Bleach occupies a liminal space between reassurance and risk, embodying the promises and anxieties of modern chemical life.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Bleaching as Practice, Symbol, and Technology

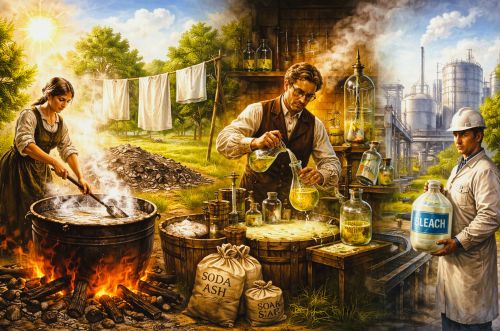

The whitening of textiles is one of the oldest material practices through which societies have expressed ideas about cleanliness, order, and refinement. Long before the development of modern chemistry, the visual transformation of cloth carried cultural weight, marking distinctions between ritual purity and impurity, labor and leisure, wealth and scarcity. In ancient societies where textiles were costly and labor-intensive to produce, whiteness signified not only cleanliness but control over material processes and time itself. Bleaching was therefore never a purely technical act. It was embedded in social structures, environmental knowledge, and symbolic systems that shaped how people understood both cloth and the bodies that wore it.1

Early bleaching methods relied on empirical observation rather than theoretical explanation. In ancient Egypt, linen was whitened through repeated washing, treatment with alkaline solutions derived from plant ashes, and prolonged exposure to sunlight, practices grounded in the predictable effects of heat, water, and alkalinity on organic fibers. These techniques required patience and space, often involving extended outdoor drying that tied textile production to climate and seasonal rhythms. Similar methods persisted across the Mediterranean and into medieval Europe, where bleaching fields and ash-based lyes remained central to textile preparation. Such continuity underscores that effective bleaching existed long before its chemical mechanisms were understood.2

The gradual shift from artisanal bleaching to chemical bleaching did not occur through sudden rupture but through the slow accumulation of experimental knowledge in the early modern period. As natural philosophers began to isolate and classify substances such as alkalis, acids, and gases, traditional practices acquired new explanatory frameworks. Bleaching, once understood as the result of sun, air, and washing, increasingly became associated with specific reactive agents capable of altering color at the material level. This conceptual transition prepared the ground for the dramatic innovations of the late eighteenth century, when laboratory chemistry began to intersect directly with industrial production.3

The emergence of chlorine-based bleaching in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries marked a decisive transformation in both scale and speed. Discoveries by chemists such as Carl Wilhelm Scheele and Claude Louis Berthollet converted bleaching from a seasonal, labor-intensive process into a controlled chemical operation. Subsequent industrial adaptations, including solid bleaching powders and later liquid hypochlorite solutions, detached bleaching from environmental dependence and placed it firmly within the realm of manufactured chemistry. By the early twentieth century, bleach had moved from workshops and factories into domestic spaces, becoming a routine household substance associated with hygiene, sanitation, and modern living.4

Tracing the history of bleach therefore reveals more than the evolution of a chemical compound. It exposes a broader transformation in how societies understood cleanliness, labor, and the relationship between nature and technology. From sunlit fields and wood ashes to patented powders and branded bottles, bleach stands as a material record of humanity’s shifting capacity to manipulate matter in pursuit of order and purity. Its history offers a window into the convergence of cultural values and chemical knowledge that continues to shape everyday life.5

Ancient and Pre-Industrial Bleaching Techniques

The earliest bleaching practices emerged from sustained interaction with environmental forces rather than from formal chemical theory. In ancient Egypt, linen production relied heavily on repeated washing, alkaline treatments derived from wood ash, and prolonged exposure to sunlight, a process that exploited the combined effects of heat, moisture, and naturally occurring alkalis on plant fibers.6 Linen’s central role in Egyptian ritual and daily life intensified the importance of these techniques, since whiteness was closely associated with purity, order, and proper social presentation. The labor required for such bleaching tied textile production to seasonal rhythms and available space, embedding chemical transformation within environmental constraint.

