Urban renewal incubated a growing commercial sex industry, which in turn fueled a new demand for human labor.

By Dr. Christopher Paolella

Professor of History

Valencia College

Introduction

In this essay, I argue that the socioeconomic changes of the twelfth and early thirteenth centuries laid the groundwork for permanent alterations in human traff icking patterns later in the thirteenth century. In this period, the networks slowly transitioned from supplying predominantly agricultural labor with legally enslaved victims to supplying predominantly sex labor with legally unenslaved victims (largely through illicit sales, coercion, and abduction) in Western Europe, north of the Alps and Pyrenees. The growth in monetary exchange, the popular internalization of Latin Christian identity, and the growing sense of spiritual community among Christians, all caused slavery as a means of compelling agricultural production to decline, but slavery itself nevertheless lingered in other forms, such as domestic slavery, and as a cultural and a legal category.

The revitalized monetary economy also encouraged an urban renewal across Western Europe that would incubate a growing commercial sex industry, which would in turn fuel a new demand for human labor. Thus the contours of late medieval human trafficking in Western Europe were sculpted in the twelfth and early thirteenth centuries, but the results of this shift in demand from agricultural labor to sex labor would only come to historical light in the decades that followed. Moreover, human trafficking continued to evolve in Northern Europe, Eastern Europe, and throughout the Mediterranean world. We must not, then, view Western Europe in isolation, because its socioeconomic changes would have far-ranging consequences for long-distance trafficking patterns elsewhere. Therefore, we will complete our surveys of the Northern and Southern Arcs and then consider the high medieval pivot.

Late antique and early medieval human trafficking networks intensified and abated over the course of time. We see, for example, an increase in long-distance, regional, and local trafficking activity in the late Empire, an abatement of long-distance trafficking and a continuation of regional and local trafficking between the sixth and eighth centuries, followed by an intensification of local, regional, and long-distance trafficking over the course of the ninth, tenth, and eleventh centuries. The networks’ relative independence of one another, the mutability of the roles of trafficking victims within medieval economic systems, and the overlap between slaver and trader, all allowed human trafficking networks to adapt to the many different socioeconomic and political environments in which they operated. However, the twelfth and thirteenth centuries witnessed socioeconomic changes that would profoundly affect human traffickers and their victims in succeeding centuries.

Earlier centuries had already seen the blending of the casati servi (the ‘hutted slaves’ who lived in their own homes, as opposed to domestic slaves who lived in or near the domiciles of their owners), serfs, and the freeborn poor into a larger but ill-defined ‘servile’ socioeconomic group. While there continued to be important legal distinctions among slaves, serfs, and freeborn peoples, the differences among these legal categories in terms of agricultural labor and financial obligations had blurred. Intermixed marriages of different legal status, as well as the detachment of labor obligations from personal status and their reattachment to property status, meant that serfs, slaves, and freeborn might have similar obligations towards their lord, depending on the legal status of their property. The crux of the change in social relationships of power was the transition from servile versus freeborn to servile versus noble.1

Over the course of the twelfth century, greater political stability encouraged the expansion of the monetary economy, which in turn encouraged lords to commute agricultural labor obligations to rents paid in produce and in coin. Those of servile status, excluding domestic slaves, increasingly lived as de facto tenants even if they remained de jure unfree.2 I must stress that the relationship between the growth of monetary exchange and commercial markets and the decline of slavery as a means of compelling agricultural production were peculiar to Western Europe, north of the Alps and Pyrenees, in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. In no way did commercial development inevitably lead to the end of slavery, as the Roman Empire, later medieval Italy and Byzantium, or the early modern transatlantic slave trade unequivocally demonstrate.

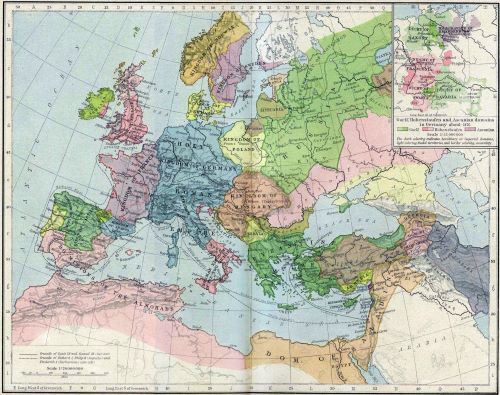

The growth of the monetary economy encouraged the process of medieval urbanization already underway in the twelfth century. Greater political stability and improvements in agricultural technology led to a major population increase during the eleventh and twelfth centuries that fueled urbanization and trade, which led to increased demand for coinage and access to it. At the same time, the twelfth century witnessed the growing importance of religious identity vis-à-vis local and ethnic identities among elite and ordinary Western European Christians alike.3 The result of these socioeconomic changes was the decline of agricultural slavery across much of Western Europe. Jeffrey Flynn-Paul, for example, has argued for the perfection of ‘slaving’ and ‘no-slaving zones’ between the twelfth and the thirteenth centuries, in which both secular and religious authorities within Christendom and the Dhar al-Islam were able to protect their borders from external raids, exert more internal control over their own merchants, and enforce prohibitions on enslaving coreligionists. The net result was to push the zones of enslavable populations outwards into Eastern Europe and into Sub-Saharan Africa. Although the general picture Flynn-Paul paints of greater social, political, and religious cohesion across the twelfth and thirteenth centuries in Western Europe appears accurate, I argue that these ‘slaving’ and ‘no-slaving’ zones were by no means perfected but were instead quite porous, mainly because those prohibitions were loosely interpreted and haphazardly enforced.4

These general trends of twelfth-century economic growth and increasing internal political stability are well known from the work of such scholars as Marc Bloch, Georges Duby, Dominique Barthelemy, and Norman Pounds,5 and trafficking networks were not immune to these changes. Agricultural production remained the major sector of the European economy until the Industrial Revolution, and as the unfree part of the agricultural labor force gradually shifted from chattel and hutted slaves to landed servile tenants, the demand for slave bodies decreased in Western Europe, and long-distance trafficking networks began to dissipate.

Across the Northern Arc, the long-distance trafficking routes fractured and regionalized, coinciding with the waning of the Viking Age and the end of Scandinavian dominance across Northern Europe. However, across the Southern Arc of the Mediterranean trafficking networks remained robust, fueled by the growth of Italian cities such as Genoa, Venice, and Pisa, and later by the growth of Aragonese cities such as Barcelona. These long-distance trafficking networks in the Mediterranean supplemented and joined with local and regional networks, which – rooted as they were in their own immediate sociopolitical circumstances – were able to thrive.

Yet it is easy to make too much of the ebbing of slavery in Western Eu-rope over the course of the twelfth century. We must bear in mind several important caveats to this general trend. First, historians do not agree on the chronology; the disappearance of slavery was neither uniform nor complete.6 Second, slavery may have disappeared from agricultural production, but it lingered in the domestic setting of wealthy households across Europe. Third, slavery remained a legal category in places such as Scandinavia into the fourteenth century, and a legal as well as socioeconomic status in the Mediterranean basin into the early modern period. Finally, the end of slavery in Western Europe in agriculture did not mean an end to servitude. The definitions of ‘servitude’ were constantly evolving, but servitude itself remained a fixture in European social, economic, and political life.

If the demand for slave bodies in agricultural production had gradually evaporated across much of Western Europe by the end of the twelfth century, how then did trafficking networks endure? In part, they persisted by adapting in step to widespread changing socioeconomic conditions, such as by localizing or regionalizing.7 Trafficking networks survived in Western Europe, albeit in attenuated forms, partly by supplying the demand for domestic slaves, especially the ancillae, female household slaves.8 However, a new source of demand for labor was emerging within European cities and towns. Amid the widespread urban renewal, commercial sex grew and prospered. To be sure, prostitution had never disappeared from Europe. What had changed, starting in the latter half of twelfth century, were its scope, scale, and permanency. The change, in other words, was structural, as commercial sex transitioned into a commercial sex industry. Prostitution gradually became more organized through socioeconomic structures such as brothels and prostitution rings. As it grew and organized, a web of interrelated roles beyond client and sex worker – which included religious and secular authorities, property owners, procurers, and traffickers – developed in tandem. Prostitution evolved into an industry that became a feature of urban life, and that industry turned in part to human traffickers in order to meet its labor needs and thus fuel its growth.

