Many had often read and frequently referred to well-known theories.

By Dr. Catherine Kerrison

Professor of History

Villanova University

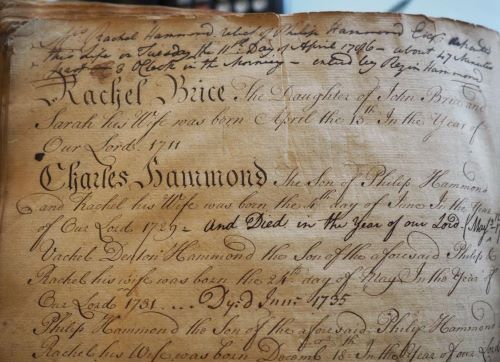

Though religious works were almost surely throughout the eighteenth century (as in the seventeenth) the most widely read books in the southern library, there is evidence that the three related areas of law, politics, and history were a strong second. The southern colonial bookshelf, though at times it had only ten volumes or less, was likely to carry—along with the Bible and New Testament and Book of Common Prayer or Westminster Confession and The Whole Duty of Man—one or more legal or historical titles. In Maryland in 1770, one poor man’s three books included Rapin’s History of England (volume 1). Other small collections included a layman’s legal manual, such as as The Compleat Lawyer or The Compleat Attorney or The Young Secretary’s Guide, or a volume or two of British or provincial statutes. On the shelf of any planter or merchant who was a local magistrate was at least one of the several convenient British compendiums for justices of the peace. One eighteenth-century southern colonial declared that, in his province of Virginia, John Mercer’s Abridgment of All the Public Acts of Assembly (1737) was to be found in libraries even more frequently than the Bible. Another Scottish-born Virginian declared that in his county a religious topic, if brought up in a large assembly, met with dead silence, “but bring any subject from Mercer’s abridgement and the youngest in Company will immediately tell you how far a grin is actionable.” A volume of political philosophy, frequently Whiggish or capable of being so interpreted, less often Locke than some others, might appear in a shelf of fewer than ten or twenty volumes. Any southern newspaper advertisement of books for sale, from Maryland in 1730 to Georgia in 1790, was sure to include an impressive proportion of historical and political and legal material, by no means all of it aimed at professional lawyers or public officials or wealthy planters.

There is a long and fairly complex background for all this interest. From the first landings at Roanoke Island or Jamestown, every settler was conscious that he was making history. Sir Walter Raleigh’s History of the World (1614) was read in the southern provinces during all the seventeenth century and was still being bought (usually in new editions) through the 1790s. It is concerned, of course, with the ancient world, but along with actual classical histories (to be noted here) it afforded the Anglo-American food for thought and comparison, along with moral teaching. Almost as popular in New England as in the Southeast, Raleigh’s great compendium was read in both areas for these and for different reasons. The same might be said of Hooker’s Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity (1594–1597), which was read in early Massachusetts as well as the Chesapeake and Carolina country, even though it justified the Anglican position in church government. All this material was purposeful in both the narrow modern and broader eighteenth-century senses, for it offered practical guidance as well as intellectual or even aesthetic satisfaction. Tastes changed and new books, developing older doctrines or theories or explaining new ones, appeared in ever increasing numbers throughout the eighteenth century. But even in the final decade after the adoption of the Constitution, the southern library continued to have a large proportion of volumes on law, history, and politics.

Though Henry Adams disparagingly declared that Virginians (and other southerners) by 1800 were exercising their minds only in law, politics, and agriculture, he was perhaps only half-consciously suggesting a truth, that eighteenth-century southern interests were primarily or basically secular, as opposed to or contrasted with New England’s. Actually, creative thinking and expression on agriculture was almost entirely confined to the nineteenth century, beginning with John Taylor of Caroline and Edmund Ruffin and John Beale Bordley and certain Carolinians. But law and politics, combined with history, were a major southern interest, partly from necessity and partly from pleasure in contemplation. The middle and northeastern libraries contain in general, though in lesser proportion, the same books on these subjects as do the southern, and colonials to the north had largely the same motives as their southern neighbors for owning them.

All fairly well educated Anglo-Americans knew of the reasons advanced by classical historians and political theorists for pondering the past. Stephen Bordley of Maryland in 1739 recommended, above all authors, Cicero and then Polybius, and in 1800 Thomas Jefferson declared that Tacitus was “the first writer in the world.” They and their contemporaries quoted these and other ancients on the uses of a knowledge of things that had gone before. These colonials paraphrased Graeco-Roman authorities and contemporary British writers, and added their own reasons for studying the record of man’s individual and societal behavior. Stephen Bordley, the Annapolis lawyer, advised his friend Matthias Harris:

The best way that I know of to avoid those Fatal consequences which you suppose may Result from Errors in Opinion on ye Subject of Government, is first to get well grounded in ye Original End & design of Government in General, by reading the best Historians and other books which treat on the Constitution of our mother Country on which We so much depend, and next to Consider what Arts or Steps have been regularly taken among ourselves toward making a difference between the English Constitution & our own here, & what not; & when all this is done, a man ought to be well aware of Byasses from Interest Passion friendship Authority or any other motive but ye pur dictates of Right Reason.

Bordley made several sententious but significant comments to Harris and to his own younger brother on methods of learning history, and of his personal reaction to reading Rapin’s and Rollin’s works and some quite different chronicles. His fellow Marylanders, such as the Carrolls, both Roman Catholic and Protestant branches of that family, were as concerned with reading as he. One barrister Protestant Carroll, educated in Britain, asked his London agent to keep him supplied (in 1764) with every political pamphlet he could find, as well as numerous Whiggish or Whiggishly inclined histories. His Roman Catholic cousin, Charles Carroll of Carrollton, French and English educated, later signer of the Declaration, an avid book collector of even the principal deistic and atheistic writers of his time and also of Whiggish historians, early in his life (1759) received from his father the planter, Charles of Doughregan Manor, a significant bit of advice representing upper-class attitudes toward legal knowledge:

It is a shame for a gentleman to be ignorant of the laws of his country and to be dependent on every dirty pettifogger.… On the other hand, how commendable it is for a gentleman of independent fortune not only [not] to stand in need of mercenary advisers, but to be able to advise his friends, relations, and neighbors of all sorts.… Suppos you will be called on to act in any public character, what an awkward figure you would make without knowledge of the law either as a legislator, judge, or even an arbiter of differences among your neighbors and friends. Apply as if your whole and sole dependence was to be on the knowledge of the law.

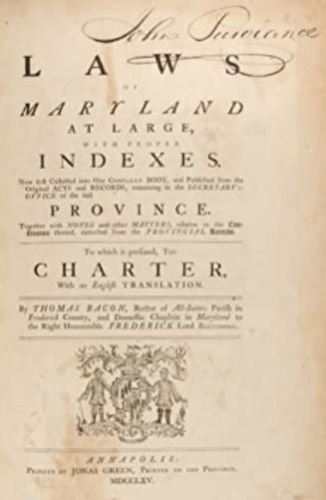

The younger Carroll, then studying at the London Inns of Court, may not have needed this advice. But across the Potomac in Virginia a decade later, planter Landon Carter, probably the most prolific pamphleteer of his colony in the pre-Revolutionary period, addressed his less intellectual son, Robert Wormeley Carter, in similar vein in a note inscribed in a copy of The Acts of Assembly, now in force, in the Colony of Virginia (1769): “This volume contains the Laws of your Country, and as no Gentleman should be ignorant of them I am persuaded I shall not stand in need of any arguments to enforce my desire to you.” The elder man warned that the study of such statutes might at first prove dull and insipid but that it would produce an informed citizen capable of judging the values of these and other laws, and even of advising friends concerning possible legislative action.

Almost twenty years later, Jefferson wrote to his future son-in-law Thomas Mann Randolph:

“I have proposed to you to carry on the study of law, with that of Politics & History. Every political measure will for ever have an intimate connection with the laws of the land; and he who knows nothing of those will always be perplexed & often foiled by adversaries having the advantage of that knowledge over him.”

Jefferson’s neighbor, Dr. George Gilmer, possessor of a wide-ranging and thoughtful mind and a well-stocked library, pondered and interpreted the meaning of the Revolution in his commonplace book in terms of politics and history. He quoted from David Hume’s Essays:

“Mankind are so much the same in all times and places that history informs us of nothing new or strong in this particular. Its chief use is only to discover in all varieties of circumstances and situations, and furnishing us with materials from which we may form our observations and become acquainted with the regular springs of human action and behavior.”

