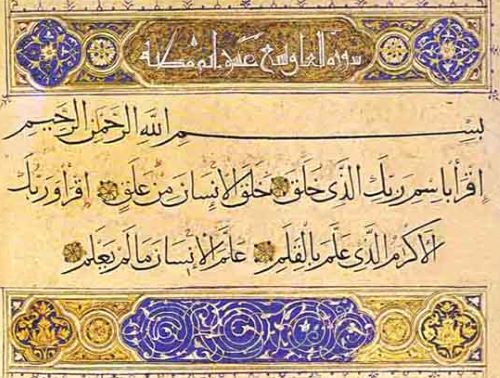

Only by 730 CE was something closely related to the teachings of the Qur’an commented in detail.

By Dr. Jesús Zamora Bonilla

Professor of Logic and Philosophy of Science

Dean, Faculty of Philosophy

Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED)

Introduction

Since the first half of the 19th century, philologists and historians have been examining the extant evidence about the origins of Christianism and Judaism, particularly studying the books of the Bible with the methods applied to any other old document. Though this research faced strong opposition both from most Christian denominations and from some of the most conservative layers of European and American societies, it is now commonplace (save perhaps within some stubborn Protestant and Jewish sects still attached to the dogma of inerrancy) to assume that the Bible was written by fallible and far from disinterested people, usually a very long time after the events narrated in it: e.g., several centuries in the case of the Pentateuch or Torah, and at least between four to eight decades in the case of the New Gospel. Contradictions, a mix of different authors within the same ‘books’, falsifications or mere recollection of previous mythologies, and so on, are now taken as part of the established philological knowledge about the Bible, no matter what moral or religious significance each reader is free to assign to such a fundamental work.

In the case of Islam, however, the situation is completely different, because two reasons that may seem to go in opposite directions. On the one hand, the resistance to take the Qur’an as an object of scientific study has been stronger in more than an order of magnitude in Islamic societies than what Biblical research was in the western countries. The persecution of Nasr Abu Zayd in Egypt, or the fact that some Islamic scholars (like Ibn Warraq) have to write under a pseudonym when expressing critical views about the literal truth of the Muslim Scripture, are a proof of how difficult still is to advance academic research on the Qur’an, not only in those countries but everywhere else. But, on the other hand, there is the traditional belief that, contrarily to the case of the Gospels, written by disciples one or two generations after Jesus Christ’s death, Islam was born “under the full light of history” (to use the famous phrase of mid-19th century philologist Ernest Renan): we seem to have a record of the life of Muhammad almost day by day, and of the whole circumstances under which the suras of the Qur’an were transcribed, collected and disseminated through the Islamic world within the following decades. This knowledge was orally transmitted by means of the so-called hadiths: sayings about the Prophet, recollecting his deeds or words and certified by a faithful chain (the isnad) of transmitters from some original witnesses.

In spite of this apparent confidence, contemporary scientific research on the origins of Islam is starting to switch off the ‘light’ Renan referred to. Here are, to begin with, some relevant dates to take into account. The Prophet Muhammad is supposed to have been born in Mecca (Arabia) by 570 C.E. The archangel Gabriel would have started to appear to him by 610, transmitting to the Prophet the verses of the Qur’an under the form of a recitation (which is what Qur’an means) from that time to almost Muhammad’s death. The Prophet would have formed a small community around him at Mecca, where the ‘living forces’ would have forced them to retire to exile (the Hijra) to Medina by 622, which is the year chosen by the Muslims to start their calendar. Muhammad died in 632, soon after recovering Mecca by the arms within the process of conquering most of the Arabian peninsula. In what is probably the most spectacular episode of conquest in all the human history (only paralleled by the Castilians in America and by Alexander the Great, but with a much bigger success in terms of political endurance), the followers of Muhammad took within the next thirty years (the time of the ‘Orthodox’ Caliphate, i.e., led by Caliphs that have been contemporaries of Muhammad as well as direct relatives of him) all Near East from Lybia to the limits of India, except Anatolia, and in the following four or five decades (the Ummayad Caliphate), the rest of North Africa, the Iberian Peninsula, and part of the India and Central Asia.

