Many non-European ethnic groups and nationalities have migrated to Europe over the centuries.

Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Interethnic Relations in Early Modern History (ca. 1500–1800)

By Dr. Benjamin Conrad

Teaching and Study Coordination

Institut für Geschichtswissenschaften

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin

By Dr. Tobias P. Graf

Professor of History

Institut für Geschichtswissenschaften

Humboldt Universität zu Berlin

By Arndt Wille

PhD Student in History

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin

Overview

Contrary to nationalist narratives which generally postulated ethnic homogeneity within the boundaries of given nation-states, early modern Europe was ethnically diverse. This is most obvious in the case of territorially extensive polities such as the Habsburg and Ottoman realms, which are commonly referred to as ‘multi-ethnic empires’. However, significant ethnic diversity existed even in much smaller spaces. This makes twentieth- and twenty-first century conceptualisations of nationality as inadequate for understanding early modern ethnic relations as the concept of borders. When people in this period spoke about Germans, for instance, they meant not just the inhabitants of what we might think of today as the ‘German-speaking lands’ (Germany, Austria, and parts of Switzerland), but also populations living in Poland-Lithuania, Silesia, Bohemia, Croatia, Transylvania, and the Baltic. These demographics were not necessarily the result of recent migrations, but had existed for a significant period of time. While a combination of language and descent were important for contemporary understandings of ethnic belonging, other elements such as religion played an equally important role.

In a first step, this chapter discusses early modern conceptions of ethnic difference before investigating ethnic coexistence and conflict in Europe through the example of Poland-Lithuania. It then turns to a discussion of the status and treatment of Jews and the Romani people (often referred to as ‘gypsies’) at the hands of majority populations. The final section explores the place of European indigenous peoples such as the Sámi of Scandinavia.

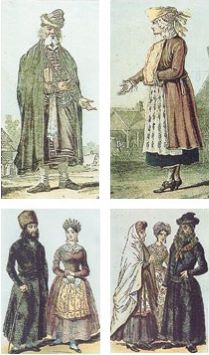

Ethnicity in Early Modern History

From today’s point of view, ethnicity appears to be a ubiquitous category in early modern texts of all genres. Contemporaries clearly distinguished between Germans, Italians, French, Poles, Turks, and so on, and there was considerable fascination with the different languages, customs (including dietary habits), ‘national character’ (reputations for ingenuity, servility, or violence, for example), and styles of dress associated with different ‘peoples’. These interests are amply attested to by ethnographic descriptions included in geographical texts, travel accounts, and missionary reports, as well as numerous manuscripts and printed costume books. Characteristically, such works mixed first-hand observations to varying degrees with information extracted from authoritative ancient and biblical texts. Nevertheless, for most of the early modern period, there was no general theory or widely accepted concept of ethnicity in the modern sense, even as contemporaries freely used ethnonyms and grouped individuals into peoples and nations. These concepts frequently remained ambiguous, combining and conflating ethnic, geographic, linguistic, and religious identifications, while also sometimes providing shorthands for describing juridical subjecthood to a given ruler, such as the King of Spain. Ostensibly ethnic terms such as ‘Turk’ at once designated a Muslim and a subject of the Ottoman Sultan. The phrase ‘to turn Turk’ found in numerous European languages denoted religious conversion to Islam. Perhaps unsurprisingly, ethnonyms frequently served the purpose of constructing the otherness of different communities, especially to exclude perceived aliens such as Jews and Roma (see below).

The term nation, although used relatively frequently in early modern sources, did not imply the same degree of ethnic, linguistic, and political homogeneity associated with it from the late eighteenth century onwards. In administrative terms, a nation was usually a loose grouping of people of similar geographic, linguistic, and religious background. Although the Ottoman Empire, for instance, recognised a French ‘merchant nation’ under the commercial privileges (Ottoman Turkish: ʿahdname-i hümayun) granted to the French king, these rules also governed English merchants until 1580 and thus did not necessarily coincide with political affiliations. As practical arrangements, such privileges regulated the assessment and collection of customs duties and taxes, as well as the resolution of conflict among merchants.

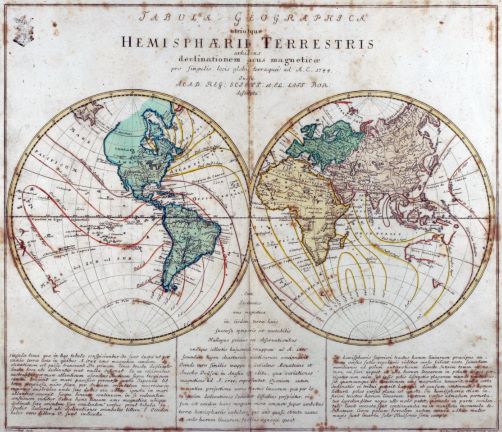

The shift towards a more systematic distinction of ethnic groups occurred only in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries with the formulation of theories of race. Such attempts to establish a ‘scientific’ categorisation of human beings, which built on Carl Linnaeus’s (1707–1778) system of taxonomy, were stimulated by European interactions with the inhabitants of other parts of the world. In the process, the term race—which had previously, and rather vaguely, signified descent from a noble family, or could be used more generally as a synonym for people (especially in English)—acquired its modern meaning of membership in a biologically defined ethnic group, which nevertheless remained culturally and socially constructed. In spite of the scientific ideals of objective classification, proponents of race theory like Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) enshrined ideas of alterity, which could be used to provide justification for colonial rule and slavery. Such theories also encompassed minorities in Europe like the Scandinavian Sámi, whom Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon (1707–1788) judged to have “few virtues, and all the vices of ignorance”. Although very influential, such theories provide no insight into the practical organisation of interethnic relations in Europe.

