Saints are not truly saints until they are dead.

By Dr. Blake Gutt

Postdoctoral Scholar

Institute for Research on Women and Gender (IRWG)

University of Michigan

Abstract

This chapter explores the ways that sacred, physically impaired, and transgender embodiment(s) are all structured by reference to notions of wholeness, perfection, and cure. Focusing on the character of Blanchandin·e in the fourteenth-century French narrative, Tristande Nanteuil, the analysis considers how disability, cure, and gender trans-formation are employed to modify a body according to the exigencies of the surrounding hagiographic narrative. Blanchandin·e’s physical form is repeatedly altered in response to the needs of their son, St Gilles. The chapter traces the shared effects and affects of the social formation – and disassembly – of trans-ness, sanctity, and physical impairment through the related, connected, and leaky bodies of Blanchandin·e and St Gilles.

Introduction

Saints are not truly saints until they are dead. As Brigitte Cazelles writes, ‘the death of the saint is […] the first stage of the hagiographic phenomenon […]. Interest in the dead person ignites the desire to know more about their life’.1 A saintly death simultaneously produces and confirms saintly identity. The perfection associated with sanctity thus draws on a notion of completeness: the saint’s life is over; we can tell the whole story. We can be sure that this individual is a saint, since they are not alive to fall from grace through a human act. We can possess them completely – in memory, in narrative, and in relic form. Yet the phenomenon of sanctity simultaneously troubles any notion of completeness. Saints do not only exist in the past: their continued presence, bridging earth and heaven, is what makes them valuable as intercessors.2 The narratives that relate their lives are multiple and variable, and fluid enough to cross generic boundaries. And holy relics, in the words of Caroline Walker Bynum, offer completeness ‘either through reunion of parts into a whole or through assertion of part as part to be the whole’.3 This equivocal and protean relationship to completeness marks and shapes saints’ embodiment, as well as their disembodiment.4

In this essay, I explore the ways that perceptions of sacred, disabled, and transgender embodiment(s) are structured by reference to similar notions of wholeness, perfection, and cure. ‘Disability’, of course, is a broad umbrella term. In this analysis I specifically address physical impairment, as I examine how disability and gender transformation are employed to modify the body of a literary character (Tristan de Nanteuil’s Blanchandin·e) according to the exigencies of the surrounding hagiographic narrative. I use the terms ‘impairment’ and ‘disability’ interchangeably, following Alison Kafer’s political/relational model of disability. Kafer’s model undoes the rigid distinction that the social model draws between ‘impairment’ and ‘disability’, recognizing that both of these categories – the ‘physical or mental limitation[s]’ that the social model refers to as ‘impairments’, and ‘the social exclusions based on, and social meanings attributed to’ those impairments (which the social model defines as ‘disability’) – are in fact social constructs, dependent upon ‘economic and geographic [and, I would add, temporal] context’.5 My case study, the character of Blanchandin·e in the anonymous fourteenth-century French text Tristan de Nanteuil, vividly demonstrates the imbrications of sacred, transgender, and disabled embodiments. Blanchandin·e’s body is transformed from female to male, and impaired by the loss of a limb before being cured through a miracle. These physical changes chart the entwined bodily destinies of Blanchandin·e and their son, St Gilles. To fully analyse the patterning of this narrative, it is necessary first to consider the interwoven theoretical constructions of these embodiments.

Sacred, Disabled, and Transgender Bodyminds

‘Disability’ is only comprehensible through reference to the supposed norm of ‘ability’. Thus, the disabled bodymind is frequently perceived as doubled, haunted by the ‘perfect’ or ‘complete’ bodymind which is deemed to be absent when the disabled bodymind is present.6 Likewise, transgender embodiment is perpetually at risk of being read either as an incomplete or imperfect imitation of cisgender embodiment (i.e. a trans man can never access the authentic masculinity of a cis man), or as a degraded form of a previously perfect embodiment (i.e. a trans man has corrupted his embodiment by ‘refusing’ to conform to the norms of cis womanhood). Such flickering doubles of trans and disabled subjects lurk in the mind’s eye of the beholder. The social order dreams of cure for both disabled subjects (‘repairing’ or replacing the bodymind) and trans subjects (a becoming-cis which is either curative or violently ‘restorative’). Both transgender and physically impaired embodiments are non-normative, according to social rules, patterns and structures. As such, these embodiments are never free of context; transgender identity and disability are community effects, and produce community affects. Sacred embodiment, too, is a collective embodiment, since it represents salvation not only for the saint but for those who surround them.7 Sacred embodiment is a paradoxical notion, since to be a saint is progressively to abandon materiality, including the body itself, in a translation into the spiritual that is completed by death. Yet it is always through and by the body that sanctity is achieved. A body is required, so that it can be disdained – its flesh chastised, nourishment refused – or so that it can be inhabited with an intensity that expands bodily possibilities. Excessive saintly forms display uncanny abilities such as levitation, or the miraculous healing of other bodies. The discarding of the body at the moment of death figures a transition beyond the material, yet even post mortem the body of a saint has work to do: remaining incorrupt, emitting sweet odours and, in the form of relics, performing intercessory and healing functions. Thus, although the metaphysical existence of saints is what ultimately affirms their sanctity, sacred bodies remain essential. The varied meanings of these bodies are determined though social interactions.