The question is that, in a similar way as the cosmological inflation of the universe seems to have erased almost all traces of what happened before it, making the geometry of space and time equally flat everywhere, the inflationary expansion of Islam during its first two centuries left at the end a vision of its own history that left almost no traces with which to contrast its historical pedigree. And the few things that we have about it are certainly surprising. Let’s see what contemporary Christian sources say about; in the next article we will examine the Arabic sources, and in the third part what philology can show about the Qur’an itself.

1) The first known written reference to an ‘Arab prophet’ is certainly almost contemporary of Muhammad, a book known as Doctrina Jacobi written in Palestine by a Christian monk between 634 and 640, who refer to a no-named ‘prophet’ that commanded the ‘Saracene’ conquering army (the term ‘Arab’ started to be used much later), and who complained that true prophets didn’t come with a sword. The main problem is that the author refers to that ‘prophet’ as still living and militarily active in Palestine, though the book was written after the supposed date of Muhammad’s death. Furthermore, the text mentions that the prophet-commander was announcing the imminent advent of the Messiah as well as his ‘holding the keys of the paradise’, two statements that are hardly part of the posterior Islamic faith.

2) Another book, this time written in Syriac by a monk called Thomas around ten years later, mentioned an army to which he refers as tayyaye d-Mhmt; ‘tayyaye’ is a Syriac name for the Arab nomads, and Mhmt can be, of course, a reference to the one they were following, so that the whole expression can be translated as ‘the Arabs of Muhammad’. One minor problem here is that the right transcription into Syriac would have been Mhmd, but more important is that the text does not say absolutely anything about this person… assuming that the expression is the name of a person, for Mhmd meant in Arabic just ‘praised’ (more or less like ‘Benedictus’ in Latin), and hence it can be some kind of honorific title, rather than a proper name.

3) Other Christian texts dating from between 640 and 670 depict the invaders as ‘Hagarian’, i.e., descendants of Abraham and his concubine Hagar, mother of Ishmael, and as allied of the Jews, refer to their negation of the divinity of Christ, and even mention a ‘Mahmet’ as an Ishmaelite preacher who taught his followers to worship the God of Abraham, as well as an Arab general’s appeal to the Byzantine emperor himself to embrace some Abrahamic monotheism.

4) The rest of contemporary (i.e., 7th century) Christian references to Arabic conquerors depict them as ‘atheist’ (‘godless’) or ‘pagans’, what is understandable taking into account that they were a hostile force, and make absolutely no reference (except those cryptic ones mentioned in the previous three points) to the invaders having something like a new religion, or being monotheists, or having a sacred book, or following religious practices, or whatever other indications of their being what later would be known as ‘Muslims’. Perhaps this is just a misrepresentation by part of the defeated, or perhaps they took as representative a portion of the ‘Saracene’ army that was still polytheists and have not been at that time ‘converted’ to Islam, or simply most of the ‘Muslims’ of the time didn’t follow the practices that were sanctified a century later.

5) Only by 730 (one whole century after the death of Muhammad), in a book On the Heresies written by the theologian John of Damascus, something closely related to the teachings of the Qur’an is commented in detail. The author, however, does not give the impression of those teachings being collected into a single book, but always refers to individual ‘writings’ that undoubtedly correspond to single suras of the Qur’an.

In the next section, we will see what the few standing contemporary Arabic sources say about the invaders themselves.

The Sources

In the previous section, we saw what Middle-East Christian texts from the 7th century told about the Arabian invaders that abruptly took those wealthy territories that during the previous centuries had been disputed between the Romans and the Persians (first, Palestina, Syria and Mesopotamia; a little later Egypt and Persia itself). In a nutshell, they identified the invader forces as guided by a ‘prophet’, though during the first decades of the invasion Christians referred to the Arabs’ faith as something vaguely close to Judaism, and only one hundred years after the supposed death of Muhammad there is some reference in those texts to the content of something similar to the Qur’an. Perhaps we might think that contemporary Arabic sources would be more explicit about the religious beliefs of those people, but this would prove to be a vain expectation, as we shall immediately see. Let’s briefly describe the most important pieces of evidence. The data are taken mostly from Spencer (2012) and Holland (2012).