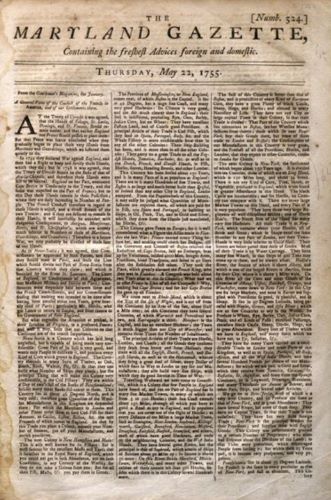

These men and their contemporary colonists had often read and frequently referred to well-known theories as to the uses of history in politics and the possible methods of studying both. Principally, they refer for theory to the classical historians or to English and (more rarely) French eighteenth-century thinkers, all represented on their shelves. The republican or radical British Whigs of the later seventeenth century and their heirs of the earlier eighteenth, the moderate Whigs and the moderate conservatives of integrity, such as Bolingbroke, as well as the later conservatives of the Hume-Burke variety, were among those whom these colonials pondered but whose advice they did not necessarily follow. Most early Americans shared with many of these writers the cyclical theory of history, which involves that discipline fundamentally with politics and law: that what has happened will or may happen again. Thus one pseudonymous southern essayist in the Maryland Gazette in 1745 produced with this sort of reading in his background perhaps the most thoughtful comment of the American eighteenth century upon the uses of history.

Caroline Robbins in The Eighteenth-Century Commonwealthman and her many discerning studies of individual writers, Richard B. Morris and his group’s evaluations of colonial Americans and law, and Trevor Colbourn in The Lamp of Experience: Whig History and the Intellectual Origins of the American Revolution examine in detail (albeit uneven detail) Anglo-American and American knowledge and employment of Old World ideas. All insist, and rightly, that no book or group of books incited men to revolt. Most of these historians (including some not named here for lack of space) have concluded that what occurred was a conservative revolution. Howard Mumford Jones calls the creation of the New World republic the last great triumph of the Enlightenment, and of course he does not attribute that creation to particular European books or philosophers. Bernard Bailyn, in his Pamphlets of the American Revolution and elsewhere, holds to his “old-fashioned view” that independence was the result of an ideological movement, a movement only in part inspired by Old World political theory. In all this is the implicit or sometimes expressed assumption that colonial law, history, and politics differ little in the three major groups of colonies. Though the presence of slavery has always been felt and noted, its apparent failure to affect southern libertarian action, appreciably or negatively, has never been satisfactorily explained, though Edmund Morgan recently made a magnificent effort to do so.

Colbourn devotes a chapter to Jefferson and has little else to say of other southern owners of politically slanted books, though he borrows his title from Patrick Henry, and, as previously noted, Richard Bland, Daniel Dulany, Jr., and Charles Carroll of Carrollton receive some attention. Madison is barely mentioned. The rest of the founding fathers from south of the Susquehannah are ignored, though a few names are recorded in passing. It is not our intention to claim that southern intellectual interests were drastically different from those of the colonists to the north, or that southern intellectuals were true liberals in any twentieth-century sense, or that widely read southern revolutionists were the only begetters of the Republic. But a look at southern reading in matters related to government and society may offer some indication as to why they supplied leaders, and perhaps the greatest proportion of major leaders, in the creation of the United States.

Books on law appeared on southern shelves long before the eighteenth century. Under the Virginia Company before 1624, books at Jamestown include volumes of English statutes and Sir William Stanford’s Les Plees del Coron [The Pleas of the Crown (first ed. 1557)]—the latter title owned by Jefferson in a 1583 edition in the early nineteenth century and by many others between. More popular from its first publication in 1678 was Sir Matthew Hale’s Pleas of the Crown (in Latin or English) and, later in 1716, William Hawkins’s A Treatise of Pleas of the Crown. These books were almost indispensable for colonial courts or legislative assemblies and practicing lawyers, but like most other collections-with-commentary of legal practice, they were also found in the libraries of planters, physicians, and clergy.

In the older southern colonies the printed laws of the particular provinces, complete or abridged, were the most popular legal items recorded in library inventories. Mercer’s Abridgment and its local popularity have been noted, but somewhat more remarkable is the frequent presence of certain expensive volumes such as Thomas Bacon’s Laws of Maryland at Large (Annapolis, 1765) and Nicholas Trott’s The Laws of the Province of South Carolina (Charleston, 1736). There were also many lesser editions for individual colonies, and widely distributed to members of provincial legislatures and county commissions of the peace were the official periodic compilations published by the authorized printers in the various capitals. The most popular legal title in South Carolina, next to Trott’s Laws, was British Thomas Wood’s Institute of the Laws of England, and it is frequently on the shelves of Chesapeake colonials. Useful to layman as well as lawyer were Giles Jacob’s A New Law Dictionary (1729) and Henry Swinburne’s ubiquitous ecclesiastical law volume, A Briefe Treatise of Testaments and Last Wills (1590, and eight other editions by 1743, with another in 1803), the latter almost always listed as “Swinburn on wills.” Sir Edward Coke’s Reports and Institutes of the Laws of England, in many editions, was in the larger libraries from the seventeenth century. Jefferson, who owned several volumes of the great works, in his college days referred to Coke as “an old dull scoundrel,” but many years later praised the Institutes as “executed with so much learning and judgement that I do not recollect that a single position in it has ever been judicially denied.” In the colonies, where parents too often died young, John Godolphin’s The Orphan’s Legacy (1674) was most useful, as was Swinburne’s work (classed as ecclesiastical law), for the matters of the wills and legacies and duties of execution here discussed were functions in Britain of the ecclesiastical courts.

Lawyers had to afford these books and others felt they had to. In every parish vestries were concerned with children left with guardians or with guardians who failed in their duties. Professional men, seamen, merchants, and planters, great and small, were vitally concerned with land, and this meant litigation, as well as the recording and conveyance of deeds.

Everywhere in the South, as in rural England and to some extent in the northern colonies, one of the first duties of a man who held property was to serve as a justice on a county commission of the peace. As noted, even in the seventeenth century few if any colonial justices were illiterate (there are indications that in the eighteenth century a scattered few, serving along the extended frontier, may not have been able to read and write). The first public office held by almost every legislative and judicial and even military leader in the century of the Revolution was on the commission of the peace, though family founder William Fitzhugh was a member of the Virginia House of Burgesses before he became (in 1684) a Stafford County justice. He lived in a frontier county on guard against Indian depredations, but there is every indication that his fellow justices were, as he was, far more than merely literate. Though he was a practicing barrister as well as a large landowner, the other members of his commission, as far as is now evident, had no formal legal training. Actually most county commissions of the peace were made up of landowners, and occasionally merchants, whose knowledge of judicial matters came from volumes of statutes and procedures such as those just mentioned, from experience in the “lesser” cases, such as their courts handled, but most specifically from one or more of the remarkable manuals designed for the guidance of amateur and professional jurists in rural England and in the colonies. Jefferson owned, and apparently used, several of these guides, as did the learned South Carolina Chief Justice Trott two generations earlier, and all sorts of people who did not serve in judicial capacities. At county seats were frequently collections of these and other legal works, designed for the particular use of the justices but in fact borrowed and read by many other persons and paid for through the county levy.

Jefferson’s manuals included two seventeenth-century and three eighteenth-century British aids to justices of the peace, and two Virginia-published and -authored eighteenth-century similar works. George Webb, a justice of the peace in New Kent County, had printed at Williamsburg in 1736 The Office and Duty of a Justice of the Peace … Collected from the Common and Statute Laws of England, and Acts of Assembly, now in force; and adapted to the Constitution and Practice of Virginia, one of the earliest of its kind produced in the colonies. Along with it, Jefferson had William Waller Hening’s The New Virginia Justice, comprising the Office and Authority of a Justice of the Peace, in the Commonwealth of Virginia (1795), by the later compiler of the famous Statutes at Large of Virginia. There was, in addition, attorney Richard Starke’s Office and Authority of a Justice of the Peace (1774), by a Virginian of legislative and magisterial experience. In Charleston an assistant judge of the court of general sessions, William Simpson, in 1761 published The Practical Justice of the Peace and Parish-Officer of … South Carolina, a best seller in that colony from the time it appeared.