All bodies are subject to intense and complex socio-cultural mediation. For the unmarked subject, this mediation is smooth and silent, enabling the fantasy of direct, automatic, and natural being-in-the-world. For marked subjects, such as trans people and physically impaired people, these processes of mediation are rendered painfully clear through socio-cultural discourse(s) that invoke normative modes and models of existence. Disabled and transgender individuals’ own relationships to and understanding of their bodies are afforded less significance and validity than dominant notions of physical (ab)normality. Whereas saints’ bodies are frequently de-emphasized, the bodies of trans and physically impaired people are typically over-emphasized. Both of the latter groups are routinely reduced to their bodily topography, and specifically to its differences from the (cis, able-bodyminded) norm; the effect is multiplied for individuals who are both disabled and trans.8 Similarly, the meaning of the saintly body is produced by, and shared out among, a community, since the saintly body signifies through and for others. Alicia Spencer-Hall describes this function of sacred embodiment in the case of the thirteenth-century Cistercian nun known as Alice the Leper as follows:

Alice’s leprosy is a boon for her community, and a means for them to expurgate sin: She bears their spiritual wounds in somatized form, and there is little space for Alice’s own experiences. Alice is a gap – or wound – in the tissue of her community, rather than a subject proper.9

Alice’s sanctity and her disability signify simultaneously: the illness that progressively impairs her body is both a mark of divine love and a mechanism for taking on the sins of her peers. Through each of these aspects of her leprous embodiment, her piety and her spiritual status are enhanced.10

Linking Bodyminds

Alice’s example demonstrates how sacred embodiment functions both to reinforce normative embodiment (the holy body marks the boundaries of physical normativity), and to indicate the potential for transcendence (the boundaries are marked by means of their transgression). Thus, sacred embodiments constitute what I refer to as an ‘included outside’: a section of a system which marks the edges of that system; which, while nominally included, makes manifest what is beyond and outside the system’s scope. Holy bodies are at once alluring and terrifying. This contradiction, I suggest, is part of the mechanism that ensures that saints remain rare, extraordinary. Normate subjects inhabit the centre of the system, and the abjection of the included outside delineates borders which cannot safely be crossed. For non-normate subjects, however, the logic of sanctity reveals liberating individual, spiritual, and social relationships to the body, relationships that resist mainstream cultural expectations. The model of sacred embodiment offers a way of understanding and experiencing bodies that defy norms not as abject but as productive – both of metaphysical signification and of earthly community ties. I argue that medieval literature depicts sacred, impaired, and transgender embodiments in similar ways. Modern ableism casts disability as ‘inherently negative, ontologically intolerable and in the end, a dispensable remnant’.11 Medieval texts, however, of fer myriad ways to read disability of all kinds – physical, intellectual and sensory; acquired and congenital; chronic illness and chronic pain – as meaningful, productive, valuable, and above all, connective, linking earthbound bodies to each other, but also to the divine.12 These readings resonate profoundly with modern crip theory, whose structures in turn draw on queer theory. As Robert McRuer argues, able-bodied identity is a fantasized state which, like cisheterosexuality in Judith Butler’s analysis, must be repeatedly imitated in order to give the impression that it exists as a stable referent.13

McRuer indicates that compulsory cisheterosexuality and compulsory able-bodymindedness are fundamentally intertwined. He writes:

Able-bodied identity and heterosexual identity are linked in their mutual impossibility and in their mutual incomprehensibility – they are incomprehensible in that each is an identity that is simultaneously the ground on which all identities supposedly rest and an impressive achievement that is always deferred and thus never really guaranteed.14

The very impossibility and unknowability of both able-bodyminded embodiment and cisheterosexual embodiment reveals them as socio-cultural imaginings. Thus, the cultural production of both disabled and transgender bodies fortifies the supremacy of normate embodiment. Non-normate embodiment is always constructed through socio-cultural norms, such that even the individuals who inhabit these bodies are constrained to an indirect relation to their physical selves, a contact refracted through ambient concepts of ‘correct’ and normative embodiment. The force of this knowledge regime is intensified via the inevitable internalization of ableism and transphobia. As a result, trans and disabled individuals’ knowledge of and authority over our own bodies is delegitimized. However, the sharing of bodily effects and affects among individuals indicates a pathway for another kind of communal production of meaning, and the construction of networks centred on the reclaiming of non-normate embodiments and identities.

The link between sacred bodies and trans bodies is well attested in medieval Western Christianity. From the writings of major figures in the church, to hagiography, mysticism, and extra-canonical genres such as hagiographic romance, non-normatively gendered embodiments frequently signify a privileged relationship to the divine. Better-known examples include the corpus of ‘transvestite monk’ narratives, in which individuals assigned female at birth live as monks and ultimately become saints, and the popularity of maternal imagery in descriptions of God and Christ among twelfth-century Cistercian monks.15 Many medieval hagiographic texts also assume that disability needs sanctity, so that miracles can be per-formed, and impairments can be removed. This in turn means that sanctity needs disability as its object, or its substrate: a saint cannot demonstrate sanctity through miraculous healings if there is no one to heal.16 Saints, too, frequently experience illness, pain, or impairment. These events are presented as establishing or affirming contact with the divine, and as giving rise to specific kinds of embodied and situated knowledge, dependent on and produced through disability: cripistemologies.17 I argue that this constellation of bodies and social formations – transgender, physically impaired and sacred embodiments – coheres because of the similarity of the structuring logics, meaning that the individual elements will often be found in conjunction.

Blanchandin·e’s Bodymind

I now turn to my case study, the character of Blanchandin·e in Tristan de Nanteuil, an anonymous fourteenth-century French chanson d’aventures.18 The text, which is preserved in a single manuscript, is made up of 480 monorhyming laisses, or variable-length stanzas, comprising a total of 23,361 lines.19 The complex narrative of this vast work incorporates a version of the life of St Gilles, the patron saint of people living with permanent physical impairments, such as absent limbs or limited mobility, and of beggars.20 The body of Blanchandin·e, Gilles’ parent, is demonstrably malleable, and can be altered to serve Gilles’ needs. Blanchandin·e, who might be considered a quasi-saint themself, experiences a complex trajectory of physical transformation in the course of the narrative. They are first known as Blanchandine, and later as Blanchandin (the feminine and masculine forms, respectively, of the same name). The original French employs the pronouns ‘she’ (‘elle’) for Blanchandine, and ‘he’ (‘il’) for Blanchandin. I follow this usage when discussing specific moments in the character’s life; however, I also strategically refer to the character using the compound form ‘Blanchandin·e’, and singular they/them pronouns, in order to emphasize the unity of the character’s identity despite changes to their embodiment.