The alkaline solutions used in early bleaching were not accidental discoveries but products of empirical refinement. Wood ashes mixed with water produced lye rich in potassium carbonate, a substance capable of breaking down organic residues and lightening fibers through repeated application.7 Although ancient practitioners lacked a molecular understanding of alkalinity, they clearly recognized its practical effects. This knowledge circulated widely across cultures, appearing in Greco-Roman laundering practices and persisting through the medieval period in both urban and rural contexts. The continuity of ash-based bleaching underscores the durability of techniques grounded in observable, repeatable outcomes rather than abstract explanation.

Sunlight itself functioned as an active bleaching agent in pre-industrial societies. Extended exposure to ultraviolet radiation gradually broke down chromophores in organic stains, a process exploited through open-air bleaching fields common in parts of Europe by the late Middle Ages.8 These fields required significant land and time, reinforcing bleaching as a slow, collective enterprise rather than an isolated household task. The reliance on sun and air also meant that bleaching was subject to weather variability, further limiting scalability and consistency. Such constraints would later become key drivers for chemical alternatives.

Medieval and early modern Europe inherited and systematized these ancient practices without fundamentally altering their material basis. Laundering manuals and household guides described sequences of washing, soaking, and drying that combined alkaline solutions with mechanical agitation and sun exposure.9 While artisanal dyers and fullers refined their methods for specific fibers, bleaching remained largely dependent on repetition and patience. Importantly, these texts reveal a practical understanding of cause and effect without recourse to theoretical chemistry, demonstrating that effective material knowledge could exist independently of scientific abstraction.

By the seventeenth century, the limitations of traditional bleaching became increasingly apparent as textile production expanded. Growing demand for lighter fabrics exposed the inefficiencies of sun- and ash-based methods, particularly their reliance on space, time, and favorable climate.10 These pressures did not immediately produce chemical bleaching but instead sharpened interest in understanding why certain substances whitened cloth. Pre-industrial bleaching techniques thus represent both the culmination of ancient empirical knowledge and the threshold beyond which new chemical explanations became necessary, setting the stage for the transformations of the eighteenth century.11

The Chemical Context Before Chlorine

By the seventeenth century, bleaching practices stood at the intersection of craft knowledge and emerging chemical inquiry. Artisans understood that alkalis, repeated washing, and exposure to air altered textiles in predictable ways, but the reasons for those changes remained conceptually opaque. Natural philosophers increasingly turned their attention to substances involved in everyday processes, treating lyes, acids, and mineral salts as objects of systematic investigation rather than merely household materials.12 This shift did not immediately transform bleaching itself, but it altered how such practices were discussed, recorded, and evaluated.

Central to this changing context was the gradual clarification of alkalis and acids as distinct classes of substances. Early modern chemists investigated potash and soda ash, recognizing their shared properties while debating their origins and relative strengths.13 These studies drew directly from practices already embedded in laundering and textile preparation, revealing a reciprocal relationship between domestic labor and experimental chemistry. Bleaching thus served as a practical reference point through which chemical thinkers tested broader theories of matter, even when terminology and explanatory models remained unstable.

The study of air and gases further expanded the chemical landscape in which bleaching was understood. Experiments on combustion, respiration, and fermentation challenged older Aristotelian notions of elements and prepared the ground for pneumatic chemistry.14 Although bleaching still relied on sun and alkali, the growing recognition that invisible substances in air could actively alter materials encouraged speculation about faster, more controllable methods. Such ideas circulated well before chlorine’s isolation, shaping expectations that chemical agents might replicate or surpass the effects of long exposure to light and atmosphere.