British manuals much used by southern settlers included Michael Dalton’s (1618), Sir Richard Bolton’s (1638), Joseph Keble’s (1689), William Nelson’s (1710), Joseph Shaw’s (1728), and Richard Burn’s (1755), all of which continued to appear in new editions that were sold in the colonies up to and during the Revolution and referred to long after that time. Of these, the manual most frequently present from Maryland through Georgia was Dalton’s The Countrey Justice; containing the practice of the Justices of the Peace as well in as out of their Sessions. In rural Britain and America, magistrates found this earliest handbook of its kind a prized resource. Aphra Behn, the seventeenth-century English dramatist, in her perhaps satiric and at least facetious play The Widow Ranter, or, The History of Bacon in Virginia (composed c. 1688), jibes at New World uncouthness, especially in her court scenes depicting provincial jurists as dependent on Dalton without being able to read him. As in another work of hers, Oroonoko, roguish and boorish colonial officials are the butt of her ridicule, and she has one magistrate say to another: “Why Brother though I can’t read my self, I have had Dalton’s Country Justice read over to me two or three times, and understand the Law” (Works, ed. Montague Summers; 5 vols., London [1915], 4:264 [act 3, sc. 1]). The allusion applies as much to British rural illiteracy as to southern colonial but perhaps is indebted most to the comic Shakespearean constable-country magistrate tradition. Though as a scholar has shown recently, the idea of American illiteracy she may have inferred from the historical report-documents employed as her source.

Emphasis in Dalton is on the English common law and the statutes in some of the collections noted above as widely held in the southern colonies. One can be more than reasonably sure that every southern colonial legislator and judge, every administrative official, every professional lawyer, every landholder of at least several acres, and every justice of the peace and vestrymen owned or had available Dalton’s Countrey Justice. The colonial period, one repeats, was a litigious age, in which royal governors seem to challenge or to tax or to usurp the colonist’s right to land, or the conveyance of title to various sorts of property (including exports and imports), or certain aspects of personal liberty. Lesser and petty crimes had to be considered by lay judges in thinly populated areas. Everyone who could read turned to Dalton and the provincial or English statutes to find out whether he was receiving or how he was administering justice. Colonial assemblymen were arguing legal right, personal and political, from their first 1619 session at Jamestown straight through and beyond the 1788 constitutional debates. Whenever they spoke or wrote, they buttressed their arguments in the New World situation with references to printed laws and legal commentaries.

Almost surely among the books John White lost at Roanoke Island were some histories of the ancients and of the British peoples. Certainly from early Jamestown there were copies of Greek and Roman and British chronicles and biographies. Internal evidence in the Virginia-composed first New World writings (1608, 1609?) of John Smith, William Strachey’s Historie of Travell into Virginia Britania (1612), and George Sandys’s Ovid’s Metamorphosis (1626) suggests that these colonists had classical histories and sixteenth-century British annals (among other books) with them in the “rudeness” of America. William Camden’s Britannia (1586 in Latin, 1610 in English) and Sir Richard Baker’s Chronicle of the Kings of England (1641, 1643) were in several colonies during the seventeenth century and continued in popularity all through the eighteenth. Alongside them, but covering only some centuries of the ancient world, was the already noted enormously popular, indeed ubiquitous, Sir Walter Raleigh’s History of the World (1614 and dozens of later editions) and Plutarch’s Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans in North’s sixteenth-century, Dryden’s seventeenth-, and the Langhornes’ eighteenth-century translations or in Latin-Greek versions (several of the last were owned by Jefferson). Some editions of two later writers were offered for sale in town and country in southern states at least as late as 1797. Camden and Baker were antiquarian, detailed, and anecdotal and supplied British people with their own history in editions popular until sometime after Rapin’s (French 1724, English soon after). The “incomparable Plutarch” was read for moral and historical instruction throughout the American seventeenth century, and in the eighteenth for backgrounds “for liberty in a republican garb.” Raleigh offered Christian history, with divine providence as a guiding force. He warned against the false wisdom and errors of political leaders and against tyranny as the most detestable form of government. He extolled monarchy and denounced democracy as the tyranny of the multitude, and he saw history as moral instruction, to be presented in the form of pen portraits of major historical personages.

Flavius Josephus’s History of the Jews was owned in every colony—in Greek, Latin, or English—by clergymen, physicians, planters, public officials, and other folk from the latter seventeenth century to 1798. Every man who wanted to be intelligent about Old Testament matters felt he must have a copy. It was the second most popular history in South Carolina. In 1709 William Byrd II read it in the Greek version before breakfast. Jefferson owned several editions in Latin or English. The third president also owned Polybius’s General History, as had other southern colonials since the 1690s at latest. From this stiff moral history they learned how earlier empires had risen, flourished, and declined, and inevitably compared them with the far-flung domain of which they were a part. Perhaps Polybius did not come into his own until the constitutional debates of 1787–1788, but he was on the southern bookshelf long before.

Another sort of chronicle popular before 1700 was John Rushworth’s Historical Collections of Private Passages of State (1680–1692), an account of parliamentary matters in the stormy years of the Puritan revolution, and sometimes interpreted as having a parliamentary bias. It was still a usual item in medium or large southern libraries in 1798. Edward Hyde’s (earl of Clarendon) History of the Rebellion (1702–1704), written in the seventeenth century, was a Tory account of considerable literary merit and integrity. Bishop Gilbert Burnet’s History of the Reformation of the Church of England (1679–1714) and History of His Own Time (1724–1734), liberal Whiggish interpretations of recent British history, were read all through the eighteenth century in every southeastern province. They were on Jefferson’s recommended lists of historical reading. Lawrence Echard’s Roman History (1698/1699), largely derivative and monarchical, was for much of the eighteenth century the most popular account of the ancient republic, from “the Building of the City to the Perfect Settlement of the Empire by Augustus Caesar.” The same author’s History of England (1707–1720), from Julius Caesar to the end of the reign of James II, is an entertaining Tory account in the Clarendonian tradition, the most popular history of England in America until Tindall’s translation of Rapin. Also of the first part of the eighteenth century is Bishop White Kennett’s Complete History of England (1706), widely read from Maryland to Georgia. Kennett incidentally is also remembered as an original member of the S.P.G. and as compiler of the first exclusively American bibliography, Bibliotheca Americanae Primordia: An Attempt Towards Laying the Foundation of an American Library … (1713).

Thus by the beginning of the eighteenth century the southern colonial reader was familiar with dozens of histories of the ancients and of Britain, almost all of them secular and usually didactic. They were almost all also monarchical, though many of them place stress on personal liberty and, directly or indirectly, on the possible clash between governmental or crown prerogative and the liberty of the subject. Readers who were conscious of the cyclical concept were to increase in the new century, but in the story of their own country or of ancient Greece and Rome they had already noted examples of rise and decline. Translators of the historical classics and later seventeenth-century historians of contemporary Britain were influenced, sometimes almost imperceptibly, by what had just happened or was happening in England, such as the Puritan revolution and Commonwealth, the restoration of the Stuarts, the Glorious Revolution of 1689, and by the purely political writings of Hobbes and Filmer, Harrington and Sidney and Locke, who (with others) are to be noted in a moment.

The new histories of the eighteenth century were even more influenced by particular political ideologies than were the earlier accounts. At the same time they were of broader scope, for they were concerned with Carthage and Egypt as well as Greece and Rome, and with modern continental Europe as well as Great Britain. Copies of the Universal History (compiled by many hands, and in the first twenty volumes [1747–1755] concerned with the ancient world) were surprisingly widespread, especially considering their cost and size. Puffendorf’s Introduction to the Principal Kingdoms and States of Europe, though the first English version was in 1695, marked a pattern of broadening historical interests in its several eighteenth-century English and French editions.

