It was especially the prophetic function that gave Egašankalamma a nationwide significance, and this was actively promoted by Esarhaddon and Assurbanipal.

By Dr. Martti Nissinen

Professor of Religious Studies

University of Helsinki

By Dr. Raija Mattila

Adjunct Professor (Docent) of Assyriology

University of Helsinki

Introduction

The Neo-Assyrian city of Arbela (modern Erbil) was the city of the goddess Ištar, whose temple called Egašankalamma “House of the Queen of the Land,” was the foremost temple of the city and one of the most important Neo-Assyrian temples of Ištar. The temple was a strong nationwide economical centre and the venue of royal festivals after military conquests. Moreover, Egašankalamma was the cradle of Assyrian prophecy. This article explores all cuneiform evidence of the temple of Ištar in Arbela: its decoration, cultic and economical activities, and personnel including the prophets.

Egašankalamma: The Foremost Temple of the City of Arbela

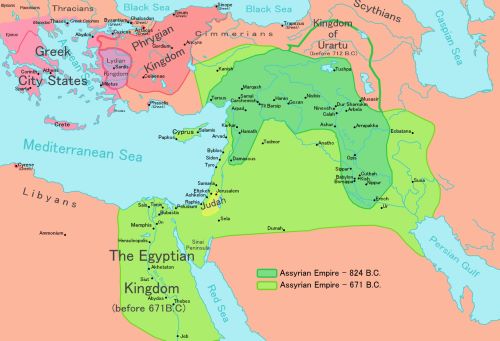

According to cuneiform sources, the city of Arbela/Arbail (as Erbil was called in ancient times) was the city of the goddess Ištar. Most occurrences of name of the city of Arbela in cuneiform texts mention also the goddess and her temple Egašankalamma (é.gašan.kalam.ma/bēt šarrat māti), “House of the Lady/Queen of the Land,”1 which was the foremost temple of ancient Arbela.2 Indeed, it was probably the temple, more than anything, that made Arbela one of the principal cities of Assyria. Ištar of Arbela was not just a local deity, she was known all over the Assyrian Empire as the goddess of prophecy.

The cuneiform sources informing on the temple of Egašankalamma are, unfortunately but not surprisingly, far from being comprehensive. As the temple itself is buried deep under later historical layers of the citadel of Erbil, no archaeological data on the temple is available and information concerning the temple can be only retrieved from ancient textual sources. These, again, are very unevenly distributed, the overwhelming majority of the sources deriving from the late Neo-Assyrian period. Any reconstruction of the history and functioning of the temple is, therefore, most reliable when it comes to the time of the Sargonid kings, but less so concerning earlier periods.

Some important information can nevertheless be drawn from sources dating to the Middle Assyrian period. The first mentioning of Egašankalamma in sources known to us can be found in an inscription of Shalmaneser I (1273–1244) mentioning the rebuilding of this temple and its zigurrat among other temples in other cities.3 Some twelfth-century documents include a list of cultic clothing of Ištar of Arbela4 and a note on the slaughtering of a sheep for the nugatipu of Ištar of Arbela.5 A private dedicatory text to Ištar of Arbela for the life of King Aššur-Dan even mentions the temple:

To the goddess Ištar, the great Lady who dwells in Egašankalamma, Lady of Arbela, his Lady.6

The text is written on a bronze statue found at Lake Urmia, probably originating from Arbela. Dating it to the twelfth century is, of course, only possible if the text refers to Aššur-Dan I and not Aššur-Dan II, who ruled in the late tenth century. Moreover, an inscription of Tiglath-Pileser I refers to Aššur and Ištar of Arbela listening to prayers without mentioning the temple specifically.7

As few as the pre-Neo-Assyrian references to the temple of Egašankalamma are, they at least confirm the existence and functioning of the temple from the thirteenth century BCE at the latest. Moreover, since Shalmaneser I claims to have made “those cult-centers and shrines better than previously,”8 one can assume that he renovated an already existing temple. This is probable anyway, since even older historical records mention the name of the city which probably was never there without a temple.9

