Barbed wire telephony reveals a dimension of American technological history that developed outside the pathways typically associated with modernization.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Rural Isolation and the Problem of Communication in Pre-Network America

Across the rural United States in the late nineteenth century, communication existed as a fragile thread stretched over vast distances that commercial infrastructure had never reached. Farm families lived with limited access to timely information, relying on mail delivery, local newspapers, or word of mouth. The geographic scale of settlement meant that essential developments in weather, markets, or transportation often arrived too late to be of practical use.¹ This isolation was not the product of neglect alone but reflected the priorities of early telecommunications businesses that concentrated their resources in dense urban markets where profits were more predictable and costs lower.2

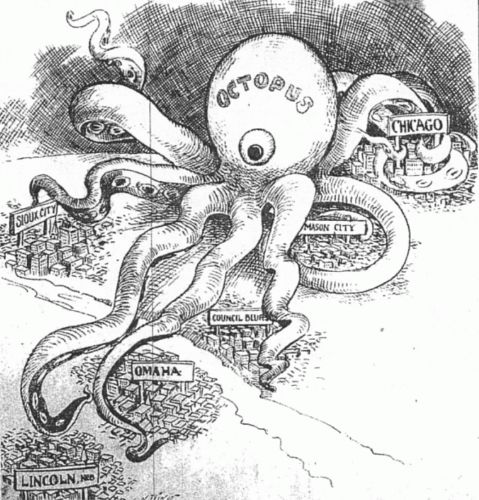

The legal environment contributed its own barriers. For nearly two decades the Bell monopoly exercised exclusive control over much of the telephone’s commercial development, leaving independent firms unable to produce competing equipment until the expiration of key patents in 1894.3 Rural areas were effectively priced out of the network before they even had an opportunity to join it. The monopoly’s structure created a widening divide between those regions incorporated into national communication systems and those left to devise their own solutions.4

Yet the gap between corporate reach and rural necessity did not suppress demand for communication. Instead, it sharpened awareness of the limitations of existing systems. Farmers and ranchers needed access to forecasts, transportation schedules, and emergency contact with neighbors, and many recognized that geography itself required a different model of connectivity than the one devised for cities.5 Scholars of telephone history have emphasized that rural adoption patterns followed their own trajectory, shaped more by local relationships and environmental conditions than by formal corporate design.6 The conditions were therefore set for the emergence of an improvised technological culture in which communities experimented with the infrastructure they already possessed.

As these pressures accumulated, the stage was prepared for the rise of grassroots networks that did not wait for corporate integration. In the absence of formal lines, rural communities turned to the material that stretched across their fence lines and property boundaries.7 What emerged from this moment of constraint and ingenuity was barbed wire telephony, an improvised system built not from commercial infrastructure but from the landscape itself.

Patent Expiration and the Rise of Independent Telephony

The structure of the American telephone industry in the late nineteenth century was shaped by the legal protections surrounding Alexander Graham Bell’s early patents. For nearly twenty years these patents limited who could manufacture telephones and how telephony could develop outside the Bell system.8 The effect was uneven access. Urban centers received the bulk of Bell’s investment, while rural communities were left with little prospect of affordable connection. The patent regime created both technological stagnation for regions excluded from coverage and mounting frustration among farmers who recognized how crucial rapid communication had become for their work.9

This landscape shifted after 1894, when the expiration of Bell’s principal patent opened the field to new manufacturers. Independent companies quickly emerged and produced magneto telephones that were legally free of Bell’s control.10 The change reshaped the rural technological market. Instead of depending on a single firm whose priorities lay elsewhere, farmers could now purchase equipment at lower prices from competing suppliers. These manufacturers, including firms such as Kellogg and North Electric, recognized the needs of rural users and marketed products suited to environments where infrastructure was minimal and technical labor was supplied by the community itself.11

The rapid growth of the independent sector altered the balance of the American telephone system. Thousands of small exchanges and informal associations appeared across the Midwest, Great Plains, and Mountain West, often established long before Bell or its affiliates considered these regions viable.12 The increase in local autonomy did not simply fill a geographic void. It produced a communication culture defined by experimentation, neighborly maintenance, and the willingness to adapt existing materials rather than wait for corporate expansion. Independent systems thrived because rural Americans recognized that connection could serve as a collective good even without national standardization.