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth as an Example of an Early Modern Multiethnic Polity

While there is much that is unique about the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the cohabitation of multiple ethnic, linguistic, and religious groups observed here, as well as the institutions and policies adopted in relation to ethnic diversity, in many respects resemble those found in other early modern empires like Russia, Habsburg-ruled Southeast Europe, and the Ottoman Empire. After the Union of Poland and Lithuania in 1569, the Commonwealth was one of the six largest European polities. Although formally an elective monarchy, contemporaries already referred to Poland-Lithuania as the ‘Republic of Poland’ (Rzeczpospolita) because of the great political influence of the wealthiest part of the nobility, the Magnates. The Union brought together a staggering variety of beliefs and languages. Roman and Greek Catholics formed the dominant religious groups but there were also large numbers of Jews, Greek Catholics, and Protestants in the country. Polish and Ruthenian (a relative of today’s Ukrainian and Belarusian languages) were the most important Slavonic languages spoken in the Commonwealth besides Lithuanian. In addition, the population included a considerable number of German and Yiddish speakers.

At the beginning of the early modern period, the population of Poland was estimated to consist of around seventy percent Poles, fifteen percent Ruthenians, and at least ten percent Germans, with the rest comprised of Armenians, Jews, Karaites, Romani, Tatars, Vlachs and others. After the Union with Lithuania, Poles still formed about fifty percent of the overall population, whereas forty percent were Lithuanians and Ruthenians, with the remaining ten percent made up of Germans, Jews, non-Lithuanian Balts, and other ethnicities.

It is worth noting that these groups were differentiated not only by their languages and religions, but also by their professions and their geographic distribution. The diversity of the Polish-Lithuanian population was further increased by the immigration of groups of Dutch, Italians, and Scots, some of which enjoyed limited forms of communal autonomy. In fact, the only group never granted such a status were the Roma, whom the Poles regarded as economically, socially, and politically unimportant. The greatest measure of autonomy was accorded to the Jewish community, which had the right to administer its members across Poland-Lithuania independent of their specific places of residence. Similar arrangements, allowing even for a measure of state-enforceable jurisdiction in internal matters, existed for Christian and Jewish communities in the Ottoman Empire, as well as for expatriates such as merchants officially recognised by the Ottoman sultans. This model was at times applied to settler communities within Europe, such as the Huguenot immigrants to various German states.

Such multi-cultural, multi-lingual, and multi-religious societies were not free from conflict. Throughout the early modern period, Poland-Lithuania witnessed several riots over ethnic and communal differences and, occasionally, minorities were expelled. This happened, for example, to the Protestant Socinian Society, also called the Polish Brethren, during the Polish-Swedish War (1655–1660). The Socinians afterwards took refuge in the Netherlands, the non-Polish part of Prussia, and Transylvania, which provided a safe haven for a number of radical Protestant groups from all over Europe.

The relative political weakness of Poland-Lithuania’s royal government and the limited power of its king in this period is comparable perhaps only to the situation in the Holy Roman Empire. This potentially gave individual groups greater bargaining power here than elsewhere in Europe, but the overall pattern of organisation and cohabitation was by no means unique.

Outsiders Within: Jews and Roma

‘Stateless’ and scattered across numerous countries, Jews and Roma were often referred to as strangers within, troublemakers, or enemies by the dominant societies of early modern Europe. However, a clear ethnic, social, or religious classification was considered difficult: Jews, who formed the largest minority in early modern Europe, were understood as both an ethnic and a religious community. Their position was fraught with a great deal of ambivalence. While Christian majority societies sometimes regarded them as witnesses of faith who were worthy of protection, Jews were also aggressively stigmatised as blasphemers and diabolical evildoers, or even held responsible for the death of Christ. And although customs, rites, laws, and languages (including Yiddish, Judaeo-Italian, Judaeo-Spanish, and Hebrew) ensured a distinct Jewish identity, strict segregation was a concern for Christians (and to some extent, for Jews themselves).

Segregationist measures came to an unprecedented climax with the expulsion of the Sephardic Jews from Spain in 1492: after the conquest of Granada (then the last remaining Islamic kingdom in the Iberian Peninsula), the Spanish monarchs sought to homogenise their ethnically and religiously highly diverse subject populations. Sephardic Jews faced the choice of either baptism or execution if they refused to leave Spain. A similar measure in 1609 targeted Spanish Muslims (called Moriscos) and their descendants, feared to be an Ottoman ‘fifth column’. Both policies triggered massive migratory movements. While most Moriscos went to North Africa, the Jews scattered more widely, moving to Portugal (where they were in turn evicted in 1496/1497), the Ottoman Empire, North Africa, Italy, and some cities in northern Europe. Even those Iberian Jews who opted for conversion so that they were allowed to stay (the so-called conversos) were suspected of ‘crypto-Judaism’ by the Spanish Inquisition. Furthermore, the proto-racist concept of limpieza de sangre (‘purity of blood’) functioned to preserve clear socio-symbolic boundaries between Old and New Christians.

