Is his appeal less about the power and complexity of his prose and more about the view of him as a perennial underdog?

By Dr. Scott Peeples

Professor of English

College of Charleston

Introduction

Edgar Allan Poe, who would have turned 214 years old on Jan. 19, 2023, remains one of the world’s most recognizable and popular literary figures.

His face – with its sunken eyes, enormous forehead and disheveled black hair – adorns tote bags, coffee mugs, T-shirts and lunch boxes. He appears as a meme, either sporting a popped collar and aviator shades as Edgar Allan Bro, or riffing on “Bohemian Rhapsody” by muttering, “I’m just Poe boy, nobody loves me” as a raven on his shoulder adds, “He’s just a Poe boy from a Poe family.”

I’m just a Poe boy & nobody loves me.

— Miss Kitty (@Cerridwensheart) October 31, 2022

He’s just a Poe boy from a Poe family. pic.twitter.com/Ad6ciZ0X1I

Netflix has sought to capitalize on the writer’s popularity, recently releasing the mystery-thriller “The Pale Blue Eye,” which features Poe as a West Point cadet, where he spent less than a year before being court-martialed. Netflix also has a Poe-inspired miniseries, “The Fall of the House of Usher,” set to be released sometime in 2023.

But as a Poe scholar, I sometimes wonder whether Poe’s appeal is less about the power and complexity of his prose and more about an attraction to the idea of Poe.

After all, Poe’s most famous literary creations tend to be unsympathetic villains. There are psychopaths who perpetuate seemingly motiveless murders in “The Black Cat” and “The Tell-Tale Heart”; protagonists who abuse women in “Ligeia” and “The Fall of the House of Usher”; and characters who exact cruel, fatal revenge on unwitting victims in “The Cask of Amontillado” and “Hop-Frog.”

The degenerate characters whose perspectives Poe invites readers to inhabit don’t exactly align with a cultural moment characterized by the #MeToo movement, safe spaces and trigger warnings.

At the same time, the conception of Poe the writer seems to tap into a cultural affection for outsiders, nonconformists and underdogs who ultimately prove their worth.

A Character Assassination That Misfires

The idea of Poe the underdog began with his death in 1849, which was greeted by a cruel notice in the New York Tribune: “This announcement will startle many, but few will be grieved by it.”

The obituary writer, who turned out to be Poe’s sometime friend and constant rival Rufus W. Griswold, claimed that the deceased had “few or no friends” and proceeded with a general character assassination built on exaggerations and half-truths.

Strange as it seems, Griswold was also Poe’s literary executor, and he expanded the obituary into a biographical essay that accompanied Poe’s collected works. If this was a marketing ploy, it worked. The friends that Griswold claimed Poe lacked rose to his defense, and journalists spent decades debating who the man really was.

During Poe’s lifetime, most readers encountered his work through magazines, and he was rarely well paid. But Griswold’s edition went through 19 printings in the 15 years after Poe’s death, and his stories and poems have been endlessly reprinted and translated ever since.

Griswold’s defamatory portrait, along with the grim subject matter of Poe’s stories and poems, still influences the way readers perceive him. But it has also produced a sustained reaction or counterimage of Poe as a tragic hero, a tortured, misunderstood artist who was too good – or, at any rate, too cool – for his world.

While translating Poe’s works into French in the 1850s and 1860s, the French poet Charles Baudelaire promoted his hero as a kind of countercultural visionary, out of step with a moralistic, materialistic America. Baudelaire’s Poe valued beauty over truth in his poetry and, in his fiction, saw through the self-improvement pieties that were popular at the time to reveal “the natural wickedness of man.” Poe struck a chord with European writers, and as his international stature rose in the late 19th century, literary critics in the U.S. wrung their hands over his lack of appreciation “at home.”

Poe’s Underdog Story Takes Off

By the turn of the 20th century, the stage was set for Poe to be embraced as the perennial underdog. And Poe often did appear on stage around this time, as the subject of several biographical melodramas that depicted him as a tragic figure whose lack of success had more to do with a hostile cultural and publishing environment than his own failings.

That image appeared on the silver screen as early as 1909 in D.W. Griffith’s short film “Edgar Allen Poe.” With Poe’s wife, Virginia, languishing on a sick bed, the poet ventures out to sell “The Raven.” After meeting rejection and scorn, he manages to sell his manuscript and returns home with provisions for his ailing wife, only to find that she has died.

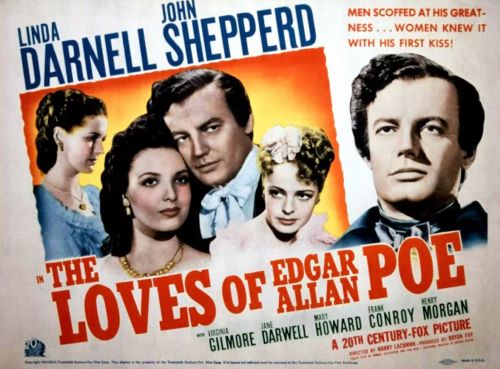

Later films also depict Poe as being misunderstood or underappreciated in his lifetime. A wildly inaccurate biopic, “The Loves of Edgar Allan Poe,” released in 1942, ends with a voice-over commenting, “…little did [the public] know that the manuscript of ‘The Raven,’ which he tried in vain to sell for $25, would years later bring the price of $17,000 from a collector.”

In real life, while an early draft of “The Raven” was declined by one editor, Poe had no trouble selling the poem, and it was an immediate sensation.

But here “The Raven” becomes a stand-in for Poe himself, something dark and mysterious that, according to legend, people in Poe’s time failed to appreciate.

Poe is an obscure writer and amateur detective in the 1951 film “The Man with a Cloak,” which ends with a saloonkeeper allowing the rain to wash away the ink on an IOU that Poe gave him. On the reverse side of the note is a manuscript of the poem “Annabel Lee,” as its bearer declares, “That name’ll never be worth anything. Not in a hundred years.”

Of course, the audience watching this film almost exactly 100 years after Poe’s death knew better.

The Most Interesting Plants Grow in the Shade

Which brings us to “The Pale Blue Eye,” in which Henry Melling portrays Cadet Poe, an outcast with a keen crime solver’s intellect. In a refreshing change, this younger Poe is not a tortured artist or a haunted, brooding figure. He is, however, picked on by his peers and underestimated by his superiors – yet again, an underdog viewers want to root for.

In that sense, the Poe in “The Pale Blue Eye” fits well with his contemporary image, which also permeates the early episodes of “Wednesday,” Netflix’s Addams Family spinoff set at Nevermore Academy that’s chock full of Poe references.

The headmistress of Nevermore Academy – a Hogwarts-like school for outcasts – refers to Poe as “our most famous alumni,” which explains why the school’s annual boat race is the Poe Cup and why there’s a statue of Poe guarding a secret passage.

The delightfully antisocial protagonist, Wednesday, played by Jenna Ortega, is an outcast among outcasts – the Poe figure at a school whose name evokes Poe. In one scene, a sympathetic teacher urges her not to lose “the ability to not let others define you. It’s a gift.” She adds, “The most interesting plants grow in the shade.”

When John Lennon sang “Man, you should have seen them kicking Edgar Allan Poe” in “I Am the Walrus,” he didn’t have to say who was kicking him or why. The point was, Poe deserved better; the most interesting plants do grow in the shade, unlovely and unloved.

And that’s exactly why so many people – aspiring writers and artists, but also everyone when they’re lonely and misunderstood – see a little bit of themselves in the weary-but-wise image of Poe.

Originally published by The Conversation, 01.19.2023, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution/No derivatives license.