When we first meet Blanchandine, she is a Muslim princess; she subsequently converts to Christianity, and becomes the first wife of the eponymous Tristan de Nanteuil. The couple have a son, Raimon, and three years later Blanchandine encounters an angel who transforms her into a man. The transformation follows a period of male disguise intended to protect her identity while Tristan and Blanchandine are in hiding from the latter’s vengeful father. Though it may be tempting to read the time Blanchandine spends in male dress, and using the name Blanchandin, as a social transition, I have argued elsewhere that this interpretation of the text does not withstand scrutiny.21 The ‘Blanchandin’ disguise is just that; it is not until the moment of physical transformation that Blanchandine becomes Blanchandin. For this reason, my focus in this chapter is on embodiment rather than identity. Modern discussion of ‘identifying as’ and ‘identified gender’ often seems to separate being from identifying (as).22 Thus transness is held at a remove from being; an apparently structured (or constructed) transgender existence is opposed to the supposed immediacy and naturalness of cisgender existence. An exploration of the depiction of transgender embodiment in Tristan de Nanteuil allows consideration of transgender status as a reality produced by sociocultural interactions in the same way as cisgender status. My analysis returns to the physicality of trans embodiment not to reinscribe shallow notions of the ‘wrong’ body, but rather to consider how transgender being, like cisgender being, is always produced through the body, its affects, and its relations and orientations to other bodies. This is true in the case of transformation narratives such as Tristan de Nanteuil, but also in cases where trans embodiment is produced through and by bodily techniques and technologies ranging from medical interventions and prostheses, to dress and grooming choices, to social performances and interactions.

When Blanchandine meets the angel, she is presented with a choice. The angel says:

Jesus, who made the world, now asks you which you would prefer – speak honestly: to remain a woman, as he created you, or to become a man? The choice is yours. You will be a man, if you wish, because he will change you, and give you everything that belongs to a man. Now speak your desire, because it will be according to your wish.23

According to Butler’s analysis of the functioning of gender, this framing is paradoxical. We are shown the impossible instant in which the pre-gendered subject is free to decide on their own gender – impossible because it is only through gender that subjectivity can be achieved.24 However, as in Butler’s theorization, the notion of freedom to define the terms of one’s own subjectivity is revealed to be an illusion. Blanchandine decides to become a man because she believes that her husband, Tristan, is dead, and wishes to avenge him. Yet soon after the transformation has taken place, Blanchandine learns that Tristan is in fact alive. Far from avenging Tristan’s death, the newly transformed Blanchandin is now separated from his husband by his own altered embodiment, since, as he states: ‘“God certainly does not wish that a man should ever have another man in this mortal life”’.25 Thus it is clear that the transformation does not serve Blanchandin·e’s desires, but rather God’s plan: Blanchandin·e and their cousin Clarinde must conceive St Gilles.26 Attention to patterns of desire is crucial in trans readings, as interpretations of this affect can flatten transgender embodiment to a number of simplistic paradigms in which, for example, wanting is equated directly to being (one wants, therefore one is), or transgender desiring to be is construed as the imperfect analogue of cisgender being. Rhetorics of desire also permeate modern, ableist perceptions of disability. Disabled people, particularly those with chronic illness or chronic pain, are often subject to suspicion, assumed to lack sufficient desire – or sufficient willpower – to transcend their impairments.27 Here, the circumstances of Blanchandin·e’s transformation demonstrate that transgender embodiment is not something that the individual can control; it is not a question of desiring, but a question of being.

The angel describes God’s genealogical plan to Blanchandin·e as follows:

Lie with [Clarinde] as often as you please, for the first night that your body lies with hers, you will be able to engender […] an heir whom it will please God to crown richly for the good works that he will do. He will be called St Gilles.28

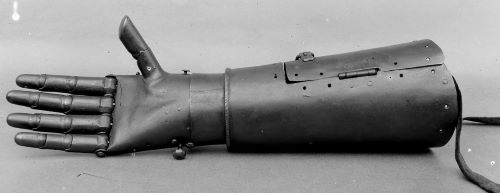

Metonymic use of ‘your body’ (‘ton corps’) for ‘you’, ‘my body’ (‘mon corps’) for ‘me’, etc, occurs throughout Tristan de Nanteuil. This insistence on embodiment as being, embodiment as identity, supports and informs my analysis of the primacy of the body in this text. Following his transformation, Blanchandin and Clarinde conceive St Gilles, as the angel had prophesied. Soon after Gilles’ birth, however, the new family is separated when their home is attacked in revenge by ‘pagan’ Greeks whom Blanchandin had forcibly converted. Blanchandin’s left arm is cut off, and he spends the next thirty years searching for his son, the only one who will be able to reattach the amputated limb. In this way, Blanchandin’s body itself becomes a shibboleth that facilitates both a family reunion and the recognition of Gilles’ sanctity. Blanchandin·e’s body is not Gilles’ body, yet transformation, impairment, and cure are successively imposed upon it to serve Gilles’ needs; without Blanchandin·e, Gilles could not be the saint that he is in this text. After the amputation of his arm, Blanchandin spends fifteen years begging, followed by fifteen years restored to the rank of knight, using an iron prosthetic arm to hold his shield. Thus, during his thirty-year search for his son, Blanchandin embodies two of the categories of individuals of whom Gilles is the patron saint: beggars, and people with physical impairments.29 By the end of the narrative, Blanchandin’s disabled trans body has been restored to wholeness by Gilles’ holy body. This wholeness is shared between the two physical forms. According to the logic of the text, both are rendered more ‘perfect’ (Blanchandin is cured, and Gilles is demonstrated to be a saint) by this interaction. We do not hear Blanchandin speak in the aftermath of the miracle. The cripistemologies to which Blanchandin had access in his disabled embodiment disappear silently with the reattachment of his arm. Following the miracle, the attention of the text is refocused on Gilles; it is he who is demonstrated to possess unique and valuable embodied knowledge. But are cripistemologies lost, or rather transformed? Gilles takes Blanchandin’s narrative place as the connective node around whom the rest of the characters coalesce, and one type of specific, situated knowledge is transfigured into another through the transformative moment of cure.