By the early twentieth century, the independent movement had become a major force in American telecommunications, and officials acknowledged its scale in federal reports that documented the proliferation of non-Bell exchanges.13 These developments also revealed a structural truth about American telephony: legal constraints had once restricted innovation, but once lifted, they enabled a flowering of local ingenuity that took forms no corporation had predicted. Barbed wire telephony emerged from this moment. It was not a peripheral improvisation but a direct consequence of the economic and legal opening that allowed rural communities to choose autonomy over absence.

Agricultural Infrastructure as Electrical Infrastructure: The Adaptation of Barbed Wire

Farmers across the American West and Great Plains adapted barbed wire to telephony because it already formed the largest continuous metallic network in their environment. Fences stretched for miles across ranches and fields, creating linear pathways that could conduct electrical signals when linked to a basic magneto telephone.14 This repurposing was not accidental. It reflected a practical awareness that commercially installed lines were unavailable and that the landscape itself could be transformed into a tool for communication.15 Barbed wire telephony therefore emerged from a combination of necessity, resourcefulness, and the material abundance of fencing shaped by decades of agricultural expansion.

Early telephone designs supported this type of improvisation. The magneto telephones produced by independent manufacturers after 1894 could operate with minimal infrastructure.16 They required only a simple circuit with adequate tension and continuity, conditions that barbed wire already provided. Technical manuals from companies such as Kellogg emphasized the durability of these systems, noting that they could function on long stretches of open-wire line if properly grounded.17 Farmers discovered that by attaching their instruments to sections of fence wire and creating a return path through a second strand or the earth, they could achieve reliable communication over considerable distances. This compatibility allowed rural communities to integrate telephony without the specialized labor that commercial firms demanded.

Despite these advantages, the system required careful adaptation. Fence posts were typically made of uninsulated wood, and moisture could disrupt the flow of electrical signals.18 Rain created leakage paths that weakened transmission, especially on lines where wire touched damp posts. Farmers developed workarounds that ranged from inserting small pieces of insulating material between wire and post to elevating the wire slightly using nails or staples. These measures were simple yet effective, allowing networks to remain functional in varied weather conditions. Experience taught rural users how environmental factors shaped performance, and they adjusted their construction methods accordingly.

The choice of barbed wire also introduced social and technical challenges. Fences were shared boundaries, and telephony required agreements about maintenance, access, and the handling of accidental breaks.19 Livestock pressure, storms, and routine agricultural work could interrupt the line. Communities responded by establishing informal rules for repairing wire, determining which stretches would be insulated, and coordinating where telephones would connect. The system fostered a form of cooperative engineering in which individuals learned not only to place calls but to maintain the infrastructure that sustained them.

Over time these improvised systems expanded beyond single properties and connected multiple farms. The networks remained rudimentary by urban standards, yet they demonstrated that robust communication did not always require formal infrastructure.20 Their success showed how material conditions, legal freedom after 1894, and rural ingenuity converged to produce a distinctive technological culture. Barbed wire telephony did more than adapt fencing to electrical signals. It revealed how communities could transform everyday materials into tools of connection when excluded from the commercial networks that defined early American modernity.

Community Engineering: Party Lines, Ringing Codes, and Grassroots Governance

As barbed wire networks expanded across adjoining farms, they developed into party line systems that relied on shared access rather than individualized circuits. Farmers used the magneto telephones equipped with hand-cranked generators that produced distinctive ringing patterns, allowing callers to signal specific households despite the communal nature of the line.21 These codes became a central element of rural communication. They were easy to learn, flexible to adapt, and grounded in the cooperative spirit that made informal telephony possible in regions without corporate oversight.22 The simplicity of these practices kept costs low and allowed the technology to spread without formal training or technical supervision.

