It was central to the totalitarian transformation of Germany.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The rise of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party in Germany between 1933 and 1945 marked a profound transformation not only of political institutions but also of the judiciary. The Nazi regime’s consolidation of power extended into every sphere of public life, with the legal system being a key target. The judiciary, once rooted in the Weimar Republic’s democratic ideals and constitutional protections, was systematically dismantled and refashioned into an instrument of totalitarian control. This essay explores how Hitler seized and subverted Germany’s judicial apparatus, the ideological and structural transformations that ensued, and the long-term consequences of subordinating the rule of law to authoritarianism.

The Weimar Judiciary: A Vulnerable Institution

The judiciary of the Weimar Republic (1919–1933) was, from its inception, ill-equipped to function as a defender of democratic governance. Inheriting many of its personnel, structures, and norms from the Imperial German legal system, the judiciary remained deeply conservative and monarchist in orientation. Judges were predominantly drawn from the old elite—largely aristocratic, Protestant, and nationalist in sentiment—many of whom viewed the Republic with suspicion, if not outright disdain. These judges had been trained under an autocratic regime and now found themselves serving a parliamentary democracy they neither trusted nor ideologically supported. As a result, the judiciary was often hostile to the Republic’s political left and lenient toward right-wing extremists, a double standard that would prove fatal in undermining democratic resilience.1

This ideological imbalance was reflected in several key judicial decisions during the early 1920s. The courts treated acts of leftist violence with severity, while perpetrators of right-wing violence often received mild sentences or were acquitted altogether. A notorious example is the 1922 assassination of Foreign Minister Walther Rathenau, a Jew and liberal democrat, by right-wing extremists. Although the murder was politically motivated and destabilizing, the courts refrained from framing it as a treasonous act.2 In contrast, leftist agitators and communists were frequently prosecuted under emergency decrees and received harsher penalties, even when their actions were less severe. This asymmetry fostered an environment in which paramilitary groups such as the Freikorps and, later, the Nazi SA operated with near impunity, emboldened by a judiciary unwilling to challenge them.

Structurally, the Weimar judiciary also suffered from constitutional ambiguities and loopholes that could be—and eventually were—exploited. Chief among these was Article 48 of the Weimar Constitution, which granted the president emergency powers to rule by decree during times of crisis. While this clause was originally intended as a safeguard, it became a tool for undermining parliamentary authority and bypassing judicial review. Presidents Friedrich Ebert and later Paul von Hindenburg invoked Article 48 dozens of times throughout the Republic’s existence, gradually normalizing authoritarian governance within a formally democratic framework.3 The judiciary rarely challenged these actions, setting a dangerous precedent that facilitated Adolf Hitler’s legal ascent to dictatorial power in 1933.

Judicial independence in the Weimar era was also compromised by a broader societal climate that prioritized stability and order over democratic principles. Many jurists and legal theorists openly criticized the “excesses” of democracy and called for a more authoritarian state structure. The legal academy was not immune to this trend; figures like Carl Schmitt, though not a judge, wielded significant influence in shaping conservative legal thought that emphasized the necessity of a strong state and downplayed the value of individual rights.4 In such a climate, the judiciary’s function increasingly became one of legitimizing authoritarian measures rather than safeguarding constitutional protections. By the late 1920s, even before the Nazi seizure of power, the judiciary had already begun to drift away from democratic norms.

The failure of the Weimar judiciary to adapt to the demands of democratic governance was not merely a matter of institutional inertia but reflected a deeper cultural and ideological continuity with the Imperial past. This continuity rendered the judiciary vulnerable to co-optation when the Nazis rose to power. Judges who had already demonstrated a willingness to prioritize nationalistic and conservative values over the rule of law found little difficulty in aligning with Nazi legal ideology. Thus, when Hitler moved to dismantle democratic institutions, he encountered a judiciary not prepared to resist but predisposed to cooperate.5 The collapse of judicial independence in 1933, then, was not a sudden rupture but the culmination of a slow erosion rooted in the Republic’s foundational weaknesses.