These developments unfolded within theoretical frameworks that now appear deeply flawed, particularly phlogiston theory. Yet phlogiston chemistry provided a coherent language for discussing processes of color change, oxidation, and purification.15 Bleaching was interpreted as a form of dephlogistication, a removal of an unwanted principle from cloth, rather than as a surface-level cleaning. This conceptualization did not solve the practical limitations of pre-industrial bleaching, but it created an intellectual environment in which the discovery of new reactive substances could be immediately recognized as transformative. When chlorine entered this landscape in the late eighteenth century, it did so not as an isolated marvel but as the culmination of decades of chemical reorientation.16

Carl Wilhelm Scheele and the Discovery of Chlorine (1774)

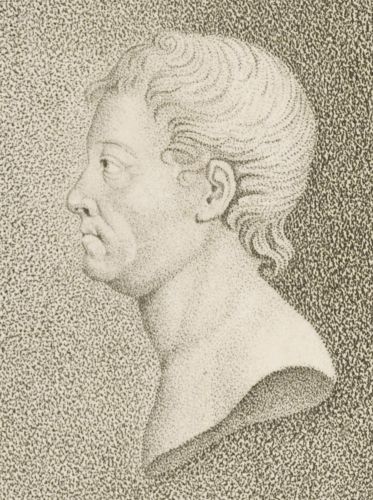

The decisive shift toward chemical bleaching became possible only after the isolation of a substance capable of acting rapidly and predictably on color. This moment arrived in 1774, when the Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele identified a previously unknown greenish-yellow gas while experimenting with pyrolusite (manganese dioxide) and muriatic acid.17 Scheele observed that the gas possessed a suffocating odor and a remarkable ability to alter organic materials, including plant matter and pigments. Although he did not yet recognize it as an element, his careful description of its properties marked the first clear identification of what would later be named chlorine.

Scheele worked within the conceptual framework of phlogiston theory, which shaped how he interpreted his findings. He described the gas as “dephlogisticated muriatic acid,” believing it to be muriatic acid stripped of phlogiston rather than a distinct substance.18 This interpretation was consistent with contemporary chemical language and does not diminish the precision of his experimental work. Scheele systematically recorded the gas’s reactivity with metals, its bleaching effect on flowers, and its toxicity when inhaled, demonstrating an unusually empirical approach even by late eighteenth-century standards.

The bleaching implications of Scheele’s discovery were not immediately pursued, but his observations laid essential groundwork. By showing that color could be altered rapidly through chemical interaction rather than prolonged exposure to sun and air, Scheele implicitly challenged the temporal and spatial constraints of traditional bleaching practices.19 His work circulated widely through chemical correspondence and publications, ensuring that other chemists recognized the gas as a substance of exceptional reactivity. The discovery thus entered a scientific community already primed to seek faster and more controllable alternatives to established textile methods.

Scheele himself did not attempt to industrialize or commercialize the gas, nor did he frame his discovery in economic terms. Its significance lay instead in expanding the known repertoire of chemical agents capable of transforming organic matter. Once detached from phlogiston theory and reinterpreted through emerging chemical nomenclature, chlorine would become a central tool in industrial chemistry.20 Scheele’s contribution therefore stands as a pivotal moment in the history of bleaching, bridging artisanal practice and industrial chemistry through experimental discovery rather than deliberate technological design.

Claude Louis Berthollet and Chemical Bleaching (1785)

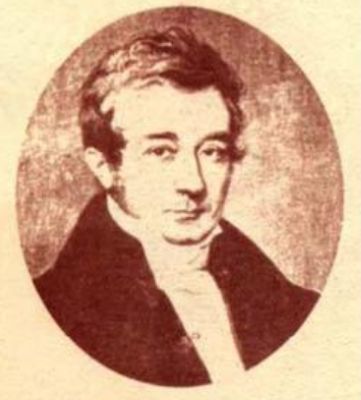

The practical transformation of chlorine from laboratory curiosity to industrial agent occurred through the work of the French chemist Claude Louis Berthollet. In the mid-1780s, Berthollet recognized that substances derived from chlorine could whiten textiles rapidly and with far greater consistency than traditional sun-based methods.21 Working within the institutional context of French state science, he explored the interaction between chlorine compounds and organic dyes, observing that color removal resulted from chemical alteration rather than surface cleansing. This insight marked a decisive departure from earlier bleaching practices rooted in time and exposure.

