How two medieval artists illustrated the text’s protagonist a figure assigned female at birth who lived as a eunuch.

By Vanessa Wright

PhD Candidate

Institute for Medieval Studies

University of Leeds

Introduction

This essay analyses the visual representations of the Vie de sainte Eufrosine in three fourteenth-century Parisian manuscripts. It questions how two medieval artists, the Maubeuge Master and the Fauvel Master, approached illustrating the text’s protagonist St Eufrosine/Esmarade, a figure assigned female at birth who lives most of their life as a eunuch in a monastic community. This chapter examines the artists’ depiction of St Eufrosine/Esmarade in three manuscript miniatures, comparing how the artists used signif iers of gender and identity in their portrayals of the saint and other figures to reveal the extent to which the artists represented the saint’s queer gender visually.

The Vie de sainte Eufrosine is a thirteenth-century French verse hagiography of the saint whose preferred name was Esmarade. Composed around 1200, this Life introduces an individual whose gender identity does not conform to a binary model. Esmarade’s queer gender is inextricably linked to their devotion to God as they leave secular society for a monastery in which they spend the rest of their life living as a eunuch. In their accompanying illuminations, the manuscripts of this Life of fer hitherto relatively unexamined visual representations of the saint and their gender expression. This essay considers Esmarade as a genderqueer saint, since they express an identity that does not fit into a binary understanding of gender. Unlike other similar texts, Esmarade does not make an explicit statement outlining their identified gender, and the gendered language used by both protagonist and narrator is inconsistent.1 However, the saint does present themself to others as a eunuch. This could be seen as a way for them to articulate a non-binary, genderqueer identity. Consequently, this essay uses they/them pronouns and the saint’s preferred name, Esmarade, to recognize the saint’s expression(s) of gender.

The Life of Eufrosine/Esmarade tells the story of a saint assigned female at birth who does not wish to marry the partner chosen by their father, preferring to retain their virginity.2 After a brief stay at a monastery with their father Pasnutius, they realize they wish to enter the religious life. Esmarade seeks the guidance of several monks, who each advise the saint to reject marriage for God; one monk cuts their hair and gives them a nun’s habit so that they can join a convent.3 At this point, the monk names the saint Esmarade, an Old French gender-neutral name meaning ‘Emerald’, signalling their move from secular society to the religious life. Esmarade becomes concerned that if they join a convent, their father will be able to f ind them and force them into marriage. Esmarade therefore decides to enter a monastery presenting as a eunuch. Many of the monks are greatly affected by the saint’s beauty, to the point that they request that Esmarade be removed, leading the abbot to place Esmarade in seclusion.4 The saint’s father comes to the monastery, distressed about the loss of his child, and the abbot recommends that the saint counsel him. This continues, without Pasnutius recognizing his child, for many years until Esmarade’s death at the end of the narrative. Moments before death, the saint informs Pasnutius that they are his child, and asks that he alone prepare the body for burial and that he should ensure that no one else sees them posthumously.5 Although the saint does not explicitly state why they wish this, it seems likely that it is to avoid their body being viewed by the monastic community, preventing them from ‘discovering’ Esmarade’s assigned gender. Esmarade’s request, however, is not followed: their body is prepared by another monk and, as a consequence, they are venerated as female both by their fellow monks and by the narrator.6 After death, the saint performs a miracle by restoring a monk’s sight.

The religious and gendered aspects of Esmarade’s identity intersect: the saint’s queer gender is explicitly linked to their religious identity. The connection is first introduced when the monk gives Esmarade the tonsure and a nun’s habit. At this point, the text tells the reader that the saint has been given a new name: the monk ‘changed [their] name; he called [them] Emerald. | This name is common to males and females’.7 These lines inform the reader that the name Esmarade, which the saint retains for the rest of their life, is not associated with a binary gender. This name is given as soon as the saint leaves secular society for a life devoted to God. Emma Campbell suggests that the saint’s spiritual marriage to God, which is marked by their name change, removes them from secular kinship and gender systems.8 As a consequence, the saint is no longer limited by secular understandings of gender and is able to articulate a queer gender that is closely connected with their religious identity.

The saint’s queer gender identity is further highlighted when, on introducing themself at the monastery, they state that they are a eunuch. Eunuchs were a notable part of late Roman and Byzantine society, and also existed in other global contexts, often holding secular positions of power as well as monastic and ecclesiastical roles.9 Eunuchs were assigned male at birth, but if castration occurred before the onset of puberty the development of secondary sexual characteristics would be affected. For example, castration affected skeletal and muscular development and limited the growth of facial and body hair.10 The social gender and gender identity of eunuchs have been the subject of much discussion, with Kathryn M. Ringrose proposing that, in certain social contexts, eunuchs in Byzantium could be considered a third gender.11 Shaun Tougher argues that, although some contemporary sources support Ringrose’s suggestion, later Roman and Byzantine understandings of eunuchs and gender were varied.12 Consequently, we might consider the category of eunuch to constitute a non-binary or genderqueer identity, as the lives of these individuals reveal the limitations of a binary understanding of gender. In fact, in Byzantium, the male pole of the male-female binary was itself a binary, being split between eunuchs and ‘bearded’ (non-eunuch) men.13 On arriving at the monastery, Esmarade presents themself as a eunuch: ‘Porter, let me talk quickly to the abbot! | Say to him that you have left a eunuch at the door’.14 This Life, by showing the AFAB saint declaring themself to be a eunuch, presents a genderqueer individual whose gender disrupts and challenges binary categories.15

The Life has received significant critical attention; scholars have examined Esmarade’s gender expression as well as how the text presents sexuality, family, and other related subjects.16 There has, however, been limited consideration of the visual representation of Esmarade in manuscript illuminations.17 Despite the number of extant manuscript witnesses of Old French hagiographic collections, there is a similar paucity of scholarship concerning the depiction in manuscript miniatures of other saints assigned female at birth who enter the religious life as monks.18 Saisha Grayson, in a study of artistic representations of Sts Marina/Marin, Pelagia/Pelagien, and Eugenia/Eugenius, argues that these saints posed a challenge for medieval artists because they destabilize categories and signifiers, such as clothing, hairstyles, and symbols of status or profession, used to depict identity.19 Grayson states that artists avoided ‘picturing transvestism’, by which she means showing the saint ‘in disguise’ or in transition; however, I argue that presenting the saint as a monk does not obscure this aspect of their Life, but rather privileges their identified gender.20