Shared lines also required social norms that mediated constant exposure to neighbors’ conversations. Party line users could hear the signal for every call on the network, and although etiquette discouraged casual eavesdropping, full privacy was never guaranteed.23 Rural communities therefore developed expectations about when calls should be made, how long they should last, and what constituted acceptable listening behavior. These norms were reinforced through local relationships rather than written rules. They served as a form of communal governance that balanced the open nature of the system with the need to maintain trust among users who depended on one another for repairs, information, and emergency communication.24

Maintenance represented another cooperative dimension of barbed wire telephony. Because the lines ran along fences, they were vulnerable to damage from livestock, storms, and routine agricultural work. Communities learned to coordinate responsibilities, with neighbors agreeing to monitor specific segments and report or repair disruptions before they cascaded across the network.25 Some areas adopted more formal arrangements through farmers’ telephone associations, which issued bylaws describing how repairs would be shared and how costs would be divided.26 These documents reveal a blend of informal local practice and emerging institutional structure, illustrating how rural telephony fostered collective problem-solving that commercial firms had never attempted in these regions.

The governance of rural networks extended beyond technical maintenance and into the rhythms of daily life. Barbed wire systems connected widely dispersed households and enabled forms of social interaction that reshaped community experience.27 Neighbors exchanged local news, organized mutual aid, and circulated weather reports, often using the network as a social commons as much as a tool for communication. The combination of technical improvisation and communal participation produced a distinctly rural telecommunications culture. It functioned because the community agreed to make it function, and because people who were excluded from corporate systems recognized that connection could be built from the materials at hand.

Newspapers, Weather Reports, and Rural Modernity: What These Networks Were Used For

Barbed wire telephone systems emerged in a world where information traveled slowly across rural landscapes, and their earliest users understood that communication could substantially shape agricultural decision-making. Farmers depended on timely reports about weather conditions that influenced planting, harvesting, and livestock management.28 Traditional channels such as newspapers and county agents provided delayed information, but improvised telephone lines offered immediate updates shared among neighbors who monitored storms, frost conditions, or signs of approaching blizzards.29 The speed of exchange mattered. It allowed communities to react collectively to events that could threaten crops or herds, and it created a new sense of temporal coordination within regions that had long moved at the pace of mail and seasonal cycles.

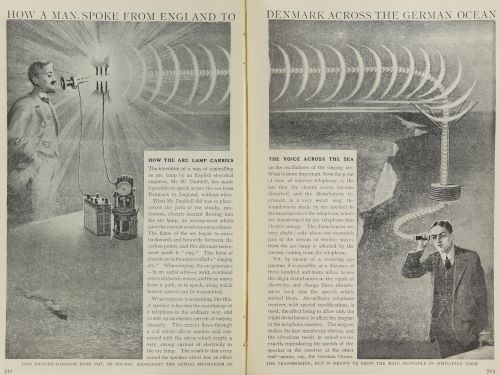

Train schedules formed another crucial category of information transmitted over rural networks. Railroads were the economic arteries of rural America, linking remote communities to markets and supply centers.30 When trains ran late or arrived early, merchants and farmers needed to adapt quickly. Barbed wire telephony allowed station agents or travelers to relay schedule changes to nearby farms, reducing the uncertainty that shaped everyday commercial life.31 This use of improvised lines expanded the functional reach of rail systems beyond towns and depots. It integrated rural families into the logistical operations of a broader economy even before they gained access to commercially installed telephone lines.

Newspapers documented how these systems evolved and how communities recognized their potential. In 1902, The New York Times reported plans by ranchers near Fort Benton, Montana, to establish a rural exchange that would eventually connect every city in the state.32 The article emphasized not only the scale of the project but also the independence with which ranchers approached communication. Such accounts reveal that barbed wire networks were not merely stopgap measures. They represented a confident belief that rural regions could develop their own infrastructure when corporations failed to invest. The Times coverage placed these initiatives within a larger narrative of western development, portraying them as part of a broader movement toward regional self-sufficiency.