The Late Medieval Northern Arc

As the twelfth century wore on, long-distance trafficking networks across the Northern Arc of Europe gradually dissolved. I suspect that this process was primarily the result of concurrent changes in agricultural production in Western Europe: because Scandinavian traffickers were so enmeshed in the slave trade across Western Europe, they would also be acutely affected by the flagging demand for bodies during the twelfth century. However, the demise of the Northern Arc was likely also in part the result of the dwindling of Scandinavia’s political power and of its hegemony across the northern waters of Europe in the twilight of the Viking Age. Yet here we must confront the limitations of the sources, which for twelfth-century slave trading are scarce: thus my suspicions, however measured, must nevertheless be a priori in order to bridge the chasm between the late Viking Age and the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

We are on firmer footing in the thirteenth century, particularly when we consider Henry of Livonia’s Chronicon (c. 1180–1227). Henry evinces a strong interest in military affairs throughout his work, including detailed descriptions of battles, equipment, strategies, and techniques. From these details we gain more than glimpses of the raids that led so many people to the auction block; we can piece together a vivid picture of raiding and slaving that reduced whole communities to blood, ash, and chains. While much of the activity he chronicles takes place in the first decades of the thirteenth century, Henry describes trafficking networks among Baltic peoples that must have existed during the twelfth century before the incursion of Christian forces. It is difficult to believe that regional and local trafficking in the Baltic inexplicably ended in the twelfth century and then suddenly revived with the arrival of Western European Christian observers in the early thirteenth.

Henry of Livonia describes eastern local and regional trafficking networks throughout his Chronicon. These networks centered on the ports of the Gulf of Riga, but extended outwards northeast into Estonia, east into Livonia and Russia, and southeast into Lithuania. We have evidence of late twelfth-century trafficking activities running along north–south routes between the Lithuanian and Livonian peoples around the Gulf of Riga circa 1180,9 and a particularly successful raid by southern Lithuanians into northern Estonian territory in 1205 netted an impressive collection of Estonian captives, which according to Henry ‘numbered over a thousand.’10 East–west trafficking operations also centered on the Gulf ports, particularly Riga, and ran into the Russian interior towards Novgorod via the hinterlands of Gerzike (Jersika, Latvia).11 Farther west in the ports of the Gulf of Riga, traffickers boarded ships, and fluvial and terrestrial routes transitioned into marine routes. The Isle of Oesel and Visby on Gotland served as major Baltic networking hubs from which regional routes extended southwest to the northern shores of Germany, and westwards into Sweden and Denmark.12 Upon the Baltic Sea, the terms ‘merchants,’ ‘slavers,’ ‘raiders,’ and ‘pirates’ describe more the immediate activity of these sailors, and less their identity or career.

Henry ’s Chronicon has so many references to slaving raids that their descriptions become formulaic, so it is difficult to say for certain how any one raid occurred, yet major underlying patterns emerge from the dozens of incidents he records. For example, religion was a major, although unreliable, social fault-line, and oftentimes German Christians and their Baltic Christian allies conducted raids against their pagan neighbors and vice versa. Religious identity created some cohesion in the fractious politics around the Baltic Sea in the early thirteenth century, however, no predominant power emerged in the area during this time, and both Christians and pagans were as likely to be raided as to raid. While the German Christians appeared to be the dominant military force, they were hamstrung by their small numbers and relied on their native coreligionists to make forays against their pagan neighbors, who in turn added to the webs of trafficking by passing their captives through their own local and regional political and economic ties. Among the numerous parties involved in the ongoing conf licts, women and children were the primary targets for capture.13

Henry describes nearly identical patterns of behavior in these raids, and given his keen interest in military matters, I suspect that his observations accurately represent common raiding strategies of parties whether pagan or Christian and regardless of ethnic identity. A basic slave raid began with a mustering of forces including members of allied groups. After a journey of several days – a timeframe that itself indicates the frequency and extent of localized trafficking – the raiding party splintered and each subgroup then followed a different route through various villages in the immediate area, effectively creating a dragnet. Raiders focused on the villages, but they also monitored the roads for refugees in f light. Once in the villages, homes and fields were burned creating a panic within the local community. Raiding parties usually, although not always,14 killed the men, and carried off the women and children, livestock, and moveable wealth, but in some cases the women and young boys were also butchered and the girls alone were carried away.15 After several days in the field, the various parties regrouped at a predetermined location to divide the captives and spoils among themselves before returning to their own lands.

In general, the strategy outlined above was extremely effective, to the point that it was adopted on all sides for raids upon the others. However, because raiding parties had to be large enough to splinter into sizable subgroups capable of raiding multiple settlements simultaneously, these parties were occasionally observed on the roads and rivers in time for the locals to scatter. The survival strategy of the villagers used local knowledge of the terrain to evade or outlast the invaders. In some cases, they attempted to f lee on alternative roads. Since children, the elderly, and the infirm were also in their numbers, oftentimes villagers relied less on mobility and more on stealth for their escape. Familiar with the neighboring woodlands, they commonly resorted to f light to the forests, but this tactic was also predictable and raiding parties that found a village deserted would often search the nearby woods, with varying degrees of success.16

If we now turn our gaze westwards from the Baltic to the region between the North and Baltic Seas, we have evidence for human trafficking in the thirteenth-century Skåne law codes from southwest Sweden, which stipulate, ‘If a freeborn man comes into slavery, because he is captured and afterwards sold, and he is killed, then his relatives and nearest kinsmen have the right to take full compensation for him and give to the master who owned him as much of the compensation as the dead man cost him when he bought him.’17 The possibilities of descent into slavery via raid or war and then entry into trafficking networks form the circumstances for this particular statute. Yet besides attesting to the presence of slave trading in the early thirteenth century in the heart of Scandinavia (and reminding us that men, too, were still swept up in trafficking webs), the law gives us few details about the extent, volume, personnel, or structures of thirteenth-century trafficking. In fact, Ruth Mazo Karras has argued that when we consider the extant sources for late medieval Scandinavia, literary and legal, the supply of foreign slaves into Scandinavia seems to have dwindled to little more than periodic acquisitions of captives.18

Slavery itself continued in Scandinavian society into the fourteenth century, presumably through internal recruitment such as hereditary slavery, penal enslavement, and debt slavery, although this last type appears to have increasingly become an extra-legal social condition in Scandinavia as time went on. Importantly for this study, however, Scandinavia never relied on slavery as the basis of its economic output, but instead treated slavery as a legal, social, and cultural category.19 This means, then, that Scandinavian societies alone could not perpetually absorb both periodic external influxes and continual internal recruitment of slaves. If traffickers across the Northern Arc were to remain in business then they had to export their human cargo, so as the demand for slave bodies in Western Europe declined, then so too did trafficking in the North Sea region. Thus I contend that the distinction between dwindling trafficking networks in western areas of the Northern Arc and the thriving local and regional networks of the eastern Northern Arc strongly suggests that by the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries, the overall decreasing volume of commerce in human bodies could no longer sustain permanent long-distance trafficking networks across the whole of the Northern Arc. Instead, in the east where human trafficking remained economically viable, local and regional networks continued to operate independently of their western counterparts, and with the waning demand in western markets the socioeconomic ties among the networks dissolved. The long-distance networks of the northern waters of Europe had fractured and regionalized.

The Late Medieval Southern Arc: Long-Distance Trafficking Networks

If long-distance trafficking routes were dwindling across Western Europe and the Northern Arc during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, new long-distance routes were opening in the Mediterranean, fueled by the growth of northern Italian cities such as Genoa, Pisa, and Venice. As the economic centers of activity in the Italian peninsula gradually shifted from Amalfi, Bari, and Taranto in the south to the northern cities of the Po River plain, trafficking networks responded accordingly, and the Po River grew into the dominant Italian artery for human traffickers throughout the Late Middle Ages.