Notions of Cure

Kafer’s political/relational model of disability ‘[sees] “disability” as a potential site for collective reimagining’, producing activist community solidarity.30 The political/relational model is radically inclusive, making space for anyone who is not fully able-bodyminded, whether temporarily or permanently. This intrinsic openness empties the notion that able-bodymindedness can be a concrete or enduring form of embodiment. Simultaneously, work by Kafer, McRuer and others indicates the pervasive cultural bracketing of queerness and disability as ‘abnormal’ or ‘unnatural’ embodiments. Disabled and transgender embodiments, as disruptions to the fantasized states of automatic cisheterosexuality and automatic able-bodymindedness, are structurally constituted. Thus each exists as part of a fluid, relational nexus; as McRuer’s analysis demonstrates, neither able-bodiedness nor cisheterosexuality is ever more than a fantasy of completeness. Kafer argues that ‘disability is experienced in and through relationships; it does not occur in isolation’; and I propose that the same is true of transgender embodiment.31 Each comes into signification and comprehension only through relation to the abilities, sensations, and physical experiences of other bodyminds – and each is stigmatized through comparison to bodyminds recognized as more socio-culturally normate.

Alyson Patsavas describes pain as: ‘[A] fluid, relational, and […] leaky experience that f lows through, across, and between always-already connected bodies’.32 We might think of transgender embodiment in a similar manner. Gender itself is social and situational, and produced through relationships. Sanctity, as we have seen, operates relationally, orienting communities around the saintly body. Cure, too, is relational; its technologies and performances are typically prescribed to a patient by an authority. Many disabled people oppose rhetorics of cure, rejecting the medical model that situates disability within the individual. The medical model seeks to remove disability even at the cost of removing disabled human beings from society via institutionalization, euthanasia, eugenics, and selective abortion. Alternative models, such as the social model and Kafer’s political/relational model, locate disability within the (built) environment, and the social structures and discourses that limit the participation of impaired bodyminds. As Eli Clare writes: ‘At the center of cure lies eradication and the many kinds of violence that accompany it’.33 The eradication of disability constitutes the eradication not only of bodyminds, but of cripistemologies: human ways of being, and of knowing, which have intrinsic value.34 Similarly, trans people typically do not see themselves as requiring a ‘cure’ because the trans bodymind is not a defective version of a cis bodymind, but a facet of human diversity. Trans embodiments generate trans epistemologies, distinct forms of embodied knowledge and knowledge production which, like cripistemologies, are often unknown to or devalued by normative discourse. Their disappearance, if disabled and/or trans lives were somehow to cease to exist, would constitute a significant loss to the sum of human expertise. Cripistemologies and trans epistemologies not only carve out space for marginalized existences in the present, but render disabled and trans futures thinkable, and therefore possible.35 When medieval cure operates in a sacred perspective, it does not enact eradication, but rather relationality, proximity, and futurity. Pain or impairment is transferred or transformed, and functions to forge bonds both human and divine.

The reader of Tristan de Nanteuil is taught to envision impairment in a relational mode. In the passage preceding Blanchandine’s transformation into Blanchandin, this secular text takes a turn for the hagiographic, declaring itself worthy of being preached as a sermon before offering its own theorization of the meaning of disability:

If a good person experiences any obstacle (encombrier), they should realize that God has sent it to them; and the one who is most afflicted owes the most thanks to God. This is how God demonstrates his love and welcomes one to the glory of heaven; this [affliction] is the payment.36

Physical impairment is thus located within the extremely broad category of ‘obstacle’ (‘encombrier’); anything that interrupts expected or anticipated patterns of experience is essentially rendered equivalent in both effect and signification. Notably, for Blanchandin·e this category includes both becoming trans and becoming impaired. Yet at the same time that this theorization relies upon the undesirability of the ‘obstacle’ – for how else is it to be identified as such? – the model seamlessly reframes what is supposedly inherently undesirable as precisely that which should be desired. Disability is revealed to be not only relational (it is sent by God), but also transactional: it constitutes the necessary payment for a paradisiac future in which the notion of disability – along with the notion of ability – ceases to exist. This structure enables the apparently radical proposal of desiring disability, yet the desire is always predicated on the certain eradication of the supposedly desired state. That is: one may aspire to impairment, since such experience connotes contact with the divine. However, impairments are always and only ever temporal, and therefore temporary. Whether in this life or the next, a cure will be enacted, and the bodymind will be ‘returned’ to the fantasized state of wholeness. This promise of perfection reveals that, when disability is desired in this context, what is truly desired is the radically non-disabled state which can be accessed by means of earthly impairment.

Narrative Prostheses

The paradigm described above resonates with David T. Mitchell and Sharon L. Snyder’s analysis of the function of disability within narrative, which demonstrates that a fundamental operation of narrative is to rehabilitate or f ix deviance. Mitchell and Snyder’s theory of narrative prosthesis reveals how disability frequently serves as a plot mechanism, driving and shaping the narrative until its own elimination can be achieved.37 Blanchandin’s amputated arm functions in this manner. It serves as a device to ensure the eventual reunion of parent and child, as well as to dramatically and conclusively demonstrate Gilles’ saintly status through the miraculous healing. Both the text’s own structure, and Mitchell and Snyder’s theorization, are predicated on the ultimate effacing of impairment, which is what appears to happen when Blanchandin’s arm is reattached. But when disability is understood through a relational model, can it ever really disappear? Or is it simply reoriented or relocated, as an integral aspect of a network of vulnerable bodies? As Spencer-Hall notes in relation to another medieval tale of miraculous healing: ‘Disability can never be annihilated; instead, it is forever reconstituted along relational pathways’.38

In the course of the text, Blanchandin·e welcomes physical events ranging from thorn pricks, to transformation from female to male, to the loss of a limb, since each is an expression of God’s will. When she encounters the angel who transforms her into a man, Blanchandine is fleeing through the forest. She prays as she runs, believing that her husband, Tristan, is dead. The text casts this journey as a process of abjection in the model of saintly mortification; we are told that she willingly takes the path where she sees most thorns. The narrative continues:

