Exploring the subject of immigration in U.S. history with particular attention to the two and a half decades from 1890 to the start of World War I.

Originally published by Newberry Digital Collections for the Classroom, 09.05.2017, Newberry Library, republished with permission for educational, non-commercial purposes.

Introduction

Is the United States “a nation of immigrants,” a “land of opportunity,” and refuge for the world’s persecuted and poor? Is the country made stronger by its ability to welcome and absorb people from around the world? Or are the new arrivals a burden? Should the United States close its borders to immigrants because of their numbers, their countries of origin, their politics, religions, financial means, educational levels, or medical conditions—all of which have been factors in one or more immigration laws over the past 150 years? What does it mean to be an immigrant, to be born in one country and spend much of one’s life in another? What consequences does immigration have for the individuals, families, and communities who migrate?

Debates over immigration dominate today’s newspaper headlines and political campaigns. These debates may be new in some of their particular concerns (the border with Mexico, Islamist terrorism), but many of the questions raised and arguments presented would have been deeply familiar to a reader in 1900. Almost since the founding of the republic, Americans and their legislators have weighed the benefits of welcoming new citizens from around the world against the benefits of restricting immigration, monitoring the activities of the foreign born in the United States, and narrowing the path to citizenship. One line of debate has focused on the issue of political influence and, specifically, the fear that foreigners within the United States promoted political radicalism. With the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798, the U.S. Congress and President John Adams sought to limit the influence of the French Revolution by deporting certain immigrants and closing immigrant-owned, opposition presses on the grounds of treason. In the late nineteenth century, immigration laws specifically forbade entry to any suspected anarchists; Communists would be targeted later in the twentieth century.

Another line of debate over immigration has focused on its economic impact. U.S. policy makers have vacillated between accommodating agricultural and industrial employers, who demanded a broad, inexpensive, and often temporary labor pool, and workers, who objected that the influx of immigrant labor created too much competition and drove down wages. Immigration from Latin America, for example, may seem the overriding issue today, but was not restricted at all until 1965, largely because of the demand for Mexican agricultural labor in Southwestern and Western states. The Chinese, in contrast, became the first ethnic group specifically barred from entry to the United States with the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, passed under pressure from white workers’ organizations in the West that resented Chinese competition for jobs in mining and railroad construction.

Finally, debates over immigration often turn on understandings of cultural difference and on changing expectations of how foreign-born people should adapt to and participate in American society. There have always been two primary paths to U.S. citizenship: One is through being born in the United States. The other is through naturalization, the legal process by which individuals apply for and are admitted to citizenship. But beyond this legal process, what are the expectations of citizenship? What is the process of assimilation, or absorption into, American culture? Can immigrants retain the customs or languages of their countries of origin and participate sufficiently in American society or are these practices in conflict? And which groups—government officials, politicians, journalists, “native-born” citizens, or immigrants themselves—should be in a position to decide?

This collection explores the subject of immigration in U.S. history with particular attention to the two and a half decades from 1890 to the start of World War I. As historian Roger Daniels explains in Guarding the Golden Door: American Immigration Policy Since 1882, the late nineteenth century witnessed an enormous increase in the number of arriving immigrants. More immigrants—11.7 million—came to the United States between 1871 and 1901 than had arrived in the United States and the British North American colonies during the preceding three centuries combined. (The U.S. population was 76.2 million in 1900.) Between 1900 and 1914, 12.9 million new immigrants arrived. These turn-of-the-century immigrants came primarily from Southern and Eastern Europe, and were largely Italians, Jews, and Poles.

This period also saw significant changes in the government’s management of immigration. In 1891, the U.S. Congress determined that the issue would fall, exclusively, under national control. Congress removed any power that state commissions had previously held and established a new federal Bureau of Immigration. In 1892, the Bureau opened the Ellis Island immigrant receiving station in New York, through which approximately 70 percent of all immigrants would pass over the coming decades. Federal laws proceeded to restrict immigration over the coming decades, culminating in the passage of the Immigration Act of 1924. This act imposed a national quota system based on the 1890 census. As a result, foreign countries were allotted a specific number of annual entries to the United States in proportion to their presence in the United States in 1890. The act favored nationalities such as English, Irish, and Germans who had arrived before 1890 and severely limited arrivals from Eastern and Southern Europe. No numerical limit was placed on immigration from North or South America. Asians were completely excluded as they remained ineligible for citizenship. Other categories of people were excluded because they were deemed criminals or otherwise immoral, paupers (very poor people), contract laborers, political radicals, illiterates, or physically or mentally unfit. In 1943, Congress repealed the exclusion acts and established quotas for people from Asian countries. But the 1924 law remained largely in effect until the Immigration Act of 1965, which ended the national quotas system.

The documents here approach the history of immigration and citizenship from several different angles: national and personal identity, the experience of immigration, immigrant life in the cities, and political debates over immigration.