The Legal Revolution: Hitler’s Early Moves

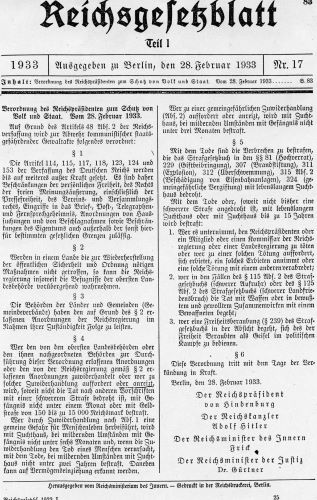

Adolf Hitler’s path to absolute control over Germany did not begin with overt dictatorship, but rather with calculated legal maneuvers that exploited the weaknesses of the Weimar Constitution and manipulated the existing judiciary. Upon his appointment as Chancellor on January 30, 1933, Hitler lacked the full legal authority to reshape the state in his image. However, he moved rapidly to erode democratic norms through legislative and executive action. One of the most significant initial steps was the Reichstag Fire Decree of February 28, 1933, officially titled the Decree for the Protection of People and State. This decree suspended core civil liberties guaranteed by the Weimar Constitution, including freedom of speech, assembly, and protection from arbitrary arrest.6 It allowed the Nazi regime to detain political opponents—primarily Communists—without judicial review, effectively rendering the courts powerless in political cases from the outset of Hitler’s chancellorship.

The Enabling Act, passed on March 23, 1933, represented a further and more profound erosion of judicial oversight. Officially known as the Law to Remedy the Distress of the People and the Reich, this act granted Hitler and his cabinet the authority to enact laws without the involvement of the Reichstag or the President, even if such laws contravened the constitution.7 In securing the passage of the Enabling Act, Hitler used intimidation, arrests, and backroom deals—most notably with the Catholic Centre Party—to obtain the two-thirds majority needed. While this legislation primarily affected legislative power, its implications for the judiciary were immense. It placed the executive branch above all constitutional limits and allowed for the rapid Nazification of German law. Judges were now expected not merely to interpret the law but to apply decrees crafted by Hitler’s cabinet that reflected Nazi ideology.

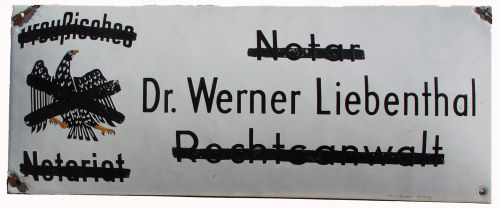

Simultaneously, the purge and restructuring of the judicial system began in earnest. The Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service, enacted on April 7, 1933, was the primary tool used to remove individuals considered politically unreliable or racially undesirable.8 Judges and legal officials who were Jewish, Social Democratic, or otherwise viewed as unsympathetic to the regime were dismissed. This not only eliminated opposition but also instilled fear and conformity among those who remained. Franz Gürtner, the Minister of Justice and a conservative nationalist, attempted to mediate between traditional legality and Hitler’s demands, but he ultimately facilitated the erosion of judicial independence by allowing ideological loyalty to take precedence over legal professionalism.9 The result was a judiciary that, by late 1933, had begun to view its primary function as safeguarding the Nazi state rather than upholding the rule of law.

In addition to purging personnel, Hitler created parallel judicial structures that operated outside the bounds of traditional legal norms. The regime established Sondergerichte (special courts) to handle politically sensitive cases and sidestep what remained of judicial procedure. These courts had no appeals process and rendered verdicts aligned with Nazi interests.10 In 1934, the infamous Volksgerichtshof (People’s Court) was created following the botched investigation into the Reichstag Fire and subsequent show trials. This court became the principal organ for the repression of political dissent and was notorious for its swift and brutal judgments. Under Roland Freisler’s leadership, it turned trials into propaganda spectacles and wielded the death penalty with devastating frequency. The proliferation of these extrajudicial institutions further weakened the standing of the traditional judiciary, now seen as redundant unless compliant with Nazi aims.

Beyond the structural changes, Hitler also launched an ideological campaign to redefine the judiciary’s role. The Nazi regime promoted the concept of Volksgemeinschaft—a racially unified national community—and demanded that legal professionals align with it in both spirit and action. Judges were encouraged to practice Gesinnungsjustiz (justice according to ideological sentiment), whereby loyalty to the Führer and the racial mission of the state outweighed legal codes or constitutional principles.11 Legal education was overhauled to indoctrinate future judges in National Socialist principles, while legal organizations like the National Socialist League of German Jurists ensured that career advancement was contingent on party loyalty. In this context, judicial independence was not simply suppressed—it was rendered obsolete. The court system became a mechanism for enforcing ideological conformity, and Hitler’s early legal manipulations ensured that no avenue of resistance remained within the judiciary.