French writers, in their own language or in English translation, were with few exceptions the most widely represented interpreters of England and even of the ancient world. Charles Rollin, Jansenist rector of the University of Paris, published his readable and instructive Ancient History in 1730–1738, and after his death his Roman History was completed by friends and brought out about 1741. Both appeared in new editions throughout the century, and an eight-volume printing of the Ancient History appeared in Boston as late as 1805. Both were read widely throughout our first national period. At least one of them appears in a 1767 Georgia library, in numerous pre-Revolutionary newspaper advertisements, in mid-eighteenth-century Maryland sermons and letters, in John Randolph of Roanoke’s recommendations to a young relative, in John Breckinridge’s books (carried to Kentucky in 1792), in the collections of individuals and groups in the Carolinas, and in 1797 in the inventory of a Lunenburg County Virginia country store. One should add that the books were favorites of John Adams and his family in Massachusetts. Though Rollin’s works have been called shortcuts to the classics, they offered much more to their readers, for they proceed from the cyclical theory and they are theistic. A recent study has shown that Rollin’s influence complements that of “the dissident Whig authors” who kept alive a republican ideology in Walpole’s England and in his America. By 1800 the books were available in free schools and mechanics’ apprentice programs, for they seemed to preach that the republican cycle in America must continue or all would be lost.

Southern colonials as well as some other Americans showed great interest in the histories of revolutions in the western world by Abbe’ Rene’ Aubert de Vertot. Though Jefferson owned a 1689 first edition of the story of the revolution in Portugal (as well as a much later English edition), his other works by this author were eighteenth-century printings. Vertot’s Revolutions of the Roman Republic was offered for sale many times in Williamsburg between 1751 and 1772 and was owned in Charleston in 1750 and in Baltimore in 1798. The accounts of revolutions in Sweden and Spain were in libraries in Maryland, Virginia, Georgia, and South Carolina. Though the author uncritically repeated certain ancient historians, he had a talent for narrating and interpreting, with an eye on current French affairs, which contributed to the popularity of his books for a full century. He stressed love of liberty as the first motive in founding the Roman Republic and the Romans’ nobility of character as long as they remained husbandmen and called “their greatest Captains from the Plough to command their Armies.” These were among the reasons why he was read. Though he was not quite as popular as at least three English and another French historian, he had a considerable following in the South. See, for example, the references to him in the Virginia Gazette Index.

Though he came relatively late upon the eighteenth-century scene, Voltaire and his histories appear frequently in the library lists of every southern colony: his Age of Louis XIV, the History of Charles XII of Sweden, the History of the Russian Empire, the General History of Europe, and several other titles. The Anglican Reverend Thomas Cradock of Maryland, a learned litterateur, owned the 1759 edition of Voltaire’s Essay on Universal History. John Randolph of Roanoke wrote that one of the first books he read (c. 1780–1781) was the History of Charles XII. Rousseau sent volumes of the same work to his friend, Dr. George Gilmer of Albemarle. Parson Weems, the itinerant bookseller extraordinary, sold hundreds of copies of Voltaire’s histories in all the southeastern states in the 1790s and early 1800s. Country stores in Virginia carried Voltaire’s Works in stock. Devout Roman Catholic Charles Carroll of Carrollton in 1771 asked to have all new Voltaire essays sent to him from France. A Maryland sheriff and Virginia and North Carolina governors, physicians, and planters owned many Voltaire titles, but his histories were most frequent. “An ‘infidel’ but a great historian,” a Presbyterian scholar-cleric of 1800 insists, and he gives the Age of Louis XIV (1751, [English 1752]) pre-eminence as the first work to show how “intimately revolutions, and other national events are often connected with the current of literary, moral, and religious opinions; and how much a knowledge of one is frequently fitted to elucidate the other.” One should remember that in Louis XIV Voltaire condemned the persecution of French Protestants, though he also blamed them for obstinacy in small matters. His biting comment on English dissent was allowable because he was even sharper in his allusions to Catholicism. His Philosophical Dictionary (1765), with its strangely anti-Christian bias, seems not to have been read much before the end of the century. All together, Voltaire’s remarkable popularity in the eighteenth-century southeast may be another suggestion that that region’s culture was basically secular.

Throughout the century—at least from its first appearance in English in 1725–1731—Histoire d’Angleterre (orig. ed. 1724), by the French Protestant and Whig Paul de Rapin-Thoyras, was the most popular account of the mother country in the southeastern colonies and states. As the Whigs had done since the late seventeenth century, and indeed as Sir Henry Spelman and others had done earlier, Rapin felt the necessity of going back to the Anglo-Saxons to explain English democratic institutions and constitutions. He traces English history from Julius Caesar and brings it through the reign of Charles I. Most southern colonials owned the English edition, improved with notes by the translator Nicholas Tindal, who later continued the story to the end of the reign of George I. Before 1732 Robert Carter of Virginia owned the combined Rapin-Tindal version in fifteen volumes, and it seems to have been the history owned by the Reverend Richard Ludlam of South Carolina by 1728. Though its ultra-Whiggish point of view cannot account for all of its popularity, the fact that colonials saw the history of the mother country through this essentially republican interpretation must have influenced their minds from the 1730s. Almost always colonial readers refer to Rapin with approval, an interesting exception being Maryland lawyer Stephen Bordley, who wrote in 1739 that since he had read the first volume of the history he thought less of the author he had known previously only by repute. Jefferson, who like William Byrd II and Dr. William Fyffe of South Carolina and others owned a French edition, told a friend as late as 1815 that “it was still the best history of England, for Hume’s tory principles are … insupportable,” and in 1825 wrote another friend that “of England there is as yet no general history so faithful as Rapin’s.” One should recall that among eighteenth-century histories he owned not only Hume but Whiggish Catharine Macaulay and the shorter and more recent (London, c. 1796–1801) history by John Baxter, the last of which he attempted to have reprinted in America. He also had a copy of Oliver Goldsmith’s History (1764). But this French exposition and narrative of the prerogatives of the crown and the rights and privileges of the people, with the observation that the Saxons did not invest their kings with the power of changing laws when they pleased or of raising taxes at their pleasure, remained for Jefferson and his countrymen the most satisfactory account of their European progenitors, obviously in part because it fitted conceptions already arrived at from experience and from other political theorists. Again one must note that Rapin’s popularity was not confined to the South, though Daniel Dulany, Sr., Charles Carroll of Carrollton, Richard Bland and Thomas Jefferson, Henry Laurens and John Joachim Zubly were among the Frenchman’s attentive readers.

There were English historians in the eighteenth century who wrote of their own country, and several of them were relatively popular, for various reasons, in the South. Novelist Tobias Smollett’s Complete History of England, From the Descent of Julius Caesar to the Treaty of Aix la Chapelle appeared in 1757, with a continuation in 1763–1765. Smollett’s predilection for the Whig point of view wore off, he said, as he proceeded in its composition. Yet his historical work is hardly as strongly Tory as that of his fellow Scot David Hume. Smollett’s work was enormously popular in America from its first appearance. The inventories indicate that southern colonials, such as D. P. Custis, bought Smollett’s narrative in the year of its first appearance, and advertisements in the Virginia and South Carolina gazettes indicate that the first edition, and then the first edition with the Continuation, were offered in colonial bookstores within a year of their publication. The latter was still offered in a country general store in Virginia in 1797.

Another novelist, Oliver Goldsmith, was read in the South for his Greek (1774) and Roman (1768) histories—potboilers recommended to nephews by Jefferson, who suggested, especially for them, Goldsmith’s slightly earlier History of England, in a Series of Letters from a Nobleman to His Son (1764). In 1796 traveling salesman Mason L. Weems sold seventy-five complete sets of Goldsmith’s writings, including the histories, in Richmond alone. William Robertson, Scottish educator and author of such classics as the History of the Reign of the Emperor Charles V (1769, with a Philadelphia edition in 1770), produced two other works that were read in the eighteenth-century South, History of Scotland (1759) and History of America (1777), which are found fairly frequently in libraries from Maryland to Georgia. A robust Presbyterian Christian opposed to Whitefield and “enthusiasm” and on cordial terms with Hume and Gibbon, he was commented upon most unfavorably for his history of America by Jefferson in 1785, who called him a “compiler only of the relations of others.” Not surprisingly in view of the Caledonian element in the population of the Southeast, his History of Scotland is found more often in southern libraries than is his America.

Politically the two most significant British historians of their own country during the eighteenth century, both widely read in the South, presented English history from widely differing points of view. Catharine Macaulay, ardent Whig and controversialist, who declared she had from early youth read with delight those historians “that exhibit liberty in its most exalted state,” published the first volume of The History of England from the Accession of James I to that of the Brunswick Line in 1763. It was never completed, but nine volumes were published with additions by 1783. Her volumes were widely advertised and sold from Baltimore through Charleston, and in 1784 she visited George Washington at Mount Vernon. Jefferson had a complete first edition of the nine volumes; and long before they were completed, Whiggish Virginian James Maury ordered all volumes that had appeared through his Tory friend and fellow clergyman Jonathan Boucher, who lived at a seaport as Maury did not.