Local newspapers across the Midwest and Mountain West echoed these developments by reporting on the everyday uses of improvised lines. Stories from Montana, Nebraska, and the Dakotas described how residents exchanged market prices for grain, livestock, and feed, often relying on telephoned updates that supplemented or replaced the delayed information printed in weekly papers.33 For farmers whose livelihoods depended on rapid shifts in commodity prices, access to immediate exchange data offered a competitive advantage. These accounts show how rural telephony facilitated economic decision-making and reduced the geographic asymmetry between producers and the distant centers where prices were set.

Beyond economic and meteorological information, barbed wire telephony served as a communication bridge that softened rural isolation. Families used the network to share news, coordinate community gatherings, and report emergencies, transforming telephony into a daily instrument of social cohesion.34 Scholars have noted that this pattern of usage differed from urban environments, where commercial telephone service emphasized individual communication.35 In rural areas, improvised systems functioned as communal resources that strengthened local institutions, whether they involved church committees, cooperative associations, or informal neighborhood networks. The telephone became both a practical tool and a symbol of communal interdependence.

Over time the cumulative effect of these uses redefined what modernity meant for rural Americans. Barbed wire networks did not provide the seamless service of commercial exchanges, yet they offered something equally significant. They linked households into expansive webs of information that allowed them to act with greater awareness of environmental, economic, and social conditions.36 The technology advanced not through corporate coordination but through local imagination and necessity. In doing so, it revealed how rural communities could carve out their own forms of modern communication long before they became part of national systems.

Case Studies across the West and Canada

The development of barbed wire telephony varied considerably across the American West, and regional case studies reveal the flexibility of the system as communities adapted it to distinct geographic and economic environments. In Montana, where ranching dominated the landscape, long fence lines created ideal conditions for improvised networks. Newspapers reported that ranchers near Fort Benton joined their properties through miles of wire, forming an early exchange that connected dispersed households and facilitated the rapid sharing of information necessary for cattle operations.37 These efforts reflected the scale of western ranching, where communication across large territories could determine the success or failure of seasonal work. The Montana case illustrates how environmental scale shaped the improvisational character of rural telephony.

Nebraska offered a different pattern of development, grounded more in farming communities than in expansive ranching regions. Chronicling America preserves accounts of farmers who extended telephony along section-line fences, linking homesteads and small towns even before commercial companies appeared in their vicinity.38 In these regions, barbed wire telephony often served as a precursor to organized farmers’ telephone associations. Residents experimented first with fence lines, learned how to maintain circuits, and later formalized their networks with cooperative structures. This progression reveals how local experimentation laid the groundwork for more permanent institutions that continued to operate well into the twentieth century.

The Dakotas presented yet another variation shaped by climate and settlement density. Harsh winters made weather reporting especially critical, and improvised networks enabled families to warn one another about incoming storms or coordinate mutual aid when snow isolated distant farms.39 These systems remained resilient because communities were accustomed to cooperative forms of labor such as barn raising and shared harvesting. Telephony became an extension of existing social structures, reinforcing patterns of neighborly responsibility. Local reports noted that even when commercial companies eventually installed lines in some towns, rural areas continued to rely on fence wire because it remained cheaper and more adaptable to shifting conditions.40

Across the northern border, Canadian prairie communities adopted similar practices. The Manitoba Free Press reported on farmers who connected homesteads through existing fence wire, particularly in regions where settlement patterns mirrored those of the American plains.41 Canadian networks often evolved alongside grain elevator cooperatives and other rural associations that depended on coordinated communication for market timing and transportation logistics. The success of these systems demonstrates that barbed wire telephony was not an isolated American phenomenon but part of a broader North American response to the challenge of rural isolation during a period of rapid agricultural expansion.

These regional examples reveal a coherent pattern grounded in local autonomy, environmental adaptation, and the willingness to transform agricultural infrastructure into communication technology. Communities in Montana, Nebraska, the Dakotas, and the Canadian prairies demonstrated that effective telephony did not depend solely on commercial investment or standardized engineering.42 Instead, the success of each network emerged from the shared ingenuity of residents who recognized that the materials already present on their land could serve as the foundation for a new form of connection. These case studies therefore contextualize barbed wire telephony as both a technological and cultural phenomenon shaped by the specific needs of rural North America.