The Manuscript Context of the ‘Vie de sainte Eufrosine’

The Life is contained in four extant manuscripts, the oldest of these being Oxford, Bodleian Library, Canonici Miscellaneous 74. This codex dates from around 1200 and includes seven saints’ Lives, but unlike the other three manuscripts, Canon. Misc. 74 does not include any accompanying illustrations.21 This chapter therefore examines how artists depicted Esmarade’s queer gender in these other three, closely connected, Parisian manuscripts. This chapter also compares the representation of the saint with other illustrations completed by the same artist within each volume and in other codices, to facilitate a greater understanding of how each artist approached the figure of Esmarade.

The three manuscripts which are the focus of this chapter are: Paris, Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, MS 5204; Brussels, Bibliothèque royale de Belgique, MS 9229-30; and The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, MS71 A 24.22 KB 71 A 24 and BRB 9229-30 share the same contents, but Arsenal 5204 differs in three ways: it does not include the Dit de l’unicorne, found in both BRB 9229-30 and KB 71 A 24, and it contains an additional two items, Les enfances nostre sire Jhesu Crist and the Complainte Nostre Dame.23 These manuscripts were all altered after completion when each had its f irst section, containing the Vie des saints, removed.24

It has been convincingly argued by Richard H. Rouse and Mary A. Rouse that all three manuscripts were produced by Thomas de Maubeuge, a libraire working in Paris in the early to mid-fourteenth century.25 Libraires were lay professionals who coordinated the production of manuscripts, including hiring artists and scribes, but they may have additionally worked as copyists, flourishers, or artists themselves. Although Thomas de Maubeuge would have worked with a large network of scribes, artists, and pen flourishers, there were certain artisans whom he employed frequently. For example, artists like the Maubeuge Master, the Fauvel Master, and the Master of BnF fr. 160 regularly worked for this libraire,as did the scribe Jean de Senlis and the ‘long-nose’ scribe.26

From contemporary documentary evidence, Arsenal 5204 has been provisionally identified as a manuscript purchased in January 1328 by Mahaut, Countess of Artois.27 Thomas de Maubeuge provided a receipt to the Countess at this time recording payment for a manuscript that contained a Vie des Saints and the Miracles de Nostre Dame.28 This identification cannot be conf irmed, however, because Arsenal 5204 does not contain any marks of ownership and the details on the receipt could relate to another codex.29 Although it has been concluded that Thomas de Maubeuge did produce Arsenal 5204, and produced a manuscript very like it for Mahaut, there is no way to prove that these codices are one and the same.30 Arsenal 5204 was copied by Jean de Senlis, and the miniatures were completed by the Maubeuge Master.31

It has been argued that BRB 9229-30, and its detached first volume BRB 9225, were foundation gifts for a Carthusian Charterhouse near Diest, in modern-day Belgium, which was established by Gérard of Diest and Jeanne of Flanders in 1328.32 Although there is no written evidence to link these codices with a specific bookseller, their similarity to KB 71 A 24 and Arsenal 5204 would indicate that they were produced and sold by Thomas de Maubeuge.33 The manuscript was copied by the ‘long-nose’ scribe but there has been some debate regarding the artist(s) who produced this manuscript. Rouse and Rouse identify the artist as the Fauvel Master.34 Rouse and Rouse, with Marie-Thérèse Gousset, compiled a list of fifty-six manuscripts that were illuminated by the artist.35 However, due to the significant differences in the quality of the illuminations, some have concluded that the Fauvel Master’s supposed œuvre is in fact the work of multiple artists.36 Alison Stones states that there were two artists – the Fauvel and the Sub-Fauvel Masters – and that the Sub-Fauvel Master completed a large proportion of the manuscripts usually attributed to the Fauvel Master, often producing work of a lower quality; Stones attributes BRB 9229-30 to the Sub-Fauvel Master.37 However, Rouse and Rouse argue convincingly that the standard of the Fauvel Master’s work could vary within the same codex, and suggest that changes in quality do not always indicate multiple artists but could result from changing practices or constraints.38 It is a matter of continuing scholarly debate whether the corpus of work attributed to the Fauvel Master was completed by one or multiple artists; however, this chapter follows Rouse and Rouse in the understanding that the Fauvel Master was a single artist.

The Fauvel Master’s work also appears in KB 71 A 24, which was owned by King Charles IV of France. As with the other manuscripts, the details of the commission are not entirely clear, but on 30 April 1327, King Charles IV paid Thomas de Maubeuge for a manuscript of saints’ Lives and the Miracles de Nostre Dame.39 In 1373, an inventory confirms that KB 71 A 24 was housed in the French royal library.40 Like Arsenal 5204, KB 71 A 24 was copied by Jean de Senlis, who signed the manuscript on fol. 81v, but the other two hands identified in this codex cannot be assigned to specific scribes.41 As with BRB 9229-30, the Fauvel Master was solely responsible for the manuscript’s programme of illumination.

Representating St Esmarade

Overview

Each of the three versions of the Vie de sainte Eufrosine is accompanied by a single miniature, which appears at the start of the text. These images have several functions: not only do they help the reader to locate texts within the manuscript, but they also present the content of the narrative to the reader. As such these images set up the reader’s expectations of the text, as well as informing their interpretation of the saint, the saint’s behaviour, and the didactic purpose of the Life. An examination of these images quickly reveals that there was no standard way of portraying Esmarade.