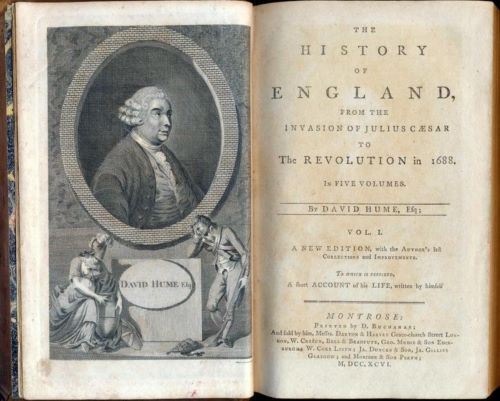

Quite different but represented by even more southern examples, perhaps because it was published earlier (in 1754–1759), was the famous history by the political conservative and religious sceptic, the Scot David Hume. His History of England from the Invasion of Julius Caesar to the Revolution of 1688 was read by the religious orthodox and the sceptical as well as by the liberal and conservative (in varying ways) southern colonists. They were still buying this book in 1798 and into the next century. Charles Carroll of Carrollton bought the volumes as they came out. Hume’s Toryism, modern scholars more or less agree, was more superficial than that of Burke or Bolingbroke. His political ideas, showing the detachment and discernment of the sceptic, have many qualities in common with those of the British liberal Whigs of his time, as do his ideas on parliament and on change of government and on party. But he did not believe in the social contract as the basis for liberty, that the growth of wealth and civilization endangered liberty, as did those radical Whigs. He held that Americans were unconquerable and wished his government would crush demagogues instead of trying to crush colonists. Though the orthodox Presbyterian parson Samuel Miller in 1800, weighing Hume’s qualities as a historian, could declare that the Scot’s work deserved comparison with the best produced in Greece and Rome, rationalist Thomas Jefferson, who may have felt some compatibility with Hume in his religious views, condemned the historian. Jefferson bitterly resented Hume’s popularity: “I remember well the enthusiasm with which I devoured [the History] when young, and the length of time, the research and the reflection which were necessary to eradicate the poison it had instilled in my mind … it is this book which has undermined the free principles of English government … and has spread universal toryism over the land.” Needless to say, Hume’s History is not on any of Jefferson’s many lists of recommended reading. As Douglass Adair has shown, however, James Madison probably owed some of his profoundest insights into the dangers of faction and the advantages of large republics to Hume’s political essays, which were as well known in America as the History. But there is little evidence that Hume was a profound or (from a liberal point of view) pernicious influence anywhere in America.

As this brief survey of library volumes on law and history may suggest, it is doubtful that more politically minded people ever lived among the British than the southern colonials. From the days of the Virginia Company of London, they were always concerned with their rights as Englishmen. The charters granted to the Virginians under the company and then the crown, the Proprietary Charters and Fundamental Constitutions of Maryland and the Carolinas, all explicitly or implicitly reflect royal or parliamentary prerogatives in some relation to colonial rights. Incidentally, religion was never the primary factor in determining home government and southern colonial relationship, though it was at times a factor. But from Captain John Smith as president of the council (1607–1609), and including early governors Yeardley and Wyatt and their first General Assembly of 1619, through later legislatures and individuals from Maryland to Georgia, bitter attitudes were often expressed toward authority in Britain acting as prerogative— an authority which failed to understand colonial problems because it had not experienced them. And frequently, in more friendly tones, messages and reports were sent back to the Board of Trade and the Plantations explaining colonial needs in taxes, land policies, provincial and parish church organization, militia, and agricultural incentive, among a dozen other matters. Surviving journals of councils and houses of assembly and printed, enacted laws indicate how earnestly colonials pondered and debated these things. One should read, for example, the arguments of William Fitzhugh in the 1680s as to the necessity for the immediate validation of enacted colonial laws and the proper relationship of parliaments to superior courts, the first based on a mixture of experience and English precedent, the second ostensibly on English precedent alone. Or one should see the Virginia legislature and judicial records of a generation later, with their evidence of Sir John Randolph’s learned familiarity with English parliamentary procedure. Parallel situations appear in the legislative documents of the proprietary colonies even before they were taken over (in the case of Maryland not permanently) by the crown. Many colonial governors, though they were convinced British imperialists, developed such an interest (including economic) in their provinces that they too presented arguments from the American point of view to home authorities. Viceroys and legislators were careful to cite English political and legal precedent in presenting almost any case. When the colonials finally came to protest the Stamp Act and then to state reasons for independence, their oral and written polemics were studded with references to British political writing and constitutions, as well as to general history.

Whether mid- or later eighteenth-century political arguments came basically from need and experience and were bolstered by precedents from the writers of antiquity and the Renaissance and their own time, or whether the rebellious Americans got their ideas of their rights from their libraries and reading, has long been discussed, with the frequent conclusion that local and immediate incentive came first, books second. Certainly political writing was a conscious and cited asset of the New World southern settler in expressing his strong feelings. What may be glanced at here are the principal political materials he had on his bookshelves, in addition to the already noted legal and historical volumes which were (even the classics) profoundly political in point of view.

Early in the seventeenth century some of these materials were already in the colonies. A clergyman in 1635 is the first recorded owner of a copy of Richard Hooker’s Of the Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity (1594–1597), the classic of the English Reformation settlement and justification of the Anglican position in church government, a work often referred to in secular political pamphlets or treatises to the end of the eighteenth century. Copies were sent by the famous Dr. Bray to Maryland and South Carolina before the end of the seventeenth century, and even earlier a copy appears in the library of Governor Francis Nicholson (successively of Maryland, Virginia, and South Carolina). All through the eighteenth century—from a planter’s inventory of 1701, South Carolina’s Chief Justice Trott’s reference in 1703, the library lists of North Carolina Governor Arthur Dobbs in 1765, and a number of libraries of clergy and planters (including Richard Bland’s in 1776, Edward Lloyd’s in 1796, the Library Company of Baltimore’s in 1798) to Thomas Jefferson’s collection—may be found Hooker’s great book. Jefferson, significantly, included his 1723 edition in his classification “Politics.” The sixteenth-century Florentine, Machiavelli, a prolific writer best known for The Prince and in our period also for Discourses on Livy, and recently hailed as the transmitter (through Harrington) of certain classical political ideologies, is no longer labeled the epitome of wily and unscrupulous politics, though in the nineteenth century, and often since, he has been so characterized. His opposition to mercenary armies and his belief in a native militia, for example, may have come from the Greeks and Romans, but it was carried on by Harrington and the neo-Harringtonians of the end of the seventeenth century into the eighteenth and became a familiar issue (though really a bogey) with the southern colonials, who mention it in their Revolutionary period pamphlets and long before in all their provincial newspapers. Machiavelli is referred to both favorably and unfavorably, as early as 1624, in a recently published letter from English country gentleman George Wyatt to his son, the Virginia resident, colonial governor Sir Francis. Evidently the older man thought the younger knew Machiavelli well or had this Florentine’s works with him at Jamestown. Sir Francis, clearly, was to be the kind of good albeit strong magistrate recommended by Machiavelli and by the so-called Real (Radical) Whigs almost a century later. George Wyatt refers to Polybius and Machiavelli on the proper organization of a militia, with the obvious assumption that such a volunteer army will be the colony’s fighting force. Like Hooker, Machiavelli stood on southern shelves throughout the eighteenth century, owned by clergymen and lawyers and planters, including at least a Maryland and a Virginia signer of the Declaration. Jefferson owned several editions, and Madison recommended in 1782 the complete Works as a necessity in the political section of the Library of Congress.