1) Probably the oldest preserved reference that uses the Islamic calendar is a receipt of the exaction of sixty-five sheep from the Greco-Egyptian city of Herakleopolis, which is written both in Greek and in Arabic, and with the dates in the two corresponding calendars (22nd AH, 632 CE). According to the tradition, Arabs had started to count the years from the Hijra (the escape of Muhammad and his followers from Mecca to Medina in 610 CE) only five years before the date recorded in that document, in 627/28. Unfortunately, nothing on it refers to what the counting might mean, but it is clear that, being a date so close to the conventional starting year, the memory of the ‘inaugurating’ event wouldn’t have been lost or severely distorted, as compared, e.g., to the case of the Christian calendar, which started to be used more than five centuries after the birth of Jesus. Hence, this is a reason supporting the historicity of the Hijra, though of course not applicable to all of its traditional details.

2) Another almost contemporary text, recently discovered, is an inscription on stone, in the desert to the south of Palestine, mentioning that it was written: “at the time Umar died, in the year 24”. Umar was the second Caliph, and the traditional date of his assassination coincides with that of the inscription.

3) From about fifteen years later it dates another inscription, this time in a bath-house in the Syrian city of Gadara (close to the Lake of Galilee). Although the inscription is in Greek, it identifies Muawiya (the first Umayyad caliph) as “servant of God and leader of the protectors”, and gives the date “42 following the Arabs”. The inscription lacks any clear reference to Muslim religion, refers to the Arab rulers as ‘protectors’ (supposedly) of the Christian Byzantine community to which the baths belonged, and gives no religious interpretation of the year’s number; all this allows to cast some sceptical doubts about whether those Arabs were practicing something like orthodox Islam. But most surprising are the facts that the inscription does not contain any reference at all to Muhammad, and is preceded by a cross.

4) Another inscription, this time in Arabic, found in Karbala (Iraq), dates from 64 AH (683 CE), and, though in this case it starts by the traditional Muslim invocation “In the name of Allah the Merciful, the Compassionate”, later it refers to Allah as “the Lord of Gabriel, Michael and Asrafil” (three Biblical angels), again without any mention to Muhammad. Another curious fact about it is that it refers to three moments of praying (as the Qur’an itself states), not to the five that became the rule in the following century. An almost contemporary inscription found in Ta’if, near Mecca, makes also no reference at all to Muhammad. This scheme is all-pervasive in almost all official inscriptions in the Arab world dating from the first century of the Islamic era.

5) Equally surprising is the fact that the coins minted by the first caliphs, rarely include the word “Muhammad” (and when they do it, it isn’t clear whether it functions as the Prophet’s proper name, or in the sense of “let the Caliph be praised in the name of God”, because that “Muhammad” means “blessed” or “praised” in Arabic), but, contrarily to Islamic law, they represent a human figure (either the Caliph or –possibly– the Prophet)… which is carrying a cross! One coin from Muawiya’s time includes the same figure but with (for the first time) a tiny crescent topping the cross.

6) Probably, the first Islamic text beside the Qur’an is the inscription in the mosaics of Jerusalem’s Dome of the Rock, completed by 691 CE. It includes fragments of the Qur’an (though not in a completely literal way), and explicitly mentions Muhammad, but curiously most of its text is devoted to criticizing the Christian claim that Jesus is the son of God, and actually the portion of the text that is devoted to Jesus (and to praise his role as a messenger of God) is much bigger than the one devoted to the own Islam’s Prophet, of whom it only expresses the laconic claim that “Muhammad is the messenger of God”, which (as in the case of the coins) some scholars interpret not as a reference to the Arabian Prophet, but as a generic blessing to (whoever happens to be) the messenger of God, perhaps Jesus himself, or some other Biblical or post-Biblical prophet, or, more probably, to all of them.