Berthollet’s experiments led to the development of a liquid bleaching solution produced by passing chlorine into an alkaline medium, yielding what became known as “Javel water,” a solution containing potassium hypochlorite.22 The process allowed chlorine’s reactivity to be harnessed in a form that signals safer and more controllable than the gas itself, though still hazardous by modern standards. Crucially, Berthollet framed this innovation within contemporary chemical theory, interpreting bleaching as a reaction that destroyed color through chemical affinity. His work thus provided both a practical method and a conceptual explanation that appealed to industrial and scientific audiences alike.

The adoption of chemical bleaching occurred against the backdrop of expanding textile production and political transformation in France. Berthollet’s position within the scientific institutions of the French state facilitated the translation of laboratory findings into manufacturing practice.23 Chemical bleaching offered clear economic advantages by shortening production cycles and reducing dependence on large bleaching fields. Its introduction therefore aligned closely with broader efforts to rationalize industry through science, a hallmark of late eighteenth-century reformist thought.

Despite its promise, chemical bleaching also revealed significant challenges. Early hypochlorite solutions were unstable and corrosive, requiring careful handling and precise preparation to avoid damaging fabrics or endangering workers.24 Berthollet himself acknowledged these limitations, emphasizing the need for technical expertise and regulation. Nevertheless, his work established the principle that bleaching could be achieved through controlled chemical reactions rather than environmental exposure. This conceptual shift paved the way for subsequent innovations that would further stabilize and standardize bleaching agents, transforming them into durable components of industrial chemistry.25

Industrialization and Charles Tennant’s Bleaching Powder (1799)

The transition from liquid chemical bleaching to a stable, transportable product was achieved at the end of the eighteenth century through the work of the Scottish industrial chemist Charles Tennant. While Berthollet’s hypochlorite solutions demonstrated chlorine’s bleaching power, their instability and hazardous handling limited widespread adoption. Tennant addressed these constraints by developing a solid bleaching agent produced by passing chlorine over slaked lime, yielding what became known as bleaching powder, primarily composed of calcium hypochlorite.26 This innovation transformed chemical bleaching from a localized technique into a scalable industrial process.

Tennant’s bleaching powder offered several decisive advantages over earlier methods. As a solid, it could be stored, transported, and measured with far greater ease than liquid solutions or chlorine gas.27 Textile manufacturers could now apply chemical bleaching without maintaining specialized chemical apparatus on site, reducing both cost and risk. The powder’s relative stability also allowed bleaching to be integrated more smoothly into existing production workflows, accelerating output and diminishing reliance on large bleaching fields. These practical benefits quickly made Tennant’s product indispensable to the British textile industry.

In 1799, Tennant secured a patent for his bleaching powder, signaling the growing importance of intellectual property in industrial chemistry.28 The patent formalized the relationship between chemical innovation and commercial enterprise, embedding bleaching technology within emerging legal and economic structures. Tennant’s St. Rollox chemical works near Glasgow became one of the largest chemical manufacturing operations of its time, illustrating how chemical processes could underpin large-scale industrial growth. Bleaching powder thus exemplified the fusion of scientific knowledge, capital investment, and industrial organization characteristic of the Industrial Revolution.

Despite its success, bleaching powder was not without drawbacks. Its production released chlorine fumes, and improper handling could damage textiles or cause injury, prompting ongoing efforts to refine formulation and application.29 Nevertheless, Tennant’s innovation decisively altered the geography and tempo of bleaching, detaching it from climate and land availability. By rendering chemical bleaching portable and commercially viable, bleaching powder established the model through which later hypochlorite-based products would enter both industrial and domestic use, marking a critical stage in the modernization of cleanliness.30

From Textile Bleach to Domestic Chemical: Sodium Hypochlorite

The transition from industrial bleaching agents to household chemical products unfolded gradually during the nineteenth century as chemical knowledge, public health priorities, and manufacturing capacity converged. While calcium hypochlorite dominated large-scale textile bleaching, chemists continued to experiment with chlorine solutions better suited to controlled dilution and repeated use. Sodium hypochlorite emerged from this context as a liquid bleaching and disinfecting agent whose effectiveness could be adjusted by concentration, making it adaptable to environments beyond the factory floor.31 Its development marked an important step toward integrating chemical bleaching into everyday domestic and institutional life.