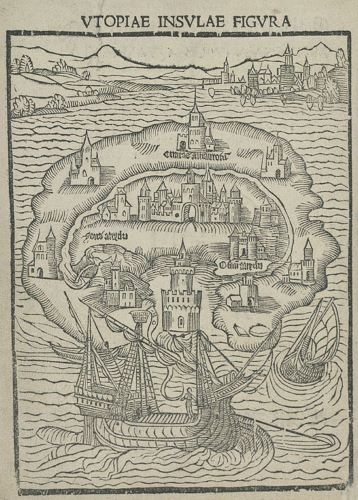

Other seventeenth-century or earlier political writers were more or less well known in the colonial South throughout that century, and sometimes through the next. Francis Bacon’s miscellaneous works, including his utopian New Atlantis (usually printed with the always popular Sylva Sylvarum), extended their influence and presence, not yet adequately measured, into the eighteenth century, though in the latter days it was never so popular as Sir Thomas More’s Utopia of an earlier time, which was to be found in dozens of southern collections before 1800. James Harrington, a writer hailed by a recent historian as the only legitimate English interpreter of Machiavelli for the eighteenth century and as “the central figure among the ‘classical’ [i.e., Graeco-Roman] republicans,” was represented on a number of shelves by The Commonwealth of Oceana (1656) throughout the eighteenth century. He differed from the later group of so-called neo-Harringtonians, which included Walter Moyle, John Toland, Viscount Molesworth, John Trenchard, and Thomas Gordon (also known as Real Whigs), in that he saw medieval politics as incoherent, whereas they identified the commonwealth of freeholders with the ancient (Saxon) constitution.

Besides certain later seventeenth-century libertarians (to be mentioned in a moment), southeastern colonials about the end of that century and all during the next sometimes had on their shelves the two best-known conservative political writers. Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan (1651) and other political discourses by him were in the Chesapeake provinces in the last decade of the seventeenth century and appear a number of times in the Carolinas in the eighteenth. Richard Lee II, owner of one of the large seventeenth-century libraries, which included Hobbes’s Philosophical Rudiments Concerning Government and Society (1651) and his De Corpore Politico; or The Elements of Law, Moral, and Politic (1650), as a staunch royalist must have approved of the notions they advanced of government by the aristocracy and monarchy. How he differentiated between Hobbes and that other conservative author Robert Filmer (in Observations Concerning the Original of Government [1652] and the now more famous Patriarcha [1680]), who disagreed with Hobbes on the means of acquiring absolute monarchical power in government and presented classic defenses of the status quo of Charles I, is not known. Filmer, who had a brother resident in Virginia, was represented on eighteenth-century southern shelves, as on those of Robert “King” Carter, Richard Bland, George Gilmer, and Thomas Jefferson. Libertarian Dr. Gilmer’s commonplace book shows how thoroughly the physician had read and how deeply he detested Filmer’s theories. The loyalist Reverend Jonathan Boucher of Maryland in A View of the Causes and Consequences of the American Revolution (1797) wrote, however, what Peter Laslett has called “the best common-sense defense of Filmer that ever was made.”

John Locke’s Two Treatises on Government (1690) was on a southern bookshelf before 1701. Boucher rejected Locke’s theories, but until very recently the latter has been hailed as “America’s philosopher,” the political thinker who led us to the Declaration of Independence and gave us some of its phrases. Locke’s libertarian and logical ideas, including his contract-compact theory of government (too familiar to be discussed here), were in southern libraries well before the end of the seventeenth century. In the past generation several historians reassessing our political heritage have shown rather conclusively that the works of Trenchard and Gordon were of greater influence, however, and were more widely known. One distinguished scholar states flatly that he can see no discernible evidence of the influence of Locke’s governmental ideas in America before the mid-eighteenth century, and to support his contention cites the scarcity of copies of Two Treatises in the colonies before that date. This scholar may not have considered the fact that the collected editions of Locke’s Works (1714, 1722, 1727, and 1740) contain the two political works and that, from at latest the 1730s, these editions were in Maryland, Virginia, and both Carolinas. Also, they were referred to or quoted in southern newspapers over a long period. It is highly likely that Locke’s insistence on moral law in politics, that no government could take its subjects’ property without consent, and the other now familiar principles he expressed were at least well known in the colonial South well before 1750.

Algernon Sidney’s Discourses Concerning Government (1698), published after this radical Whig’s “martyrdom” (execution) and directed toward “constitutional restrictions and readjustments” which would strip the monarchy of any arbitrary prerogative and redistribute political power in accordance with property, and expressing the belief that rebellion is often necessary (among other now familiar concepts), was in the eighteenth century frequent in southern libraries and continued so through at least the first national period. His book was owned by Robert “King” Carter in 1732 and by his grandson Robert of Nomini two generations later, by William Byrd II and Richard Bland and Thomas Jefferson, by North Carolina Governor Thomas Burke, South Carolinian Joseph Wragg, various library societies, and later by John Taylor of Caroline and Judge Spencer Roane and Benjamin Watkins Leigh, and dozens more north and south. His title-page motto was adopted by Massachusetts as its motto, but Sidney was no more popular in New England than in the Southeast.

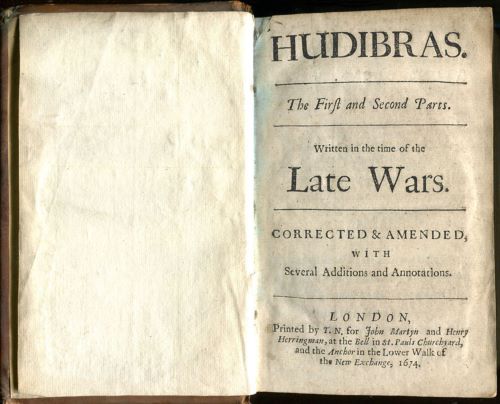

The strong Tory principles behind Samuel Butler’s famous verse satire Hudibras (1663–1678) were probably not entirely the reason for its enormous popularity in all the colonies below the Susquehannah. Its targets were human foibles as well as political principles, and it offered quotable lines for those of any party persuasion. Though only a few copies are recorded before 1700, the familiarity with its meter and phrases and persona shown by later seventeenth-century southern colonial writers is sufficient evidence of its presence. Actually there are more copies of Hudibras in libraries throughout the eighteenth century than of any other English poem in all five provinces. Obviously read more for its politics, yet curiously listed by some historians (who should know better) simply as travel literature, is Robert Viscount Molesworth’s An Account of Denmark as It Was in the Year 1692 (1694), a depiction by a deeply troubled libertarian of the nature and development of absolutism, the story of how a near neighbor of England gradually lost its representative government to a despotic monarchy. Caroline Robbins says that Molesworth was the most influential and widely quoted of the Real or Liberal Whigs during his lifetime and for a considerable period thereafter. In the South he is most evident in libraries inventoried about the middle of the eighteenth century, though he is still present in 1800. In the 1750s he was referred to in Virginia’s satiric “Dinwiddianae” poems, protesting a royal governor’s arbitrary exercise of prerogative. The poet appends a note recommending that every “true British Subject” read this book, especially for its examples of unjust taxation.

Frequently referred to were continental European political commentators Samuel von Puffendorf and Charles Louis de Secondat, baron de Montesquieu. Puffendorf, historian and lawyer and philosopher, as well as political writer, published editions of most of his work before his death in 1694, though many of his books were reprinted throughout the eighteenth century in Latin and English. The De Jure Naturae et Gentium and its resume’, De Officio Hominis et Civis Juxta Legem Naturalem, as well as An Introduction to the Principal States and Kingdoms of Europe, were in many libraries, medium and large and social or public in all five colonies. Among other principles, Puffendorf held that public law was not to be regarded as the will of the state but as the sum of individual wills (thus anticipating Rousseau), and that the state of nature is not one of war (as Hobbes believed) but of peace. Equally ubiquitous and perhaps more influential were several works of Montesquieu, especially French and English editions of his Persian Letters (orig. ed. 1721) and Spirit of the Laws (orig. ed. 1748). His discussions of the feedback and interplay between society and government, between natural environment and civilization, represent the subtlety and elusiveness of some eighteenth-century political expressions. Presbyterian parson Samuel Davies read him with pleasure but obviously without much understanding. Dr. George Gilmer quotes with approval his well-known aphorism, “Where law ends, tyranny begins.” Today, Howard Mumford Jones calls him an arch conservative, and another commentator, presumably agreeing with Jones, notes that he had a far-reaching effect on the framers of the Constitution. At Princeton, Madison studied The Spirit of the Laws as a textbook. Jefferson changed his mind about Montesquieu as the years passed, though as early as 1790 he warned his son-in-law that though The Spirit of the Laws was usually recommended for its presentation of the science of government, it was as full of political heresies as of truth. In his student’s commonplace book, Jefferson had copied many passages from this political and legal philosopher, but by 1810 he gave an even lower opinion of the book than he had in 1790. In 1811 he was sufficiently pleased with a considerably revised edition by Destutt de Tracy to write a “proem” for its first (Philadelphia) publication, underlining the paradoxes and misconceptions or misstatements of the original and declaring “Tracy’s Review of Montesquieu, the ablest work which the last century has given us.” Though a recent writer on the American Enlightenment sees Montesquieu as the most often praised and cited major French figure, one gathers from a brief survey of southern comments that the baron was never as frequently quoted in this area as in other colonies. The subject is perhaps worth investigation.