After having devoted the first article of this series to present what Mid-Eastern Christian chroniclers contemporary of the Arab invasions wrote, it would be natural to expect that this second instalment would include the same about Arab chroniclers. The sad fact is those chronicles simply didn’t exist, at least as written works. The first Muslim historians wrote more than one century after Muhammad’s life, and even the books of those have not directly arrived to us, but only in quotes and mentions made by authors from at least many decades well into the second century of the Islamic Era. The Qur’an itself is the only Arabic literary source dating from the 7th century CE, and we will examine some of the philological research about it in our next article.

Hence, the truth is that all knowledge about the first century of Islam from ‘Islamic’ sources depends on the oral tradition. The first Arab historians made an art of the certification of the isnads, the chains of transmitters that supposedly were passing the hadith (a saying or a deed of the Prophet or of someone related to him), but obviously there were no absolutely reliable means by then of carrying out that certification without error, and, furthermore, occasion for corrupting or even inventing hadiths and isnads alike would abound in a time (more than one century) when the Islamic orthodoxy, institutions and nuclei of power were just taking shape. It is told that Bukhari, one of the first hadith collectors in the 9th century CE compiled about 300.000 such stories, of which he chose to publish only about 7.500 as valuable, but with only around one third that he himself considered “authentic”; so, less than one out of thousand.

There is one particularly compelling argument (Jansen, 2008) that serves to shed doubt on the credibility of most of the hadiths. It is the fact that in the first biography (Sira) of Muhammad, written by Ibn Ishaq in mid 8th century CE, dates are meticulously recorded. This fact apparently gave a high credibility to Ibn Ishaq’s narration, both under the eyes of subsequent Islamic historiographers and from the point of view of Western scholars. But there is a deep problem with Ibn Ishaq’s dates. The Islamic lunar calendar substituted a pre-Islamic Arabian, also lunar one, by 629 CE (still in Muhammad’s life), the main difference between both is that the pre-Islamic calendar included a ‘leap month’ every three years to keep the pace of the solar calendar (for twelve lunar months add only up to 354 days). Muhammad forbade the practice of including leap months, and hence the Islamic official calendar has a year which is about 11 days shorter than the solar year, which means that 34 Islamic years are equivalent to about 33 –Julian or Gregorian–solar years. But curiously, not a single event previous to 629 CE narrated by Ibn Ishaq takes place during a leap month! According to Jansen, the most sensible explanation of this is that the hadiths containing those events were invented in a time when people had just forgotten that leap months had existed at all.

The Qur’an

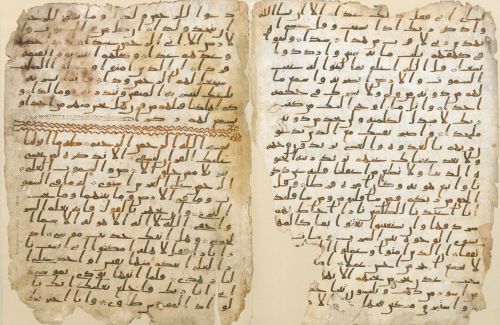

Here we shall explore some of the information contained in or directly connected to the Qur’an itself. As I explained in the previous article, the Holy Qur’an is the only important Arabic written document from the VIIth century. Even stone inscriptions in Arabic are not too earlier, the oldest ones (still not using the Arabic alphabet, but a form of Nabatean Aramaic alphabet) coming from the IVth century; the Arabic alphabet itself had to wait one or two more centuries still to start being developed, mostly in what today are Jordan and southern Syria, and mostly used in inscriptions which are undoubtedly Christian. As we shall see, the fact that Arabic script had not fully developed yet by the VIIth century causes lots of problems for the correct interpretation of the Qur’an and for the assessment of its origins.