Purging and Restructuring the Courts

Once the Enabling Act had secured Hitler’s legislative dominance, one of the regime’s highest priorities was transforming the judiciary into a loyal servant of the Nazi state. Central to this process was a sweeping purge of judges and court personnel who were deemed politically unreliable, racially undesirable, or ideologically incompatible with National Socialism. The key legal instrument was the aforementioned Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service (April 7, 1933), which allowed for the dismissal of civil servants—including judges—on political or racial grounds. This law especially targeted Jewish jurists and those affiliated with leftist or democratic movements.12 While presented as an administrative reform, the law was a calculated political purge designed to create a homogeneous legal corps that would not challenge Nazi policies.

This purge extended to all levels of the judiciary, from the Reich Court (Reichsgericht) to local magistrates. Those removed were not just dismissed but often publicly humiliated or subjected to surveillance, contributing to a broader atmosphere of fear within the legal community. Even judges who had no party affiliation but remained committed to Weimar legal norms were scrutinized and sidelined.13 Those who remained were either ideologically aligned with Nazism or willing to conform to avoid professional ruin. The newly politicized nature of the courts was made unmistakably clear when legal organizations such as the German Bar Association (Deutscher Anwaltverein) and the Association of German Judges (Deutscher Richterbund) were absorbed into the National Socialist League of German Jurists (NSRB). This professional restructuring ensured that advancement, security, and influence in the judiciary depended on loyalty to Hitler.

The Nazi regime also undertook structural reforms to align court administration with its broader authoritarian project. The Ministry of Justice, under Franz Gürtner, became a tool for enforcing ideological conformity rather than legal impartiality. Although Gürtner was not a Nazi Party member, he facilitated the regime’s objectives by providing a veneer of legal legitimacy. He ensured that courts handed down judgments consistent with Nazi ideology and often intervened to revise verdicts that were considered too lenient toward political enemies.14 Gürtner helped integrate existing court structures with the newly created political courts, such as the Sondergerichte (Special Courts), which were staffed by judges selected for their ideological reliability. These courts operated with curtailed procedural protections and focused on so-called “enemies of the state,” especially Communists, Jews, and dissidents.

The judicial reforms were not simply about purging or intimidating individual judges—they were part of a conscious effort to redefine the very purpose of justice in the Third Reich. Under Nazi legal theory, the courts were not impartial arbiters of law, but agents of the Volksgemeinschaft, or racial national community. This ideological framework positioned the judiciary as a vehicle for protecting the Aryan people and the German state rather than upholding universal principles of justice or due process. Legal decisions were expected to reflect National Socialist morality, and laws were interpreted in terms of their alignment with the will of the Führer.15 The traditional idea of jurisprudence as a neutral system of rules was discarded in favor of a racialized, politicized vision of justice.

As this transformation accelerated, courtrooms became sites of both repression and propaganda. The establishment of the Volksgerichtshof (People’s Court) in 1934 after the Night of the Long Knives signaled the final death knell of independent justice in Germany. Headed by the fanatical Roland Freisler after 1942, this court was infamous for its performative trials and brutal sentencing, particularly during the war years. Defendants were routinely denied meaningful legal representation, and trials were designed to reinforce Nazi ideology to the public.16 The spectacle of “justice” became a means to frighten opposition and reinforce the state’s moral authority. By the mid-1930s, the court system, once a potential check on executive power, had become an active participant in the Nazi regime’s machinery of terror and racial persecution.

Legal Ideology and Nazi Jurisprudence

The Nazi transformation of the German legal system was not merely administrative or procedural—it was fundamentally ideological. Nazi jurisprudence redefined the law as an instrument of the Volksgemeinschaft (people’s community), subordinating all legal norms to the racial and political goals of the regime. Hitler himself rejected the notion of objective law in favor of a dynamic legal system rooted in the Volkswille—the will of the people as embodied by the Führer.17 This principle meant that law was not a static set of rules but an evolving expression of the Nazi worldview. Accordingly, legal certainty and formal equality before the law, hallmarks of liberal jurisprudence, were replaced by a racialized and political conception of justice in which the rights of the individual could be suspended or eliminated for the sake of the community.