Of the half-dozen most popular writers on politics and government in the eighteenth-century South only one, John Locke, has so far been discussed. All the remaining five published their comments within the century and were strikingly varied in the literary forms they used. One wrote a tragic drama with a Roman title and setting; another wrote a French novel with classical origins, bearing as title the name of an ancient hero; the third wrote essays under the pseudonym “Cato,” and later his own political discourses, with his translation of the Roman historian Tacitus. The fourth writer’s major work in prose is as well known for its aesthetic and social philosophy as for its political, and the fifth’s is a pseudo-Whig journal as well as a study of the idea of a patriot king; the last writer is usually labeled either as a Tory or as a most conservative Whig.

Joseph Addison, major Whig statesman and, with Pope, the most popular secular writer in the colonies throughout the eighteenth century, produced in 1712 and published in 1713 the first great neoclassical tragedy under the title Cato. Written from a Whig perspective, it was capable of being adopted by Tories as well as Whigs as a presentation of the impeccable model of patriotism and virtue. As with other neoclassical literature, its purpose was didactic, “to inculcate virtue.” The protagonist may be entirely too admirable in his inflexibility against tyranny and in his magnanimity toward his enemies, but he was the ideal of readers and theatergoers in Britain and America for a full century. On the stage Cato was enormously popular in the New World. It was a favorite in the southern colonies in private theatricals, as George Washington remembered on the battlefield during the French and Indian War—as he wrote to the lady who had once been the great love of his life. An inveterate playgoer, Washington had probably seen this drama many times on the professional stage. Some time before 1748 he scribbled verse in his notebook, paraphrasing lines from the play, and his letters during the Revolution contain at least one quotation from it. Long after his presidency he quoted eight lines, including two which were also favorites of his contemporary Landon Carter:

‘When vice prevails, and impious men bear sway,’

The post of honour is a private station [IV, iv, 142–143].

Strolling players had presented Cato professionally in Charleston in 1735 and students of William and Mary produced it in the Williamsburg theater in 1736. It appeared again and again in public performances along the Atlantic coast at Annapolis, Charleston, Baltimore, New York, and Philadelphia, as late as the season 1837–1838. It was quoted in essays in all the southern provincial gazettes, and many political writers used the pseudonym “Cato,” as did Trenchard and Gordon in their famous Letters (soon to be noted). School children in the “Rev. Mr. Warrington’s School” in Elizabeth City parish in Virginia presented the play in 1767 with an original prologue rendered by the rector’s daughter:

If nothing please you else, you’ll clap the zeal

Of brats who pant to serve the common weal.

One must remember too that at St. John’s Church in Richmond Patrick Henry in 1775 echoed five lines of Cato (at least as his biographer William Wirt presents his speech) in the famous peroration ending “give me liberty or give me death.” And it was not by accident that it was one of the two plays presented at Valley Forge during the crucial winter of 1777/1778.

Separately and in the collected Works of Addison, Cato was in southern libraries from Daniel McCarty’s and Robert “King” Carter’s time (before 1724) to at least the mid-nineteenth century. It is advertised for sale, with and without the remainder of Addison’s writings, in the Maryland, Virginia, Carolina, and Georgia gazettes. The Works were owned not only by scores of individuals but also by the Georgia Library Society, the Charleston Library Society, and the Baltimore Library Company. Addison’s plays were recommended for any beginning library in 1771 by Thomas Jefferson. His father had owned them long before.

Almost as popular in the southern colonies was the treatise in novel form by François de Salignac de la Motte Fénelon, archbishop of Cambrai. Les Aventures de Télémaque (1699), and soon in English translation as The Adventures of Telemachus, this “continuation” of the travels of the son of Ulysses in search of a father has of course classical roots. Not meant to be a liberal paper, it is a utopian and fairly easygoing compromise between dreams and possibilities. Its object had originally been to broaden the mind of the heir to the French throne. One feature that attracted Anglo-American libertarians was its advertisement of the doctrine that kings exist for the people rather than the other way around, as Clinton Rossiter has phrased it. By 1759 it had gone through seventeen editions in English. Even some French editions were published in London. But though today it is difficult to see any trace of a belief in liberty of conscience, as ascribed to its author by eighteenth-century readers, perhaps through the familiar process of wishful thinking it was so interpreted. A Scottish-born Virginia tutor in 1769 quoted a long passage from it in French, concerning the eternal punishment of a tyrannical king who had mistreated his slaves, a passage to support this southern colonial’s own strictures on African slavery and miscegenation.

Not later than the 1720s, Télémaque, in English or French, was in all the southern colonies. It was owned by governors of North Carolina and Virginia, by schoolmasters, physicians, lawyers, clergymen (Anglican and dissenting), and planters. Byrd and Jefferson had copies in French, Washington in English. Politician James Milner of North Carolina and a dozen or more Carolina planters possessed French editions. The library companies held copies, and in 1797 the Lunenburg County, Virginia, country store still had it for sale. There are references to it and quotations from it in all the southern newspapers. Yet no one appears to have made a study in depth and breadth as to the reasons for its presence on the bookshelves.

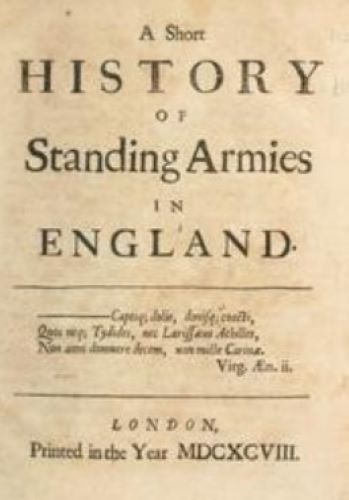

Recent political historians have emphasized the influences of several works by Thomas Gordon and his older collaborator John Trenchard, usually allowing them an impression on eighteenth-century American ideology once assigned to John Locke. Certainly the two series of essays they did together, the Independent Whig and Cato’s Letters (originally appearing in serial form, the former going through seven collected editions from 1721 to 1754 [not counting American issues of 1724 and 1740] and the latter through at least six in the same period), were more frequently found on southern bookshelves than was Locke on government, at least as far as our present knowledge goes. They have been written about extensively by Caroline Robbins, David L. Jacobson, and Bernard Bailyn (among others). Thomas Gordon’s translation of Tacitus (1728), which included “Political Discourses,” was almost as popular and frequently quoted as the two collections of essays. In addition, Gordon translated Sallust in 1744 and Trenchard published A Short History of Standing Armies as early as 1698. Various other works of the two men also appear occasionally in southern libraries.

These libertarian writers and their friends (such as Molesworth) were known as the Independent or Real or Radical Whigs. Their two collections of essays are anticlerical or anti-High Church, adamant against standing armies as instruments of monarchical tyranny, anti-Catholic and anti-Stuart, and concerned with the characters of good and evil magistrates and the nature of human liberty and equality, declaring that governments were instituted by men rather than “revealed” by God, and warning of the dangers of liberty which might lead to tyranny through factions and parties, among other things. Their Whig and Cato spoke vehemently and effectively. The two series owed much to Sidney’s Discourses and earlier republican expressions. Americans found out immediately that these essays could be adapted to their needs, and they were frequently used in the Peter Zenger freedom-of-the-press controversy in New York in the 1730s. Also in New York (somewhat later), the Independent Reflector of William Livingston was patterned in part on the Whig. “The Good Magistrate” in Cato’s Letters No. 37 (quoted from Sidney) appears in the South Carolina Gazette, among other newspapers, in 1736, 1745, and 1749. The Letters were quoted by North Carolinian Maurice Moore in a 1765 pamphlet against taxation of the colonies. George Mason seems to refer to the Letters in a 1766 essay and a 1774 resolution. Both Cato’s Letters and the Whig appear on the shelves of private libraries in every southern colony and are advertised for sale in all their gazettes. They were also in the library societies from 1750 through at least 1798.