Starting in the early thirteenth century, Italian merchants established a lucrative trade route supplying the Eastern Mediterranean with slaves from the Caucasus region of the Black Sea and Eurasian steppe via the Bosporus. While the first Black Sea slaves reached Genoese markets in 1233, after the reclamation of the throne of Constantinople by Greek emperors in 1261, Eurasian slaves began to pour into Genoa, such that by the early fourteenth century they accounted for the majority of Genoese slave imports.20 In Venice, despite official prohibitions, by the end of the thirteenth century Black Sea slaves were entering Venetian markets for local purchase or traf-f icked farther beyond into the heart of Italy.21

Italian outposts at Caffa in the Crimea and Tana, at the mouth of the Don River on the Sea of Azov, became cities unto themselves by the latter half of the thirteenth century. While control over Caffa changed hands between the Genoese and Venetians during this time, the Genoese and the Pisans gained over their bitter rivals, the Venetians, in the aftermath of the collapse of Latin rule in Constantinople in 1261. The new Greek Byzantine Emperor, Michael VIII Palaiologos (r. 1261–1282), rewarded the Genoese for their support by exempting them from imperial customs, duties, and taxes according to the Treaty of Nymphaion. The Venetians, however, would regain the favor of the Emperor several years later, in part due to imperial anxiety over Genoese economic dominance. By late July of 1268, Venice had reacquired rights to free trade in the Black Sea and in Byzantine ports throughout the Empire. Michael’s successor, Andronikos II Palaiologos, granted the Venetians the right to establish mercantile enclaves in Constantinople itself in 1285, and in 1332, the Venetian Doge, Francesco Dandolo, and Emperor Andronikos III Palaiologos concluded a treaty that granted Venetians in Constantinople safe passage and free trade, as well as rights to establish further trading settlements across the Byzantine Empire, in exchange for annual payments to the imperial treasury.22

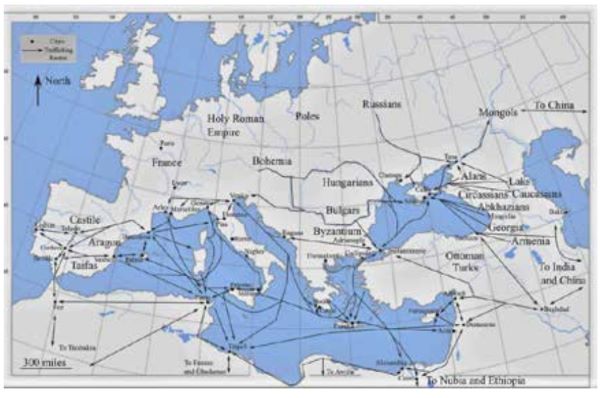

Having secured commercial rights and privileges from Byzantium and bolstered by economic connections with the Mongols, Italian traff icking operations now reached deep into the heart of the Eurasian steppe, reflected in the growth of Genoese Caffa as the major Levantine slaving center. Venice remained a power based in Tana, and in Soldaia by 1288, even during the Genoese administration of the former between 1332 and 1471. Italian influence continued to expand in Black Sea ports such as Trebizond during the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries.23 Iris Origo has shown through extensive archival research in northern Italy that these Black Sea ports attracted not only Italian merchants, but also traders from across the Africa-Eurasian world.24 Through these international ports, Genoese and Venetian commercial connections stretched north into Russia and the Baltic, east into the Caucasus, Armenia, Anatolia, and the Eurasian steppe, south into Syria and Egypt, and west into Provence, Catalonia, and Corsica, according to notary deeds of sale. These trade networks also traff icked Mongol youths, Russian and Circassian girls and young women, Georgians, Alans, Laks, and Armenians, and apparently a little girl of Chinese origin named Charatas (orta ex generatione Cathayorum), from the east into Caffa and into Tana via the Don River.25 Networks running east-west moved Caucasians from the east, and Hungarians and Bulgarians from the west into Black Sea ports. These webs brought together victims newly acquired in raids and kidnappings, and those who had been purchased by traff ickers in the markets of Daghestan on the western shores of the Caspian. Moreover, local Tartar, Circassian, Abkhazian, and Mingrelian peoples appear to have will-ingly sold their children to Italian traders operating out of Caffa and Tana, when deprivation and hunger among their peoples became unbearable.26

In the early 1260s, the Genoese took advantage of imperial patronage by allowing foreign merchants to pay a head tax for the embarkation of each slave in their harbors, and by hiring out their ships to other slavers such as the Venetians. However, as the prof its became apparent, the Genoese themselves quickly began taking a proactive role in trafficking, especially south towards Egypt.27 With Michael Palaiologos as their imperial patron, the Genoese eventually enjoyed the protection of both the Byzantine Empire and the Mamluk Sultanate. In 1281, Michael Palaiologos and Qalawun, the Sultan of Egypt (r. 1279–1290), concluded a treaty that guaranteed safe passage for slavers operating between the Black Sea and Alexandria via the Bosporus and Byzantine territory, and in exchange for this extended protection, Genoese traffickers agreed to pay duties to the Emperor.28

Demand for Turkish slaves in Egypt had been robust for centuries.29 Muslim forces in Egypt had recruited Turkish slaves into their ranks since the ninth century, and the Fatimids (969–1171) continued this practice in order to supplement their enslaved Ifriqiyan black infantry with enslaved Turkish cavalry in their conquest of Egypt in 969. Nasir-i Khusraw (c. 1004–1077), visiting Cairo 80 years later in 1049, reported that the conquest had become something of a local legend; the inhabitants of the city believed that the enslaved Turkish cavalry alone had numbered 30,000. The problems with medieval numerical estimates aside, clearly a large force of enslaved foreign cavalry had left its imprint upon the collective memory of the city. In his own visits, Nasir observed a large contingent of slave-soldiers, whom he called Abid al-Shira and estimated they numbered about 30,000, in the forces of the Egyptian sultan.30 The successors of the Fatimids, the Ayyubids (1171–1260), continued to import Turkish slaves in order to mitigate the military threat of the Crusaders. These Turkish and later Circassian boys, collectively known as mamluks, were captured or purchased from other slave dealers in the area of the Black, Azov, and Caspian Seas by Byzantine, Muslim, and Italian slavers, who then shipped the children via the Bosporus and Dardanelles, or herded them along overland routes via Eastern Anatolia, the Caucasus, and then Azerbaijan, down to merchant enclaves (funduqs) in Alexandria, or into the major slave market of Cairo, the Khan al-Masrur.31 In the slave markets of Alexandria and Cairo, Muslims, Byzantines, and Italians and their cargoes of Eurasian bodies intermingled with Sub-Saharan bodies brought north along major North African caravan routes, and Eurasian steppe peoples, brought to Egypt via land routes that ran south through Anatolia and Ayyubid Syria, or south from the Caucasus and through Azerbaijan, and thence into Ayyubid Syria via the Euphrates.32 By 1420, the Mamluk Sultanate was purchasing over 2000 slaves a year from Genoese slavers operating out of Caffa, according to contemporary accounts.33

Trafficking networks between the Black Sea and Egypt proved enduring. Even after the Ottomans severed the Italian slaving networks with the conquests of Constantinople in 1453 and Caffa in 1474, trafficking nevertheless continued much as it had in previous centuries. Following the Ottoman conquest of Egypt in 1516, Sultan Selim (r. 1512–1520) left the Mamluk governing infrastructure largely intact, and even appointed a rebel Mamluk, Khayr Bey (d. 1522), as his viceroy in the province. With Mamluk administrative infrastructure preserved, the recruitment of slave boys from the Black Sea region continued into the early modern period.34 Meanwhile, Florence and Venice were becoming increasingly dependent upon slave labor for their state-owned war galleys in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and Italian traff ickers thus adapted to the loss of the Black Sea by shifting their slaving activities towards North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa, and the lands of the Ottoman Turks in order to supply that demand for labor.35

Long-distance networks also traveled from east to west from the Crimea and the Levant into Italy. The vast majority of those trafficked into northern and central Italy were Mongols,36 but Caucasian, Bulgar, Romanian, Hungarian, North African, Nubian, and Ethiopian peoples are all attested in deeds of sale preserved in the archives of Genoa, Florence, and Venice. In fact, the northern half of Italy experienced a resurgence of domestic slavery beginning in the second half of the fourteenth century. The expansion of Italian trade networks and the subsequent increase in the volume of trade between Italy and the East over the preceding two centuries were imperiled by the depopulation that followed the Black Death of 1348. Merchant households were threatened not only by the loss of heirs, but also by the loss of servants, assistants, and the labor force, which had been hollowed out by the pestilence. By 1363, the Priors of Florence recognized that the demographic pressure was not easing, and on 2 March of that year they decreed that the city would accept the unlimited importation of domestic slaves of both sexes from eastern lands, provided the enslaved were not Christian. The revival of Italian domestic slavery and the subsequent growth of local, regional, and long-distance trafficking soon spread from Florence to cities and towns across Tuscany and the Po River Valley.37