She weeps and sighs very piteously; her legs and feet are bloody, and as soon as a thorn causes her heart to suffer, she throws herself to her bare knees with admirable desire and says: ‘God, I worship you and fervently thank you for whatever you send me; my body gratefully accepts it. I want to endure this torment in your name, and in honour of Tristan and his salvation. The penance that I will have to perform for a long time, I perform in his name, so that on the Day of Judgement he may dwell with you on high’.39

Here, pain and physical change are demonstrated to exist not only in relation to God, but also in relation to another person – someone that Blanchandine believes is dead, and on whose behalf she wishes to intercede. The relational web that produces disabled embodiment is thus shown to encompass at least three categories of beings: God, living people, and dead people. While in much of modern culture – particularly medical(ized) discourses – pain is framed as ‘an isolating, devastating experience’, for Blanchandine, pain is a sign that she is not alone.40 The sensation affirms that she is accompanied by God, and is held in relation both to him and to other mortal beings, including Tristan. God is the source of embodied experience, which must be rendered meaningful through its active interpretation as part of a transactional relationship with him. Blanchandine’s pain also connects her to her husband: she can bargain with God to transform the meaning of her suffering, such that its result, the obliteration of suffering, is transferred to Tristan. Thus, all three are linked by the relational network. The metonymic use of ‘my body’ (‘moncorps’) instead of ‘I’ once again demonstrates that the text operates on a logic of embodiment, rather than a logic of identity.

The next section of the text sees Blanchandine transformed into Blanchandin; the text states that: ‘[W]hen he saw himself transformed, he praised Jesus Christ’.41 It is notable that the changes to Blanchandine’s body are presented as straightforwardly additive, and focused on the genitals. Much is made of Blanchandin’s new penis, the literalized narrative prosthesis that permits the continuation of God’s plan, Blanchandin’s lineage, and the text itself. When he meets Tristan’s half-brother, Doon, Blanchandin has to display ‘his flesh, which was completely changed below the belt’ in order to convince Doon that he is now a man.42 Blanchandin’s penis is soon displayed to all and sundry at court as he takes a bath. The ability that a penis implicitly demonstrates, of course, is the ability to engender a child; the narrative again underscores that it is for the sake of the yet-to-be-born St Gilles that Blanchandin·e’s body has been transformed. This casts the pre-transformation, female Blanchandine both as lacking in ability, and as physically lacking, or incomplete; both these ‘lacks’ are ‘cured’ by the angel. This transformative ‘cure’ reflects the misogynistic moral hierarchy expounded by early church fathers such as St Jerome, who wrote that a devout woman ‘will cease to be a woman and will be called man’ (‘mulier esse cessabit, et dicetur vir’).43 Blanchandin’s altered body both reflects and enacts his altered relationship to God, as well to the saintly future son he is required to engender. This divinely ordained reproductive futurism calls normative modern understandings of queer and crip futures into question.44 According to certain pervasive modern discourses, queer people cannot reproduce (since reproductive sex is equated to cisheteronormativity), whereas disabled people should not reproduce (because they ‘risk’ reproducing disability). Blanchandin’s reproductive future, however, is not only possible, but essential.45 The transformation of his body enables the conception of St Gilles, while the loss of his arm produces the cripistemolo-gies that shape Gilles’ embodiment as he ‘comes out’ as a saint. Thus, the network of embodied relations is shown to link not only God, the living, and the dead, but also angels, saints, and the unborn.

Fragmentation and Reassembly

When Blanchandin’s arm is severed, he responds by praising and thanking God; he interprets the impairment as a direct ref lection of his moral status:

Lord God who, from death, returned to life, I know well that through some foolish action I have deserved the great torment that I am in, and the great suffering, and I accept it willingly.46

Blanchandin relates the injury to God not only as its source, but also as a model for how to live this experience. God himself has experienced greater physical disability; thus, mortal impairments are at once trivial (because they cannot compare to Christ’s suffering) and significant (because they replicate this suffering, however faintly). Here I use the term ‘suffering’ to reflect Blanchandin’s statements about his experience, yet in medieval Western Christianity, pain and impairment were frequently conceptualized as both positive and productive.47 Similarly, modern crip theory challenges the ableist assumption that pain and impairment can only be experienced as suffering.48 Yet in the central paradox of Christian redemption, as presented in Tristan de Nanteuil, disability is to be desired and welcomed in the knowledge that impairment exists only to be erased. If God is the paradigm of total ability, which humans, though made in his image, can never approximate, then Jesus is the model of ‘perfect’ disability, which is only ever transitory, and always ennobling. Christ therefore fits Sami Schalk’s archetype of the ‘superpowered supercrip’: ‘a character who has abilities or “powers” that operate in direct relationship with or contrast to their disability’.49 The imitatio Christi practiced by disabled saints, in turn, reveals them as ‘glorified supercrips’, disabled characters who achieve dramatic feats through hard work. Yet Schalk notes that such characters benefit not only from their own ‘extraordinary and compensating qualities’, but also from significant socio-cultural privilege.50 The privilege of saints is their relationship with God which, in a circular and paradoxical paradigm, provides and affirms the sanctity that their actions perform and declare.