Nation of Immigrants

These three documents represent different moments in what is now a long tradition of defining America as a nation of immigrants. Crèvecoeur offers one of the earliest formulations of this idea—and of the metaphor of different races “melted” together—in this passage from Letters from an American Farmer, written at the start of the American Revolution. Crèvecoeur was born in France in 1735 and moved to the British colony of New York at the age of 24, where he bought a large farm and settled down to raise a family seven years before the start of the war.

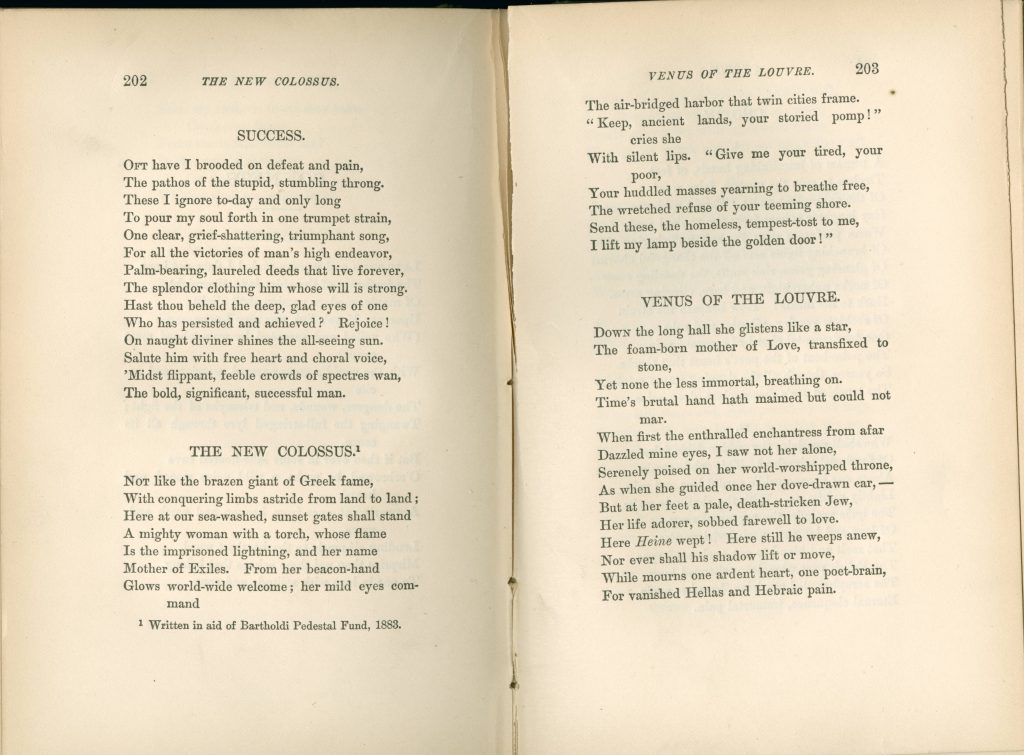

In Letters from an American Farmer, he adopts the persona of James, a Pennsylvania farmer, who writes to a friend in England to explain American ways. (Ironically, Crèvecoeur did not favor American independence from England and lost his family as well as his farm in New York in the violence of the Revolution.) “Uncle Sam’s Thanksgiving Dinner” appeared in the magazine Harper’s Weekly just four years after the close of the Civil War, as many Americans were trying to envision national identity in the wake of such a profound internal rupture. It also responds to early debates around restricting Chinese immigration. The poet Emma Lazarus grew up in New York in a Jewish family of Portuguese descent in the nineteenth century.

After 1879, she became particularly concerned about the persecution of Jews in Russia and Eastern Europe. She wrote this poem in 1883 to help raise money for a pedestal for the Statue of Liberty on Ellis Island. This poem was installed on a bronze plaque inside the statue in 1903, after her death. [Please note: The old colossus mentioned at the start of the poem is the Colossus of Rhodes, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. The twin cities are New York and Brooklyn, not yet consolidated into one entity.]

Immigration Debates in Cartoons

These political cartoons from two popular nineteenth-century magazines both take up the question of whether specific national groups should be excluded from American life. The Harper’s illustration responded to a bill in the New York legislature that proposed to fine and imprison anyone who hired Chinese contract workers. The illustration accompanied a brief column describing the bill and dismissing the alleged threat of a “Chinese invasion” against which American workers must be protected. The columnist concluded that “A majority in this country still adhere to the old Revolutionary doctrine that all men are created free and equal before the law, and possess certain inalienable rights.”

Eighteen years later, the Puckcartoon takes a quite different approach to the controversy concerning Irish immigrants. This cartoon accompanied an editorial that argued that the United States, like European countries, had developed “a national type… This type is strong enough to assimilate to itself all foreign types which fall fairly under its influence.” However, the editorial goes on to criticize supporters of Irish independence from England as “a class of voters who are American only in name, and Irish in feeling and conduct.” Both cartoons personify America as Columbia, a goddess-like embodiment of the nation who appears in art and literature from the eighteenth century forward.

