The pose is fascinating for all it suggests about Brown’s hopes for the country and the actions he might take to fight slavery.

By Dr. William Frank Mitchell

Instructor, Urban and Community Studies

University of Connecticut, West Hartford

Introduction

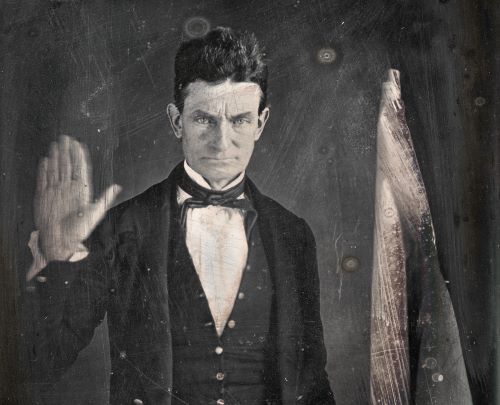

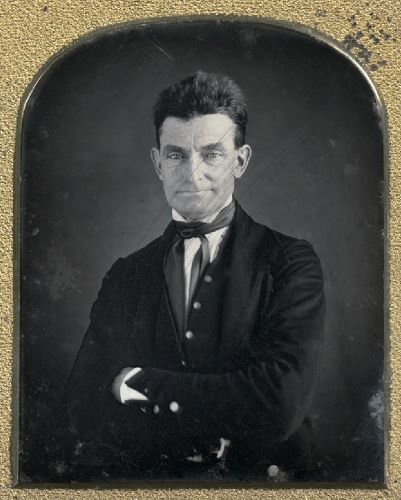

Staring directly at the viewer with his right hand raised, palm facing out, his left hand gripping a flag, the abolitionist John Brown was photographed in Hartford, Connecticut in 1846 by the professional daguerreotypist, Augustus Washington. Brown’s right hand is raised as if pledging allegiance, taking a silent oath, or warning the viewer to stop. The pose is balanced by the hand holding a flag believed to be the emblem for Brown’s Subterranean Pass-Way (an alternate Underground Railroad, intended to draw enslaved Black people North towards New York and the Adirondacks). The pose is fascinating for all it suggests about Brown’s hopes for the country and the actions he might take to fight slavery. What might Brown be suggesting about his expectations for the future in this early photograph?

Considering the relationship between the white abolitionist sitter, John Brown, and the free Black photographer, Augustus Washington, is equally fascinating. Who decided for Brown to stand in such a manner? To hold the flag? Who determined that Brown should be standing and not sitting, with eyes fixed ahead? How did this interaction between a white and a Black man produce one of the most potent photographic portraits of the 19th century?

Augustus Washington

Augustus Washington was born in Trenton, New Jersey in 1820 or 1821 to a formerly enslaved father and an Asian mother who died while he was quite young. Washington’s father and stepmother encouraged his education, and he attended a multi-racial school. His commitment to his studies meant that by his teen years, Washington was a teacher in a local school for Black children in New Jersey. He left for New York to study at the Oneida Institute. With his limited family resources, Washington was forced to leave Oneida when he had spent through his savings. He taught at a Black public school in Brooklyn in the early 1830s and hoped to attend Dartmouth College in New Hampshire with the money he saved. His activist friends suggested the Kimball Union Academy instead, and Washington joined the class of 1843. After graduation he attended Dartmouth. Concerned about expenses at the semester break, he invested in daguerreotype equipment and began photographing friends, neighbors, and residents.

New York’s Oneida Institute was the most progressive school of the early 19th century. Founded in 1827, the school’s patrons included abolitionist financiers the Tappan brothers and prominent anti-slavery religious leaders from around the Northeast. In its first five years the school’s leaders committed the institution to abolitionism. The potential funding pool for schools focused on abolitionist activism and racial equality was small and the Oneida Institute closed in 1843. Oneida alumni became leading figures in 19th century abolitionism.

The end of slavery was not a priority for New Hampshire’s Kimball Union Academy at its founding in 1813. Later on, the school’s fourth principal, Cyrus S. Richards, embraced abolitionism and the boarding school admitted several Black students during his tenure.