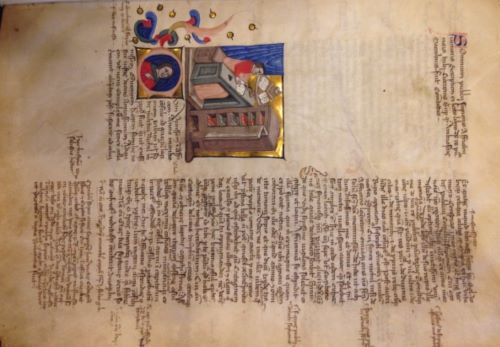

The Maubeuge Master

On folio 87v of Arsenal 5204, the miniature immediately follows the rubric: ‘Here begins [the Life] of St Euphrosyne who was a monk’.42 This rubric, which also appears in BRB 9229-30 and KB 71 A 24, foregrounds Esmarade’s monastic identity to the reader and signals the saint’s gender non-conformance through the juxtaposition of their given name and the grammatically feminine ‘sainte’ with the masculine status of ‘monk’.43 The miniature does not depict a specific episode, but rather focuses the viewer’s attention on the saint themself. Esmarade is presented against a gold background, standing to the left of a white building (Fig. 6.1).This building, based on its architectural style and the content of the Life, represents the monastery in which Esmarade lived. The saint wears a black monastic habit but is not tonsured. The figure faces to the right as if looking upon the monastery. Their left hand is open and gestures towards the monastery whilst the right holds a red book, which, alongside their clothing and position in the frame, serves as a visual signifier of the saint’s monastic identity.

By presenting Esmarade without a tonsure, the Maubeuge Master marks them as different from the other religious and clerical figures found in this codex. Although this miniature does not include any other figures with whom we could compare the saint, the manuscript features many representations of monks, priests, and clerics, who are all shown in typical garb befitting their role. The rubrics that accompany these miniatures often identify the social role of the individual, but the images themselves also differentiate social groups by dress and other signifiers. Monks, priests, and clerics are all presented tonsured and wearing long monastic habits in mostly neutral colours. There is variety in how the hair of these figures is depicted. Clerics and priests are mostly presented with longer, curling hair to the jawline whereas, in the majority of cases, monks are depicted with a band of short hair above the ears, with no curls – but all are tonsured. Robert Mills notes that the tonsure was considered a sign of access to God as it was a visual signifier of clerical status.44 Therefore, despite the rubric that states that Esmarade ‘fu moinnes’ (‘was a monk’), the Maubeuge Master has explicitly differentiated the saint from cisgender male religious or clerical figures through the artist’s choice of hair style or head covering.

Instead of a tonsure, the artist depicts Esmarade with what either could be shoulder-length hair or a head covering. Although the lines of paint could suggest strands of hair, a close examination of the miniatures in this manuscript reveals that, whilst cisgender male figures are often shown with longer hair, or with short hair curling back from the forehead, no one is shown with long, uncovered hair in the style shown in this miniature. It is therefore more likely that the artist decided to present Esmarade with their hair covered, and it is important to consider how this affects the representation of the saint.45 Having compared the miniature to the seven portrayals of nuns and abbesses in this codex, it is clear that the artist has not chosen to represent Esmarade as a female religious, as the veils worn by nuns are different in shape, style and colour.46 There are many instances of laywomen wearing headdresses; most wear their hair up, covered by a green headdress, but there are examples of individuals who wear a green headdress along with a white head covering. However, it is the Virgin Mary’s head covering which most closely resembles that worn by Esmarade. The Virgin Mary is one of the most frequently depicted figures in this manuscript and her appearance is generally consistent throughout: she wears a long orange robe with a blue cloak, and her hair is covered by a white head covering – the folds of the fabric being clearly visible – and a crown.47 By presenting Esmarade in a similar head covering, the artist associates them visually with the Virgin Mary but also with St Thais, whose Life immediately precedes that of Esmarade.48

Thais’ Life (fols. 78r-87v) is illustrated by three miniatures, in which Thais, similarly to the Virgin Mary, wears a blue gown and orange cloak, with a white head covering. In aligning Esmarade with these saintly figures, the Maubeuge Master highlights the saint’s holiness, but by presenting Esmarade using the visual signifier of the head covering, the saint is associated with their assigned gender.In using iconography related to the Virgin Mary and St Thais, as well as monastic and clerical figures, the Maubeuge Master renders visible the rubric’s juxtaposition of ‘sainte’ (‘[female] saint’) and ‘moinnes’ (‘monk’). Although this illumination includes a feminine signifier, this does not mean that assigned gender is foregrounded and the saint’s queer gender is obscured entirely from view. Instead, it is through combining the typically feminine and masculine signifiers of the head covering and monastic dress that the artist is able to signal that the saint’s identified gender is outside of the gender binary.