Experiences of Immigrants

These documents represent various experiences that were shared by many immigrants who arrived in the United States between 1890 and 1924: being inspected at Ellis Island, performing or seeking work, getting lost or searching for relatives who have been lost in transit, and attending civics and English language classes.

The photographs appear in Edward Alsworth Ross’ The Old World in the New. Ross, a professor of sociology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, takes a fiercely anti-immigrant stance in his book.

However, these photographs, taken by journalists and reformers, offer a compelling record of immigrant experiences and a counterweight to Ross’ rhetoric, examined later in this collection. Edith Abbott was an economist, social worker, and educator who helped establish the School of Social Service Administration (SSA) at the University of Chicago and served 18 years as its dean.

These documents are selected from a source book that she compiled from government records, scholarly articles, and other sources for the benefit of SSA students.

Neighborhoods and Tenements

The great majority of turn-of-the-century immigrants settled in cities, such as New York and Chicago. The two maps included in this section offer graphic representations of the distribution of immigrants at both local and national levels.

Samuel Sewell Greeley’s Nationalities Map was published by Hull House in 1895 as part of a project to document and describe how people lived and worked in Chicago’s poorest neighborhoods. Hull House was a settlement house established in Chicago’s Near West Side slum as part of a movement to redress the widening gulf between the poor and the affluent in America’s cities.

Middle-class women and men lived at Hull House and provided services, classes, and organizational support to people in the neighborhood. In order to gather information to create this map and others, staff from Hull House and the federal Bureau of Labor went through the neighborhood house by house and asked residents about their ethnic origins, their work and wages, and the number of people in their households.

Edward Alsworth Ross, a sociology professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, saw the urban settlement patterns of immigrants as a problem. He argued that the new arrivals would overwhelm cities’ capacities to provide housing and other services. Ross created this map to illustrate the concentration of new immigrants in cities throughout the United States.

Indeed, the work of Jacob Riis vividly portrays the difficult living conditions that many immigrants faced in New York City. Riis was a Danish immigrant, who experienced severe poverty himself before becoming a celebrated photographer and social reformer advocating on behalf of the urban poor. In How the Other Half Lives, Riis documented conditions in the slums of New York’s Lower East Side—at the time, the most densely populated place on earth. Unlike Ross, who sought to address urban conditions by severely restricting the flow of new immigrants, Riis responded to these conditions by seeking to change them. He initiated a campaign to reform building codes and improve living conditions in the tenements, the dark, crowded, over-priced structures which housed three-quarters of New York’s population.

Nativism

Edward Ross was a sociologist at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in the early twentieth century. He endorsed nativism, or the favoring of native-born inhabitants over immigrants, and advocated severe restrictions on immigration. In the preface to this book, he responds to people who see the welcoming of new immigrants as part of America’s democratic and humanitarian promise by writing, “I am not of those who consider humanity and forget the nation, who pity the living but not the unborn…I regard [America] as a nation whose future may be of unspeakable value to the rest of mankind, provided that the easier conditions of life here be made permanent by high standards of living, institutions and ideals…We could have helped the Chinese a little by letting their surplus millions swarm in upon us a generation ago; but we helped them infinitely more by protecting our standards and having something worth their copying when the time came.” He proceeds to argue that “the original make-up of the American people” was English Puritans, French Protestants, Germans, and Scotch-Irish. He laments that recent immigrants are predominantly Italian, Slavic, and Jewish.

Immigration and Identity

While the readings that open this collection address the issue of national identity, these texts by W. E. B. DuBois and Mary Antin explore questions concerning personal identity. DuBois was a prominent African American intellectual and civil rights advocate who, in The Souls of Black Folk, examined the history of African Americans and their place within American society. DuBois grew up in Massachusetts, relatively sheltered from racism, and earned a PhD at Harvard. But he lived in an America defined by Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), the Supreme Court decision that introduced the doctrine of “separate but equal” and upheld the constitutionality of state laws requiring racial segregation. In this passage, DuBois considers what it means to be both black and American in a discussion that resonates with immigrant writers who wonder what it means to be both American and Irish or Italian or any other ethnicity.

Mary Antin was born into a Jewish family in Polotzk, Russia, in 1881 and moved with her family to Boston when she was 13 years old. Although her father struggled to support the family, Antin received a strong education at the local public schools and grew up to become a celebrated writer and lecturer on the immigrant experience. Her autobiography, The Promised Land, portrays her childhood in Polotzk and Boston, contrasting the persecution and oppression that Jews experienced in Russia to the opportunity and success she found in America.

Selected Sources

- Roger Daniels. Guarding the Golden Door: American Immigration Policy and Immigrants Since 1882. 2004. pp. 27–58.

- Mae M. Ngai. Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America. 2004. pp. 227–264.

- Robert Siegel. Jacob Riis: Shedding Light On NYC’s “Other Half.” www.npr.org/templates/story/

By Dr. Hana Layson

Manager of School and Educator Programs

Portland Art Museum

By Dr. Daniel Greene

Adjunct Professor of History

Northwestern University