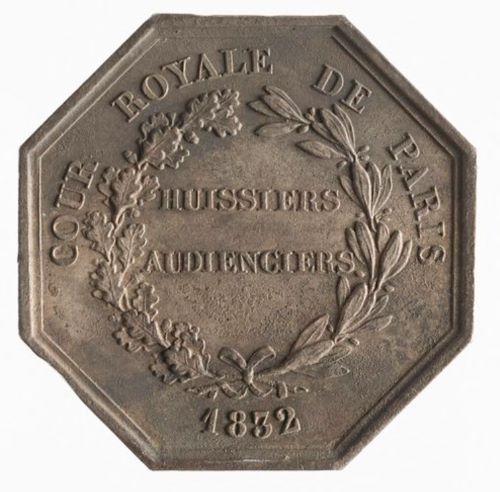

In Venice and Genoa, trafficking had never ceased. Municipal statutes regulated the number of slaves that their galleys could carry, which was determined by the size of the vessel in the case of Genoa and by the number of crewmembers aboard ship in the case of Venice. The statutes of the Officium Gazariae of Genoa set down that a ship with a single deck could carry up to 30 slaves, with fifteen additional slaves permitted per additional deck. Thus a two-decker was allowed up to 45 slaves, and a three-decker up to 60. In addition, each merchant on board was allowed a single male slave.38 The Venetian statutes stipulated that no ship embarking from Tana should carry more than three slaves per crewmember, and Venetian authorities levied a tax of five ducats per head imported into Venice. Based upon annual tax revenue totals, Origo has calculated that between 1414 and 1423, a period of nine years, over 10,000 people were sold at auction by auctioneers, known as sensali or sensari, in the Venetian markets of the Rio degli Schiavoni and the Rialto, or in private homes of locals who bought and sold slaves from traffickers or directly from other slaveholders.39 Michael Balard gives similarly high totals for Genoa: 5000 people in 1380 alone. Over the course of the fifteenth century, the Genoese numbers began to drop: 2000 in 1405, 1750 in 1450, and 800 in 1472. This decline was precipitated by a variety of issues including war with Venice in the late fourteenth century, disruptions to slaving networks caused by the incursions of Tamerlane (1336–1405), problems associated with the Genoese tax auctions system under the French administration of the city in early fifteenth century,40 and the loss of Black Sea markets with the fall of Constantinople in 1453. The victims sold each year in the markets of Venice, Genoa, Florence and other Italian cities, were then distributed by local and regional traffickers, as well as private owners, across the northern half of Italy.

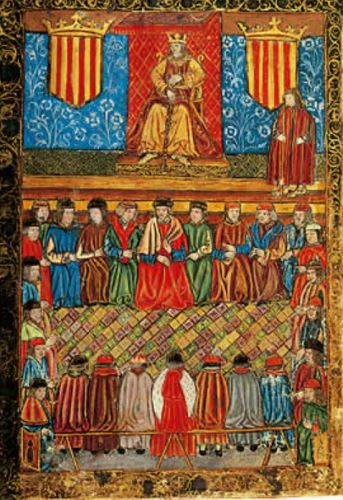

As the thirteenth century gave way to the fourteenth, the Aragonese and Catalans began to compete and occasionally cooperate with the Italian long-distance and regional slaving networks as they expanded out of the Western Mediterranean and ventured farther east. Fueled by the activities of mercenary companies operating in Byzantium during the early fourteenth century, Aragonese and Catalan human trafficking activities quickly developed into complex pan-Mediterranean networks.

Initially, the companies of Catalan mercenaries, based in Gallipoli under the leadership of Roger de Flor (1267–1305) and others, limited their kidnapping, raiding, and slaving to Turkish settlements in Anatolia, the Aegean islands, and mainland Greece. Greek populations were certainly harried, their property was seized, and their wives and daughters became targets of mercenary aggression, but there is little indication that the Greek Christian population had become enslaved. Nevertheless, Catalan violence upon the native Greeks was endemic, which in turn strained Byzantine–Catalan relations. The situation changed in April 1305 when Roger de Flor was assassinated, and the Catalans blamed the Byzantines for his murder. Thereafter, until 1310 when the Catalans departed the Empire, the Greek Christian population became ‘the other,’ and therefore vulnerable to raiding, kidnapping, and enslavement.41 The mercenaries adopted the banner of Saint Peter for their own, which signaled both that the Greek Christians were now considered schismatics, and therefore targets for reprisals, and that the mercenaries were now politically aligned with the Byzantine emperor’s nemesis, Charles of Valois (1270–1325).42

According to the contemporary Greek historian Georgios Pachymeres (c. 1242–1310), the Catalans depopulated the lands west of Constantinople as they killed or exiled the native population, and then sold many of the inhabitants along with other moveable wealth later in the environs of Adrianople. The Catalan commander-turned-chronicler, Ramon Muntaner (1265–1336), noted the bustling activity in the slave market of Gallipoli after Catalan military activities. As the mercenary companies moved farther west in their war against the Empire, they settled on the peninsula of Cassandreia in 1309, and expanded their slaving activities into Greek Christian settlements in Thessaloniki and the monastic communities of Mount Athos.

What is noteworthy is the remarkable speed at which victims were moved from the war zone to the markets. In a raid against the Alans in 1306, the Catalans sold the women they had captured in the environs of Adrianople only a few days later, according to Pachymeres. According to Muntaner, after a skirmish against an Italian force from Thessaloniki, the captives were sold the very next day in Gallipoli’s slave market. Moreover, although many of these victims ended up in the markets of southeast Europe near the Black Sea, the Catalans also linked with Venetian and Genoese traffickers and sold them into regional networks centered on the Venetian colony on Crete. In several cases the mercenaries cut the Italian middlemen out entirely and sold their victims directly to Venetian residents of Candia.43

The speed and geographic scope of Catalan trafficking indicate that the mercenaries cooperated with other actors in the slave trade in order to funnel victims from the war zone into trafficking webs as quickly and as efficiently as possible. We know, for example, that Majorcan slavers bought victims from the mercenaries and then sold them in the markets of Famagusta on Cyprus.44 On Crete, the case of a Greek woman, Keranna, illustrates well this complex and organized trade. A Catalan traff icker named Boredanus recommended Keranna for purchase to a resident of Candia named Nadal Rier. Rier, as it turns out, acted as a slave retailer who agreed to then sell Keranna on to a certain Michael of Negroponte. When the deal was struck, Boredanus did not then transport Keranna to Nadal himself; instead he sent her to Crete via a fellow Catalan, a merchant of Barcelona named Berenguer Espayol.45 Thus Keranna passed from her initial owner (Boredanus), to her trafficker (Espayol), on her way to her initial purchaser in Candia (the retailer Rier), who was to then sell her to her f inal owner (Michael of Negroponte).

The Late Medieval Southern Arc: Local and Regional Trafficking Networks

It is easy to forget that Mediterranean long-distance trafficking networks grew alongside local and regional networks, the latter of which operated in the Western, Central, and Eastern Mediterranean. Generally, regional trafficking operations competed successfully with long-distance traffickers throughout the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. However, many of those regional operations gradually lost ground to long-distance competitors over the course of the latter half of the fourteenth century and beyond. Local and regional trafficking never died out, but they were increasingly subsumed under larger operations that were supported by more powerful polities, such as the Ottoman and Habsburg empires.

In the Western Mediterranean, local and regional trafficking networks operated across religious lines with greater frequency as the Italians undertook the conquest of the Tyrrhenian islands, and as the Reconquista gathered momentum down the Iberian Peninsula. In the twelfth century, traffickers exported victims of the island conquests from Corsica to Pisa and from Sardinia to Genoa.46 Those captured in Iberia during the incessant fighting of the Reconquista, especially women and children, were then shipped to northern Italy, North Africa, or to the Tyrrhenian islands, or were sold locally across the religious divide.