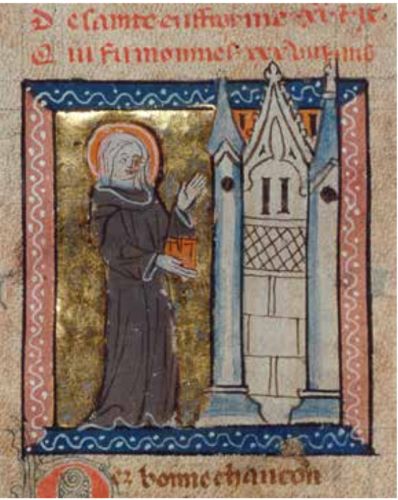

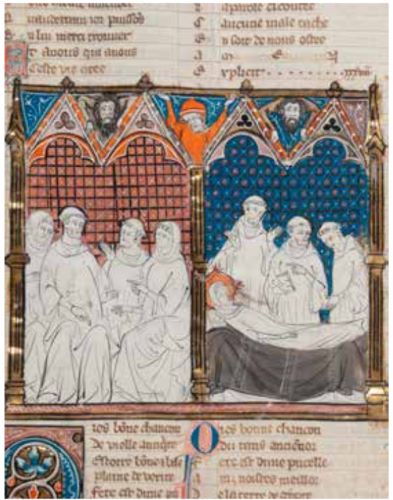

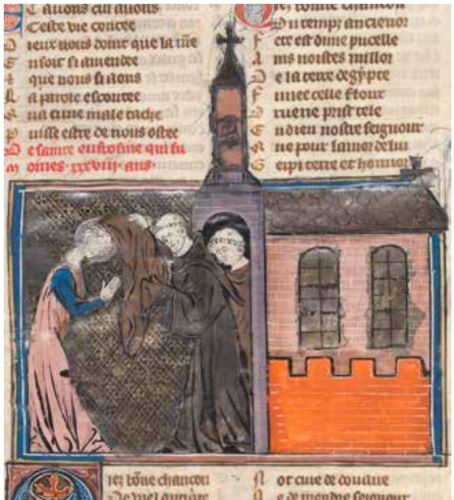

The Fauvel Master

The Fauvel Master completed two miniatures of Esmarade, in BRB 9229-30 (Fig. 6.2) and KB 71 A 24 (Fig. 6.3). These images present different episodes from the narrative. There are similarities in the artist’s approach to these miniatures, and in the programmes of illumination in the manuscripts more generally; for example, the Fauvel Master makes frequent use of architectural motifs in these images and others. The most important similarity between the representations of Esmarade is that each image depicts the saint’s relationship with their fellow monks. Rather than depicting the saint as a solitary figure, as occurs in Arsenal 5204, the Fauvel Master portrays Esmarade as part of a monastic community.

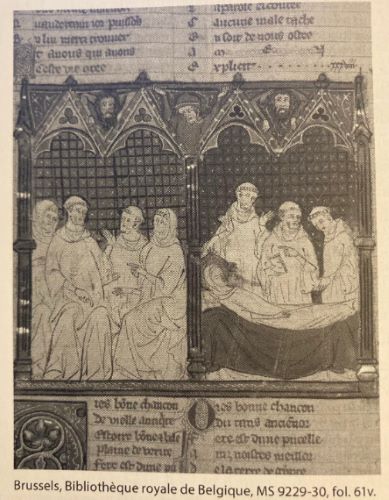

In BRB 9229-30, the miniature that accompanies the Life of Esmarade is composed of two registers showing different scenes from the narrative (Fig. 6.2). The left-hand register illustrates a group of four monks. The second figure from the left (possibly representing the abbot) and the monk on the right, who represents Esmarade, sit in the foreground and are positioned facing towards each other. This placement and their hand gestures indicate that they are in conversation. This does not accurately ref lect the narrative as Esmarade, after entering the monastery, is almost immediately placed in seclusion, but this scene functions to highlight the saint’s integration into the monastic life and identity. All four are tonsured and wear monastic dress, with the monks on the extreme left and right having their heads covered. The only visual difference between them is that three of the four monks are bearded. The beardless figure, who sits on the right, has some slight damage to the lower half of their face: the line of the nose is smeared and there is a small mark where the mouth should be, but the figure’s jawline and beardlessness have not been obscured. It is unlikely that this erasure was intentional or caused by readers because the damage appears to have occurred before the paint had fully dried.49 A lack of facial hair, which was a common visual signifier of eunuch identity, is used by the Fauvel Master here to distinguish the saint from the other monks, and it also serves to highlight their genderqueer identity.50 Although one could argue that the lack of facial hair was used by the artist to present the saint as female, an examination of the right register of this miniature suggests that this is not the case. In the right register, the saint is depicted with long hair without the tonsure which serves, as will be discussed later, to illustrate the monks’ discovery of the saint’s assigned sex.51 Considering that the Fauvel Master uses hair to portray the saint’s assigned gender in the right register, it seems unlikely that they would not use hair to the same representative end within the same illumination. Consequently, as Esmarade is depicted with the monastic tonsure and beardless, we can understand this lack of facial hair to depict the saint as a eunuch.

The right-hand register shows the saint’s death scene: Esmarade’s body is laid out on a bed, behind which stand three monks. Although the saint is in the foreground, greater emphasis is placed on the monks and their reactions to the saint, which are revealed through their gestures.52 The monk to the right gestures towards the saint’s body, and the monk to the left-hand side holds his hands up, palms open, in a gesture of surprise. The gestures of the monk in the centre are noteworthy as, although he looks towards the right-hand monk, he points to the left: not towards the saint’s dead body, but to the left-hand register and the figure of Esmarade. This links the two registers together and indicates to the viewer that the supine figure shown is that of the beardless monk from the other scene. Another significant element of this miniature is the additional figures painted into the architectural framework above the two registers. These three bearded figures gaze down at the scene, with the figure in the centre appearing to hold up the miniature’s frame with both hands. These onlookers are both internal and external to the image, and their positioning and facial expressions serve to direct the reader’s attention. The left and central figures look towards the left register as if watching the discussion between Esmarade and their fellow monks. Consequently, they emphasize this aspect of the miniature and the saint’s life to the reader. The right-hand figure plays a slightly different role as they look out of the image at the reader: in doing so, their direct gaze challenges the viewer to interpret and respond to the scene displayed below.

Although the saint remains fully clothed after death, there is a change to their physical appearance. Whilst they appear with a tonsure in the left register, in the right register their hair, although covered, is longer and sweeps to either side from a central parting. Ogden argues that the representation of the saint in each register portrays the monks’ perspective; the artist illustrates how the monastic community perceives Esmarade’s gender at different points in the narrative.53 The addition of longer hair therefore demonstrates that, after learning of the saint’s assigned sex, they view the saint as a woman. However, we could equally argue that the artist makes these changes to reflect the understanding of the narrator: the narrator also returns to identifying Esmarade as female by using the saint’s given name as well as grammatically feminine agreements, pronouns, and other markers.54

In considering the change in hairstyle between the two registers, it is worth comparing this depiction of Esmarade to other illuminations by the same artist. The Fauvel Master portrays Esmarade with the longer hairstyle again in their representation of Esmarade in KB 71 A 24 (Fig. 6.3): the saint wears secular clothing associated with their assigned gender and has long, loose hair that falls from a centre parting. This hairstyle is also found elsewhere in KB 71 A 24: the Virgin Mary is presented with a similar hairstyle, for example, on fol. 13v. When illuminating a manuscript of the Legenda aurea (Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek München, MS CLM 10177), the Fauvel Master presents the Life of St Pelagia/Pelagien in a similar way to Esmarade in BRB 9229-30 (Fig. 6.4).55 Both of these scenes are set out in similar ways, with, in Figure 4, the saint, whose preferred name was Pelagien, being shown on their deathbed surrounded by monastic figures but significantly they are portrayed with long, uncovered hair.56 From an analysis of hairstyles used in this manuscript, and others, it is clear that the Fauvel Master frequently used this hairstyle to represent individuals assigned female at birth. Consequently, in using this hairstyle for Esmarade and Pelagien, the artist privileges assigned over identified gender.