Central to this ideological shift was the emergence of a new class of jurists and legal theorists who justified and articulated the Nazi legal order. Among the most prominent was Carl Schmitt, often referred to as the “Crown Jurist of the Third Reich.” Schmitt provided intellectual cover for Hitler’s actions, arguing that sovereignty lay in the power to declare the state of exception—that is, to suspend the law in order to protect it.18 Schmitt’s theories legitimized Hitler’s extralegal moves following the Reichstag Fire and laid the foundation for a jurisprudence based on the Führerprinzip, the idea that Hitler’s will constituted the highest legal authority. Other Nazi legal scholars embraced Gesinnungsjustiz, or justice based on ideological conviction, which replaced objective legal reasoning with political loyalty and intuition about what served the racial interests of the German people.

Legal institutions were swiftly reshaped to reflect this ideological transformation. Judges and lawyers were not only encouraged but expected to issue decisions and legal opinions in line with National Socialist values, even in the absence of specific laws. Judicial discretion became a tool of ideological enforcement, allowing judges to interpret the “healthy sentiment of the people” (gesundes Volksempfinden) as a legitimate legal standard.19 This subjective measure of popular morality allowed for broad and often arbitrary punishments, particularly against those deemed enemies of the state—Jews, Roma, political dissidents, and others. The erosion of formal legal constraints thus created a fluid legal environment where repression could be justified retroactively, and state violence could be legalized through reinterpretation.

Education and professional training were crucial instruments in embedding Nazi legal ideology. Law schools were restructured to promote racial theory, loyalty to the Führer, and the subordination of law to state goals. Academic freedom was curtailed, and professors who resisted were dismissed or silenced. Textbooks and curricula were revised to reflect Nazi doctrine, emphasizing the role of law in constructing and preserving racial purity.20 The National Socialist League of German Jurists oversaw the ideological screening of legal professionals and ensured conformity within the legal system. These measures produced a generation of lawyers and judges indoctrinated in the belief that legal legitimacy derived not from codified statutes or constitutional principles but from their alignment with National Socialist ideology.

Nazi jurisprudence represented the antithesis of the rule of law. It fused law and politics into a unified system in which justice was defined by loyalty to the regime and its racial mission. The individual no longer had inherent rights but existed only in relation to their perceived value to the racial community.21 This ideological redefinition of legality enabled the legal system to become a willing and active participant in the Holocaust and other crimes of the Third Reich. Judges and prosecutors did not merely comply with orders—they embraced a worldview in which mass violence could be justified as the highest form of legal duty. In doing so, the legal profession was thoroughly complicit in the Nazi state’s descent into barbarism.

The Role of Judges and Legal Professionals

In the transformation of the German legal system under the Third Reich, judges and legal professionals played an active, rather than merely complicit, role. Far from being neutral arbiters of justice reluctantly swept up in a political maelstrom, many members of the judiciary eagerly aligned themselves with Nazi ideology, enforcing policies of exclusion, repression, and persecution. Judges, in particular, viewed the collapse of the Weimar Republic and the rise of Hitler as an opportunity to restore order, discipline, and national unity—values they believed had been undermined by democratic liberalism.22 The legal profession’s traditional conservatism, coupled with deep-rooted authoritarian leanings and antisemitic prejudice, made many in the judiciary predisposed to support the new regime.

Following the purge of politically and racially “unreliable” legal personnel, those who remained demonstrated remarkable ideological flexibility. They interpreted vague or broadly worded Nazi laws in ways that maximized their punitive potential and sought to align their rulings with the regime’s priorities—even when no explicit directives had been issued. Judges would often exceed the demands of prosecutors in delivering harsh sentences against so-called enemies of the state.23 For instance, in political trials under the Sondergerichte (Special Courts), defendants were frequently convicted on flimsy evidence or for offenses that were effectively political dissent. In such courts, the presumption of innocence was virtually eliminated, and due process was irrelevant. This behavior reflected not just coercion or fear but a broader professional ethos that accepted, and even internalized, Nazi values.

Legal professionals also served a crucial function in giving Nazi policies an appearance of legitimacy. Rather than abandoning legal formality altogether, the regime often pursued its radical agenda through quasi-legal means. Lawyers drafted the decrees and statutes that underpinned racial laws such as the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, which systematized the exclusion of Jews from civil society and codified racial hierarchy.24 Jurists lent their expertise to the process of bureaucratic genocide, ensuring that administrative actions—from property confiscations to deportations—were framed in legal language. This use of law as a tool of oppression reinforced the idea that the Nazi state operated under a rational, rule-based system, even as it committed atrocities. Thus, the legal profession was not a passive instrument but an intellectual engine for tyranny.