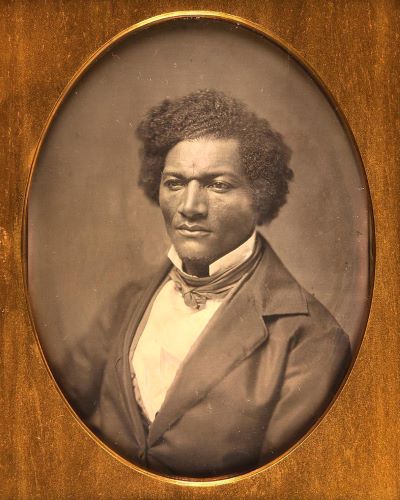

In 1839, French inventor Louis Daguerre developed the daguerreotype: a silver-coated copper plate, which after exposure to heat, light, salt baths, mercury, and gold chloride, reflects the subject’s image. Daguerreotypes were seen as a magical union of art and science that Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, and other Black Americans believed could impart some element of truthful representation that media, such as painting, drawing, and prints could not. Photographs could combat racist renderings of Black people by reinforcing representations of Black humanity rather than caricature. As he toured the country, Frederick Douglass scheduled photographic portrait sittings in many of the cities he visited. He shaped his portrait image as carefully as any 21st-century image maker might to emphasize dignity, humanity, and the serious nature of anti-slavery work. He didn’t smile and he knew which side and angle were his best. Douglass wrote frequently about photography and progress, and he became the most photographed American of his time.1

For Washington, the public interest in daguerreotypes generated enough money for him to focus on his classes at Dartmouth for the semester. However, in 1844 Washington left the isolation of Hanover, New Hampshire for Hartford, Connecticut’s comparatively bustling Black community where he taught at the school run by one of the nation’s first Black Congregational churches, the Talcott Street Church’s school. It was in Hartford that he also eventually resumed his daguerreotype practice.

In 1819, Black parishioners from Hartford’s First Congregational Church began organizing their own worship. They decided that the first African American Congregational church needed a Sunday School, and by 1820 a Sunday School had been approved. Black residents’ frustration with Hartford’s public school options pushed church leaders to seek funds for a district school at the African Religious Society then called the Talcott Street Church. By 1830 the school had its first students.

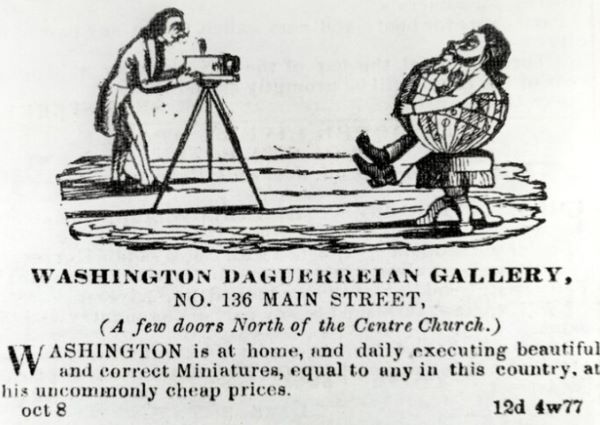

Washington led the church’s African School until 1846, and in that first year he paid his debt to Dartmouth and collected the photography equipment and books he’d left in Hanover. He ran an ad in a December 1846 issue of the local Hartford antislavery newspaper The Charter Oak. It publicized the “durable memento” of a daguerreotype as a cheap and beautiful Christmas present.

Washington advertised in other regional antislavery papers and made his abolitionist colleagues a primary audience. Between New York and Boston, the New Haven, Hartford, Springfield corridor linked a network of activist churches, abolitionist funders, and committed free Black communities that had been galvanized by the 1830s legal cases against Prudence Crandall’s school for Black girls, against the Amistad captives fight for freedom, against a proposed college for African Americans in New Haven, and other outrages.

Prudence Crandall, a white woman from Rhode Island, accepted Sarah Harris, an African American girl, at her Canterbury, Connecticut girls boarding school in 1832. Harris was the school’s first African American student and parents of other students did not welcome her. Before long Crandall was the head of a school exclusively for African American girls, which wasn’t popular with the town. Harassment from Canterbury residents, laws restricting educational access for Black students, and legal trials followed. Crandall closed the school in 1834 and left the state with her husband. Harris and several of the other Black students realized their educational goals to become activists, abolitionists, and educators at schools for African Americans.

In June of 1839 a group of 53 Mendi captives stolen from Sierra Leone boarded the Amistad schooner for a voyage to a Cuban plantation. Several days into the journey the captives seized control of the ship and insisted the surviving crew sail them home. A Navy ship stopped the Amistad on Long Island Sound and the captives were taken to jail in Connecticut. Abolitionists rallied and the captives went to trial in Hartford. An 1840 decision recognized the captives had been free people illegally taken from West Africa. An appeal went to the Supreme Court and in 1841 the justices affirmed the earlier decision: the Amistad captives were free.

New Haven abolitionist Simeon Jocelyn and New York, African American, Episcopal priest Peter Williams proposed a college for Black students to participants at the 1831 civil rights Convention in Philadelphia. William Lloyd Garrison, Arthur Tappan, the Rev. James Pennington and other abolitionists supported the idea and agreed that New Haven made sense for economic, political, and educational reasons. Many New Haven leaders were unconvinced by the activists enthusiasm and advocacy. A raucous community campaign followed and led to the proposal’s defeat at a town meeting organized by New Haven’s mayor. New Haven would not be home to the first Historically Black College and University (HBCU).