The Neo-Assyrian texts beginning with Shalmaneser III are much more informative about Egašankalamma, although even these sources are not quite as specific about the structure and goings-on of the temple as we perhaps would like them to be. The Hymn to the City of Arbela praises the city as a religious center, as “the city of the temple of jubilation”; indeed, as “lofty sanctuary, shrine of the fates, gate of heaven.” The hymn mentions two goddesses, Nanaya and Irnina, but more than anything, it praises the temple of Ištar, referring to the offerings and music performed there and presenting Ištar as being seated on a lion and surrounded by further lions crouching beneath her.10

The Decoration of Egašankalamma

Further information concerning the structure, decoration, and the statues of the temple can be drawn from Neo-Assyrian letters and royal inscriptions. The earliest references to the temple of Ištar of Arbela in the royal correspondence date to the reign of Sargon II, and come from letters written by Amar-ili, an official of the king working in Arbela.11 Amar-ili reports to the king that he has searched for jewels in a temple but has not found any beautiful stones.12 The temple is not specified as that of Ištar, but in another letter13 he reports that the wall behind the image of Ištar has caved in and the master builder has recommended the wall to be removed. Amar-ili is responding to instructions he has received from the king to place a symbol (simtu) behind the image of Ištar and to report back if the wall is leaning. Taken together with a third letter14 by Amar-ili where he reports about clearing away a collapsed palace wall, the evidence may be taken as an indication that the buildings in Arbela including the temple of Ištar had been neglected and were in need of repair.

During the reign of Esarhaddon, the temple was expanded and richly decorated using valuable metals. Esarhaddon describes the work in his royal inscriptions:

[(As for) Egašankalamma, the temple of the goddess Ištar], which is in Arbela, I overlaid (it) with silver (and) gold and made (it) shine like daylight. I had […] made of bronze and installed locks on its gates. I built […] … inside it and surrounded its exterior […]. After the goddess Ištar, my lady, made my kingship greater than that of the kings, my ancestors, [… I] expanded its features.15

Further details are given in another inscription by Esarhaddon:

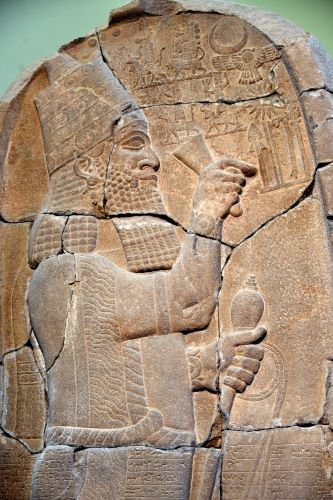

(Esarhaddon …) who plated Egašankalamma, the temple of the goddess Ištar of Arbela, his lady, with silver (zaḫalû) and made (it) shine like daylight – I had lions, screaming anzû-birds, laḫmu-monsters, (and) kurību-genii fashioned from silver and copper and set (them) up in itsentry doors.16

Several features of the temple and its decoration can be deduced from these passages. The temple had valuable overlays of silver and gold and plating in a silver alloy (zahalû). Its entry doors were flanked by lions, monsters and genii made of silver and copper and its gates were equipped with locks. Unfortunately, the passage describing the building itself is very badly preserved but refers to the building of an inner structure of the temple and to surrounding its exterior, possibly by a wall.

The valuable metals used in the decoration of the temple were not left unnoticed by criminals. This we can read in the letters of Aššur-hamatu’a who worked in Arbela under the orders of the king. The letters have been assigned to the reign of Esarhaddon or Assurbanipal but a more precise dating is not possible. Several thefts had occurred in the temple before Aššur-hamatu’a was appointed but the temple personnel had covered up the crimes. Now, Aššur-hamatu’a reports, Nabû-epuš, lamentation priest of Ea, has been caught steeling a golden ornament from the offering table in front of Ištar. The precise nature of the ornament is not known, but it was something that could be peeled off, as the verb used in the letter is “to skin, to peel off.”17

Statues of the king in the temple are referred to in two letters by Aššur-hamatu’a. He reports that the work on the statues of the king for the temple of Ištar of Arbela has been done.18 In another letter19 Aššur-hamatu’a reports that “the royal images stood on the right and left sides of Ištar,” referring either to past practice in general, or to a certain cultic event.