While the expulsion of 1492 was unprecedented in its scale, European Jews had been subjected to regular expulsions across the continent since the Middle Ages. Such measures were later frequently replaced by resettlement policies, enacted by European rulers seeking economic and fiscal benefits from the skills, commerce, and financial networks of Jewish people.

Where the presence of Jews was tolerated, ecclesiastical and secular authorities made frequent attempts from the Middle Ages onwards to visually distinguish Jews from Christians, through distinctive clothing and markings such as the yellow badge. Separate streets and city quarters—notably the Venetian Ghetto established in 1516 and the segregation measures implemented in the Papal States by Pope Paul IV (1476–1559) in 1555—created largely separate spheres of life. Legislation aimed at Jews was passed to regulate everyday interactions with Christians, for example by prohibiting unregulated interreligious disputations and sexual contact. Jews were excluded from membership in the guilds and numerous other fields of employment such as agriculture. Nevertheless, these laws and ordinances also protected Jewish life, in combination with the existing grants of safety of body and property as well as limited rights of communal self-administration. As peddlers, pawnbrokers, cattle dealers, merchants, luxury traders, glaziers, goldsmiths, lenders, and doctors—or as court Jews, Hebrew teachers, and also as friends and lovers—Jews were an essential part of Christian societies in spite of their segregation. The true emancipation of Jews, however, did not occur until the end of the early modern period, during the Enlightenment and the French Revolution, or, in some areas, even later.

Like the Jews, the Roma, who had come to Western Europe at the beginning of the fifteenth century, soon faced considerable mistrust. As pilgrims equipped with papal, imperial, and local safe-conducts, groups of Roma were initially welcomed in most parts of Europe. Yet by the turn of the sixteenth century elites began questioning the narrative of the penitential pilgrims. The Roma were described as ‘strange’ in terms of skin colour, language, and their high mobility (although the latter was often the result of necessity rather than choice). Contradictory ethnic labels such as ‘Egyptians’, ‘Gypsies’ and ‘Tatars’—the Romani word Roma does not appear in early modern sources—as well as frequent (but incorrect) abuse of the Roma as ‘heathens’ all point to the difficulties contemporaries found in placing the ‘new’ minority into any clear category. Over the course of the early modern period, some commentators came to doubt that they were a people in their own right, claiming, among other things, that Romani identity had simply been assumed by vagabonds, thieves, and robbers.

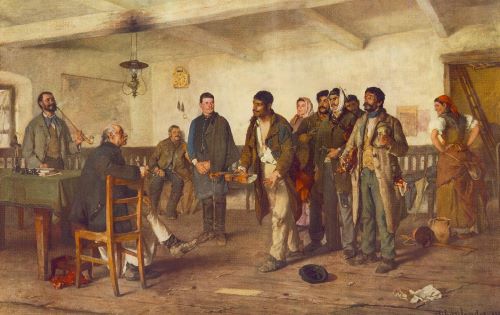

By the sixteenth century, Roma communities increasingly fell victim to marginalisation and discrimination. Stigmatising accusations of laziness, dishonesty, theft, robbery, fraud, espionage, magical practices, and bargaining with the devil made their situation much more difficult. In addition, numerous European territories tried to expel the Roma under the regulations of ‘poor laws’, which were aimed especially at itinerant groups. Despite these hardships, Roma worked as blacksmiths, basket makers, horse traders, construction and farm workers, traders, healers, entertainers, miners, soldiers, and even in law enforcement. They were often highly specialised workers and thus played a complex role in most early modern European societies, meaning that their history cannot be reduced to persecution.

The status and fate of the Roma as a group—or, more precisely, as a wide range of communities—also varied over time and space. While those living in Hungary were at times more firmly integrated into feudal structures and faced less marginalisation, Roma communities were enslaved for several centuries in the principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia. After a period of extensive persecution during the eighteenth century, a few countries launched new disciplinary policies to aggressively integrate and assimilate the Roma. In addition to older Spanish settlement initiatives, the ‘enlightened’ rulers of the Habsburg Empire, Maria Theresa (1717–1780) and Joseph II (1741–1790), enforced a rigid settlement policy (particularly in Burgenland in present-day eastern Austria) which also aimed at undermining Romani collective identity. Unlike in the case of the Jews, the situation of the Roma witnessed few substantial improvements even as the early modern period came to a close.

Europe’s Indigenous Peoples

Ambivalence also characterised the dealings of majority populations with ethnic groups today recognised as indigenous peoples within Europe, such as the Tatars in Poland-Lithuania, the Sorbs in Poland and Germany, or the Sámi in northern Scandinavia. Among these groups, the Sámi deserve particular attention because they formed one of the last remaining European groups of pre-Christian faith. The largely (but not exclusively) nomadic, reindeer-herding Sámi inhabited territories divided between Russia, Denmark-Norway, and Sweden. Especially as suppliers of expensive furs, many Sámi groups were closely integrated into commercial networks in all three polities. Although Christian missions to the Sámi had already been undertaken in the Middle Ages, the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries saw a renewal of state-backed Christianisation efforts by Swedish and Norwegian Protestants as well as Russian Orthodox monks. Intended to stamp out pagan beliefs, missionaries undertook considerable efforts to seek out and destroy traditional religious sites while establishing new churches in Sámi settlements.