Hartford in the mid-19th century was home to several nationally known activists such as the Reverend James Pennington and regionally recognized figures like the activist James Mars who survived slavery in northwest Connecticut and later published his memoir, A Life of James Mars, a Slave Born and Sold in Connecticut, Written by Himself in 1864. In Springfield, Mars’ brother, Methodist minister John Newton Mars, served a larger abolitionist community that assisted Black people escaping enslavement and tutored impassioned white abolitionists, including temporary resident John Brown, on life in a multi-racial neighborhood.

Photographing John Brown

As an abolitionist, and with his experience living in multi-racial Springfield, John Brown was probably more relaxed during his studio visit with Washington than other clients. Washington typically worked with white and wealthy Hartford residents whose business kept Washington financially stable into the 1850s, but were not necessarily seeking to fight for racial equality.

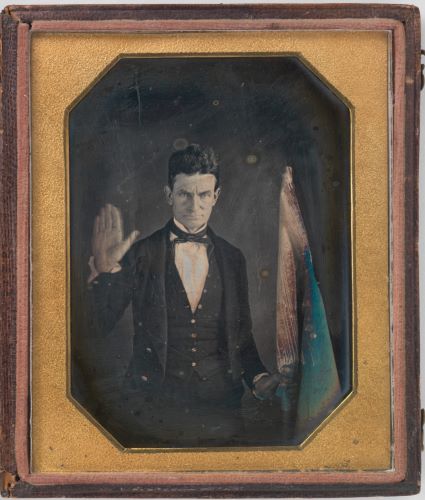

In Brown’s signature portrait from the sitting, the one introduced at the start of the essay, Washington captures Brown’s characteristically intense gaze and slightly stern expression. Yet another image from the sitting—which is in the collection of the Nelson Atkins Museum—feels like the after-hours portrait. It is an image of John Brown after the hard work of abolitionism is finished for the day. He is no longer posed to defend an oath or a flag, but instead with his arms comfortably crossed and slightly leaning back, he warily welcomes the viewer into this happier world. Brown’s face is relaxed into a pleasant expression if not an actual smile, and the sensible luxury of his cravat and shirt suggest this could have been a happy and prosperous period in his life. This image confirms that Brown was one of the most comfortable subjects to have spent time in Washington’s Hartford studio.

John Brown was a unique subject for Augustus Washington. The sensitivities Washington encountered as a 19th-century Black man photographing white men and women in a private studio are not surprising. Most of Washington’s Hartford subjects would have had few occasions when they were instructed or directed by an unfamiliar African American.

One such sitter was the well-known Hartford poet, Lydia Sigourney, who Washington photographed in 1852. Sigourney’s writings on slavery, abolition, and the colonization of Africa for African Americans suggest that she endorsed deportation to Africa as the solution for the freedom and equality for Black people in America, rather than equal citizenship in the United States. Thus, she couldn’t have seen Augustus Washington as her equal while sitting for her portrait.

Leaving for Liberia

Initially, Augustus Washington believed in America and expected the situation for free and enslaved Black people would improve. However, Washington, along with other free Black creatives, makers, and thinkers of the early 19th century lived in a country where they could not access the realities of freedom, the ideals of citizenship, and the rewards of creativity regularly invoked all around them. A generation of Black Northeasterners who lived through the American Revolution in the 1700s had begun discussions about moving abroad. In the early years of the Federal era, African American activists in Boston, Newport, and Philadelphia debated the benefits of leaving America permanently. Massachusetts-based Black and Indigenous shipping magnate Paul Cuffe promoted emigration as the route to new trade possibilities and employment opportunities for free Black workers. In 1815 Cuffe sailed 38 free Blacks from America to Sierra Leone through his Black-led repatriation effort.

The episode inspired other Black entrepreneurs and activists frustrated by the obstacles blocking their commercial and political ventures. Bowdoin College’s first Black graduate, John Brown Russwurm, class of 1826, taught school in Boston and started the first African American newspaper Freedom’s Journal, before leaving for Liberia within a decade of his graduation. Future efforts of Black-led repatriation would include the abolitionist physician Martin Delany’s journey to Liberia to negotiate terms for a Black American homeland in the 1850s. In the coming decades, Black hair-care tycoon Madam C.J. Walker, political leader Marcus Garvey, civil rights activist W.E.B. DuBois, and R&B Godfather James Brown all saw West Africa as the solution to America’s contradictions.