Persistence into the Mid-Twentieth Century: Why the System Survived

Barbed wire telephony persisted long after commercial companies expanded their presence in rural America because it remained inexpensive, locally controlled, and well suited to communities that valued autonomy. Cooperative associations grew rapidly in the early twentieth century, yet many households continued to rely on improvised lines because they required minimal investment and used materials already embedded in the agricultural landscape.43 Historical surveys conducted by the Interstate Commerce Commission documented the uneven spread of commercial service during these decades, noting that independent rural exchanges and informal systems still served large territories that corporations had not prioritized.44 The persistence of barbed wire networks therefore reflects the structural gap between rural needs and commercial incentives.

The resilience of these systems was also a product of their technological simplicity. Early magneto telephones could function reliably on open-wire circuits with limited maintenance, and users understood how to repair the lines when storms or livestock caused damage.45 Archival records from the Kansas Historical Society show that many cooperatives incorporated fence-line telephony into their operations even when they adopted more standardized equipment. Their bylaws and meeting minutes reveal an enduring preference for solutions that could be managed locally without dependence on distant providers. This culture of autonomy made it possible for improvised systems to coexist alongside more formal exchanges for decades.

Institutional archives from the Telecommunications History Group in Denver preserve evidence that some barbed wire networks continued into the 1950s and 1960s, particularly in mountainous or sparsely populated regions where the cost of installing new infrastructure remained high.46 These records include photographs, association documents, and oral histories that describe how fence-line telephony adapted to changing circumstances. Even as commercial exchanges replaced many independent systems, a number of communities retained their older networks because they remained functional and familiar. The endurance of these systems demonstrates that rural telephony evolved through practical choices rather than abrupt technological replacement.

Scholars have noted that the survival of barbed wire telephony into the mid twentieth century reflects a broader pattern in rural communication, where users adopted new technologies at their own pace rather than in response to national trends. Rural telephone usage followed distinct social and economic trajectories that often differed from urban models.47 The continuation of fence-line systems illustrates this divergence. They persisted not as relics but as working solutions shaped by local priorities, environmental constraints, and the cooperative practices that had defined rural communication since the earliest experiments with improvised telephony.

Decline, Replacement, and Historical Memory

The decline of barbed wire telephony began as rural electrification and standardized telecommunications infrastructure expanded across the United States in the early and mid twentieth century. Electrification introduced new electrical noise that interfered with the low-voltage magneto systems used on fence lines, making improvised telephony less reliable than insulated commercial circuits.48 As power lines spread across rural regions through federal programs and cooperative initiatives, households increasingly confronted disruptions that their earlier systems could not easily overcome. Commercial exchanges and rural telephone cooperatives offered more stable service, drawing many communities away from improvised networks even when the older systems remained technically usable.

The spread of insulated copper wire and pole-mounted lines further accelerated this transition. These materials provided consistent transmission quality and required less local oversight than fence-line installations.49 Cooperative records show that many associations shifted gradually from open-wire networks to standardized equipment during the 1930s and 1940s, often aided by federal financing that incentivized modernization. Users recognized that the newer systems reduced the maintenance burden that had long accompanied barbed wire telephony. Improvements in switchboard technology and the availability of professional repair services also encouraged rural communities to adopt infrastructure that aligned with national technical standards.

Despite these changes, barbed wire telephony did not vanish quickly. Institutional archives preserve evidence that remnants of these networks persisted in some regions well into the postwar decades. The Telecommunications History Group documents rural communities that retained segments of improvised lines because they continued to function or because users valued the independence they provided.50 These records, which include oral histories and photographs of surviving installations, show that the system’s decline was gradual rather than abrupt. It followed the rhythm of local priorities, economic resources, and the practical realities of replacing one working technology with another.