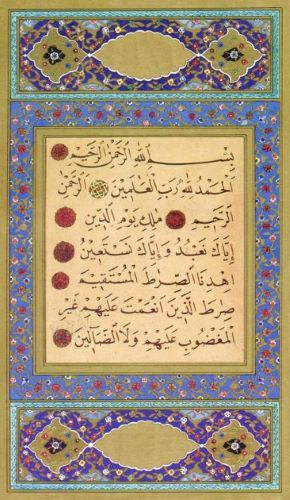

The Qur’an was not originally written as a whole book. Actually, according to Muslim tradition, at the beginning it was not written at all, but just orally recited (Qur’an means ‘recitation’) by Muhammad (or, first and foremost, by the archangel Gabriel to the Prophet) and by his disciples, and only later some of these started bothering to transcribe it so as to preserve its memory as acutely as possible. Muhammad’s recitations had no ‘logical’, ‘thematic’ order, but seemed to respond to particular facts or situations the Qur’an itself is profoundly obscure about. The traditional edition of the ‘book’ collects the single ‘revelations’ (verses, i.e., ayaht, or ‘signs’) into 114 ‘chapters’ that have a certain thematic unity (suras), but these ‘chapters’ are not themselves collected according to any chronological, thematic or otherwise systematic guidelines, but simply by its length: the longer suras at the beginning and the shorter ones at the end. Muslim tradition classifies the suras according to whether they have been ‘revealed’ before or after the hijra (622 CE), i.e., to whether they come from the time of Muhammad at Mecca or at Medina. This division between Meccan and Medinan suras was done either for stylistic reasons (the former tend to use shorter verses and employ a slightly different vocabulary –e.g., the name al-Rahman –the Merciful– for God), but also for exegetical reasons: according to the doctrine of ‘abrogation’, the revelations that came later in time can ‘abrogate’ (‘correct’ or ‘substitute’) the message of earlier ones, so that, in case of contradiction between two suras or verses, the Muslim exegetes could argue that one of them was revealed later, and so it is this one which has to be preferred as the interpretation of God’s will.

However, lacking almost any reliable evidence about the validity of the traditional account of the Qur’an’s history, contemporary scholarship has attempted to scrutinize the book in search of hints about its possible origin, influences and circumstances of its edition. This research has led to the proposal of several theories that, unfortunately, remain highly speculative due to lack of definite evidence. We shall present in the remaining of this entry and the next one the main facts these theories are based on.

1) Being the first (and the most) important work composed in Arabic, it is understandable that whoever the author of the Qur’an might be, he (it’s difficult to imagine that it was the work of a woman) was proud of his use of the Arabic language. So the Qur’an mentions many times that it is transmitted ‘in clear, pure Arabic’… in fact, it does it too many times. It is strange this insistence in making it explicit the language in which the work is written, but it is still more strange if we think that the text was originally an oral recitation. “Of course I’m listening that you are speaking to me in Arabic; why do you insist on that obvious point so often?”, one might think. As Spencer puts it, “when the Qur’an repeatedly insists that it is written in Arabic, it is not unreasonable to conclude that someone, somewhere was saying that it wasn’t in Arabic at all. A point needs emphasis only when it is controverted… The Qur’an thus may insist so repeatedly on its Arabic essence because that was precisely the aspect of it that others were challenging”. We shall come back to this point in the next entry.

2) Though obviously, the Qur’an is in Arabic, it is not so obvious that it is in “clear Arabic”, as it also repeatedly asserts. As philologist Gerd Puin put it, “if you look at (the Qur’an), you will notice that every fifth sentence or so simply doesn’t make sense… The fact is that a fifth of the Koranic text is just incomprehensible” (quoted in Spencer, 2012). This is due to multiple kinds of language problems, from terms that only appear in the Qur’an and so it’s difficult to know what they mean, to semantic or syntactic inconsistencies, ellipses, anacolutha, etc. This makes the translation of the Qur’an especially problematic, and it is perhaps one of the reasons why Muslims reject so fiercely to translate their holy book. Muslims exegetes have been deeply conscious of this problem from the beginning, for their work has precisely been that of trying to explain what the Qur’an means; in fact, no Muslim can directly understand most of the Qur’an save thanks to that exegetical work. Of course, the exegesis of sacred texts is not exclusive of Islam, but in the case of the Bible, for example, exegesis tries to explore the ‘occult meaning’ of the text (say, the prophetic or moral message), that usually can be thought to be very different from its ‘apparent meaning’… In the case of the Qur’an, the problem is, instead, that there is often no such a thing as an ‘apparent meaning’. This does not mean, of course, that those difficult-to-understand texts lack strong rhetorical power or poetical sublimity.