Even in the eighteenth century, the Sámi (who were called Laplanders at the time) had a reputation for witchcraft and magic which seems to have been connected to traditional shamanic practices interpreted by the Christian clergy and rulers as devil worship. Although King Christian IV of Denmark and Norway (1577–1648) issued a decree calling for the vigorous persecution of Sámi witchcraft in 1609, the number of Sámi accused of this crime was relatively low, suggesting that, despite their reputation, the Sámi were not particularly vulnerable to allegations of witchcraft.

Both witchcraft persecutions and renewed missionary efforts need to be seen in the context of attempts by Swedish and Danish-Norwegian monarchs to increase control over the Sámi through taxation and trade. Especially in the eighteenth century, the Scandinavian crowns promoted the influx of Finnish and Swedish settlers, with the aim of developing their northern territories agriculturally, while an increasing number of Sámi abandoned their nomadic lifestyle to take up farming and animal husbandry. The same period, however, also witnessed an expansion of Sámi reindeer herding, which continued to require a nomadic lifestyle.

Politically, the Sámi nomads played a key role in the attempts of Denmark-Norway and Sweden to delineate their common borders, since claims to territorial control were linked to usage of the land by the subjects of the respective monarchs. The so-called Lapp Codicil, an addendum to the Strömstad Treaty (concluded in 1751), protected the nomadic lifestyle of Sámi reindeer herders by recognising their right to cross this border in order to access pastures and other key resources, even in times of war. At the same time, however, the requirement that herders fixed their juridical subjecthood, along with the subsequent hardening of the borders between Norway, Sweden, and Russia, increased the pressure on them to assimilate to the majority populations and submit to the authority of the respective states.

Conclusion

People living in the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries were aware of the ethnic diversity of Europe, even if what we today refer to as ethnic categories were more fluid at that time. Ethnicity, ‘peoplehood’, and ‘nation’ did not have the same political significance ascribed to them by nineteenth- and twentieth-century nationalism, and different ethnic groups (defined by geographic origins, language, cultural practices, and religion) coexisted in all European polities. Of course, such coexistence was not necessarily always peaceful, and there were significant power asymmetries between different groups. Especially marginalised minorities such as Jews and the Romani people were generally disadvantaged and abused. On the other hand, their identities as distinct groups—imposed from the outside by European majority populations as much as they were constructed from the inside by members of such communities—did at times afford them a degree of protection and autonomy, especially when early modern authorities considered it expedient. This model of relative communal autonomy with direct relations to the ruler was characteristic not only of Poland-Lithuania but also most other multi-ethnic polities. To some extent, this principle also extended to Europe’s indigenous peoples such as the Sámi. However, the right of self-administration also existed in tension with rulers’ attempts to increase their control over their subjects, mobilise their resources, and homogenise their beliefs. In this sense, therefore, interethnic relations in early modern Europe were precarious, unstable, and subject to change over time. They remained volatile after 1800 when nationalist and racist ideologies took early modern scientific theories of race to the extreme, in order to justify exploitation, colonisation, violence, and even extermination in Europe and overseas. Long before that, Europe’s deepening entanglements with lands and peoples beyond its shores had already given rise to a growing presence of people from distant countries—the result of conquest, enslavement, and religious missions. In the sixteenth century, for instance, Sevilla was home to a sizeable community of people of African descent. Thus Europe’s ethnic diversity further increased in the early modern period.

Interethnic Relations in Modern History (ca. 1800–1900)

By Dr. Jarsolav Ira

Research Coordinator, Comparative Modern History

Institute of World History

Charles University

By Dr. Erika Szívós

Associate Professor of History

International Commission for the History of Towns

By Dr. Irina Marin

Professor of Political History

Utrecht University

Overview

Ethnicity or ethnic group, as with similar collective nouns, is a commonly used but fuzzy concept. Most dictionary definitions stress that ethnicity presupposes a group of people that share a number of communal identity features, the most frequently invoked being language, culture, traditions, rituals, sometimes religion, and a sense of common descent. While to this day theorists of ethnicity debate its nature and its composition, in nineteenth-century Europe the concept itself did not exist, and only came into usage in the twentieth century. The concepts that circulated at the time varied greatly across time and geographical space. Depending on author and historical context, the demographic map of Europe was inhabited by peoples, nations, nationalities, or races. These concepts were sometimes used interchangeably; in other contexts, they designated very specific historical realities. In some cases, they were mere ethnographic terms; in others, they acquired political meaning.

Ethnic groups had, of course, existed before the nineteenth century and were mentioned by travellers, chroniclers, historians and governmental officials. What the nineteenth century introduced was a sharpening (and sometimes artificial creation) of lines of demarcation between various ethnic groups across Europe, and their reconceptualisation as ‘nations’, which came to be regarded as the legitimate basis for states. The emergent disciplines of folklore collection, ethnography, philology, and statistics processed group differences and came up with distinct categories of peoples. Thus, they also served as instruments of codification, regularisation and unification.