The inscriptions of Assurbanipal, like those of his father Esarhaddon, refer to the bright, daylight-like shine of the temple and add one feature, namely the standards erected in front of the temple: “I made the house of Ištar, my lady, bright as day with silver, gold, and copper. I adorned the standards of the gate of the temple of Ištar with gold and set them up.”20

The standards are shown on a wall relief (AO 19914) from the North Palace of Assurbanipal in Nineveh. The relief depicts a city with a triple-wall situated by a river. The city is clearly identified as Arbela by the caption “uru.arba-ìl” written between the lower and the middle wall. A religious ceremony is depicted in front of a temple that can be recognized as the temple of Ištar by the two round-topped standards of Ištar standing by its façade. Unfortunately, this sole pictorial representation of the Egašankalamma temple is too standardized to give any reliable data concerning the temple’s architecture.

Cultic Activities of Egašankalamma

There are some references to the cultic activity in the temple of Egašankalamma, and one text, The Rites of Egašankalamma, is directly related to it.21 This text is not primarily a description of a ritual, but a mystical-mythical commentary of its meaning, equating the ritual actions with deities, for instance: “The bread which one prepares is Ea, whom he vanquished.”22 Many times, the connection between the myth and the ritual is unclear to the modern reader. Importantly, the rites performed in Egašankalamma are prescribed to be enacted like those in Nippur, which connects the worship in the temple of Arbela with Babylonian cultic traditions. This can be seen also in the prominent role given to Bel/Marduk throughout the text.

Royal inscriptions, in addition to the notes concerning the rebuilding and decoration of the temple, include scattered references to rituals performed in the temple of Ištar in Arbela. In a famous passage, Assurbanipal tells how he, while attending “the festival of the Venerable Lady” (isinni šarrati kabitti) in Arbela in the month of Ab (V), heard about the assault of Teumman, king of Elam. Shocked by this news, he prostrates himself under the feet of the goddess and prays to her, receiving an oracle of salvation from her. This prophetic oracle, beginning with the words “Fear not!,” is followed by a dream seen by a visionary (šabrû) with equally encouraging content.23

The triumph celebrating Assurbanipal’s victory over Teumman was held in Arbela. The religious ceremony depicted on the relief from Assurbanipal’s North Palace in Nineveh (AO 19914, discussed above) shows king Assurbanipal at the gate of the temple of Ištar of Arbela in front of an altar and an offering table holding an upright bow and pouring a libation over the decapitated head of Teumman.24

An administrative text from the time of Sennacherib mentions a due for a qarītu banquet in Arbela,25 and a letter from the Neo-Assyrian period (not dated) reports that Ištar of Arbela has gone up to a qarītu celebrated in Arbela. The letter-writer Marduk-[…] is concerned about a horse that he would like the reluctant chief victuallier to take to Arbela with some sacrificial bread to be delivered to the banquet.26

A prominent cultic sequence between the city of Arbela and the nearby town Milqia is attested in inscriptions of several Neo-Assyrian kings. Shalmaneser III speaks of having celebrated a “festival of the lady of Arbela” after a victorious campaign against Urartu:

Enthusiastically he/I entered Ega[šankalamm]a, the festival of the Lady of Arbela […he/I arranged] in [Mi]lqia. The king joyfully [performed] a lion hunt in Baltil. He felled […, ente]red into the presence of the goddess Ištar with all his booty.27

Due to the damaged state of the text, the sequence of events is not altogether clear, but it seems like the first part of the festival took place in Egašankalamma, from where the ritual action moved to Milqia, a town near Arbela, where there was the “Palace of the Steppe” accompanied by the an akītu-house of Ištar.28 After the celebrations in Arbela and its surroundings, the festival moved to Baltil, the innermost part of the city of Assur, where the king entered ceremonially into the presence of Ištar. Milqia is attested also in letters from the time of Sargon II29 and in the inscriptions of Esarhaddon and Assurbanipal. Even two prophecies from the time of Esarhaddon are likely to refer to the “Palace of the Steppe.”30 Milqia appears as a ceremonial extension of the main temple of the goddess in Arbela. This is where Ištar sojourned when the king was on a military campaign, receiving him after the victorious war. In Milqia, the goddess seems to have been called by the name Šatru, and her stay in the “Palace of the Steppe” symbolized the world of chaos caused by the turmoils of war.