The promise of paradise is that this complex relational network will collapse into oneness with God; notions of ability and disability, along with the concept of bodymindedness itself, will no longer be relevant. The apparent wholeness and completion of resurrection, however, will be composed – figuratively, but also perhaps literally – of the wounds and fractures that earned and marked fitness for heaven.51 Cure cannot, therefore, eradicate impairment, because lived experiences of disability constitute complex and valuable ways of being human. These experiences produce the cripistemologies that multiply links between community members, but also link the entire community to the divine. Similarly, transgender embodiment, as a way of sensing, experiencing, and relating to the body otherwise, produces trans epistemologies with communal effects.52

Following Blanchandin’s injury, his status as quasi-saint is solidified as he becomes a kind of living relic; he is informed by an angel that he must carry his severed arm with him as he searches for his son, since Gilles alone can cure him. When Blanchandin is finally reunited with his son, the saint receives the arm as if it is a cross between a long-lost relative and a holy relic, which is in fact the case. He marvels to find it incorrupt after thirty years: ‘When Gilles holds the arm, straight away he begins to kiss it; he hugs it in his arms and squeezes it tightly. He is astonished that it is so rosy.’53 This transfer of the arm from Blanchandin to Gilles once again literalizes narrative prosthesis. This prosthesis is transformed throughout the text from Blanchandine’s phantasmatic phallus, to Blanchandin’s ‘large and thick’ penis (‘gros et quarrés’), to Blanchandin’s severed arm, to Gilles’ sanctity.54 Each in turn serves as the focal point that structures the relational web linking the text’s characters. The moment when Gilles receives the arm figures the fusion of Blanchandin’s trans cripistemology with Gilles’ sacred epistemology. This is not an erasure, but a cumulative process of knowledge development, shared between intimately connected yet differently situated bodies. The passing of the arm also reconfigures the relationship between father and son, impaired subject and healer. The shibboleth of the arm affirms that Gilles is Blanchandin’s son at the same time that it asserts Gilles’ place in another genealogy, the lineage of saints ordained by God. Their relationships revolve and transform around the locus of the theoretical narrative prosthesis, as well as the text’s literal prostheses.

St Gilles prays, and is empowered to reattach his father’s arm to his shoulder: ‘In front of twenty thousand Armenians, and in front of King Tristan, [Gilles] reattaches the severed arm to the stump, one flesh against the other, just as it was before’.55 The relational network in this moment of cure encompasses not only God, Gilles, and Blanchandin, but also the twenty thousand observers who are sutured into the system as witnesses to the miracle. Their presence transforms the healing into a highly charged symbolic event, designed not only to restore Blanchandin’s ability but to employ this spectacle as a means of bringing the observers closer to God. Similarly, the miracle of Blanchandin·e’s transformation serves as a catalyst for Gilles’ own piety. When, as a boy, he hears his mother speak of his father’s transformation, the narrative affects him profoundly:

[W]hen the child hears this, he thanks God and His sweet mother with all his heart. His father’s miracle enlightens him so greatly that he places his desire and his heart and all his certainty in Jesus, the all-powerful father.56

Once again, transgender embodiment is revealed not as a dereliction of divine order, as many branches of twenty-first century Christianity declare, but rather as a radiant expression of God’s will. Although both Blanchandin and Christ are undoubtedly male, each was formed from female flesh: Blanchandin from Blanchandine, and Christ from Mary.57

Throughout the text, physical changes are enacted upon the quasi-saint Blanchandin·e for the sake of St Gilles. The narrative trajectory of the pair demonstrates the paradoxically conjoined-yet-separated embodiments of parent and child, impaired person and sacred healer. It is Gilles who is marked as holy, who is demonstrated to possess a hyper-able saintly body whose non-normative abilities include the power to reattach amputated limbs. Yet Blanchandin·e’s body, too, manifests hyper-ability: his incorrupt severed arm proves that he has non-normative physical aptitudes. So, too, does the transformation from female to male. God’s will is always required in order for these abilities to be exhibited, but then God’s will is similarly implicated in impairments and cures.58 The necessity for divine involvement does not negate the part played by human bodies in these depictions of non-normative ability; rather, it affirms the relational aspect of these shifting embodiments. Blanchandin·e’s malleable body made Gilles’ existence possible. In addition to being a quasi-saint, Blanchandin·e, too, can be figured as supercrip. It is doubly through Blanchandin·e that Gilles’ sacred identity emerges; the pair are locked in a mutually dependent, mutually defining kinship. Sacred, impaired, and transgender embodiments, as they are presented in Tristan de Nanteuil, can be conceptualized in similar ways. The nexus of embodiment, impairment, and cure flows through, across, and between St Gilles and Blanchandin·e; their physical forms are altered through their embodied relations to each other, and to the divine.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Cazelles, Le Corps, p. 48: ‘La mort du saint est […] l’étape initiale du phénomène hagi-ographique […]. L’intérêt pour le mort a ainsi suscité le désir d’en savoir plus sur sa vie.’ All English translations in the main body of the text are my own.

- On saints and time, see: Spencer-Hall, Medieval Saints, pp. 65-105.

- Bynum, Fragmentation, p. 13.

- See Spencer-Hall, ‘Wounds’, pp. 399-400; p. 405.

- Kafer, Feminist, Queer, Crip, p. 7.

- The term ‘bodymind’ reflects ‘the imbrication (not just the combination) of the entities usually called “body” and “mind”’: Price, ‘Bodymind Problem’, p. 270.

- See Spencer-Hall, ‘Wounds’, p. 396; pp. 408-09.

- On the term ‘able-bodyminded(ness)’, see Sheppard, ‘Using Pain’, pp. 55-56.

- Spencer-Hall, ‘Wounds’, p. 396.

- Ibid., p. 390.

- Campbell, Contours of Ableism, p. 12.

- See Spencer-Hall, ‘Chronic Pain’.

- McRuer, Crip Theory; Butler, ‘Imitation’, p. 21.

- McRuer, Crip Theory, p. 9.

- See Bynum, Jesus as Mother, pp. 110-169; Gutt, ‘Transgender Genealogy’ and ‘Medieval Trans Lives’; and in this volume, ‘Introduction’ (pp. 24-27), Newman (pp. 43-63, especially 47, 54, 59), Wright (pp. 155-76), Ogden (pp. 201-21), Bychowski (pp. 245-65).

- There are also saints who inflict ‘miracles’ of injury or impairment; see relevant chapters in Spencer-Hall, Grace-Petinos, and Pope-Parker.

- See, for example, Spencer-Hall, ‘Chronic Pain’; Spencer-Hall, Grace-Petinos and Pope-Parker. On cripistemologies, see Patsavas, ‘Recovering’; Johnson and McRuer, ‘Introduction’.

- Chanson d’aventures is the name given to some later examples of the chanson de geste genre, in which the focus shifts from battles to marvellous adventures.

- Paris, France, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS Français 1478. The critical edition is Sinclair, Tristan de Nanteuil.