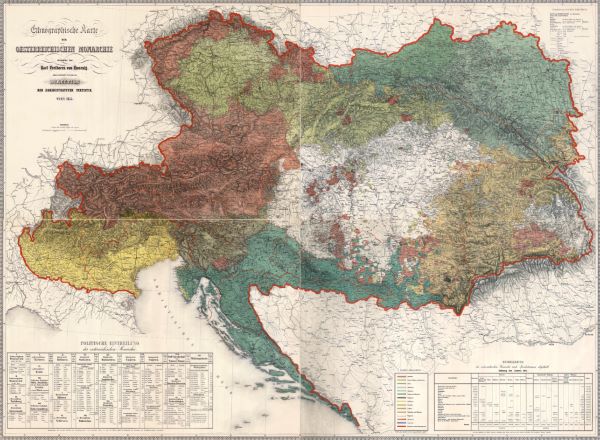

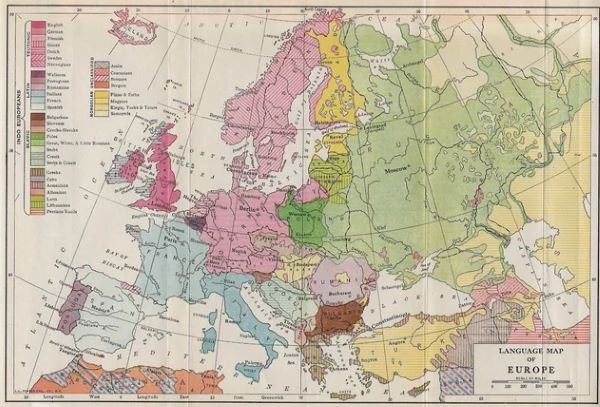

A look at a demographic map of nineteenth-century Europe shows that in terms of ethnicities or ethnic groups Western Europe was seemingly more compact while the greatest amount of ethnic fragmentation was to be found in Central and Eastern Europe. Such an impression is not completely erroneous, as indeed Central and Eastern Europe marked a region of the continent where several empires met and chafed at the edges. Imperial borderlands are usually much more ethnically complex. However, what a demographic map hides is the complex reality of ethnicity throughout west and east. Well into the nineteenth century, groups that might otherwise be represented as compact (the Germans, the French, the Italians) did not in practice represent one single ethnicity but rather myriads of regional dialects, local cultures, and worldviews, sometimes mutually unintelligible and foreign to one another.

This subchapter is going to investigate European patterns of interethnic experiences and state policies. The first section will concentrate on the ways ethnic groups were viewed in the emerging modern nation-states of nineteenth-century Europe, focusing on the links between state-building and homogenisation efforts as well as on the relationship between majority and minority groups. The second section will explore multi-ethnicity and multi-national empires in Central and Eastern Europe, concentrating on the Habsburg Monarchy as a paradigmatic example. The Jewish case will be presented in a separate section as a special category of minority experiences.

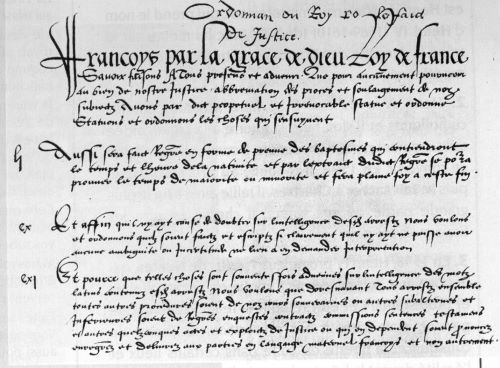

The Emergence of Modern Nation-states and the Changing Position of Ethnic Minorities in the Nation-state Paradigm

By the end of the early modern period, the common use of one dominant language had become the norm in several European monarchies. Although not all nineteenth-century states strove to achieve language homogenisation, most of them worked toward the marginalisation of minority languages in one way or another and strove to curtail the autonomy of historic minorities. In France, a country which served as a model for many emerging nation-states of nineteenth-century Europe, the centralisation of state power had progressed hand-in-hand with policies of language homogenisation since the early modern period. The 1539 Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts declared that French should be used exclusively in state administration and legal documents, as the only official language of the country. The French Revolution continued this tendency: linguistic diversity was interpreted as a risk to national unity, so the official use of regional languages (such as Occitan in the south, Celtic-influenced Breton in the north, and Basque near the French-Spanish border) was suppressed together with the local autonomies and ancient legal privileges of historic regions, which were all integrated into the uniform system of départements. With the emergence of nationalism and the ideal of the nation-state in nineteenth-century Europe, efforts in favour of cultural homogenisation became pronounced in several other European states as well. Education was seen as a particularly effective tool for transforming domestic populations into modern nations. The task of schools was, among other things, to raise good citizens and instil patriotic feelings in children. Therefore, educational systems were centralised in the course of the nineteenth century and ‘state languages’ assumed an increasingly dominant role in schools at the expense of minority languages. In 1880, for example, a nationally uniform school system was introduced in France, which left little or no room for regional languages.

However, even in countries with one dominant official language, a diversity of dialects prevailed, local languages survived, and significant ethnic minorities or nationalities continued to exist. The United Kingdom, officially the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 1801, is a case in point; despite the common language, it has never become a nation-state per se. In nineteenth-century Britain, the Irish, Welsh, Scots and smaller ethnic groups lived alongside the English and maintained their separate identities. These ‘nations’ were all peoples of Celtic origin, descendants of the population that had lived on the British Isles since before the Anglo-Saxon conquest.