The royal inscriptions and correspondence as well as prophecies pronounced to Assyrian kings make Egašankalamma and its satellite shrine Milqia appear as the venue of royal festivals, especially after military victories. This corresponds well to the character of Ištar of Arbela as “the goddess of warfare, the lady of battle” (ilat qabli bēlet tāḫāzi),31 but poetic and prophetic texts let her appear also as the creator-mother or wet nurse of the king. Assurbanipal calls himself the “product of Emašmaš and Egašankalamma,”32 and when he is praying to Nabû in Emašmaš, the temple of Ištar in Nineveh, the god says:

That gracious mouth of yours that keeps praying to Urkittu. Your body, created by me, keeps praying to me…33 in Emašmaš. Your fate, designed by me, keeps praying to me: “Bring safety into Egašankalamma!”

Your soul keeps praying to me: “Grant Assurbanipal a long life!”34

This poetry not only juxtaposes the two major temples of Ištar as the ones with which the kings had a special relationship. The long life of the king is equated with the endurance and safety (tuqnu) of Egašankalamma.35 This is a recurrent topic also in prophetic oracles, in which the safety and stability (tuqqunu) of the king’s reign is often pronounced by prophets of Ištar of Arbela, who appears as a mother or wet nurse of the king.36 Ištar is not typically known as a mother goddess, but in prophecies and mystical texts this is indeed her role. The two Ištars of Nineveh and Arbela appear as nurses of Marduk,37 and since the king can be called “the Marduk of the people,”38 the goddesses fulfill the same role with regard to the human king. Simo Parpola has plausibly argued that the motherly language used of the goddess has a point of reference in real life: the royal infants since Esarhaddon were brought up as royal infants in the temples of Ištars of Nineveh and Arbela who, through their female devotees, indeed acted as their wet-nurses (Parpola 1997, xxxix–xl). This practice may have been due to the close relationship of Queen Naqia, Esarhaddon’s mother, with these temples.

Egašankalamma as an Economical Centre

An entirely different aspect of the function of the temple of Ištar is documented in non-royal legal texts, which demonstrate the temple’s significant economical agency. Transactions of the temple are attested throughout the Neo-Assyrian period. The documents do not mention the name of the temple but refer to its property and credit as “silver of Ištar of Arbela” or the “first fruits (rēšāti) of Ištar of Arbela” as in the following example from the time of Esarhaddon (date 676-III-11):

Two talents of copper, first fruits of Ištar of Arbela (rēšāti ša Issār ša Arbail),

belonging to Mannu-ki-Arbail (ša Mannu-kī-Arbail),

at the disposal of Šamaš-ahhe-šallim (ina pān Šamaš-aḫḫē-šallim).

He shall pay in Ab (V). If he does not pay, it will incrase by a third.39

The temple of Ištar of Arbela appears often in litigation clauses of legal documents as the place where penalty fees are paid if the contract is broken: the guilty party shall place a specified amount of silver and/or gold “in the lap of Ištar residing in Arbela.” These penalties are ordered in addition to the manifold compensation to the other party of the contract; for example:

Whoever in the future, at any time, lodges a complaint and breaks the contract, whether Balaṭu-ereš or his sons or his grandsons, and seeks a lawsuit or litigation against Mušallim-Issar, shall place 10 minas of silver and one mina of gold [in] the lap of Ištar residing in Arbela, [and shall return the mon]ey tenfold to its owners. He shall cont[est] in his lawsuit and not succeed.40

It is difficult to know how often these clauses actually came into force and how much the temple actually profited from them. The huge penalties handed out to the one who breaks the contract could also be interpreted as a serious deterrent, the purpose of which was rather to minimize the need of enforcing the litigation clauses.