Perhaps most disturbingly, judges were instrumental in normalizing the use of state violence. This was particularly evident in the actions of the Volksgerichtshof (People’s Court), where trials for treason and sabotage—especially after the July 20, 1944, plot—became orchestrated performances culminating in death sentences.25 Roland Freisler, the court’s notorious president, used trials as propaganda spectacles to berate, humiliate, and condemn defendants in a fashion more suited to a show trial than a court of law. But Freisler was not an aberration—his behavior was the logical culmination of a system in which judges were expected not only to convict but to embody Nazi ideology in the courtroom. Those unwilling to do so often remained silent, complicit through their failure to resist or resign.

The complicity of legal professionals in Nazi Germany underscores a critical lesson: authoritarian regimes do not necessarily destroy legal institutions; they co-opt them. The judiciary under Hitler was not eliminated but reshaped to serve the regime’s goals. Judges and lawyers retained their prestige, titles, and procedures, but they redefined their professional ethics to prioritize loyalty to the state over justice or truth.26 Their cooperation made the Nazi dictatorship more efficient and more dangerous, cloaking its crimes in legal respectability. This transformation illustrates the moral peril inherent in a legal culture that values obedience and order above human rights and ethical accountability.

Consequences and Legacy

The consolidation of the judicial system under Hitler had immediate and catastrophic consequences for the rule of law in Germany. By transforming the judiciary into a political instrument, the Nazis effectively dismantled the checks and balances that typically restrain executive power. Legal institutions, once tasked with safeguarding individual rights and due process, became complicit in widespread persecution, dispossession, and eventually, genocide.27 The courts legitimized arbitrary arrests, legalized discriminatory laws such as the Nuremberg Laws, and approved expropriations of Jewish property. This erosion of judicial independence also signaled to the public that justice was no longer blind but would now serve the racial and ideological aims of the regime. As a result, trust in the legal system as a source of fairness and equity collapsed, replaced by fear, silence, and conformity.

One of the most significant outcomes of Hitler’s judicial overhaul was the institutionalization of state terror. The judiciary enabled the consolidation of the Gestapo’s powers, allowing extrajudicial detention in “protective custody” without trial.28 Legal professionals either supported this practice or failed to challenge it, providing a veneer of legality for the regime’s repressive tactics. The creation of Special Courts (Sondergerichte) and the People’s Court (Volksgerichtshof) further entrenched this system, ensuring that political trials became public performances aimed at deterrence and humiliation. These tribunals issued thousands of death sentences, often for minor offenses or acts of dissent, and demonstrated how a corrupted legal system could be wielded to crush opposition with chilling efficiency.

The long-term legacy of Nazi legal consolidation reverberated well beyond 1945. After the war, the Allied occupation authorities faced the immense task of denazifying the German legal profession. However, efforts to purge the judiciary of its Nazi past were uneven and incomplete.29 Many former Nazi judges and prosecutors resumed their careers in West Germany, protected by the argument that they had simply enforced the law of the time. This continuity hindered full accountability and delayed critical reflection on the judiciary’s complicity. It also contributed to a sense of impunity, particularly regarding mid- and lower-level legal professionals who had actively supported the regime’s crimes but were never prosecuted. The persistence of this legacy challenged the legitimacy of postwar justice and revealed the depth of institutional entrenchment created under Hitler.

Nonetheless, the experience of Nazi legal collapse spurred important developments in legal and constitutional thinking in the postwar era. In the Federal Republic of Germany, the 1949 Basic Law (Grundgesetz) included robust protections for judicial independence, human dignity, and individual rights—principles explicitly designed to prevent a return to totalitarianism.30 Courts such as the Federal Constitutional Court (Bundesverfassungsgericht) were given a central role in upholding democratic norms and reviewing legislation. Similarly, international law was profoundly shaped by the revelations of legal perversion under the Nazis. The Nuremberg Trials established the precedent that “following orders” was not a defense for war crimes, and that jurists could be held accountable for implementing unjust laws. These lessons helped shape postwar human rights frameworks and war crime statutes.

Hitler’s consolidation of the judicial system offers a stark warning about the fragility of legal institutions in the face of authoritarianism. It demonstrates that even well-established systems of law can be hollowed out when legal actors abandon their ethical responsibilities.31 The transformation of the judiciary into a tool of ideological repression did not require the dismantling of the courts but rather their redirection by loyal and willing professionals. The legacy of Nazi jurisprudence reminds us that the law is only as just as those who interpret and enforce it—and that the preservation of democracy depends not only on legal structures, but also on the moral courage of the people within them.