Historical memory has played a significant role in shaping how barbed wire telephony is understood today. Museums such as the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History preserve early telephones and exhibit the creative forms of rural communication that emerged in the absence of corporate investment.51 Curators emphasize the ingenuity of farmers who transformed everyday materials into tools of connection, framing these networks as part of a broader narrative about American technological adaptation. This preservation ensures that barbed wire telephony remains more than a footnote in telecommunications history. It stands instead as a testament to rural innovation and the capacity of communities to design their own communication systems when excluded from the nation’s developing technological infrastructure.

Conclusion: Improvised Technology and Democratic Communication

Barbed wire telephony reveals a dimension of American technological history that developed outside the pathways typically associated with modernization. Rural communities created systems that reflected their own needs and priorities rather than the commercial logic of national corporations. The networks emerged from practical challenges rooted in geographic isolation and the uneven expansion of early telecommunications.52 They demonstrated that rural Americans were not passive recipients of technological change but active participants who adapted available materials to overcome structural exclusion. In this sense, barbed wire telephony stands as a case study in democratic innovation, shaped by local choices rather than centralized planning.

The durability of these improvised systems underscores the strength of the cooperative practices that supported them. Farmers and ranchers did more than repurpose fencing; they created communication networks that rested on shared labor, mutual trust, and community-based governance.53 Even as commercial systems spread across the countryside, barbed wire telephony persisted because it expressed values deeply rooted in rural life, including autonomy and collective responsibility. The eventual decline of these systems reflected changes in national infrastructure rather than the failure of the technology itself. Their disappearance marked a shift toward standardized communication, yet it also closed a chapter on an early form of rural ingenuity.

Today the historical memory of barbed wire telephony survives through museum collections, archival materials, and scholarly accounts that document how communities forged connection from the landscape they inhabited.54 These records preserve an important narrative about technological creativity in regions that commercial firms once overlooked. They show that the development of American telephony was not a single unified process but a mosaic shaped by divergent local experiences. Barbed wire networks were part of that mosaic, and their legacy endures as a reminder that innovation often arises far from the centers of industry, emerging instead from the imagination and resourcefulness of ordinary people.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Claude S. Fischer, America Calling: A Social History of the Telephone to 1940 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), 63–70.

- Richard R. John, “Recasting the Information Infrastructure: The Growth of the Telephone System,” Business History Review 69, no. 1 (1995): 9–11.

- Robert MacDougall, The People’s Network: The Political Economy of the Telephone in the Gilded Age (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), 42–45.

- John, “Recasting the Information Infrastructure,” 19–23.

- Fischer, America Calling, 71–76.

- Fischer, America Calling, 77–82.

- MacDougall, The People’s Network, 112–117.

- MacDougall, The People’s Network, 42–45.

- Fischer, America Calling, 63–76.

- U.S. Patent Office, Bell Patent Expiration Records, 1894; see also MacDougall, The People’s Network, 46–48.

- Kellogg Switchboard and Supply Company Catalog, 1902, Smithsonian Libraries; North Electric Company Manual, 1912, Smithsonian Libraries.

- Fischer, America Calling, 77–82.

- Interstate Commerce Commission, Telephone Statistics of the United States, 1907–1912.

- Ronald R. Kline. Consumers in the Country: Technology and Social Change in Rural America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000.

- MacDougall, The People’s Network, 112–117.

- Fischer, America Calling, 77–82.

- Kellogg Switchboard and Supply Company Catalog, 1902, Smithsonian Libraries.

- Kline, “Consumers in the Country,” 23-55.

- Kline, “Consumers in the Country,” 23-55.

- Christopher H. Sterling, ed., Encyclopedia of Radio and Telecommunications History (New York: Routledge, 2003), 72–74.

- Kline, “Consumers in the Country,” 23-55.

- Fischer, America Calling, 77–82.

- Fischer, America Calling, 82–85.

- Kline, “Consumers in the Country,” 23-55.

- Kline, “Consumers in the Country,” 23-55.

- Farmers’ Cooperative Telephone Association Bylaws, 1905–1930, Kansas Historical Society.

- Lorie Emerson, “A Brief History of Barbed Wire Fence Telephone Networks.” Lorieemerson.net.