After repeated attempts to live as an artist and an intellectual in America, Augustus Washington left Hartford for a new life in West Africa in 1853, only seven years after photographing John Brown in his Hartford studio. The 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, his continued abolitionist sentiments, and his frustration over the situation for Black entrepreneurs led Washington to reveal his plans to emigrate to Liberia in an 1851 New York Daily Tribune editorial:

I have been unable to get rid of a conviction, long since entertained and often expressed, that if the coloured people of this country ever find a home on earth for the development of their manhood and intellect, it will first be in Liberia or some other parts of Africa. We must mark out an independent course and become the architects of our own fortunes.New-York Daily Tribune, July 1851

The announcement of his departure was good advertising. His Hartford studio was soon busier than ever so he added space and staff to accommodate the demand.

Before the journey, American Colonization Society (ACS) staff commissioned Washington to produce promotional photographs of Liberia. In 1853, Washington, his wife Cordelia, and their two children sailed from New York to West Africa. They were beneficiaries of a fund the Connecticut legislature approved to encourage colonization. By February, Washington had established a studio in Monrovia, the capital of Liberia. It took some time to perfect the landscape images requested by the ACS, but demand for portraits increased quickly. Limited equipment and delays in ordering supplies led him to develop farmland and rental properties. Augustus Washington divided his investments between artmaking and his small business ventures and saw them all flourish. Washington farmed most of his 1000 acres, ran factories and stores, had a ship for trading, and published the New Era newspaper.

I love Africa because I can see no other spot on earth where we can enjoy so much freedom … I believe that I shall do a thousand times more good for Africa, and add to our force of intelligent men.Augustus Washington, 1854 letter, ACS records

Washington’s investment in photographic supplies for the journey supported his ACS assignment and signaled his interest in new projects. He soon had orders for a series of family portraits and a commission for the official portraits of Liberia’s political leaders. The portraits seem to have been part of a larger project that wasn’t completed.

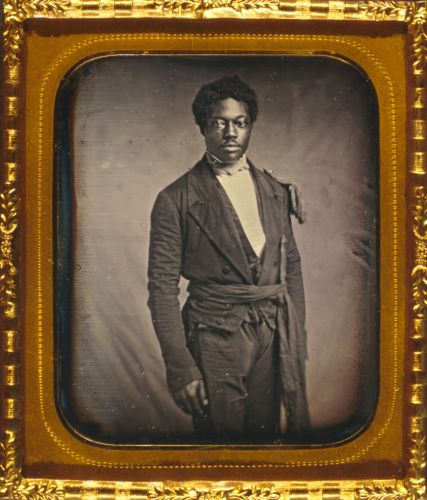

Portraits and Public Office in West Africa

Washington’s 1857 portrait of Chancy Brown, the sergeant at arms of the Liberian Senate—which is in the Library of Congress collection—incorporates elements of the after-hours John Brown portrait with the lighter sensibility of his West Africa portraits. Many of the portraits of Liberia’s senators have the subjects seated in a ¾ turn in the style of Frederick Douglass as elder statesman. Some include a book, scroll, or an arm raised as if holding a flagpole, similar to the pose of John Brown from the previous decade. The photographer’s skill is evident in his adjustments to create flattering light for his brown-skinned subjects, a skill not usually required for his Hartford subjects.

Chancy Brown, a formerly enslaved emigrant from North Carolina, looks at the viewer but manages to hold a bit back. He stands tall, a sword tied with a sash on his left side and an epaulet at his left shoulder. The sash—like John Brown’s cravat—makes it easier to see the summer weight texture of Chancy Brown’s suit as well as the shadows and textures that Washington records. Brown’s pose, self-fashioning, the plain background, and his status as a recently emancipated emigrant imbue the portrait with signs of optimism.

Later in the decade Washington realized his hopes to become active in governance and to hold public office. By 1871 he’d been elected to the House of Representatives and the Senate of Liberia. Four years later, Washington died and the death notice in the African Repository ended with, “Nothing could induce him to return to this country [the United States], having acquired a handsome property and freedom and a home in his ancestral land.”

Augustus Washington’s commitment to teaching and photography traveled with him to Liberia. Though Washington died before he could welcome other West African artists into the profession, photographers, such as: John Parkes Decker, Francis Wilberforce Joaque, Alphonso and Arthur Lisk Carew, all of Sierra Leone, and Alex Agbaglo Acolatse of Togo and Neils Walwin Holm of Nigeria, are all beneficiaries of Augustus Washington’s investment in artmaking, his determination to make a life in West Africa, and the path to citizenship which photography and education created for him.

Appendix

Endnote

- Douglass launched his public career several years after the daguerreotype’s introduction and used photographic portraits—his first from 1841— as a central element in the effort to end slavery. In the 1865 essay “Pictures and Progress” he argued for the educational and motivational potential of photographs.

Bibliography

- Learn about images and abolition

- Read about the Early History of Photography in West Africa from The Met

- Liberian Independence Day from the Connecticut History

- Explore more works by Augustus Washington at the Library of Congress

Originally published by Smarthistory, 05.21.2024, under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.