3) Another frustrating (especially for Western readers) feature of the Qur’an is that it contains basically no reference at all to the social, historical, or political reality in which it was conceived. Most references to specific and identifiable characters are indeed to Biblical names, from Adam to Jesus; Moses, in particular, is the most cited person in the whole Qur’an (probably as a paradigm of the mix Prophet/Stateman that Muhammad was claiming for himself). Instead, Muhammad is cited by that name only a fistful of times, though in many occasions the text refers to ‘the Messenger’ (rasul) as the one to which the recitation is addressed, or the person some of whose actions the saying is about. As we saw in previous entries, muhammad means ‘blessed’, so it is not absolutely clear that the word is used as a proper name when it appears. This lack of references to contemporary events that might be tested by independent sources makes the dating of the suras practically impossible, as well as the determination of the place or places of the composition. The fortunate finding of a Syriac text entitled Alexander Legend in the late XIXth century has provided one of the few (if not the only) possibilities of dating one particular sura. There is a close parallel between parts of that text and sura 18:83-102 (sura of The Cave), which seems to be a summary of the ‘prophesies’ the Syriac book attributes to Alexander the Great (the Qur’an –but not the Legend– refers to the Greek king as ‘Dhu l-Qarnyan’, i.e., ‘the Two-Horned’, exactly as Alexander was represented in some old coins, bearing two ram horns, probably indicating the power of the sun). The Alexander Legend was most likely composed in northern Syria to commemorate the victory of Byzantine emperor Heraclius over the Persians and the recovery of Jerusalem, around 630 CE. It is an apocalyptic book that became very popular in the following decades, and that mixes some deeds of Alexander with some Christian prophesies in order to show that the clash of the Roman and Persian empires, the raids of northern tribes on the Middle East, and other ‘signs’ were announcing the end of the times. The Qur’an summary shares this apocalyptic vision, though of course avoiding a Christian interpretation. It cannot be doubted that the Qur’an version derives (most probably directly, because of the close parallel even in their phrasing) from the Syrian text. This does not make it impossible that the sura of The Cave had been composed by Muhammad in his last years (remember that he is assumed to have died by 632 CE), though two years seems too little time for the Alexander Legend having circulated from Edessa (now in Southern Turkey) to Mecca in so a detailed way as to allow for the existing parallels with the Qur’an text. Other possibilities are, for example, that Muhammad had lived longer (remember that the Doctrina Jacobi mentioned around 635-640 a living ‘prophet’ commanding the Arab invaders of Palestine), or that The Cave had been composed much later by someone else. Whatever the real explanation, the fact is that the chronology of the Alexander Legend is incompatible with the ascription of the sura to the Meccan period (as the Muslim exegesis does), a period that had supposedly ended by 622, too long before the taking of Jerusalem by the Byzantines.

Conclusion

We shall conclude, indicating some further interesting facts about the Qur’an.