Slavers worked on both sides of the Castilian frontier, selling captured Christian women into Muslim households and vice versa, or transporting the captives overland to Barcelona for transmarine shipping.47 In fact, for many warriors on the frontier between Christian and Muslim lands, slaving became an important source of income. Known as almogavers, these opportunistic warrior-slavers were found among both Christian and Muslim peoples and each raided the lands of the other, as well as those of their own coreligionists on occasion, not for conquest but for loot. Sometimes they participated in formal military actions organized by local authorities, and at other times, they engaged in simple banditry. These almogavers cooperated with merchants who bought the enslaved from the warriors on site of the battle or raid and then organized the transport of the victims to seaports on the Mediterranean coast of Iberia, which indicates regular, organized communication and cooperation among raiders, slavers, and merchants along the Iberian frontiers.48 Merchants from Barcelona, for example, were selling Iberian and North African Muslim captives in the markets of Genoa, and paying a head tax of five denari in the markets of Pavia in 1128.49

Among the Tyrrhenian islands, 55 years later in 1183, Ibn Jubayr (1145–1217) remarked upon regional trafficking networks in Sardinian markets as he traveled from Iberia to Alexandria aboard a Genoese merchant vessel. A fellow Muslim passenger who spoke Latin had gone with the Latins (Rumi) to collect supplies for the travelers and came back to report that he had seen, ‘a group of Muslim prisoners, about 80 between men and women, being sold in the market. The enemy [Latin Christians] had just returned with them from the sea-coasts of Muslim countries.’50 Considering the ongoing warfare in Iberia between Christian and Muslim forces and the proximity of the Tyrrhenian islands to Muslim North Africa and Iberia, we can reasonably presume that many if not most of these victims were taken from the Western or Central Mediterranean – Iberia, the Maghreb, and Tunis. In Pisa, regional commercial trade networks, which included slaving, were described in the late twelfth-century Liber de Existencia Riveriarum, which articulates regional trafficking webs in the Western Mediterranean. The Existencia Riveriarum was intended as a navigational itinerary that spanned the Tyrrhenian Sea from the Italian coast south to North Africa, and west across to Iberia, incorporating the Tyrrhenian islands and their ports. The text includes detailed descriptions of ports, estimated distances between ports, descriptions of coastlines, and natural and artif icial landmarks across the Western Mediterranean basin, all in order to aid mariners in spatial recognition and navigation.51

As long-distance trafficking grew between Italy and the Levant in the latter half of the twelfth century, regional networks in the Western Mediterranean among Italy, Iberia, and North Africa diminished. Pisa, and later Florence, concluded several peace treaties with Muslim Iberia and North Africa in an effort to reduce piracy and open conflict in the Western Mediterranean, and as a result, regional traff icking abated. Dur-ing the relative calm, two Christian orders, the Order of Mercy and the Trinitarians, sent envoys to Muslim Iberia and North Africa to redeem as many coreligionists as possible. The areas in which the orders operated were not chosen at random. Iberia, North Africa, and the Alborán Sea that lay between them, had maintained traditions of terrestrial and marine raiding across the religious frontier since the eleventh and twelfth centuries, and which would later continue into the sixteenth century and beyond.52 The numbers are impressive: in 1199, the Trinitarians ransomed 186 Christians in Morocco with funds donated by Pope Innocent III (r. 1198–1216). In 1202, they ransomed 207 Christians for sale in Muslim Valencia. Between the years 1202 and 1211, the Trinitarians ransomed between 94 and 340 of their coreligionists each year in ports such as Granada, Barcelona, Valencia, and Tunis. The Trinitarians were aided by the foundation of the Order of Mercy, otherwise known as the Mercedarians or the Knights of Saint Eulalia, in 1218 specifically for the purpose of ransoming or otherwise rescuing Christians enslaved in Muslim lands.53

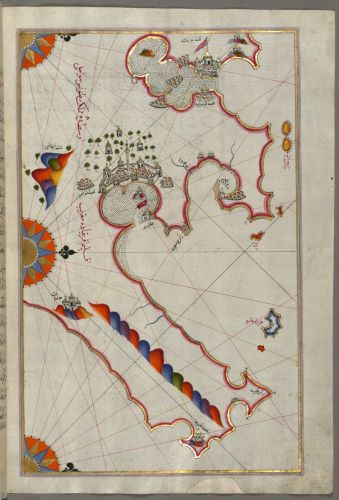

The peace would not last forever, but regional trafficking had diminished, nonetheless, in the face of long-distance competition that had grown in the interim between Italy and the East, whose activities were burdened by no truce and bound by no terms. Those Italian long-distance networks continued to expand out of Italy south and westwards now in the fourteenth century, gradually engulfing formerly regional operations as the earlier peace treaties were forgotten or ignored. We can observe this process of gradually expanding trade networks in the navigational charts produced in Genoa and Venice during this time. For example, in Genoa, the navigational chart, Carte Pisan, which was produced in the late thirteenth century before 1291, depicts the entirety of the Mediterranean basin along with the Black Sea (although the Black Sea portion is heavily damaged),54 and the Genoese cartographer Pietro Vesconte (fl. 1306–1321), based primarily in Venice, incorporated the Black Sea and the Levant into his Mediterranean depictions.55

The charts illustrate the wider world across in which thirteenth- and fourteenth-century trade networks once again operated. Fourteenth-century Ethiopian slaves arrived in Italy via a circuitous route across North Africa into Muslim Iberia, and thence on to Italy via Barcelona and Majorca, or to Italy from Tunis via Sicily, Sardinia, and Corsica. Meanwhile, Italian merchants transported victims who had originated on the Eurasian steppe around the Black, Azov, and Caspian Seas into the Western Mediterranean to Majorca and Barcelona via Italy.56

International politics would make the return of those formerly independent regional trafficking networks that had operated in the twelfth-century Tyrrhenian and Alborán Seas impossible. Even as Italian long-distance trafficking waned in the f ifteenth and sixteenth centuries with the fall of Constantinople and territorial expansion of the Ottomans, regional Muslim raiding and trafficking operations based in the Maghreb were brought under the Ottoman banner in the early sixteenth century. On the Christian side meanwhile, regional Christian raiding and trafficking operations based in Spain were gradually brought under the banner of the Habsburgs, a process that began in the 1530s and continued to the end of the sixteenth century.57 As Western Mediterranean raiding and pillaging across the religious divide took on imperial undertones, the local and regional trafficking webs that relied upon such raiding patterns also came to reflect and to be understood as local expressions of a wider clash of empires. In effect, international politics ensured that the fracturing of long-distance trafficking networks across the Northern Arc would not be replicated later across the Southern Arc.

In the Central Mediterranean, regional trafficking networks revolved around two principal areas: northern Italy and Tunis in North Africa. Trafficking into northern Italy continued across the ethnic and linguistic divides between the Roman Christian Latins of Venice and the Orthodox Slavs of the Balkans, across the Adriatic Sea at the mouth of the Narenta River (Neretva). For example, slaving between Venice and medieval Ragusa (Dubrovnik) across the Adriatic increased over the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, largely in one direction – from Ragusa to Venice – until the Ragusans outlawed the foreign sale (although not the domestic sale) of slaves in 1416. Demand for Balkan women in northern Italy, who were intended for domestic duties and sexual labor, caused slave prices across Dalmatia to spike, and Susan Mosher Stuard contends that regional slaving, primarily between the Balkans and Italy, eventually priced enslaved Balkan women out of local markets beginning in the early decades of the fourteenth century.58 Yet even as regional traffickers exported Dalmatian women from Ragusa to Venice, Venetian and Slavic slavers imported Qipchaq Turks, Mongols, and Circassians from the markets of Crimea and Constantinople into Ragusa, as regional and long-distance trafficking networks met and overlapped.59 Thus despite the fact that the Venetians controlled Caffa for nearly 60 years in the thirteenth century and had access to slaves from across Eurasia via Soldaia and Tana throughout the Late Middle Ages, regional traffickers in the Adriatic were nevertheless able to both compete and cooperate with long-distance Venetian operations well into the fifteenth century.

As the Ottomans pushed through Eastern Europe into the Balkans, local Slavic traffickers established connections with the conquerors across ethnic and religious divides. Much like the Ayyubids and Mamluks, the use of slave soldiers to bolster the ranks of the Ottoman military in the reign of Murad I (c. 1362–1389) provided traffickers with a powerful demand for bodies.60 The Balkans provided the manpower for the Janissaries, which possibly reflected the difficulty in obtaining Qipchaq Turks during the late fourteenth century in the wake of the plague, or the threat that Christian Constantinople still posed to Muslim slaving networks in the Eastern Mediterranean. The number of Janissaries grew slowly through the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, from roughly 1000 during the fourteenth century to about 6000 by 1475. However, due to ongoing hostilities in the next century with the Habsburg and the Safavid dynasties, Janissary recruitment increased dramatically to an estimated 23,000 by the 1590s.61 For the peoples of the Balkans, then, regional trafficking networks squeezed their populations on both sides, as young women and girls were trafficked westwards towards northern Italy via Venice and young boys eastwards towards Constantinople, all in ever increasing numbers.

South of Europe on the shores of North Africa, Tunis was growing into a major commercial center for trading and slaving at the junction between the western and eastern halves of the Mediterranean basin, and by the middle of the fourteenth century the city had approximately 100,000 residents. Tunis was among the first North African ports to welcome Christian traders from Southern Europe. Merchants from the Western Mediterranean ports such as Marseilles and Barcelona, and from northern Italian city states such as Pisa, Genoa, and Venice, were all granted safe harbor and allowed to conduct business in protected enclaves within the city.