One of the earliest systematic applications of sodium hypochlorite occurred not in laundering but in sanitation and medicine. In the 1820s, the French chemist Antoine-Germain Labarraque demonstrated that dilute hypochlorite solutions could neutralize putrefaction and suppress foul odors in hospitals, morgues, and slaughterhouses.32 These solutions, later known as Labarraque’s liquids, were valued for their deodorizing and disinfecting properties rather than for fabric whitening alone. Their success linked chlorine chemistry directly to emerging concerns about public hygiene, disease prevention, and urban cleanliness, expanding bleach’s conceptual role beyond textiles.

Throughout the nineteenth century, sodium hypochlorite remained primarily an institutional substance, used in hospitals, municipal sanitation, and water treatment. Advances in chemical manufacturing improved the stability and consistency of hypochlorite solutions, while growing acceptance of contagion theories encouraged their use as preventative tools.33 Bleach increasingly became associated with safety and control in environments perceived as vulnerable to decay or infection. This association laid the groundwork for its later entry into the household, where similar anxieties about cleanliness and health shaped consumer demand.

The domestication of liquid bleach accelerated in the early twentieth century, particularly in the United States. Industrial producers recognized that sodium hypochlorite solutions could be packaged, standardized, and marketed for home use, provided their concentration was carefully regulated.34 In 1913, the Clorox company began commercial production of liquid bleach intended for household laundering and cleaning, transforming a chemical reagent into a branded consumer product. This shift depended not only on chemistry but on trust, labeling, and education, as consumers had to be persuaded that a powerful chemical could be used safely in domestic spaces.

Household bleach reshaped domestic labor by reducing the time and effort required to whiten fabrics and disinfect surfaces. Tasks that once demanded prolonged soaking, exposure to sunlight, or repeated washing could now be completed quickly and indoors.35 This transformation intersected with broader changes in gendered labor, urban living, and expectations of cleanliness. Bleach became embedded in routines that defined modern domestic order, reinforcing ideals of visual whiteness and hygienic control as markers of responsible household management.

By the early twentieth century, sodium hypochlorite had come to embody a new relationship between chemistry and daily life. No longer confined to workshops, hospitals, or municipal systems, bleach circulated as a familiar yet potent substance within the home. Its success reflected decades of chemical refinement and cultural adaptation, as well as a growing willingness to entrust complex chemical processes to ordinary users. The rise of liquid bleach thus completed the transformation of bleaching from an environmental practice into a standardized chemical technology, firmly rooted in the rhythms of modern domestic life.36

Bleach, Hygiene, and Modernity

By the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, bleach had become inseparable from broader transformations in how societies understood hygiene and risk. Industrialization and urbanization concentrated populations in ways that made dirt, waste, and disease newly visible and alarming. Chemical agents capable of rapidly neutralizing odors, stains, and organic matter acquired heightened significance within this context.37 Bleach, in particular, came to represent a form of cleanliness that was not merely cosmetic but preventative, aligned with emerging ideas about controlling invisible threats in modern environments.

The growing authority of germ theory reshaped the cultural meaning of bleach. As medical science increasingly linked disease to microorganisms rather than miasmas or moral failings, substances that could destroy organic matter gained new legitimacy.38 Hypochlorite solutions were valued not only for whitening fabrics but for their ability to disinfect surfaces, linens, and instruments in hospitals and public institutions. Bleach thus bridged older visual standards of cleanliness and newer bacteriological ones, reinforcing the idea that whiteness signaled safety even as its justification shifted from appearance to microbiology.

Municipal sanitation systems further expanded bleach’s role in modern life. Chlorine-based compounds were adopted for water treatment as cities sought to prevent outbreaks of cholera and typhoid through chemical disinfection.39 This use extended bleach’s reach beyond households and hospitals into shared infrastructures that defined modern citizenship. Clean water, like clean laundry, became a matter of public trust in chemical expertise, embedding chlorine chemistry into the daily lives of populations who rarely encountered the science behind it.