In each register of the miniature of Esmarade in BRB 9229-30, the Fauvel Master offers a different depiction of the saint. In both images, their monastic identity is stressed not only by their dress, but also through their interactions with the monastic community. Their position as a eunuch is reflected in the left-hand register, but this genderqueer expression is not found in the right-hand register, in which the saint’s assigned gender is presented instead. In this way, the image accurately reflects as well as reinforces the narrative as Esmarade’s genderqueer identity is shown during their life in the monastery, before being eventually obscured after death. After this point, the saint’s gender identity is reinscribed by their father and monastic community, their genderqueer identity is ignored, and they are celebrated as female. This therefore leads to the erasure, or at least minimization, of the saint’s non-normative gender identity and expression.

The miniature of Esmarade in KB 71 A 24 offers a different perspective from those previously discussed. Over half of the miniature is taken up by the monastery and the pair of monks who stand in its doorway (Fig. 6.3). The two monastic figures are shown tonsured and wearing black/brown habits. One of the monks remains in the doorway whilst the other steps out towards the saint, who is depicted on the left. Esmarade stands with their head inclined and hands together in prayer as the first monk dresses them in a habit. The saint’s move from a secular to religious identity is marked by the exchange of a light pink robe with dark blue sleeves for a habit. This pink and blue robe appears in thirteen other miniatures in this manuscript.57 In each of these cases it is worn by cisgender laywomen, both married and unmarried, which thus emphasizes both Esmarade’s move from a secular to a religious identity, and a change in their gender expression.58 As discussed earlier, the saint’s hair is worn long and loose.

It is possible that the miniature in KB 71 A 24 illustrates not the saint’s entry into the monastery, but rather their earlier decision to join a convent. At this point in the narrative, a monk advises Esmarade to avoid marriage, and to dedicate their life to God instead. The monk addresses the question of lay clothing directly, stating: ‘“It is necessary for you to change your secular clothing”’.59 It is arranged for someone to come and help the saint cut their hair, and to provide clothing suitable for a nun. The clothing scene is described as follows: ‘The clothing was prepared, the shears were brought; | [They] had themself tonsured and clothed in the manner of a nun’.60 The narrative stresses the monk’s involvement in this process, commenting that he tonsured and blessed the saint. The miniature could therefore ref lect this scene, especially considering the monk’s active role in dressing the saint. However, a similar scene takes place when Esmarade joins the monastery: the abbot gives the saint the tonsure and dresses them in their monastic habit. It is possible that this is a conflation of the two scenes but, given the space taken up in the miniature by the monastery building, it seems more likely that this image was intended to represent the later scene.61 If this is the case, it is important to note that the illustration does not accurately ref lect the events of the narrative, in which Esmarade changes from their nun’s habit to clothing typical of a nobleman, and approaches the monastery presenting as a eunuch. Ogden argues that, by not showing Esmarade putting on secular male dress, this scene minimizes the saint’s queer gender and focuses instead on them being given monastic dress by a religious authority.62 Although the Fauvel Master does not depict the saint as a noble eunuch, they do present Esmarade in the process of transition. By illustrating the saint putting on monastic clothing, the artist foregrounds the moment when, on entering the monastery, Esmerade is able to fully articulate their queer gender and religious identity. However, by portraying the saint using clothing and visual signifiers associated with their assigned gender, the artist obscures Esmerade’s identification as a eunuch; consequently, this miniature does not fully represent their gender identity. This image has significance in a wider context because it is one of the few examples in which the process of transition is represented visually, with most manuscript illuminations presenting the saint either in their assigned gender or after transition.63

There has been some damage to the saint’s face meaning that we can no longer see their facial features and expression. The rest of the miniature, including the monks’ faces, remains intact, which indicates that one or more readers paid specific attention to this portrayal of Esmarade. Unlike in the miniature from BRB 9229-30, this damage occurred after the illustration was complete. However, it is not clear whether the damage is the result of intentional erasure, or the result of readers touching the saint’s face, which, over time, would have removed the paint. Kathryn Rudy suggests that kissing and touching of manuscripts and images were part of individual devotional practices and provides many examples of such behaviour and its effects.64 No other miniatures in this codex display this kind of erasure, suggesting that at least one of the readers had a strong response, be it one of acceptance, rejection, or another type of reaction, to this Life or this representation. The reader’s intervention is likely to have affected, and will continue to affect, later readers in their reading and understanding of the saint. The erasure may have drawn later reader’s attention to the miniature and the figure of the saint specifically, causing them to spend more time examining and interpreting the image as well comparing its portrayal to the narrative.

It is relevant to consider why the Fauvel Master represented different scenes in these two versions of Esmarade’s Life. We should remember that artists would produce large numbers of illuminations, and it is unlikely that they would be able to recreate images at a later date without using templates or having an exemplar to follow.65 Another factor that might affect representation was the type of instruction provided. Artists would not necessarily have a detailed knowledge of the texts; rather, they generally worked from instructions or the rubrics to create interpretations. Rouse and Rouse note that some instructions to artists have survived in these manuscripts, generally written in plummet in the lower margins.66 Such notes are often difficult to read as they have been partially erased or worn over time, but can be seen on fols. 197r and 152r of Arsenal 5204; fols. 127r and 158r of KB 71 A 24; and on fols. 5r and 32v of BRB 9229-30.67 It is not generally possible to identify the hand in which such notes are written; it could be that of the artist, the libraire or other people involved in the codex’s production. If these instructions were given by the libraire, it is possible that they reflect the interests of or requests from the commissioner. The libraire may have had the commissioners in mind and adapted any instructions accordingly. BRB 9229-30 was first owned by a group of Carthusians whereas KB 71 A 24 was owned by Charles IV of France. This may explain why the illumination in BRB 9229-30 focuses on the saint as part of a monastic community; however, this remains speculation as no marginal instructions related to Esmarade’s Life are visible in any of the three manuscripts.