In one document from the time of Sargon II a merchant of Ištar of Arbela is directly lending silver.41 In most cases, like the one quoted above (SAA 6 214), the goddess (that is, the temple) appears as a third party in a document that mentions both the debtor and the creditor. The triangle of the debtor, creditor, and the goddess (that is, the temple) must be based on a long-standing practice of lending, in which the temple of Ištar of Arbela has a well-established agency. The role of the temple in these transactions is not altogether clear, however.42 Is the temple here a financial institution comparable to a bank or a pawn-shop, giving credit to customers?43 If this is the case, what is the role of the person who appears as the one to whom the money is said to belong? If he is the actual creditor, it is very difficult to explain why the money is called “first fruits” of Ištar, implying that its actual owner is the temple.44 Perhaps the actual creditor is the temple and the person mentioned in the document is, rather, a broker or a temple official acting on behalf of the temple.

In addition to the above-mentioned document mentioning a merchant (tamkāru) of Ištar of Arbela as the creditor of a loan, the persons acting in the documents mentioning the “first fruits” of Ištar of Arbela are usually not temple officials or affiliated to the temple in any function, but persons who sometimes seem to be very active in different businesses. One of them, Mannu-ki-Arbail, is a well-known military officer from Nineveh, who is known from a considerable number of transactions and does not seem to have any particular affilitation with the temple Ištar in Arbela.45 The same can be said of the cohort commander Kiṣir-Aššur or of Silim-Aššur, known later as vizier,46 and the other creditors. Therefore, it is not clear how and why these creditors should be acting on behalf of the temple.47 Perhaps they could have been functioning as cedents who act as a middlemen between the debtor and the temple, but it is difficult to see why the temple was using such brokers in its operations and how it would have profited from such a practice. The fact that not all transactions at our disposal mentioning the “first fruits” of Ištar of Arbela derive from the Nineveh archives suggests that the banking business of the temple of Arbela was not restricted to city of Arbela, and the temple had to have representatives in other cities acting on its behalf.

Another (perhaps better) explanation is that the person appearing as the creditor has actually loaned his own money to the debtor who owes the “first fruits” to the temple of Ištar in Arbela. If this is true, then the debtor has not been able to fulfill his obligations to the temple with his own capital but had to borrow it from the creditor. One can only speculate, of course, for what reasons an Assyrian citizen would have had obligations to the temple. The term “first fruits” (rēšāti) refers to offerings, thus rendering the sum of money a compensation for the offering of the first agricultural products of the harvest season, but it may also have developed into a term denoting a certain type of debt without being a payment of specific offerings. Not all debts are called rēšāti, but simply “silver of Ištar of Arbela.” Even in these documents, the creditor and the debtor are named and the temple appears as the third party. However the types of transactions and the role of the temple in them should be interpreted, legal documents make the temple of Ištar appear as a wealthy institution and a significant economical agent even outside the city of Arbela.48

The Personnel of Egašankalamma

As to the temple community and its members, the information is rather scattered, mentioning only a few individuals explicitly affiliated with the temple. The temple steward Aplaya, that is, the temple’s Human Resources official, writes to Esarhaddon or Assurbanipal on problems caused by some exempted temple slaves.49 Of the merchants of the temple, who must have played an important role in the temple’s business, only one anonymous tamkāru is mentioned in the sources. Of the craftsmen of the temple, a weaver (ušpāru) called Bel-issiya is attested already in the time of Adad-nirari III,50 and further evidence comes from the time of Esarhaddon and Assurbanipal, when the weavers of Arbela were active in the city of Kurbail.51 We also know that the temple had scribes (ṭupšarru), and two of them are known by their names: Kandalanu, a temple scribe who, according to the colophon, wrote the Khorsabad King List in the time of Tiglath-Pileser III;52 and Issar-nadin-apli, the foreman of the collegium of ten scribes of Arbela, whose correspondence with the king concerns astrological observations in the time of Assurbanipal.53 These pieces of information connect the temple with scribal and astrological activities.