Within the home, bleach became a tool through which modern ideals of domestic order were enacted. Advertisements and instructional literature framed bleach as both powerful and manageable, emphasizing its effectiveness while reassuring users of its safety when properly diluted.40 These messages intersected with gendered expectations of household labor, positioning chemical cleanliness as a marker of competence and care. Bleach enabled new standards of whiteness and sterility that would have been difficult to achieve through earlier methods, subtly raising expectations for domestic hygiene.

At the same time, the normalization of bleach introduced new risks that were unevenly distributed. Accidental poisonings, chemical burns, and the release of chlorine gas through improper mixing highlighted the dangers inherent in domestic chemical use.41 These hazards prompted the gradual development of labeling requirements, safety guidelines, and public education campaigns. Modernity’s embrace of bleach thus entailed not only confidence in chemistry but ongoing negotiation over regulation, responsibility, and acceptable risk.

Bleach’s cultural power in the modern era ultimately rests on its dual identity as both mundane and formidable. It is an everyday substance capable of extraordinary effects, simultaneously trusted and feared. This tension reflects a broader condition of modern life, in which chemical technologies promise control over nature while demanding vigilance in their use.42 As a symbol of hygiene, bleach embodies the modern conviction that cleanliness can be engineered, standardized, and enforced, even as its continued potency reminds users that such control is never absolute.

Environmental and Health Considerations

As bleach became a routine feature of industrial, municipal, and domestic life, its environmental and health consequences became increasingly difficult to ignore. Chlorine-based compounds are highly reactive, a property that underlies their usefulness but also their potential harm. Exposure to concentrated bleach can cause chemical burns, respiratory irritation, and, in enclosed spaces, life-threatening release of chlorine gas when mixed improperly with acids or ammonia.43 These risks were recognized early, particularly in industrial settings, where workers faced prolonged exposure well before comprehensive safety standards were established.

Environmental concerns emerged more slowly, in part because chlorine compounds were initially celebrated for their ability to neutralize organic waste. As bleach entered waterways through industrial discharge and household use, its broader ecological effects became clearer. Chlorine reacts with organic matter in water to form chlorinated byproducts, some of which persist in the environment and accumulate in living organisms.44 These reactions complicated earlier assumptions that chemical disinfection was an unambiguous public good, forcing reconsideration of how cleanliness and environmental stewardship might conflict.

Public health authorities faced a delicate balance. Chlorine-based disinfection dramatically reduced waterborne disease, a benefit that outweighed long-term environmental risks in many policy calculations.45 Yet the recognition that chlorination produced unintended chemical residues led to the gradual refinement of treatment standards and monitoring practices. Rather than abandoning chlorine, regulatory bodies sought to control dosage, exposure time, and byproduct formation, reflecting a broader modern tendency to manage risk rather than eliminate technology outright.

Within the household, the normalization of bleach introduced a different set of concerns. Consumer familiarity sometimes encouraged misuse, including overconcentration or unsafe mixing, which increased the likelihood of injury.46 Educational campaigns and standardized labeling emerged as responses to these dangers, translating chemical knowledge into practical guidance for non-specialists. The need for such mediation underscores the paradox of modern chemical life: substances powerful enough to reshape environments must be rendered legible and manageable to ordinary users.

Environmental and health debates surrounding bleach continue to reflect this tension between benefit and cost. Chlorine-based compounds remain indispensable in sanitation and emergency disinfection, even as alternative technologies and greener chemicals are explored.47 The history of bleach thus illustrates a recurring pattern in modern chemistry, where solutions to one set of problems generate new challenges that must be addressed through regulation, adaptation, and ongoing scientific assessment. Cleanliness achieved through chemistry has never been free of consequence, but its negotiated risks reveal how societies continually recalibrate their relationship with powerful materials.

Conclusion: Bleach as a Chemical and Cultural Artifact

The long history of bleach reveals a material practice shaped as much by culture and labor as by chemistry. From ancient sun-bleached linens to hypochlorite solutions engineered in laboratories, bleaching evolved through cumulative adjustments rather than sudden revolutions. What changed most dramatically over time was not the desire for whiteness itself, but the means by which it could be achieved. Early reliance on sun, air, and alkali embedded bleaching within environmental rhythms, whereas chemical bleaching detached the process from climate and season, transforming it into a controllable technological act.48 This shift altered not only production methods but expectations of speed, uniformity, and reliability.