Tunis connected with Tripoli via overland routes that hugged the shore of the Mediterranean Sea. By way of Tripoli, regional Tunisian trafficking networks linked with long-distance trafficking routes that piggybacked on major trade and pilgrimage routes, traversing the desert from Timbuktu to Egypt on the way to Mecca and Medina. Traffickers moved east and west along these trans-Saharan pilgrimage routes, before leaving them and branching northwards towards Tripoli via Fezzan or towards Tunis via Ghat and then Ghadames, or else continuing eastwards towards Cairo via the major slave market at Awjila, which fed the markets of Cairo and Tripoli with Sub-Saharan bodies from Ethiopia and beyond.62

Meanwhile, in the Eastern Mediterranean during the twelfth, thirteenth, and fourteenth centuries, the Peloponnese ports of Modon and Coron, Famagusta on Cyprus, and Candia on Crete, were the nodes in insular webs of local and regional trafficking activities that operated independently of, and sometimes in cooperation with, long-distance networks. On Venetian Crete, trafficking occurred across the ethnic, linguistic, and religious divides between servile, Orthodox, Greek-speaking peasants, who worked large agricultural estates, and the free, Latin, Roman Christian Venetians who owned them. However, as Sally McKee explains, while servile legal status applied to native Greek-speaking Cretans, the enslaved legal status applied only to those individuals who had been trafficked onto the island by merchants and had then been sold to residents of the Venetian colony, or had been purchased by other merchants for further transport to markets across the Mediterranean.63 As in the Adriatic, regional traffickers competed successfully with long-distance traffickers during the thirteenth and much of the fourteenth centuries. For although the Venetians controlled Caffa between 1204 and 1261, and Tana until 1332, the majority of traff icking victims into Crete did not come from the Eurasian steppes, but they were instead collected from raids and kidnappings in southwest Anatolia, main-land Greece, and the other Aegean islands, whose populations consisted largely of Greek-speaking Christians. It was not until the second half of the fourteenth century that Greek-speaking Christians were replaced as slaves by peoples from Eastern Europe and from the Black, Azov, and Caspian Sea regions.64 Despite the losses of Caffa and Tana to the Genoese, the markets of Venetian Crete appear to have become closely connected with both long-distance Genoese and Venetian traffickers over the latter half of the fourteenth century, as the ethnic and national identities of their victims suggest: Mongols, Russians, Circassians, Turks, and Bulgars.

Yet as regional trafficking networks in the Eastern Mediterranean fused with Italian long-distance networks, Black Sea regional operations continued to operate independently, buoyed by new investments from the Byzantine aristocracy. With the ongoing Ottoman conquests, the Byzantine aristocracy began to take an active role in regional trafficking around the Black Sea and the Eastern Mediterranean as they lost their lands to Ottoman expansion. Annika Stello has shown through her studies of the Genoese registries of Caffa between 1410 and 1446 that roughly a quarter of Greek slavers had acquired a wealthy Byzantine patron over the course of the first half of the fifteenth century.65

The Religious Divide

Over the course of the twelfth century, the ongoing papal reform movements and the continuing growth of popular piety increasingly prioritized religious identity over local and ethnic identities and also instilled a sense of community among the faithful. With the consolidation of spiritual authority under the Papacy and continuing military conflict with the Muslims in the Levant and in Iberia, European prelates cultivated a conception of ‘Christendom’ as the territory of Christians as opposed to the lands of Muslims. A side effect of ecclesiastical and popular attention to both religious identity and religious communion was unease towards enslaving coreligionists, because the sense of spiritual community represented in the idea of Christendom triggered social taboos against the enslavement of group members. To be sure, this unease was not novel. The Church in Hippo had rescued members of its congregation from the Galatians in the fifth century, and numerous saints and rulers such as Patrick, Balthild, Charlemagne, and Wulfstan all had either expressed outrage at the sale of fellow Christians or had attempted to curtail their sale by edicts or browbeatings between the sixth and eleventh centuries. It was only by the end of the twelfth century, however, that taboos against enslaving members of one’s own community of faith had passed beyond noteworthy ecclesiastics and rulers and into society at large.

Late twelfth- and early thirteenth-century trafficking patterns are symptomatic of these widespread, long-term social and religious trends. Before the twelfth century, traff icking networks adhered to no bounds of identity. Simply put, traff ickers sold anyone to anyone. As the twelfth century progressed however, the religious divide slowly became the primary social boundary (tenuous although it was) between enslavable and unenslavable groups. For example, Christian and pagan identity in the Baltic generally defined legitimate targets for trafficking and enslavement in border raids and skirmishes. At the same time the religious boundary between Christian and Muslim generally defined legitimately enslavable communities during the Reconquista, and Christian women were sold among Muslims and Muslim women among Christians.

This trend only continued and by the fourteenth century Christian boys in the Balkans were enslaved among the Ottomans and converted to Islam during their time as Janissaries, while Byzantine Christians preyed upon Turkish Muslim communities in the Eastern Mediterranean. In 1296, the Byzantine general Alexios Philanthropenos (1270–1340) enslaved many Turkish women and children after his conquest of the Turks in the Meander Delta. In the early fourteenth century, the Greek historian Nikephorus Gregoras (c. 1292–1360) claimed in his Byzantina Historia that the Byzantines did not enslave their Orthodox opponents, but instead merely took their possessions, a sentiment echoed by the fourteenth-century former Byzantine Emperor Iohannes Kantakouzenos (r. 1347–1354), who wrote in his Historiarum Libri that ‘The Romans [Byzantines] do not enslave men since this is not allowed for them. The only exception is if these are barbarians who do not believe in the care of the savior Christ for us,’ underscoring the dehumanization of ‘the other’ inherent in the process of enslavement. Even as late as 1453, the Byzantine military was raiding and enslaving Turkish inhabitants on the Thracian coastline and then transporting the victims back to Constantinople for sale in the markets.66

These twin senses of religious and community identity would continue to influence the course of human trafficking in the thirteenth century and beyond, but they did not suddenly strike human traffickers with pious guilt about enslaving their coreligionists; again, taboos are not ironclad. For example, in 1288 the Genoese concluded a treaty with the peoples neighboring Caffa, which contained a provision that prohibited the sale of native Orthodox Christians to Muslims. Moreover, all captains of Genoese galleys were then expressly forbidden from transporting enslaved Christians into Muslim lands;67 however, the sale of those Orthodox Christians in Latin Christian lands, such as Venetian Crete or northern Italy, was never addressed.68

Furthermore, the definition of ‘Christian’ itself was carefully crafted and refined so as to delineate ‘true believers’ from political and religious rivals, who then became members of outside enslavable groups. We have already seen how, in the aftermath of Roger de Flor’s assassination in 1305, the Catalan companies adopted the banner of Saint Peter to signal that Greek Christian populations were now henceforth considered schismatics and therefore vulnerable to enslavement. In 1349, Serbian King Stefan Dušan (r. 1331–1355) prohibited the sale of Christians to heretics and infidels under pain of mutilation. The slaver’s hands were to be severed and his tongue cut out.69 However, under Dušan’s law code, to be ‘Christian’ was to be Orthodox, and to be ‘a slaver’ was to be a Latin Christian from the Adriatic coast (i.e. a Venetian). On Crete, as we have seen, the line between free and servile was drawn between Latin Roman Christians and everyone else, including Greek-speaking Orthodox peoples. According to the Venetian notary Manoli Bresciano, 30 percent of slaves sold on the island were Orthodox, even at the end of the fourteenth century, down from 75 percent only three decades earlier in the 1360s.70 Moreover, because ‘Christian’ was so narrowly defined, enslavement itself became a means of encouraging conversion from one Christian rite to another. For example, in Sicily, Frederick III (r. 1295–1337) in 1310 decreed that any Orthodox slave who converted to the Latin rite was to be manumitted no later than seven years after their conversion, and owners were prohibited from then selling the newly converted slaves to lands beyond Sicily against the slave’s will.71

Further still, religious affinity did not create perfect ‘no-slaving zones.’ In 1317, Pope John XXII (r. 1316–1334) blasted the Genoese, arguing that they were strengthening the Muslims by supplying them with Christian slaves. A century later, in 1425, the sale of coreligionists into slavery was still so widespread that Pope Martin V (r. 1417–1431) threatened with excommunication any Christian who persisted in trafficking their fellow Christians into slavery among unbelievers.72 Martin’s successor, Pope Eugenius IV (r. 1431–1447) continued to pressure the Genoese to cease the sale of Christians into Muslims lands. The Commune responded in a letter to Eugenius in 1434 to explain that Genoese law required the Bishop of Caffa to personally inspect every merchant ship carrying human cargo, and to question each slave about their lands of origin and their faith. Any slave who professed the Christian faith or a desire for baptism was to disembark prior to the ship’s departure, but they were not then freed. They were simply returned to the slaver and sold to a Christian buyer.73 Thus while a growing sense of communal identity and religious solidarity served to identify those groups who remained vulnerable to enslavement, the boundaries among different religious groups remained porous, and the enslavement of coreligionists continued to be tolerated in some areas so long as the enslaved remained within the community of faith.