Perhaps the best known part of the personnel of Egašankalamma consists of its female members. There is evidence of both male and female votaries (lú/mí.maš, however this word might be pronounced, and lú/mí.suhur.lá = kezru/kezertu) dedicated to Adad in Kurbail and Ištar of Arbela from the time of Adad-nirari III,54 and further female votaries are well known from later times. The position of a votary of the temple is somewhat unclear. In the documents from Esarhaddon, the votaries are all female, and they are mentioned either in the context of marriage or divorce or as the property of the temple – not, however, that of Ištar of Arbela. Three Arbela-based votaresses are wives or daughters of a high-ranking Assyrian citizen, all of Egyptian origin. One of the women is not a votary of Ištar but, according to the marriage contract, is to be given as such in case the husband divorces her.55 One woman is a young votaress growing up in the temple and married off by her brother,56 while in third case, the marriage contract indicates she is a votaress even during the marriage.57 Evidently, a woman could have the status of a votary whether or not she was married, and this status brought them institutional protection against arbitrary decisions of their (Egyptian) husbands or brothers. The sources do not reveal more about their agency or their relation to the temple community.

In two further cases, the female votaries are acting as prophets.58 These are the only cases where the votaries have some kind of an agency, and having a prophetic agency does not come as a surprise in the case of Egašankalamma. Prophetic activity in Arbela is documented by oracle texts and, directly and indirectly, in letters.59 Seven out of fifteen Neo-Assyrian prophets known by their personal names are said to come from Arbela, which doubtless indicates their affiliation with the temple of Ištar (see Nissinen 2001, 179–80). Three of them are women: Ahat-abiša, Dunnaša-amur and Sinqiša-amur (the two last-mentioned names may actually belong to one and the same person), and one anonymous female prophet from Arbela is mentioned in a letter. One or two prophets are of uncertain gender (Bayâ, probably a genderwise ambiguous person; Ištar-la-tašiyaṭ, probably male60), and the remaining two are men (La-dagil-ili, Tašmetu-ereš).

Prophetic activity is arguably the feature that is typical of Egašankalamma more than any other Assyrian temple. Ištar of Arbela is the goddess whose words most Assyrian prophets transmit even outside the city of Arbela. Even Ištar of Nineveh, under the name Mullissu, appears as the divine speaker of prophetic oracles, but no prophets are known to be based in her temple in Nineveh or elsewhere. It was especially the prophetic function that gave Egašankalamma a nationwide significance, and this was actively promoted by Esarhaddon and Assurbanipal, who seem to have had a special devotion to this temple.

Conclusion

The available evidence presents Egašankalamma as one of the foremost of Neo-Assyrian temples of Ištar. It was perhaps less prestigious than Emašmaš, the temple of Ištar in Nineveh, which was the capital city of Assyria since Sennacherib, but its significance was well comparable to temples of Ištar in other major Assyrian cities, such as, for instance, the temple of the Lady of Kidmuri in Calah. In all appearances, the temple was a strong economical actor in Assyria, having a nation-wide economical catchment area. The same can be said of its religious significance. Egašankalamma, together with its satellite shrine, the “Palace of the Steppe” in Milqia, was the venue of royal festivals after military conquests, but it probably even served as the place where royal infants were brought up in late Neo-Assyrian times. According to the sources available to us, especially the kings Esarhaddon and Assurbanipal, as well as their (grand) mother, Queen Naqia, had a particularly close personal relationship to the temple. Perhaps at least partly for this reason, Egašankalamma was the cradle of Assyrian prophecy, which made Ištar of Arbela the foremost divine messenger.

(See endnotes and bibliography at source).

Originally published by Advances in Ancient Biblical and Near Eastern Research (AABNER) 1:1 (June 2021, 114-142), DOI:10.35068/aabner.v1i1.789, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.