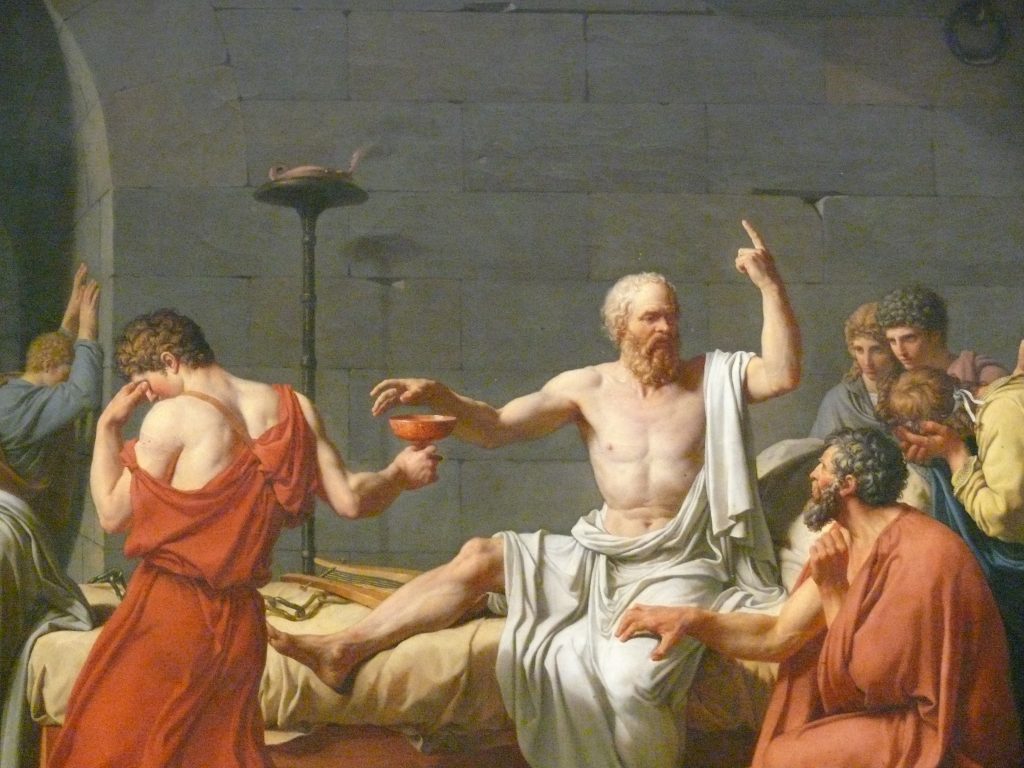

Socrates did not resist his fate, but he did resist its meaning. He accepted the sentence but denied its legitimacy. In his final words, he asked that a cock be offered to Asclepius, the god of healing.3 This gesture has long puzzled commentators. Was Socrates suggesting that death was a cure? That philosophy, taken to its limit, heals the soul even as the body dies?

The death of Socrates thus becomes not a defeat, but a final act of philosophical instruction. It is, paradoxically, the moment when he is most free. Refusing to flee, refusing to compromise, he embodies the very freedom that the city claimed to defend and yet could not tolerate.

His execution became a lens through which later thinkers – Plato, Xenophon, Cicero, Montaigne, and even Enlightenment liberals – examined the perils of political overreach into intellectual life. In each of these reflections, Socrates stood not as a martyr for belief, but as a martyr for method.

From Athens to the Academy: Echoes in Modern Thought Control

The fate of Socrates is not a relic of antiquity. In every era, intellectuals who challenge prevailing orthodoxies risk condemnation, not always by death, but by dismissal, censorship, or reputational ruin. Modern states, democratic and authoritarian alike, still seek to define the limits of acceptable thought, often through bureaucratic rather than judicial means.

In contemporary academia, the boundaries of inquiry may be policed through funding constraints, ideological gatekeeping, or social coercion. While no jury votes on who may speak, institutional culture often does. When inquiry becomes tethered to political expediency, the Socratic voice becomes once again suspect.

Socrates’ trial warns against the temptation to trade discomfort for order. His method demands that we live with the unease of unknowing, and his death reminds us that such unease is the cost of a genuinely open society.

Conclusion: The State and the Soul

The trial of Socrates is a foundational episode in the history of dissent. It exposes the fragility of democratic institutions when confronted by radical thought. Socrates died not because he was wrong, but because he refused to accept that right thinking must serve political ends.

His legacy is not a doctrine, but a stance, a refusal to cease questioning, even when the city demands silence. In honoring Socrates, we do not merely remember a man, but reaffirm the perilous necessity of philosophy in public life. The health of a society, like that of the soul, may be measured by how it treats its gadflies.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Plato, Apology, trans. G.M.A. Grube (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 2000), 30e.

- Thomas C. Brickhouse and Nicholas D. Smith, Socrates on Trial (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989), 187–88.

- Plato, Apology, 42c.

Bibliography

- Allen, Danielle S. Why Plato Wrote. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

- Brickhouse, Thomas C., and Nicholas D. Smith. Socrates on Trial. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989.

- Kraut, Richard. “Socrates.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta. Spring 2023. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2023/entries/socrates/.

- Ober, Josiah. Mass and Elite in Democratic Athens: Rhetoric, Ideology, and the Power of the People. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989.

- Plato. Apology, translated by G.M.A. Grube. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 2000.

- Reeve, C.D.C. Socrates in the Apology: An Essay on Plato’s Apology of Socrates. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 1989.

- Stone, I.F. The Trial of Socrates. Boston: Little, Brown, 1988.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.18.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.