The Pivot: From Slave Trading to Sex Trafficking

It seems that for much of Europe, the broad patterns of trafficking in the high medieval period had little changed. Networks adapted to changing socioeconomic circumstances: intensifying and expanding whenever possible and receding and contracting whenever necessary. With such apparent continuity, how then does the high medieval period represent a pivot? A pivot is a change in the direction of continuous patterns of behavior as opposed to a clean break from earlier patterns, and it is for this reason that I have chosen to argue for a pivot in human trafficking activities from slave trading to sex trafficking over the course of the High Middle Ages. This pivot involved changes in the identities of abductees and in labor expectations that were significant enough, in my opinion, to permanently alter (but not break) patterns of human trafficking activities in Western Europe north of the Alps and Pyrenees. For example, as agricultural slavery declined in Western Europe, male slaves and abductees became less profitable, and the overwhelming majority of trafficking victims were thereafter women and girls.74 Furthermore, for women, enslavement had once meant not only sex work but also labor in traditionally female industries such as domestic care and child rearing, textile care, and food service and hospitality. Sexual appeal and the potential for sexual service added to a female slave’s price, but such services were in addition to taxing and menial slave labor.75 However, as human trafficking pivoted from slaving to sex trafficking, abduction came to mean laboring primarily, if not solely, in sex work, even if that primary labor oftentimes took place under the pretext of domestic service, hospitality, or textile care. Finally, as human trafficking patterns pivoted from slave trading to sex trafficking, the legal status of trafficking victims shifted as well from legally enslaved individuals to legally unenslaved individuals, which also meant the possibility, if not the likelihood, of legal remedy for sex trafficking abductees. Traffickers therefore took greater care to hide their activities from public view. We must remember that these thirteenth-century changes, while profound, mostly affected trafficking patterns in a relatively small geographic area of Western Europe (i.e. north of the Alps and Pyrenees).

Numerous factors came together to revitalize the European urban environment during the twelfth century. Greater security, strong population growth, greater and more reliable food production, and increased trade conducted in permanent urban markets and facilitated by greater access to coin, all led to further urban growth throughout the twelfth century that would continue into the thirteenth century and beyond. It is true that most of Europe was still rural and agricultural, but the medieval town was now a place that could sustain commerce year-round and thus attract people through its gates from its hinterlands and the wider world. As the resident populations of towns grew, buoyed by a constant stream of immigrants from the surrounding countryside, and as foreign merchants became a fixture of medieval town life, commercial sex developed into an industry that catered to the increasing permanent urban population. As the medieval commercial sex industry grew, to meet its labor needs it increasingly turned to human traffickers, who shifted from supplying agricultural labor to supplying sex labor. Yet the commercial sex industry could never fully replace agriculture as a source of demand for human labor, and so trafficking networks in Western Europe during the late Middle Ages would never again match the scale and scope of trafficking activities of previous centuries. Nevertheless, the new source of demand for labor meant that trafficking would continue in Western Europe even as agricultural slavery faded over the late Middle Ages, and in order to understand this pivot, as well as sex trafficking in general, we must first understand the industry that was the source of the demand.

I do not argue that brothels and prostitution were unknown before the twelfth century. Brothels appear to have commonly operated along the major routes to Rome in the eighth century, according to Boniface in his letter to Cuthbert of Canterbury in 747. In the early 820s, Lothar I of Italy decreed that a nun who had left her religious life and had taken up prostitution was to be barred from the gynaeceum, ‘lest that she, who before had intercourse with one man, now have a place for having intercourse with many.’76 David Herlihy observes that the early medieval Latin word for a female textile laborer, gynaecaria, is also a synonym for ‘prostitute,’ and he argues furthermore that if the gynaecea did not double as brothels, nonetheless the women and girls who staffed such workshops were often widely considered to be sexually available.77 Whorehouses feature in The Fall and Conversion of Mary and The Conversion of the Harlot Thais, two tenth-century plays of Hrotswitha of Gandersheim (c. 935–1002), a German canoness, poet, and playwright who lived at Gandersheim Abbey in Lower Saxony.78 Rural areas also certainly had women who, willingly or otherwise, engaged in prostitution as their financial situations changed, as the decrees of Liutprand in the 730s demonstrate. Inns along travel routes certainly had tapsters and servers willing to exchange sexual acts for coin, but these last instances are not what we might consider brothels. Brothels require several components to operate. They need a steady clientele, meaning population centers. They require steady payment in coin, meaning a monetary economy,79 and they require a labor force whose main, if not sole, occupation is sex. These three components came together and began expanding in Western Europe north of the Alps in the late twelfth century.

There were three types of brothel generally found in Western Europe between the thirteenth and sixteenth centuries. Houses of Assignation were domicile arrangements in which the prostitute did not reside in or own the building and paid the landlord a percentage of her fee per client.80 These were probably the earliest type of brothel because they were the most flexible. Potentially any enclosed shelter could become a house of assignation, and because the prostitute did not have to own the property and could rent a room by the client, there was little to no startup cost.

Informal brothels were legally the default establishments of the thirteenth century, since no brothel was officially sanctioned until 1285 in Montpellier. Their existence was precarious, dictated by the whims of civil magistrates and municipal governments, territorial lords, and ecclesiastical officials. Because toleration was the best they could expect, informal brothels were not permanent fixtures in either time or space. They came and went as opportunities arose, and as the demand for sex intersected with the supply of sex labor and of coin. Taverns and inns are perhaps the most famous of these informal brothels, but not every tavern operated as a brothel. Those establishments that did operate as brothels might do so on occasion in order to bring in extra revenue, and then abandon the sex industry when able or pressured by municipal and ecclesiastical authorities to do so. Moreover, homeowners might rent their houses or single rooms to prostitutes as a way of making extra income. In these circumstances, the distinction between a house of assignation and an informal brothel is difficult to draw, and I suggest that the main difference is whether the prostitute worked at the place on a long-term basis (brothel), or simply rented by the client on an ad hoc basis (house of assignation). Having prostitutes living and working onsite meant having a steadier labor supply for the informal brothel-keeper, as opposed to having freelance prostitutes renting rooms as needed, but also it meant that the establishment was more likely to attract unwanted attention from authorities.

Formal, licit, and municipal brothels were institutionalized establishments with permission to operate by official license. They were permanent features of the urban landscape and employed women whose main, if not sole, occupation was sex work. In some cases, these establishments were private enterprises that operated with official recognition and sanction, in other cases, the municipality outright owned and managed the establishment, and in still other cases, the municipality leased the rights to manage and thus prof it from the brothel to private third parties. These institutions began to appear in Europe after 1285 and became popular after 1350 or so. With the development of licensing, houses of assignation and informal brothels became illicit institutions, yet remained a part of the sex industry’s structural landscape.