Several members of those communities continued to use their own languages, although their struggles to ensure the survival of their native tongues were fought with varying degrees of success. In Ireland, Wales and Scotland, for example, the native Gaelic languages had long lost their primacy by the nineteenth century, and either bilingualism or the exclusive use of the English language had become the dominant pattern.

In nineteenth-century Spain, centralising tendencies followed the French model in many respects. The historic rights of significant minorities like the Basques were gradually suspended throughout the late eighteenth century and the nineteenth, and Spanish was declared to be the main language of the state. Nonetheless, regional cultural identities such as that of the Basques, Catalans and Gallegos proved to be strong enough to withstand the Spanish monarchy’s centralising ambitions, and their languages survived, transforming into modern languages during the nineteenth century.

In countries that achieved unification in the second half of the nineteenth century, like Italy in 1861 or Germany in 1871, common language and common cultural heritage were regarded as the chief unifying factors. However, strong dialectal differences and regional identities survived in these countries, thanks to centuries of territorial and political separation. It was to some extent a matter of decision which dialect should become the basis of standard German and standard Italian (and thus the language of state administration, the judiciary, middle and higher education, literature, and the press), and dialects continued to be spoken locally at work, in public, in informal social situations, and in families. On the other hand, both modern Italy and Germany were conceived as nation-states, and, at least in Germany, there was perceptible pressure on minorities—such as the Poles in the eastern provinces—to assimilate.

In binational states or dynastically connected countries with two large nations, ethnic relations and issues of national identity were complicated in a different way. In the nineteenth century, countries and regions continued to change hands in Europe as the result of wars and subsequent treaties by which rising powers satisfied their expansionist ambitions. For example, Denmark and Norway formed a dual monarchy together from 1537 to 1814, which also contained Iceland, Greenland, and the Faroe Islands with their native populations and languages. But then Norway was ceded to Sweden in the Treaty of Kiel in 1814. As Norwegians refused to accept this solution and declared their independence, a personal union (i.e., two countries joined by the person of the monarch) with Sweden was created as a compromise, lasting until 1905. In a country like Denmark-Norway, linguistic differences among the major ethnic communities were not exceedingly sharp, as the languages remained fairly close to each other until the end of the early modern period and even beyond. At the same time, Danish clearly dominated in official usage until 1814. So the nineteenth-century Norwegian cultural renaissance—very similar in nature to kindred revivalist movements in early nineteenth-century East Central Europe and other peripheral areas of the continent—did not merely strive to make the Norwegian language more distinct from the other Scandinavian languages by purification (for example, the replacement of ‘foreign’ loan words by indigenous ones) and spelling reforms, but was also faced with the task of having to create a modern literary language.

In other cases, new, ethnically compound countries were created from territories which had previously been ruled by other monarchies. Following a revolution in 1830, Belgium, formerly part of the Protestant-dominated United Kingdom of the Netherlands, was created in 1830 as an independent, bilingual country, comprised of Dutch-speaking Flemish and French-speaking Walloon inhabitants.

Multi-Ethnic Empires

Throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, large parts of Central and Eastern Europe formed portions of multinational and multi-ethnic empires, namely the Habsburg Monarchy and the Russian Empire. A third imperial power, the Ottoman Empire, ruled the peoples of the Balkans, and although it was increasingly forced to give up control over territories during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it controlled a substantial part of south-eastern Europe for much of the period discussed in this chapter. As mentioned above, the German Empire also included significant non-German populations as the result of Prussia’s territorial acquisitions in earlier centuries.

Unlike states in Western Europe, empires in the eastern part of the continent remained ethnically diverse until the end of the nineteenth century and even beyond. Many historical reasons stood behind that. Firstly, the empires of nineteenth-century Central and Eastern Europe had been formed over the centuries of ethnically and culturally diverse lands, which often adhered to their own political traditions and institutions and were linked together by ruling dynasties. Secondly, the policies of assimilation by the state elites appeared relatively late, in the late eighteenth century in Austria and even later in Russia. Thirdly, in some places such as the Ottoman Empire or the Baltic region in Russia, language diversity also served as a social barrier imposed by the ruling classes on the masses. Less advanced economies and relatively underdeveloped systems of communication and transport also hindered stronger assimilation. The ethnic map was therefore particularly diverse. More importantly, the power relations between states and ethnic groups (as well as among ethnic groups) varied widely and tended to change over time.

An Example of a Multi-Ethnic Empire: Ethnic Relations in the Habsburg Monarchy

Until the emergence of national movements in the first half of the nineteenth century, the multi-ethnic character of the Habsburg Empire did not cause serious difficulties for Habsburg governments, nor did it lead to conflicts among diverse ethnic groups. Emperor Joseph II (r. 1780–1790) promoted the German language as a lingua franca in the Habsburg Empire, regarding it as a tool of efficient centralisation, provoking a resistance that can be interpreted as a sign of rising national consciousness in various parts of the empire. Apart from that, however, the Habsburg governance of diverse areas rested on a degree of respect for local languages, religions, cultural and political traditions.

Early nineteenth-century movements of ‘national awakening’, as they were called in Central and Eastern Europe, were primarily cultural movements, but they gradually acquired stronger political overtones. The ideology of modern nationalism was intertwined with liberal ideas; the peoples of the Habsburg Monarchy were no longer content with the political system of the centralised empire and its absolutist government and demanded greater individual rights and freedoms, as well as collective rights and autonomies. Linguistic and cultural communities increasingly defined themselves as nations. Emerging national movements within the Habsburg Empire often had conflicting goals and interests and could be consciously pitted against each other by Austrian governments—as the revolutionary events of 1848–1849 amply demonstrated.