Conclusion

To conclude, our extensive knowledge surrounding the production of Arsenal 5204, BRB 9229-30, and KB 71 A 24, and the artists who worked on them, provides a rare opportunity to analyse representations of a single figure across multiple codices. The Maubeuge and Fauvel Masters illuminated a significant number of manuscripts, meaning that it is possible to compare iconographic details across their work to uncover patterns of representation. Their depictions of Esmarade, although different in style, size, and design, share some significant features. Most importantly, each miniature highlights the saint’s religious identity and the important role of the monastery in their Life. The images completed by the Fauvel Master in particular emphasize the saint’s engagement with the monastic community and integration into the religious life. Although their religious identity is highlighted by each artist, Esmarade’s queer gender expression and eunuch identity are illustrated less consistently. Nevertheless, their non-normative gender is at no point entirely ignored or obscured from view. The visual signifiers of gender and social position chosen by the Maubeuge and Fauvel Masters, and the combinations in which they are used, reveal how these artists approached expressions of gender that challenged binary understandings and categories. Whereas much scholarship has been centred on literary portrayals of genderqueer and transgender saints, attention to manuscript illumination and production provides valuable additional insight into understandings and representations of non-normative gender, genderqueer identities, and their expression in late medieval culture.

Appendix

Endnotes

- See, for example, Life of Margaret-Pelagia/Pelagien (Jacobus de Voragine, La Légende dorée, pp. 966-68).

- Hill, Vie, pp. 191-223. All quotations of the Old French text are from this edition. Translations are the author’s own. Any personal pronouns referring to Esmarade that are not supplied in the Old French will be translated as singular they/them and placed in square brackets.

- Cutting or shaving hair was a part of the ritual of becoming a nun, showing their entry into the religious life (Milliken, Ambiguous Locks, p. 37.).

- The narration explicitly states that the monks desire Esmarade as a eunuch; see Hill, Vie, pp. 205-206, ll. 566-78. This is important to note as some previous scholarship has interpreted the monks as being attracted to the saint’s femininity. See, for example: Anson, ‘Female Transvestite’, p. 17.

- Although Esmarade uses their given name and feminine gendered vocabulary when explaining matters to their father, I do not consider this a ‘return’ to their assigned gender, but rather it has a distinct purpose as it is used to show familial connection. The use of gendered vocabulary is different at the Life’s conclusion as the narrator and other characters use it to reinscribe Esmarade into their assigned, binary gender.

- It is notable that, after death, Esmarade tends to be referred to as ‘le cors’ (‘the body’) rather than by name. ‘Le cors’ is used seven times in ll. 1130-259 (Hill, Vie, pp. 219-23), which run from the saint’s death to the end of the Life (excluding the narrator’s concluding address).

- ‘Se nom li at cangié; Esmarade l’apele. | Cis nons est commuaz a marle et a femele’ (Hill, Vie, p. 202, ll. 445-46).

- Medieval Saints’ Lives, pp. 99-100.

- Tougher, Eunuch, pp. 8-11.

- Ringrose, ‘Shadows’, p. 91.

- Ibid., pp. 85-109; Tougher, Eunuch, pp. 109-11.

- Tougher, Eunuch, p. 111.

- See Szabo in this volume: pp. 109-29.

- ‘Portier, fai moi parler vias a dant abé! | Dis li que a la porte as laissiét un castré’ (Hill, Vie, p. 204, ll. 514-15).

- Amy V. Ogden argues that the saint, in these lines and in other conversations with the abbot (Hill, Vie, p. 204, ll. 524-25), uses ambiguous phrasing and does not declare the eunuch identity explicitly. Ogden suggests that this allows them to express their queer gender without having to lie about their assigned sex (Hagiography, pp. 84-85). However, this chapter argues that by introducing themself to the monastery as a eunuch, whether indirectly or not, the saint establishes their genderqueer identity. For Ogden’s latest research on this Life, including a reassessment of her earlier arguments, see pp. 201-21 in this volume. See also ‘AFAB’ in the Appendix: p. 286.

- See, for example, Gaunt, ‘Straight Minds’; Hotchkiss, Clothes, pp. 13-31; Ogden, Hagiography; Campbell, Gift, pp. 99-100 and ‘Translating Gender’.

- Ogden (Hagiography, pp. 48-51) provides detailed description and analysis of the text’s manuscripts and their illuminations, and Emma Campbell also includes an examination of the manuscript miniatures in her 2019 article ‘Translating Gender’ (pp. 240-44); this chapter will offer interpretations of these manuscript miniatures focusing on their representation of a genderqueer saint.

- This group of saints includes Eufrosine/Esmarade, Marina/Marin, Pelagia/Pelagien, Margaret-Pelagia/Pelagien, Theodora/Theodore, and Eugenia/Eugenius. Old French versions of these lives can be found in Clugnet, ‘Vie’, pp. 288-300; Jacobus de Voragine, La Légende dorée. Martha Easton (‘Transforming’, pp. 333-47) and Saisha Grayson (‘Disruptive Disguises’, pp. 138-74) discuss the visual representation of these and other saints. For a discussion of saintly ‘transvestism’, and a critique of the latter term, see: Bychowski in this volume, 245-65, especially 245-53.

- Grayson, ‘Disruptive Disguises’, pp. 139-40. Grayson conflates the saints Pelagia/Pelagien and Margaret-Pelagia/Pelagien, but these are two distinct saints and there are significant differences between their Lives.

- Grayson, ‘Disruptive Disguises’, p. 144.

- Ogden, Hagiography, p. 24.

- These manuscripts will be referred to as Arsenal 5204, BRB 9229-30, and KB 71 A 24. Arsenal 5204 is fully digitized, and KB 71 A 24 is partially digitized with only the manuscript miniatures available online.