Bleach’s rise as a chemical agent also illustrates how scientific explanation reshaped everyday experience. As chemical theory advanced, whitening ceased to be understood merely as the gradual fading of stains and became instead a reaction that altered matter at a fundamental level. The recognition that chlorine-based compounds destroyed color through chemical interaction rather than surface cleansing redefined what cleanliness meant in practical terms.49 Whiteness increasingly signified not just visual purity but chemical intervention, reinforcing modern associations between cleanliness, control, and scientific authority.

At the same time, bleach’s history complicates narratives of progress. The same properties that made hypochlorite compounds indispensable for sanitation and public health also introduced new hazards, requiring education, regulation, and constant reassessment. The normalization of bleach in homes, hospitals, and infrastructure depended on trust in chemical expertise and institutional oversight, a trust that has never been absolute.50 Bleach thus occupies a liminal space between reassurance and risk, embodying the promises and anxieties of modern chemical life.

Seen in this light, bleach functions as a cultural artifact as much as a chemical one. Its journey from sunlit fields to factory vats and household bottles reflects broader transformations in how societies organize labor, manage health, and relate to nature. Bleach endures not because it is benign, but because it has proven adaptable to shifting standards of safety, efficiency, and meaning. Its history reminds us that even the most ordinary substances carry layered pasts, shaped by the interplay of environment, knowledge, and power that defines technological modernity.51

Appendix

Footnotes

- Virginia Smith, Clean: A History of Personal Hygiene and Purity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).

- Ian Shaw, ed., The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000).

- Robert J. Forbes, Studies in Ancient Technology, vol. 4 (Leiden: Brill, 1965).

- William H. Brock, The Fontana History of Chemistry (London: Fontana Press, 1992).

- Ruth Schwartz Cowan, More Work for Mother: The Ironies of Household Technology from the Open Hearth to the Microwave (New York: Basic Books, 1983).

- Shaw, ed., The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt.

- Forbes, Studies in Ancient Technology, vol. 4.

- John Munro, “Textiles, Towns, and Trade,” in The Cambridge History of Medieval Europe, vol. 2 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

- Eleanora Carus-Wilson, “The Woollen Industry,” The Economic History Review 2, no. 2 (1950).

- Giorgio Riello, Cotton: The Fabric that Made the Modern World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013).

- Brock, The Fontana History of Chemistry.

- Brock, The Fontana History of Chemistry.

- Forbes, Studies in Ancient Technology, vol. 4.

- Steven Shapin, The Scientific Revolution (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996).

- Ursula Klein and Wolfgang Lefèvre, Materials in Eighteenth-Century Science (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007).

- Maurice Crosland, Historical Studies in the Language of Chemistry (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1962).

- Carl Wilhelm Scheele, “On Manganese and Its Properties,” 1774, in Chemical Essays, trans. Thomas Beddoes (London, 1786).

- Crosland, Historical Studies in the Language of Chemistry.

- Brock, The Fontana History of Chemistry.

- Klein and Lefèvre, Materials in Eighteenth-Century Science.

- Crosland, Historical Studies in the Language of Chemistry.

- Claude Louis Berthollet, “le pharmacien Curaudau et l’identification du chlore.” Revue d’Histoire de la Pharmacie (1955).

- Brock, The Fontana History of Chemistry.

- Klein and Lefèvre, Materials in Eighteenth-Century Science.

- Christine MacLeod, Heroes of Invention: Technology, Liberalism and British Identity, 1750–1914 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

- Brock, The Fontana History of Chemistry.

- MacLeod, Heroes of Invention.

- H. W. Dickinson, A Short History of the Steam Engine (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1939).

- Klein and Lefèvre, Materials in Eighteenth-Century Science.