- Fischer, America Calling, 71–76.

- Fischer, America Calling, 77–82.

- Emerson, “A Brief History of Barbed Wire Fence Telephone Networks.”

- Emerson, “A Brief History of Barbed Wire Fence Telephone Networks.”

- The New York Times, “Montana Ranchers to Build Telephone Exchange,” August 10, 1902.

- Nebraska State Journal, 1905–1910; Montana Record Herald, 1902–1908, via Chronicling America.

- Fischer, America Calling, 82–85.

- Fischer, America Calling, 85–90.

- Emerson, “A Brief History of Barbed Wire Fence Telephone Networks.”

- The New York Times, “Montana Ranchers to Build Telephone Exchange,” August 10, 1902.

- Nebraska State Journal, 1905–1910, via Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

- Montana Record Herald, 1902–1908, via Chronicling America.

- Kline, “Consumers in the Country,” 23-55.

- Manitoba Free Press, 1900–1920 reports on rural telephony.

- Emerson, “A Brief History of Barbed Wire Fence Telephone Networks.”

- Sterling, Encyclopedia of Radio and Telecommunications History, 72–74.

- Interstate Commerce Commission, Telephone Statistics of the United States, 1907–1912.

- Kansas Historical Society, Farmers’ Cooperative Telephone Association Records, 1905–1930.

- Telecommunications History Group (Denver), Rural Telephony Collection, archival photographs and association documents.

- Fischer, America Calling, 85–90.

- Smithsonian National Museum of American History, Electricity Collection, rural telephone materials and interpretive notes.

- Kansas Historical Society, Farmers’ Cooperative Telephone Association Records, 1905–1930.

- Telecommunications History Group (Denver), Rural Telephony Collection, archival photographs and oral histories.

- Smithsonian National Museum of American History, Electricity Collection, exhibit documentation on rural telephony.

- Fischer, America Calling, 63–70.

- Kline, “Consumers in the Country,” 23-55.

- Smithsonian National Museum of American History, Electricity Collection; Telecommunications History Group (Denver), Rural Telephony Collection.

Bibliography

- Brooks, John. Telephone: The First Hundred Years. New York: Harper & Row, 1976.

- Emerson, Lori. “A Brief History of Barbed Wire Fence Telephone Networks.” Lorieemerson.net.

- Farmers’ Cooperative Telephone Association. Records and Bylaws, 1905–1930. Kansas Historical Society Archives.

- Fischer, Claude S. America Calling: A Social History of the Telephone to 1940. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992.

- Interstate Commerce Commission. Telephone Statistics of the United States. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1907–1912.

- Kellogg Switchboard and Supply Company. Catalog. Chicago: Kellogg Switchboard and Supply Co., 1902. Smithsonian Libraries.

- Kline, Ronald R. Consumers in the Country: Technology and Social Change in Rural America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000.

- MacDougall, Robert. The People’s Network: The Political Economy of the Telephone in the Gilded Age. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013.

- Manitoba Free Press. Winnipeg, Manitoba. Rural telephony articles, 1900–1920.

- Montana Record Herald. Helena, Montana. Rural telephony reports, 1902–1908. Chronicling America: Library of Congress.

- Nebraska State Journal. Lincoln, Nebraska. Rural telephony reports, 1905–1910. Chronicling America: Library of Congress.

- North Electric Company. Instruction Manual. Cleveland: North Electric Co., 1912. Smithsonian Libraries.

- Smithsonian National Museum of American History. Electricity Collection. Rural telephony exhibits and catalog materials.

- Sterling, Christopher H., ed. Encyclopedia of Radio and Telecommunications History. New York: Routledge, 2003.

- Telecommunications History Group. Rural Telephony Collection. Denver, Colorado. Archival photographs, oral histories, and association documents.

- U.S. Patent Office. Bell Patent Expiration Records. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Patent Office, 1894.

- The New York Times. “Montana Ranchers to Build Telephone Exchange.” August 10, 1902.

Originally published by Brewminate, 12.11.2024, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.