Conclusion

Hitler’s takeover of the judiciary was not a peripheral aspect of his regime—it was central to the totalitarian transformation of Germany. By reshaping the legal system to serve the Führer’s will, the Nazis destroyed the concept of impartial justice and subordinated the law to ideology. The complicity of judges and legal professionals highlights the vulnerability of legal institutions in the face of authoritarianism. The lesson of Nazi Germany is that the rule of law is not self-sustaining—it must be defended not only through legal mechanisms but by the moral courage of those entrusted to uphold it.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Richard J. Evans, The Coming of the Third Reich (New York: Penguin Press, 2003), 39–41.

- Hans Mommsen, The Rise and Fall of Weimar Democracy, trans. Elborg Forster and Larry Eugene Jones (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996), 224–25.

- Detlev J. K. Peukert, The Weimar Republic: The Crisis of Classical Modernity, trans. Richard Deveson (New York: Hill and Wang, 1992), 52–54.

- Carl Schmitt, Political Theology: Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty, trans. George Schwab (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005), 5–7.

- Jan-Werner Müller, Contesting Democracy: Political Ideas in Twentieth-Century Europe (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011), 94–96.

- Evans, The Coming of the Third Reich, 340-343.

- Hans Mommsen, The Rise and Fall of Weimar Democracy, trans. Elborg Forster and Larry Eugene Jones (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996), 380–82.

- Peukert, The Weimar Republic, 265.

- Ingo Müller, Hitler’s Justice: The Courts of the Third Reich, trans. Deborah Lucas Schneider (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991), 54–58.

- William Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1960), 281–83.

- Müller, Contesting Democracy, 98-100.

- Müller, Hitler’s Justice, 56-58.

- Richard J. Evans, The Third Reich in Power (New York: Penguin Press, 2005), 77–80.

- Mommsen, The Rise and Fall of Weimar Democracy, 387-390.

- Michael Stolleis, The Law Under the Swastika: Studies on Legal History in Nazi Germany, trans. Thomas Dunlap (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 45–48.

- Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, 352-354.

- Claudia Koonz, The Nazi Conscience (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2003), 40–43.

- Schmitt, Political Theology, 5-15.

- Müller, Hitler’s Justice, 67-70.

- Stolleis, The Law Under the Swastika, 75-77.

- Evans, The Third Reich in Power, 251-253.

- Müller, Hitler’s Justice, 9-13.

- Evans, The Third Reich in Power, 78-80.

- Stolleis, The Law Under the Swastika, 85-89.

- Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, 1090-1093.

- Koonz, The Nazi Conscience, 159-161.

- Müller, Hitler’s Justice, 170-172.

- Evans, The Third Reich in Power, 105-107.

- Rebecca Wittmann, Beyond Justice: The Auschwitz Trial (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2005), 39–43.

- Donald P. Kommers and Russell A. Miller, The Constitutional Jurisprudence of the Federal Republic of Germany (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012), 34–36.

- Stolleis, The Law Under the Swastika, 167-170.

Bibliography

- Evans, Richard J. The Coming of the Third Reich. New York: Penguin Press, 2003.

- The Third Reich in Power. New York: Penguin Press, 2005.

- Kommers, Donald P., and Russell A. Miller. The Constitutional Jurisprudence of the Federal Republic of Germany. Durham: Duke University Press, 2012.

- Koonz, Claudia. The Nazi Conscience. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2003.

- Mommsen, Hans. The Rise and Fall of Weimar Democracy. Translated by Elborg Forster and Larry Eugene Jones. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

- Müller, Ingo. Hitler’s Justice: The Courts of the Third Reich. Translated by Deborah Lucas Schneider. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991.

- Müller, Jan-Werner. Contesting Democracy: Political Ideas in Twentieth-Century Europe. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011.

- Peukert, Detlev J. K. The Weimar Republic: The Crisis of Classical Modernity. Translated by Richard Deveson. New York: Hill and Wang, 1992.

- Schmitt, Carl. Political Theology: Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty. Translated by George Schwab. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

- Shirer, William. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1960.

- Stolleis, Michael. The Law Under the Swastika: Studies on Legal History in Nazi Germany. Translated by Thomas Dunlap. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998.

- Wittmann, Rebecca. Beyond Justice: The Auschwitz Trial. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2005.

Originally published by Brewminate, 06.10.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.