- Geoffrey Tweedale, At the Sign of the Plough: 275 Years of Allen & Hanburys and the British Pharmaceutical Industry (London: John Murray, 1990).

- Brock, The Fontana History of Chemistry.

- Antoine-Germain Labarraque, Sur l’emploi des chlorures d’oxyde de sodium et de chaux (Paris, 1825).

- Christopher Hamlin, Public Health and Social Justice in the Age of Chadwick (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

- Smith, Clean.

- Cowan, More Work for Mother.

- Thomas P. Hughes, American Genesis: A Century of Invention and Technological Enthusiasm, 1870–1970 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989).

- Hamlin, Public Health and Social Justice in the Age of Chadwick.

- Bruno Latour, The Pasteurization of France (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988).

- David S. Barnes, The Great Stink of Paris and the Nineteenth-Century Struggle against Filth and Germs (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006).

- Smith, Clean.

- Gerald Markowitz and David Rosner, Deceit and Denial: The Deadly Politics of Industrial Pollution (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987).

- Hughes, American Genesis.

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, Toxicological Profile for Chlorine (Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010).

- World Health Organization, Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality, 4th ed. (Geneva: WHO Press, 2017).

- Hamlin, Public Health and Social Justice in the Age of Chadwick.

- Markowitz and Rosner, Deceit and Denial.

- Barnes, The Great Stink of Paris and the Nineteenth-Century Struggle against Filth and Germs.

- Brock, The Fontana History of Chemistry.

- Klein and Lefèvre, Materials in Eighteenth-Century Science.

- Hamlin, Public Health and Social Justice in the Age of Chadwick.

- Hughes, American Genesis.

Bibliography

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Toxicological Profile for Chlorine. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010.

- Barnes, David S. The Great Stink of Paris and the Nineteenth-Century Struggle against Filth and Germs. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006.

- Berthollet, Claude Louis. “le pharmacien Curaudau et l’identification du chlore.” Revue d’Histoire de la Pharmacie (1955).

- Brock, William H. The Fontana History of Chemistry. London: Fontana Press, 1992.

- Carus-Wilson, Eleanora. “The Woollen Industry.” The Economic History Review 2, no. 2 (1950): 140–155.

- Cowan, Ruth Schwartz. More Work for Mother: The Ironies of Household Technology from the Open Hearth to the Microwave. New York: Basic Books, 1983.

- Crosland, Maurice. Historical Studies in the Language of Chemistry. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1962.

- Dickinson, H. W. A Short History of the Steam Engine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1939.

- Forbes, Robert J. Studies in Ancient Technology. Vol. 4. Leiden: Brill, 1965.

- Hamlin, Christopher. Public Health and Social Justice in the Age of Chadwick. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Hughes, Thomas P. American Genesis: A Century of Invention and Technological Enthusiasm, 1870–1970. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989.

- Klein, Ursula, and Wolfgang Lefèvre. Materials in Eighteenth-Century Science. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007.

- Labarraque, Antoine-Germain. Sur l’emploi des chlorures d’oxyde de sodium et de chaux. Paris, 1825.

- Latour, Bruno. The Pasteurization of France. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988.

- MacLeod, Christine. Heroes of Invention: Technology, Liberalism and British Identity, 1750–1914. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Markowitz, Gerald, and David Rosner. Deceit and Denial: The Deadly Politics of Industrial Pollution. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987.

- Munro, John. “Textiles, Towns, and Trade.” In The Cambridge History of Medieval Europe, vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Riello, Giorgio. Cotton: The Fabric that Made the Modern World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Scheele, Carl Wilhelm. “On Manganese and Its Properties.” 1774. In Chemical Essays, translated by Thomas Beddoes. London, 1786.

- Shapin, Steven. The Scientific Revolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996.

- Shaw, Ian, ed. The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Smith, Virginia. Clean: A History of Personal Hygiene and Purity. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Tweedale, Geoffrey. At the Sign of the Plough: 275 Years of Allen & Hanburys and the British Pharmaceutical Industry. London: John Murray, 1990.

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality. 4th ed. Geneva: WHO Press, 2017.

Originally published by Brewminate, 12.17.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.