- Gilles, also known as St Giles or St Aegidius, appears in the Golden Legend, and is the subject of a twelfth-century Anglo-Norman Life, La Vie de saint Gilles, based on the Latin Vita sancti Aegidii, dated to the tenth century (Guillaume de Berneville, Vie, pp. xvii-xviii). Tristan de Nanteuil rewrites the saint’s story, retaining only a few key motifs.

- See Gutt, ‘Transgender Genealogy’, pp. 140-41.

- See ‘Identified Gender’ in the Appendix: p. 301.

- ‘“Or te mande Jhesus qui le monde estora, | Lequel tu aymes mieulx, or ne me celles ja : | Ou adés estre femme ainsy qu’i te crea, | Ou devenir ungs homs? A ton vouloir sera. | Homs sera, se tu veulx, car il te changera | Et te donrra tout ce qu’a home appertendra. | Or en di ton vouloir, car ainsy il sera | Selon ta voulenté.”’ Sinclair, Tristan de Nanteuil, ll. 16142-49.

- Butler, Bodies that Matter, pp. xvi-xvii. For further analysis of this moment in Tristan de Nanteuil, see Gutt, ‘Transgender Genealogy’, p. 141.

- ‘“Dieu ne le veult mye | C’oncques homs ne f ist aultre en celle mortel vie”’. Sinclair, Tristan de Nanteuil, ll. 16283-84.

- On Blanchandin·e and Clarinde’s relationship, and the steps taken to ensure the legitimacy of their union, see Gutt, ‘Transgender Genealogy’, pp. 137-38.

- On chronic illness, see Wendell, ‘Unhealthy Disabled’, p. 29; on chronic pain, see Patsavas, ‘Recovering’, pp. 210-11.

- ‘“couches o lui tant quë il te plaira, | Car la premiere nuyt que ton corps y gerra, | […] pourras engendrer ung hoir que Dieu vourra | Haultement couronner pour le bien qu’i fera ; | Saint Gilles yert clamés”’. Sinclair, Tristan de Nanteuil, ll. 16187-91.

- On disability and begging in the Middle Ages, see Metzler, Social History, pp. 154-98.

- Kafer, Feminist, Queer, Crip, p. 9.

- Ibid., p. 8.

- Patsavas, ‘Recovering’, p. 213.

- Clare, Brilliant Imperfection, p. 26.

- Wendell, ‘Unhealthy Disabled’, pp. 31-32.

- On trans epistemologies see Ridley, ‘Imagining Otherly’; Radi, ‘Políticas’; McKinnon, ‘Allies’, pp. 170-71.

- ‘[S]e bonne persone a aucun encombrier, | Il doit penser que Dieu lui a fait envoier ; | Et qui plus a d’anoy, plus le doit gracïer ; | Ensement l’ayme Dieu et le fait heberger | En la gloire des cieulx et la le fait paier.’ Sinclair, Tristan de Nanteuil, ll. 15781-85.

- Mitchell and Snyder, Narrative Prosthesis, pp. 6-8.

- Spencer-Hall, ‘Chronic Pain’, p. 62.

- ‘Elle pleure et souspire assés piteusement ; | Les jambes et les piés lui estoient senglant, | Et sy tost c’une espine lui fait au ceur tourment, | A nuz genoulx se gette d’amourable tallant | Et dit : “Dieu, je t’aoure et te graci granment | De quanques que m’envoyes ; mon corps en gré le prent. | Je veul ou non de toy endurer le tourment | En l’onneur de Tristan et de son sauvement. | La penance qu’aray a fere longuement, | Je le fais en son non, par quoy au Jugement | Puist avoir avec toy lassus hebergement.”’ Sinclair, Tristan de Nanteuil, ll. 16085-95.

- Patsavas, ‘Recovering’, p. 204. Scarry’s foundational discussion of pain contends that ‘pain comes unsharably into our midst as at once that which cannot be denied and that which cannot be conf irmed’ (p. 4). Although this view is still widespread, Scarry’s analysis has been extensively challenged and productively nuanced by work including: van Ommen, Cromby, and Yen, ‘New Perspectives’; and Gonzalez-Polledo and Tarr, Painscapes (see especially pp. 5-10). Patsavas emphasizes that ‘we never experience pain in isolation’ (‘Recovering’, p. 209). Work such as Patsavas’s is inherently political, revealing and subverting ableist medical discourses that view pain as insupportable, and thus the lives of those with chronic pain as less valuable (even eradicable, if this is the only way that the pain can be ‘cured’).

- ‘Quant se vit transmué, Jhesus Crist en loa’. Sinclair, Tristan de Nanteuil, l. 16204.

- ‘[S]a char qui toute estoit changie | Par dessoubz le braiel’. Ibid., ll. 16240-41.

- See Mills, Seeing Sodomy, pp. 205-06.

- On the logics of reproductive futurism, see Edelman, No Future; and McLoughlin in this volume (pp. 65-85).

- See Gutt, ‘Transgender Genealogy’.

- ‘“Beaus sire Dieu qui de mort vins a vie, | Bien sçay, j’ay desserv y par aucune folie | Le gref tourment que j’ay et la grant maladie ; | Et je le prens en gré.”’ Sinclair, Tristan de Nanteuil, ll. 17965-68.

- Spencer-Hall, ‘Chronic Pain’, pp. 52-53.

- Patsavas, ‘Recovering’, pp. 203-04.

- Schalk, ‘Supercrip’, p. 81.

- Ibid., p. 80.

- On medieval Western Christian conceptions of bodily resurrection, see Bynum, Fragmentation, pp. 227-31. On this and modern technologies, see: Spencer-Hall, Medieval Saints, pp. 77-102.

- See Ridley, ‘Imagining Otherly’, pp. 485-86.

- ‘Quant Gilles tint le bras, adonc le va baisant, | Entre ses bras l’acolle et l’alla estraignant, | De ce qu’est sy vermeil se va esbahissant.’ Sinclair, Tristan de Nanteuil, ll. 22790-92.