- At the time of completion, BRB 9229-30 and KB 71 A 24 contained La Vie des saints, Gautier de Coinci’s Miracles de Nostre Dame, La Vie des pères, LeDit de l’unicorne, LaVie de sainte Thais, La Vie de sainte Eufrosine, Les Quinze signes du jugement dernier, and Huon le Roi de Cambrai’s Li regres Nostre Dame. Arsenal 5204 contains in addition to the above Les enfances nostre sire Jhesu Crist and the Complainte Nostre Dame but lacks the Dit de l’unicorne. (Van den Gheyn, Catalogue, pp. 338-44; Rouse and Rouse, Manuscripts, i, 189-91.)

- In at least two cases, these removed sections were rebound as separate codices. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS fonds français 183 was originally bound with KB 71 A 24, and Bibliothèque royale de Belgique, MS 9225 with BRB 9229-30, but unfortunately the Vie des saints text from Arsenal 5204 has been lost (Rouse and Rouse, Manuscripts, i, 18 9 – 9 0).

- Rouse and Rouse argue that at least two of these manuscripts were sold by Thomas de Maubeuge and, considering their similar size, date, and contents, it is likely that he produced all three (Rouse and Rouse, Manuscripts, i, 189). For more information on Thomas de Maubeuge and his customers, see: ibid., 173-83.

- For information on the scribes and artists who worked for Thomas de Maubeuge, see: ibid., ii, 182-86.

- Ibid., i, 189.

- Ibid.

- The records of this purchase from Mahaut’s household do not match Arsenal 5204 exactly: the records state that the manuscript included an Apocalypse. No such text is found in the manuscript, though this might be a reference to the Quinze signes du jugement dernier, which does figure in its contents. The record reads ‘A mestre Thomas de Malbeuge libraire pour .i. Roumant contenant la vie des sains, lez miraclez Notre Dame, la vie des sains perres, et L’Apocaliste et pluisers autres hystoires […].’ (‘To monsieur Thomas de Malbeuge, libraire,for a book containing the Vie des saints, the Miracles de Nostre Dame, the Vie des pères, and the Apocalypse and many other stories’). Rouse and Rouse, Manuscripts, ii, 175.

- Ibid., I, 197.

- Ibid., ii, 184.

- Ibid., i, 195; Hogg, ‘Carthusian General Chapter’, p. 367.

- Rouse and Rouse, Manuscripts, i, 194.

- Ibid., ii, 184; Stones, ‘Stylistic Context’, p. 529. This artist was named after Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS fonds français 146, which contains the Roman de Fauvel.

- Rouse and Rouse, Manuscripts, ii, 195-200.

- Ibid., i, 208.

- Stones, ‘Stylistic Context’, pp. 530-32, p. 558. Stones refers to the Master of BnF fr. 160 as the Master of BnF fr. 1453, but these are two designations for a single artist (Morrison and Hedeman, Imagining the Past, p. 144).

- Rouse and Rouse, Manuscripts, i, 210.

- Ibid., i, 188.

- Delisle, Recherches, ii, 148; Rouse and Rouse, Manuscripts, i, 194.

- Jean le Senlis copied quires 10 to 24 of KB 71 A 24 (Rouse and Rouse, Manuscripts, ii, 183).

- ‘Ci endroit coumence | De sainte euphrosyne | Qui fu moinnes’ (fol. 87v).

- The rubric in BRB 9229-30 is found in the lower margin of fol. 61v whereas the Life starts around halfway down the first column after the miniature. In KB 71 A 24, the rubric is found in the first of the three columns of text, immediately before the miniature; the text itself begins after the miniature.

- Mills, ‘Tonsure’, pp. 111-13. Mills notes that although nuns were also required to cut their hair on entering a convent, their heads were then covered by the veil.

- This is also supported by Campbell’s analysis of the image: ‘Translating Gender’, p. 240.

- These figures are found on fols. 48v, 54r, 56r, 72v, 124r, 140v, and 170r.

- The Virgin Mary is represented in 42 of 161 miniatures contained in this manuscript.

- St Thais’ Life recounts that Thais was a rich, beautiful woman who, with the help of a hermit, rejected her past life and sins. After burning her clothing and possessions, she was imprisoned in penance and prayer.

- Similar damage is found in the right-hand register, depicting the saint after death where the black outline of the pillow and the facial features of the monk standing to the right are also smeared.

- Tougher, Eunuch, pp. 112-14.

- Long, loose hair was typically associated with women, and had multiple symbolic meanings: it could be interpreted as a symbol of beauty, virginity, and youth, but also of unrestrained sexuality (Milliken, Ambiguous Locks, pp. 171-77). See Easton, ‘Transforming’ for more on representations on hair and gender in hagiography.

- Ogden, Hagiography, p. 51.

- Ibid., p. 49.

- For example, in the narrator’s concluding address, Hill, Vie, ll. 1260-79 (p. 223).

- Bu sby, Codex, i, 33; ii, 716. The Life states that the AFAB saint was converted to Christianity after leading a luxurious, worldly life. The saint refused the devil’s attempts to tempt them and decided to leave Antioch to live as a (male) hermit; they gained renown under the name Pelagien. After their death, a visiting priest discovered the saint’s assigned sex while preparing the body for burial. (Jacobus de Voragine, La Légende dorée, pp. 963-66.)

- The Fauvel Master appears to have painted many scenes in this way, which suggests that they had a template for representing deathbed scenes as similar images; for example, a miniature on fol. 42v of KB 71 A 24 shows a monk lying on a bed being cured by the Virgin Mary, with four other monks standing behind their bed. Although this monk is presented as ill, rather than dead, the resemblance between the three images is evident.

- On fols. 43v, 53r, 61v, 79r, 88v, 93v, 112v, 121r, 127r, 160r, 168r, 176r, and 180r.

- The Virgin Mary is shown wearing this robe on fol. 43v, which is different from her usual attire in this codex. Given the relative consistency with which she is depicted elsewhere in the codex, I do not consider this garment to be typical of the Virgin Mary.