Though Thomas Jefferson’s library, sold to Congress in 1814, contained these two collected essays of Trenchard and Gordon, the author of the Declaration appears to have been more interested in Gordon’s translation of Tacitus, with its added political discourses and emphasis on the libertarian nature of German or Saxon government as the Roman historian wrote about it. The original discourses were indeed a distillation of Gordon’s earlier work—for example, in its discussion of the relation of ministers, princes, and peoples; of free and arbitrary governments and the excellency of a limited monarchy; of the revolutionary nature of religion; of freedom of speech and the danger of standing armies. In Jefferson’s opinion, Tacitus was “the first writer in the world without a single exception.” He advised that because of the difficulty of the Latin it should be read with an English translation, and he declared that Gordon, of all translators, had best caught the spirit of the original. His own set of Tacitus was a conflated collection, combining a 1674 Latin printing with the second (1737) edition of Gordon.

In 1733 Stephen Bordley of Maryland wrote to England for a set of Gordon’s first edition of Tacitus, and Daniel Dulany the elder, of the same colony, had this edition in his library. The 1796 library of Edward Lloyd IV also contained Gordon’s translation. In Williamsburg in 1750–1752 Lewis Burwell bought this Tacitus at the Gazette bookshop, and as late as 1806 William Wirt ordered it from a sales catalogue of the Ralph Wormeley library. Georgians and Carolinians had Gordon’s Tacitus, and dozens more in all the southern colonies had Latin versions.

Gradually all the volumes of Gordon and Trenchard disappeared from the southern (and American) bookshelf and were almost forgotten until recent historians searching for American ideological roots rediscovered them. Not only has the almost ubiquitous presence of these books been noted from inventories but we have become conscious of the frequent quotations from them of our eighteenth-century political leaders. The familiar principles of the American revolutionists were probably suggested by or derived from the writings of these men as much as from any other writers of the century.

Almost as well known, as frequently quoted, and as often on bookshelves was Characteristics of Men, Manners, Opinions, Times, etc. by Anthony Ashley Cooper, earl of Shaftesbury, a collection gathered and published by its author in 1711. Its best-known constituent, the previously separately published Inquiry Concerning Virtue (1709), is perhaps to be considered more philosophic, aesthetic, and religious than political, though as usual it is impossible to separate these elements. A Latitudinarian Christian who abhorred Hobbes and had been tutored by John Locke, whom he held in affection and respect, Shaftesbury rejected the mechanistic universe and Locke’s tabula rasa. Admirably tolerant, he defended free-thinkers and was, on the same principle, anti-Puritanical. To find what the mind said, one had to see what the heart said; that is, man has a natural moral sense. The Characteristics as a whole, comments one critic, read like the work of an enraptured deist. Actually, he professed himself a theist. His philosophy, including its optimism, influenced Bolingbroke (next to be considered), the poet James Thomson, the French political theorist Montesquieu, and Americans such as Thomas Jefferson who were perhaps by nature as sanguine as Shaftesbury. His “homespun philosophy” of warning against “enthusiasm” (in our terms “fanaticism”), of declaring that all beauty is truth, of exaltation of nature, and of conviction of the necessity of freedom of thought made him a pioneer figure in all forms of romanticism, including the political. He was not democratical, he was monarchical; but he also advocated free institutions and a general liberalizing of public and private life. A confused and elegant writer, Howard Mumford Jones calls him, but he seems to have struck responsive chords in the minds of southern colonial Americans other than Jefferson, others who owned and quoted his great collection of essays. Like Fénelon and some of the British Real Whigs, he believed that mankind is capable of obtaining, or at least pursuing, happiness in this life.

The Characteristics was owned in every southern province and was frequently offered for sale by local booksellers. Clergymen (including orthodox Anglicans), sheriffs, merchants, and of course dozens of planters, among them William Byrd II, had copies in several volumes. Before 1740, William Dunlop, son of a University of Glasgow professor and owner of a large library that held this work, had a framed portrait (probably a print) of Shaftesbury on his wall, alongside portraits of Bolingbroke and Milton and Sir William Temple. Pre-Revolutionary activists who owned the book were the elder Gadsden, Richard Bland, and James Milner, in three different colonies.

Henry St. John Viscount Bolingbroke, who published Remarks on the History of England (1743) and Letters on the Study and Use of History (1752), is perhaps best remembered for his philosophical essays and especially for his studies in politics. Though he may not seem of first importance today in any of his chosen fields, the major minds—and many others—of his century held his talents in highest regard. Chesterfield and Pope were among them, and in America, Thomas Jefferson declared his style of the highest order, “the finest example in the English language of the eloquence proper for the senate.” He added that Bolingbroke’s political tracts were safe reading for the most timid religionist. These pronouncements from the great democrat may for some reasons seem astonishing, for Bolingbroke was a Jacobite aristocrat who rejected the liberal ideology of Locke’s Second Treatise on Civil Government and Locke’s bourgeois conception of natural right. Yet this British “conservative Whig,” as he has been called, held and widely expressed many ideas with which Jefferson and, even more, John Adams and many southern Revolutionists less liberal than Jefferson or the English Real Whigs might agree. Bolingbroke’s family-centered aristocracy had much in common in theory and practice with the practice and ideas of many southern planters, as did his antagonism to the moneyed interests, the court party, which he felt had replaced the natural rulers, the rural gentry. With southern colonials, he early held the Harringtonian economic-political view, though he replaced it in his Dissertation upon Parties (1735) and Letters on the Spirit of Patriotism; or the Idea of a Patriot King (1749, but available earlier) with concepts that owed something to Machiavelli. This English nobleman was ready to find the principle of party acceptable if that party represented the interests of the whole nation (he felt that the Walpole Whigs represented only one class). His remedy for England’s problems was a patriot king who would be the restorer of a mixed government, in all of which Machiavelli and the cyclical theory of history were involved.

Many of Bolingbroke’s works originally appeared in a periodical, the Craftsman (14 vols, from 1726–1736). Opposed even to the idea of standing armies, he joined—on their far right— the neo-Harringtonians or Real Whigs, aligning himself within limits with these libertarians who had Molesworth and Trenchard and Gordon at their extreme left. His savage attacks in the Craftsman on the Walpole administration were often indistinguishable from the writings of Trenchard and Gordon, and in fact he frequently quoted them. Bailyn has pointed out how close his concept of the English constitution or the idea of a constitution was to John Adams’s, and there were certainly southern delegates to the Constitutional Convention of 1787 who held similar views.

Jefferson, who may not have agreed fully with Bolingbroke on constitutions and certainly not on aristocracy, owned a remarkable number (13) of the Englishman’s writings. He had first editions of Reflections Concerning Innate Moral Principles (1752) and The Philosophical Works (5 vols., 1754); early editions of two volumes of the Craftsman (1727); A Letter to Sir William Windham (1753), which includes a letter to Pope and “Some Reflections on the Present State of the Nation”; A Collection of Political Tracts (1748), including papers from the Craftsman; A Dissertation upon Parties (1754), reprinted separately from 1733–1734 issues of the journal; some editions of the Patriot King (now lost); The Craftsman Extraordinary (1729); The Second Craftsman Extraordinary (1729); Remarks on the History of England (1745), also from the Craftsman; Letters on the Study and Use of History (1752); and another work possibly by St. John. Undoubtedly, Bolingbroke’s influence was strongest on this American’s moral and religious beliefs. William Byrd II had all fourteen volumes of the Craftsman, as did two members of the Custis family. Landon Carter owned at least two of Bolingbroke’s books, and John Mercer had some of his works at Marlborough. Even Mrs. Charles Stagg, widow of the first producer of plays at Williamsburg, owned seven volumes of the Craftsman. In Maryland, Bolingbroke appears in the collections of Stephen Bordley, Charles Carroll of Carrollton, Edward Lloyd IV, and others of lesser note. He also appears several times in North Carolina and often on South Carolina bookshelves, with at least five titles in the Charleston Library Society. Bolingbroke’s combination of an elegant and refreshing style, his appeal to the agrarian or country element of society, and his opposition on many grounds to the British political establishment, which from the 1730s many colonials felt was oppressing them, is the most obvious explanation of his appeal to many southern Americans. Presbyterian clergyman Samuel Davies mentions him in one sermon, but merely to call him an infidel. I have not chanced upon any title by Bolingbroke in any clerical library, Anglican or dissenting.