- Ibid., l. 16357.

- ‘Devant .xx. mille Ermins et devant roy Tristan | Va la brace tranchee au mongnon resoudant, | L’une char contre l’aultre aussy fut que devant’. Ibid., ll. 22814-16.

- ‘[Q]uant ly enf fes va celle chose escoutant, | Dieu et sa doulce mere va de ceur gracïant. | Le miracle son pere le va enluminant | Tellement qu’a Jhesus, le pere tout poissant, | Mist entente et courage et tout son essïent.’ Ibid., ll. 19766-70.

- See Bynum, Fragmentation, p. 172, and Sexon in this volume (pp. 133-53, especially 135-41).

- See also Elphick in this volume (pp. 87-107, especially 87, 91, 94-95).

Bibliography

- Butler, Judith, Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex” (London: Routledge, 2011 [1993]).

- —, ‘Imitation and Gender Insubordination’, in Inside/Out: Lesbian Theories, Gay Theories, ed. by Diana Fuss (London: Routledge, 1991), pp. 13-31.

- Bynum, Caroline Walker, Fragmentation and Redemption: Essays on Gender and the Human Body in Medieval Religion (New York: Zone, 1991).

- —, Jesus as Mother: Studies in the Spirituality of the High Middle Ages (Berkeley: University of California, 1982).

- Campbell, Fiona Kumari, Contours of Ableism: The Production of Disability and Abledness (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009).

- Cazelles, Brigitte, Le Corps de sainteté, d’après Jehan Bouche d’Or, Jehan Paulus et quelques vies des XIIe et XIIIe siècles (Geneva: Droz, 1982).

- Clare, Eli, Brilliant Imperfection: Grappling with Cure (Durham: Duke University, 2017).

- Edelman, Lee, No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive (Durham: Duke University, 2004).

- Gonzalez-Polledo, EJ, and Jen Tarr, eds., Painscapes: Communicating Pain (London: Palgrave McMillan, 2018).

- Gutt, Blake, ‘Medieval Trans Lives in Anamorphosis: Looking Back and Seeing Differently (Pregnant Men and Backwards Birth)’, Medieval Feminist Forum, 55.1 (2019), 174-206.

- —, ‘Transgender Genealogy in Tristan de Nanteuil’, Exemplaria, 30.2 (2018), 129-46.

- Johnson, Merri Lisa, and Robert McRuer, ‘Cripistemologies: Introduction’, Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies, 8.2 (2014), 127-47.

- Kafer, Alison, Feminist, Queer, Crip (Bloomington: Indiana University, 2013).

- McKinnon, Rachel, ‘Allies Behaving Badly: Gaslighting as Epistemic Injustice’, in The Routledge Handbook of Epistemic Injustice, ed. by Ian James Kidd, José Medina, and Gaile Pohlhaus, Jr. (New York: Routledge, 2017), pp. 167-74.

- McRuer, Robert, Crip Theory: Cultural Signs of Queerness and Disability (New York: New York University, 2006).

- Metzler, Irina, A Social History of Disability in the Middle Ages: Cultural Considerations of Physical Impairment (New York: Routledge, 2013).

- Mills, Robert, Seeing Sodomy in the Middle Ages (Chicago: University of Chicago, 2015).

- Mitchell, David T., and Sharon L. Snyder, Narrative Prosthesis: Disability and the Dependencies of Discourse (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 2001).

- van Ommen, Clifford, John Cromby, and Jeffery Yen, eds., ‘Elaine Scarry’s The Body in Pain: New Perspectives’, Subjectivity, 9.4 (Special Issue:) (2016).

- Patsavas, Alyson, ‘Recovering a Cripistemology of Pain: Leaky Bodies, Connective Tissue, and Feeling Discourse’, Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies, 8.2 (2014), 203-18.

- Price, Margaret, ‘The Bodymind Problem and the Possibilities of Pain’, Hypatia, 30.1 (2015), 268-84.

- Radi, Blas, ‘Políticas del conocimiento: hacía una epistemología trans*’, in Los mil pequeños sexos: Inter venciones críticas sobre políticas de género y sexualidades, ed. by Mariano López Seoane (Sáenz Peña, Argentina: Eduntref, 2018), pp. 27-42.

- Ridley, LaVelle, ‘Imagining Otherly: Performing Possible Black Trans Futures in Tangerine’, TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly, 6.4 (2019), 481-90.

- Scarry, Elaine, The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World (New York : Oxford University, 1985).

- Schalk, Sami, ‘Reevaluating the Supercrip’, Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies, 10.1 (2016), 71-86.

- Sheppard, Emma, ‘Using Pain, Living with Pain’, Feminist Review, 120 (2018), 54-69.

- Spencer-Hall, Alicia, ‘Christ’s Suppurating Wounds: Leprosy in the Vita of Alice of Schaerbeek (†1250)’, in “His brest tobrosten”: Wounds and Wound Repair in Medieval Culture, ed. by Kelly DeVries and Larissa Tracy (Leiden: Brill, 2015), pp. 389-416.

- —, ‘Chronic Pain and Illness: Reinstating Crip-Chronic Histories to Forge Affirmative Disability Futures’, in A Cultural History of Disability in the Middle Ages, ed. by Jonathan Hsy, Joshua Eyler, and Tory Pearman (London: Bloomsbury, 2020), pp. 51-66.

- —, Medieval Saints and Modern Screens: Divine Visions as Cinematic Experience (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University, 2018).

- Spencer-Hall, Alicia, Stephanie Grace-Petinos and Leah Pope-Parker, eds., Disability and Sanctity in the Middle Ages, 2 vols. (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University, forthcoming 2022/2023).

- Wendell, Susan, ‘Unhealthy Disabled: Treating Chronic Illnesses as Disabilities’, Hypatia, 16.4 (2001), 17-33.

Chapter 9 (223-244) from Trans and Genderqueer Subjects in Medieval Hagiography, edited by Alicia Spencer-Hall and Blake Gutt (Amsterdam University Press, 04.06.2021), published by OAPEN under the terms of an Open Access license.