- ‘Ton abit seculer toi covient a cangier’ (Hill, Vie, p. 199, l. 329).

- ‘Les dras ot aprestez, les forces fait venir; | A guise de nonain se fait tondre et vestir’ (ibid., p. 202, ll. 437-38).

- Campbell also suggests that the habit Esmarade is given by the monks may be a conf lation of the nun’s and monk’s habits that the saint receives in the text (‘Translating Gender’, p. 240).

- Ogden, Hagiography, p. 50.

- Another example is discussed by Mills (Seeing Sodomy, pp. 200-208), Grayson (‘Disruptive Disguises’, pp. 144; 155-65), and Ambrose (‘Two Cases’, pp. 8-11): a sculpture of St Eugenia/Eugenius at a monastic church in Vézelay in which the saint, in monastic dress, is presented at the moment at which they are required to bear their breasts to prove their innocence of rape. Mills (Seeing Sodomy, p. 204) interprets this sculpture as reflecting a moment of transition.

- Rudy, ‘Kissing Images’.

- Rouse and Rouse, Manuscripts, i, 201.

- Ibid., i, 200.

- Ibid.

Bibliography

- Ambrose, Kirk, ‘Two Cases of Female Cross-Undressing in Medieval Art and Literature’, Source: Notes in the History of Art, 23.3 (2004), 7-14.

- Anson, John, ‘The Female Transvestite in Early Monasticism: The Origin and Development of a Motif ’, Viator, 5 (1975), 1-35.

- Busby, Keith, Codex and Context, 2 vols. (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2002).

- Campbell, Emma, Medieval Saints’ Lives: The Gift, Kinship and Community in Old French Hagiography (Cambridge: Brewer, 2008).

- —, ‘Translating Gender in Thirteenth-Century French Cross-Dressing Narratives: La Vie de Sainte Euphrosine and Le Roman de Silence’, Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies, 49.2 (2019), 233-64.

- Clugnet, Léon, ed., ‘Vie de Sainte Marine’, Revue de L’Orient Chrétien, 8 (1903), 288-300.

- Delisle, Léopold, Recherches sur la libraire de Charles V, 2 vols. (Paris: Champion, 19 0 7), ii.

- Easton, Martha, ‘“Why Can’t a Woman Be More like a Man?” Transforming and Transcending Gender in the Lives of Female Saints’, in The Four Modes of Seeing: Approaches to Medieval Imagery in Honor of Madeline Harrison Caviness, ed. by Evelyn Staudinger Lane, Elizabeth Carson Pastan, and Ellen M. Shortell (Farnham: Ashgate, 2009), pp. 333-47.

- Gaunt, Simon, ‘Straight Minds/“Queer” Wishes in Old French Hagiography: La Vie de Sainte Euphrosine’, GLQ, 1.4 (1995), 439-57.

- van den Gheyn, J., Catalogue des manuscripts de la Bibliothèque royale de belgique, 10 vols. (Brussels: Henri Lamertin, 1905), v.

- Grayson, Saisha, ‘Disruptive Disguises: The Problem of Transvestite Saints for Medieval Art, Identity, and Identification’, Medieval Feminist Forum, 45 (2 0 0 9), 138 – 74.

- Hill, Raymond T., ed., ‘La Vie de Sainte Euphrosine’, The Romantic Review, 10.3 (1919), 191-223.

- Hogg, James, ‘The Carthusian General Chapter and the Charterhouse of Diest’, Studia Cartusiana, 1 (2012), 345-70.

- Hotchkiss, Valerie, Clothes Make the Man: Female Cross-Dressing in Medieval Europe (New York: Garland, 1996).

- Jacobus de Voragine, La Légende dorée, ed. by Jean Batallier and Brenda Dunn-Lardeau, trans. by Jean de Vignay (Paris: Champion, 1997).

- Milliken, Roberta, Ambiguous Locks: An Iconology of Hair in Medieval Art and Literature (Jefferson: McFarland, 2012).

- Mills, Robert, Seeing Sodomy in the Middle Ages (Chicago: University of Chicago, 2 015).

- —, ‘The Signification of the Tonsure’, in Holiness and Masculinity in the Middle Ages, ed. by P. H. Cullum and Katherine J. Lewis (Cardiff: University of Wales, 2005), pp. 109-26.

- Morrison, Elizabeth, and Anne D. Hedeman, Imagining the Past in France: History in Manuscript Painting, 1250-1500 (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2010).

- Ogden, Amy V., Hagiography, Romance, and the Vie de Sainte Eufrosine (Princeton: Edward C. Armstrong, 2003).

- Ringrose, Kathryn M., ‘Living in the Shadows: Eunuchs and Gender in Byzantium’, in Third Sex, Third Gender: Beyond Sexual Dimorphism in Culture and History, ed. by Gilbert H. Herdt (New York: Zone, 1996), pp. 85-109.

- Rouse, Richard H., and Mary A. Rouse, Manuscripts and Their Makers: Commercial Book Producers in Medieval Paris, 1200-1500, 2 vols. (Turnhout: Miller, 2000).Rudy, Kathryn M., ‘Kissing Images, Unfurling Rolls, Measuring Wounds, Sewing Badges and Carrying Talismans: Considering Some Harley Manuscripts through the Physical Rituals They Reveal’, The Electronic British Library Journal, 2011 <http://www.bl.uk/eblj/2011articles/articles.html> [accessed 25 February 2017].

- Stones, Alison, ‘The Stylistic Context of the Roman de Fauvel, with a Note on Fauvain’, in Fauvel Studies: Allegory, Chronicle, Music, and Image in Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, MS Français 146, ed. by Margaret Bent and Andrew Wathey (Oxford: Clarendon, 1997), pp. 529-67.

- Tougher, Shaun, The Eunuch in Byzantine History and Society (New York: Routledge, 2008).

Chapter 6 (155-176) from Trans and Genderqueer Subjects in Medieval Hagiography, edited by Alicia Spencer-Hall and Blake Gutt (Amsterdam University Press, 04.06.2021), published by OAPEN under the terms of an Open Access license.