In 1867, the Austro-Hungarian Compromise created the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy (the official name of the Habsburg Empire between 1867 and 1918) and established parliamentarism in both halves. In the Austrian half of the Monarchy (Cisleithania), the constitution of 1867 secured rather generous ‘national’ rights for the corresponding ethnic groups. In addition, voting rights in Austria were gradually extended by electoral reforms in the late nineteenth century, while universal manhood suffrage (the right of all adult male citizens to vote) was introduced in 1907. As a result, the demands of nationalities were increasingly articulated in the Imperial Parliament, causing severe tensions. In the constitutionally autonomous Hungarian Kingdom (Transleithania), voting rights remained limited to a narrow circle of around six percent of the adult population, and ethnic minorities were severely underrepresented in Parliament. Although the rights of nationalities were stated in an important law of 1868, state policies in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Hungary were a de facto curtailment of minorities’ cultural and linguistic rights, and especially from the mid-1890s these policies strove to forcefully assimilate non-Hungarians. All this together led to an increasingly strained relationship between the Hungarian state and members of national and ethnic minorities. The ‘nationality problem’ thus plagued domestic politics in both halves of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy and contributed substantially to its dissolution in 1918.

Still, the constellations were diverse. In Bohemia, the rise of the Czech nation, markedly visible already during the revolution of 1848, led to intense struggle with an outnumbered yet economically strong German minority, which benefited from Germanophone networks and the German character of the Austrian state. In the province of Galicia, both Ruthenians and Poles were given broad space for their respective national activities. But it was the Poles, better-positioned in society, who assumed political control of the province.

The sense of belonging to a distinct ethnic community was arguably stronger in cases like those of the Czechs and the Poles, who could rely upon a long literary tradition in their own printed language and a legacy of statehood. The latter was still very much alive in the Polish case, while the ethnic identity of other peoples, such as Ukrainians or Slovaks, was weaker at the threshold of the ‘age of nations’. But even among these groups, ethnic identity was not simply out there, waiting to be taken to the fore by nationalists. Rather, national movements helped define and reinforce ethnic identities in the first place, building upon existing cultural markers such as language or religion. Ethnic identity was often unclear for many people, not to mention irrelevant to their everyday lives. Many people spoke two or more languages and switched depending on the situation, while identifying themselves primarily by profession, social status, place of living, or confession rather than ethnicity or nationality. Polish peasants, for instance, for a long time had little interest in the efforts of the Polish nobility and gentry to restore the Polish state, as class antagonisms rather than shared ethnicity defined their relations with one another well into the late nineteenth century.

As the century progressed, people were increasingly forced to belong to neatly divided ethnic groups. In the Habsburg Monarchy, modern censuses were introduced in 1869 and became powerful tools in this regard. The ‘language of daily use’ (Umgangsprache, used as a technical term in Austrian statistics) became an indicator of one’s ethnic belonging. Census data, in fact, often concealed bilingualism or the use of multiple languages, and were unable to reflect hybrid identities, shifting allegiances, and the complex situation of people with mixed ancestry. From the perspective of nationalist agitators, however, individuals characterised by national indifference or ‘ambiguous’ identities were seen with growing disdain. On a different level, ethnic features were appropriated in newly invented national traditions and symbols (such as national costumes) or studied, classified and displayed in the newly founded ethnographic museums and exhibitions.

Apart from political and intellectual struggles in state-wide arenas, interethnic relations played out in local spatial frameworks. In multi-ethnic regions, but sometimes in more homogeneous ones too, larger towns and cities were often multi-ethnic and multi-confessional. Lviv/Lwów/Lemberg, the capital of Galicia, for example, was comprised of Ruthenians, Poles, Jews, and Austrian Germans, while Timişoara/Temesvár/Temeswar/Temišvar had Romanian, Hungarian, ethnic German, Serbian, Slovak, Jewish, and Ruthenian inhabitants in the late nineteenth century. Ethnically mixed cities were the rule rather than the exception in several parts of the region. Ethnic maps of the period can therefore only provide an approximate image of regional and subregional colourfulness and do not sufficiently reflect the actual complexity of local conditions. In addition to the local ethnicities, cities in the Austrian half of the empire would also include German-speaking officials of the imperial administration.

Mass migration often thoroughly altered the ethnic composition of nineteenth-century cities while transforming their social structure. Some of the major regional capitals, such as Prague or Lemberg (in Polish Lwów, present-day Lviv, Ukraine), became centres of competing national movements laying claims to public space. Efforts by Czech elites to seize and symbolically recast Prague as a Czech city, and of Polish elites to sustain Lemberg’s image as a Polish city, were contradicted by “the politics of ethnic survival” (as described by historian Gary Cohen), practised by the vital minority of Germans in Prague, and by the growing presence of Ukrainian claims in the capital of Austrian Galicia. At the street level, territories and places were symbolically appropriated, such as the ‘Czech’ or ‘German’ promenades that stretched westwards and eastwards from Prague’s Wenceslas Square.

