Initial reactions were mixed.

By Eli Wizevich

History Correspondent

Smithsonian Magazine

Even before there were cars, there was treacherous traffic in Westminster, one of London’s most bustling boroughs, teeming with pedestrians and horse-based transportation.

“Foot passengers have hitherto depended for their protection on the arm and gesticulations of a policeman—often a very inadequate defense against accident,” the London Times wrote on December 9, 1868.

That same day, however, the Times proudly reported on a sparkling innovation newly installed at the intersection outside of Parliament, promising to aid “the regulation of the street traffic of the metropolis, the difficulties of which have been so often commented upon”: the first traffic lights in the world.

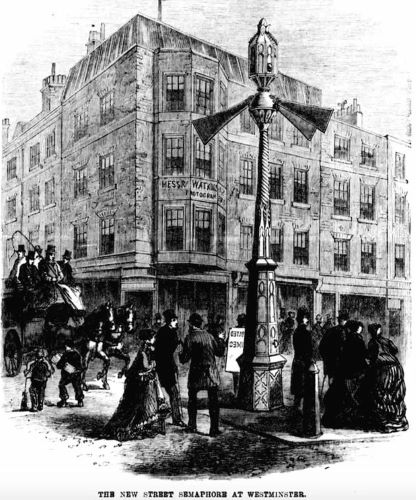

Designed by John Peake Knight, a railway manager from Nottingham, the traffic signal was based on the semaphore system common at rail intersections. Colored arms raised 20 feet above the street would switch between two angles. Fully horizontal meant that oncoming traffic should stop; when the arms were lowered to a 30-degree tilt, traffic could proceed with caution. At night, when the semaphore arms weren’t visible, red and green gaslights signaled stop and go.

Although a policeman still had to stand at the intersections of Great George and Bridge Streets outside of Parliament to operate the signal’s arms and lights, the Times found the first traffic light “extremely simple” and “handsome.”

Not all Londoners were as enamored. One reader of the Daily Telegraph called it a “a monstrous thing resembling a Brobdingnagian lamp-post, afflicted with elephantiasis at the base, and crowned with a huge construction, reminding the spectator … of a pigeon-cote.”

When the light turned, all this individual could see was “a large green eye of the most baleful expression.” Still, they conceded, a traffic signal was, “no doubt, a very good and useful thing.”

The Times predicted that “similar structures will no doubt be speedily erected in many other parts of the metropolis.” But the tenure of the semaphore traffic signal outside of Westminster was short-lived, and the devices had almost no time to proliferate.

Less than a month after it was installed, a gas line connected to the red and green lights exploded, badly burning the traffic warden operating the signal. “The roadway all round the pillar has smelt almost from the time the pillar was put up, as if it were soaked with gas,” the Times wrote with the benefit of hindsight. “Surely the powers that be will take warning.”

The British government dropped the project of gaslit traffic lights and reverted to the old system, reinstating a traffic warden to direct horse-carriage and pedestrian traffic by hand.

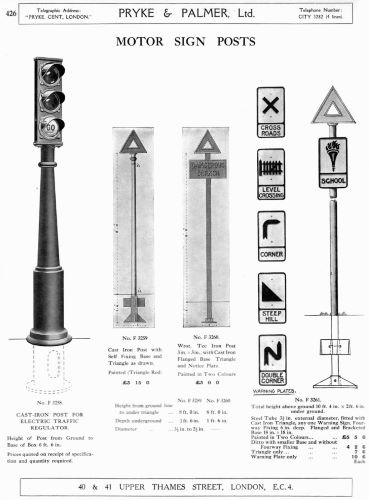

In the meantime, electric stoplights evolved steadily in cities in the United States, where increased automobile traffic joined an already chaotic mix of pedestrians, horses and streetcars. In 1912, a 24-year-old traffic officer named Lester Wire hooked up red and green lights to trolley wires at an intersection in Salt Lake City. Though he never patented his invention, it was copied and proliferated in other cities like Cleveland and Detroit.

Eventually, these American innovations migrated back across the Atlantic, becoming widespread in Britain in the 1920s. But history remembers that the world’s first traffic lights went up at a messy intersection in Westminster, as dangerous, obstructive and ineffective as they might have been.

Originally published by Smithsonian Magazine, 12.09.2024, reprinted with permission under a Creative Commons license for educational, non-commercial purposes.