4) By Muhammad’s time, the Arabic alphabet contained no marks for vowels; furthermore, some groups of consonants were written with exactly the same character (e.g., the symbols for sounds b, t, th and n). One century later or so, this problem started to solve thanks to the use of diacritical points, but in the meantime this must have entailed that the first written copies of the suras would probably have been relatively difficult to interpret by their readers (those documents must have served most likely more as an assistance for remembering the text by someone that knew it by heart, than as a useful document for those who didn’t); but as knowledge of the text started to expand geographically and chronologically, more and more people would have had to rely on the written format, as preoccupation about the ‘correct’ edition of the Qur’an by part of the authorities from the middle of the VIIth century onwards demonstrates. This means that occasions for some misreading can have been abundant at least during one century or so. The Islamic tradition recognises this fact in several stories, perhaps legendary but with some historical background. For example, under the reign of Uthman, the third caliph (644-656 CE, 22-35 AH), tradition asserts that a committee was formed to establish a version of the Qur’an as authoritative; several copies of that version were sent to the corners of the new Arab empire, and all the other existing written copies of Muhammad’s recitations were destroyed. This means, obviously, that divergent versions of the Qur’an or of its suras must have existed even by that early time, though the tradition claims that the differences with the orthodox text only amounted to matters of the use of one or other Arabic dialect (the Quraysh dialect of the Meccan region was obviously privileged, as assumed to be the one in which Muhammad himself made the recitations). As a matter of fact, Islamic orthodoxy still accepts today as legitimate ‘the Seven Readings’, i.e., seven various ways of pronouncing the Qur’an text according to dialectal divergences (what makes it suspect that the versions destroyed by Uthman were different from the official one only by mere dialectal reasons). At least two existing Qur’ans are traditionally claimed to be some of the Uthman’s copies: the Topkapi (Istanbul) and the Samarkand (Tashkent, Uzbekistan) manuscripts, but a calligraphic study shows that they cannot date from before the end of the VII century CE. Be that as it may, the truth is that there is no documental proof (only the tradition) of the Qur’an having been codified by Uthman in its present form, since the oldest known manuscripts (with the possible exception of some of the parchments discovered in the Yemeni mosque of Sana’a forty years ago, and still demanding a comprehensive philological and palaeographic study) date from between half a century or one century after Uthman’s death, and what is perhaps more important, the first historical references to the Qur’an as a complete and definitive collection of suras, date also from that time. Remember what we saw in the first entry, that even around 730 CE contemporaries referred to the Islamic sacred texts (the suras) in an individual way, not as forming a single book.

5) The near incomprehensibility of many parts of the Qur’an in a direct reading (, i.e., without the help of an exegesis; see point 2 of the previous section), and the possibility that some letters, words or phrases have been misread by the first Muslims, has stimulated a fistful of ‘alternative’ or ‘revisionist’ theories about the origin and compilation of the sacred book. The most famous of those theories has been the one proposed by the German author Christoph Luxenberg (again, a pseudonym). The revolutionary method employed by him consists in trying first to give sense to the obscure sentences by changing the diacritical points (transforming a word in another, mostly by keeping the consonants and substituting the vowels, but also allowing for some change in the consonants taking into account the similarities between some of them in pre-classical Arabic, as we have just seen). If all admissible combinations still make no sense, Luxenberg considers whether the word might be not from Arabic, but from Syro-Aramaic (which, after all, was at the time the koiné used in the Middle East). Surprisingly, some of the obscure passages seem to make much more sense thanks to this hypothesis. Actually, the very same word Qur’an does come from the Aramaic word queryana (‘lectionary’ or ‘missal’, i.e., a Christian prayer book), and is originally more appropriate for a collection of texts prepared for being read (‘recited’) at religious ceremonies than for a collection of oral speeches (though, of course, it has taken this latter meaning in classical Arabic). Luxenberg tries to show that many of the suras, or parts of them, are probably translations-cum-modification of (non-orthodox, perhaps monophysite) Christian religious texts used by some of the numerous Christian communities existing by the VIth and VIIth centuries in what today are Palestine, Jordan, Syria and Arabia. For example, he argues that sura 97 (‘the Destiny’ o ‘the Night of Power’) would really be an allusion to the festivity of Christmas. But most famous due to its reception in the media has been the hypothesis that the huris-of-wide-eyes mentioned several times in the Koran as the young females waiting in the Paradise for the martyrs of the jihad, were, in fact, a transliteration of the Aramaic word for brunches of white grapes, which is an interpretation that fits better with the rest of the text in which the word appears. Luxenberg’s claims, however, have been received with scepticism even by many Western Qur’an scholars, for lacking philological systematicity and historical references to the cultural and political contexts of the time. They, nevertheless, are to be examined one by one according to the evidence. It would not come as a surprise, however, to experts in the history of culture, that some or many of the textual content of the Qur’an were by some direct or indirect way derived from the Christian or Judean milieu pre-existing in many of the human communities of VIth century Arabia and surroundings, exactly as some of the narrative content of many suras is about Biblical characters, as we saw in the past entry. Unfortunately, only the discovery of more manuscripts coming from that time could serve to scientifically settle this fundamental question.

Originally published by Mapping Ignorance, 05.13.2013, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.