Before the thirteenth century, evidence for the commercial sex industry is thin. It will become apparent that throughout the twelfth century, and for most of the thirteenth, most of the documentary evidence pertains to France. England has none, as Ruth Mazo Karras has observed; the Dyvers Ordinaunces and Constitutions regulating the ‘orrible synne’ of thebaths, or ‘stewes,’ on the south bank of the Thames, just outside of medieval London, claims in its preamble that the House of Commons under Henry II had enacted its regulations in 1162, but J.B. Post notes that the institution of Parliament did not even exist in 1162. Karras suspects that the London municipal regulations that prohibited ferrymen from transporting men and women across the Thames to the stews after nightfall might date back to the thirteenth century, but she readily concedes that it is impossible to tell for certain.81 While records improve in France during the thirteenth century, in England it is only in the late thirteenth century that the sex industry comes to historical light. As Suzanne Wemple notes, for much of the Middle Ages, prostitution was simply unimportant and generally went unnoted.82

The few passing references to French brothels and prostitutes in the twelfth century confirm that commercial sex was certainly present then, but they tell us almost nothing about its structures during this time. William of Malmesbury, for example, relates that William IX, Duke of Aquitaine (r. 1086–1127), founded a brothel (prostibulum) near the castle of Niort and consorted with a young prostitute (meretricula), but historians debate whether this episode represents a public commercial brothel or a private harem, or perhaps an invective meant to impugn William’s character and reputation.83 We have another reference to brothels in a summa of the first nine books of Justinian’s Code, known as Lo Codi, written in southern France in the latter half of the twelfth century, in which its author declared the marriage of a senator and the daughter of a brothel-keeper invalid, but we do not know if ‘brothel’ indicates a private home, an inn or tavern, or if ‘brothel-keeper’ simply refers to an individual who facilitated vice in general.84

In France, commercial sex had become visible enough by the early thirteenth century that municipal authorities began to reckon with issue. On 31 August 1201, for example, the ‘good men’ (probi homines) of Toulouse, represented by a certain Bernard Raymond, brought a complaint before the municipal authorities of the town regarding prostitutes (meretrices publice) living on the rue de Comminges and in the surrounding area, who were disturbing the residents of the neighborhood day and night. The residents requested that the authorities remove the women and in the future bar them from the street, in accordance with existing (constitutio) statutes that barred prostitutes from living within the city walls. The authorities granted their request and ruled that the women were to vacate the town proper.85 The wording suggests that the city had passed statutes to regulate commercial sex earlier in the twelfth century, but the original ordinances have been lost. As another example, in 1205 the municipal authorities of Carcassonne decreed in article 105, ‘Public prostitutes are to be driven out of the walls of Carcassonne.’86

These legal actions and statutes conf irm that prostitution was certainly active in southern French towns at the beginning of the thirteenth century, but they tell us little else. We know from Mr. Raymond’s complaint that prostitutes were living and working on the rue de Comminges, but this does not indicate if the women were working the streets as freelancers and accompanying clients back to their homes or rooms, or if the women rented rooms in houses of assignation on an ad hoc basis, or if the women worked in informal brothels in which they lived, relatively rooted in time and space. Because Mr. Raymond’s complaint notes that the women were disturbing neighbors both day and night, we might conclude that the women were working in informal brothels on the rue de Comminges, but prostitutes were known to call into the streets in order to advertise their presence, so we do not know whether they were merely loitering in the streets and alerting passersby of their services, or if they were working in establishments located physically on the street.87

Over the course of the thirteenth century, commercial sex had developed structurally to the point that those structures began to be formally addressed in municipal statutes, and we can now properly speak of a growing commercial sex industry. In the early 1240s, houses of assignation and informal brothels come to light in Avignon, when the city banned gambling after curfew in ‘brothels’ and ‘in the homes of prostitutes’ as well as in taverns, inns, and gambling houses.88 Unlike the ambiguous reference to ‘brothel-owners’ in the twelfth-century Lo Codi, Avignon’s thirteenth-century ordinance clearly places brothels and houses of assignation among other recognized public establishments. In 1254, Louis IX (r. 1226–1270) issued his Great Ordinance, which was intended to provide administrative and moral reforms including bans on blasphemy, gambling, usury, and prostitution. The royal proclamation decreed,

Public prostitutes are to be expelled from the fields as well as from the towns, and once these warnings or prohibitions are made, their goods are to be seized by the judges of the locales, or taken, by their authority, by anyone else, to the shirt and robe. Whoever knowingly rents a house to a public prostitute, we wish that house to fall to the lord, by whom it is to be held in feudal commission.89

The Great Ordinance contained instructions that were already being practiced in towns across France, in some cases for decades prior to its proclamation, with the major exception that now prostitutes were not to be tolerated even beyond city walls or outside reputable neighborhoods. Instead, they were to be driven out of the environs of cities entirely. Of greater importance for our purposes is the last sentence that directed local authorities to seize the houses of property owners who knowingly rented their homes to prostitutes, confirming that both houses of assignation and informal brothels were operating now across urban France and not just in a few major southern French towns; in other words, the medieval sex industry was rapidly organizing and spreading. By simultaneously targeting both informal brothels and houses of assignation in towns throughout the kingdom with royal confiscation, this provision not only punished those who profited from the women’s labor, but also aimed to make the expulsion of prostitutes easier by depriving them of physical shelter and social support.

The Great Ordinance of 1254 was followed two years later by a second royal decree in 1256. The intervening two years had apparently taught Louis the futility of trying to extirpate prostitution at the local level. Now prostitutes were only to be expelled from the heart of towns and put outside the walls, but royal interest in undermining the urban sex industry remained steadfast. The 1256 ordinance continued the penalty of property confiscation of any who rented houses or rooms to prostitutes; moreover, in this ordinance Louis officially acknowledged for the first time the existence of brothels by name in his instructions to royal officers to avoid brothels and taverns (de bordeaux et de tavernes).90

The rulings and statutes of Toulouse, Carcassonne, and Avignon, as well as the failure of the Great Ordinance and its subsequent revision in 1256, indicate that municipal authorities across Western Europe were struggling to contain the growth of the commercial sex industry over the course of the thirteenth century. Municipal authorities could regulate the industry by limiting its geographical extent, but they could not extinguish it. They thus tolerated the industry and defined it in the negative; ordinances delineated where prostitution could not take place but did not define where it could. As a result, the industry grew within the sizable gaps of thirteenth-century regulations, and wherever authorities were lax in enforcing them. By the end of the century, towns and cities would begin to define prostitution in the positive, designating areas of communities where such activity could take place, thereby legitimizing and protecting the industry through legal recognition and sanction.

The year 1285 would prove a watershed in the history of the commercial sex industry when, for the first time, sanctioned red-light districts were established in medieval Western Europe. Montpellier, under the authority of James II of Majorca (r. 1276–1311), was granted the right to create a zone wherein prostitution would be legally authorized. In other words, the commercial sex industry had gained the right to exist. The lord bailiff (dominus baiulus), the representative of the Crown in Montpellier, decreed:

the said women [prostitutes] should reside permanently in the remote street commonly called ‘Hot Street’ […]. [The bailiff also promised] to John de Lunello, the advocate appointed by the court, standing for Guirauda of Beziers and Elys of Le Puy present in court, and to each and every prostitute living or wishing to live in this town, that the said women […] will now and forever remain under the protection of the lord king and the council of this town.91

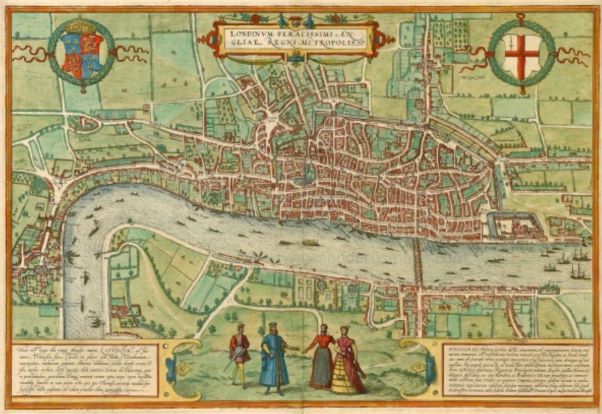

Soon after the establishment of the Montpellier red-light district, Paris itself followed suit. By the 1290s, the capital had designated eight streets where ‘common ribaulds’ could operate legally.92 On the left bank of the Seine, a major area of prostitution grew up around the Bouclerie on the outskirts of the parishes of Saint-André-des-Arts and Saint-Séverin.93 The second major area of prostitution was in the rue Fromental in the university district, which was extremely popular with students.94 In the center of the city, the Île de la Cité, there was a single street allotted for prostitution, known as Glatigny, which became synonymous with vice in medieval Paris. A euphemism for ‘prostitute’ was ‘a girl of Glatigny’ or fillette de Glatigny, while the street itself acquired the suggestive sobriquet val d’amour. Glatigny was in the poor parish of Saint-Landry located close to the port, and the poverty of the area and its proximity to the docks ensured that prostitution remained highly visible in the area for centuries, until royal efforts by Francis I (r. 1515–1547) in the sixteenth century closed the brothels and drove the industry underground.95 The other f ive loci of prostitution in Paris were found on the right bank of the Seine. The rue Champ-Flory was situated outside the walls of Paris proper until the sixteenth century. Therue Chapon was also outside the walls of Paris and was originally located in a modest suburb of the city. Within the vicinity of this street resided the Bishop of Chalons, and this proximity was used as a pretext to ban property rentals to prostitutes on the rue Chapon starting in 1369. Even though the area gentrified, and the brothels became surrounded by more respectable establishments, the ban was never actually enforced, and the rue Chapon retained its reputation for prostitution well into the fifteenth century.96