It would be misleading, however, to imagine fin-de-siècle cities as divided or even segregated. Interactions among members of different ethnic groups often took place on a daily basis, in spaces of leisure, work, and consumption—despite nationalist agitation encouraging people to follow precisely the opposite strategy. Members of ethnic communities were urged to shop with ‘their’ retailers and to avoid mixed marriages. However, many individuals, such as some of the leftist or Jewish intellectuals, deliberately crossed these ethnic boundaries.

Jews in Nation-States and Empires: Ethnicity or Denominational Minority?

When it comes to interethnic relations, the position of the Jewish population deserves special attention. Even though, statistically speaking, they were regarded as a religious group and not an ethnicity in most European countries by the late nineteenth century (with the exception of the Russian Empire), they were perceived as an ethnoreligious group by many contemporaries as well as by several members of Jewish communities themselves—especially the Orthodox. Assimilated Jews, on the other hand, tended to identify themselves in the second half of the nineteenth century primarily as members of one of the European nations or of linguistic-cultural communities such as English, French, Germans, Hungarians, and so on, depending on location and first language. The legal emancipation of Jews, which occurred at different times in different countries (1789 in France, 1812 in Prussia, 1867 in the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, 1917 in Russia), theoretically created the possibility of full social integration for Jews. However, the success of the integration process depended significantly on the social, cultural and political environments of individual countries. Whereas the social integration of Jews reached generally high levels in Western and North-western Europe, antagonisms were much more likely to prevail in east-central and Eastern Europe, where the proportion of Jews was significantly higher than in the western half of the continent. Not all segments of non-Jewish society accepted Jews in their ranks, and antisemites often called into question their Jewish compatriots’ national loyalties as well as their sincere identification with their homelands. Modern antisemitism, often and increasingly combined with racial theories by the turn of the twentieth century, had complex ideological, social and cultural roots, which cannot be analysed here in detail. But the persistence of antisemitism in modern European societies had grave consequences later on in the interwar period, when authoritarian or totalitarian regimes emerged across much of Europe.

In Russia, Jewish emancipation did not occur until 1917. Until the early twentieth century, Jewish citizens were confined by law to the Pale of Settlement, a large territory in the western part of the Russian Empire where they were mandated to reside, and which they could leave only on certain conditions. In other European areas, east-central Europe included, residential restrictions affecting Jews had been abolished by the 1850s at the latest. They had to endure various forms of popular as well as state-sponsored antisemitism, including periodic pogroms, which were among the main reasons for large-scale Jewish emigration from Russia after 1881.

Conclusion

The ethnic map of Europe at the turn of the nineteenth century was diverse and characterised by time-honoured patterns of coexistence. With the emergence of modern forms of nationalism, however, multi-ethnic and multi-cultural states as well as their resident ethnic groups were faced with new challenges. Efforts to transform countries into modern states often led to assimilationist policies and the attempted marginalisation of ethnic minorities. In absolutist regimes, ‘national’ demands for greater representation erupted in revolutions; by mid-century, national and ethnic tensions assumed different forms in constitutional monarchies. In bi- or multi-national states, competing nationalisms caused severe political tensions in the late nineteenth century and undermined political stability (even where minority rights were guaranteed by law).

One would assume that competing nationalisms provoked increasingly bitter conflict within local and urban communities in the second half of the nineteenth century too, but that would be a misunderstanding of the complexity of local conditions. Nationalist agendas were articulated in the public space, in the press, in associations, and in parliament, but at the same time, long-standing practices of interethnic communication and coexistence continued to characterise everyday life on the local level.

In the age of mass migration, the proximity of old and new ethnic groups, the appearance of culturally different ‘newcomers’, and particularly the rapid change which altered the former ethnic and linguistic composition of towns and cities, all together created the potential for conflicts within urban societies. However, larger cities also functioned as crucibles where the linguistic and cultural assimilation of minority groups proved much faster than in ethnically homogeneous, isolated regions.

Interethnic Relations in Contemporary History (ca. 1900–2000)

By Dr. Jarsolav Ira

Research Coordinator, Comparative Modern History

Institute of World History

Charles University

By Dr. Thomas Schad

Department of History

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin

By Dr. Erika Szívós

Associate Professor of History

International Commission for the History of Towns

Overview

Interethnic relations and the complex relationships among states, nations, and minority populations underwent several changes in twentieth-century Europe. The First World War brought about the dissolution of empires on the continent, the rearrangement of European borders and the emergence of entirely new states, especially in the continent’s eastern half. These geopolitical changes often thoroughly redefined the populations of European states as well as the possibilities for minorities within them. Dictatorships and authoritarian regimes in the interwar period fostered racialised thinking and the persecution of ethnic and other minorities, culminating in genocide and ethnic cleansing during and after the Second World War on a scale that would have been unimaginable a century earlier. Even in the second half of the twentieth century, discriminatory practices towards minorities continued and nationalist or separatist movements re-emerged, leading to periodic outbursts of violent interethnic conflicts. The remainder of this chapter will examine the ambiguity of the term ‘ethnicity’ and the changing relationships between majority and minority populations in Europe, with a particular focus on the more complex situation in multi-ethnic regions of Central, Eastern, and south-eastern Europe.

Ethnicity, Nationality, and Markers of Identity

Ethnicity and ethnic groups are often equated or confused with nationality, national minorities, or even nations. While these categories do overlap, they are not necessarily identical. To take but one example, the Socialist Federative Republic of Yugoslavia (1945–1992) drew a distinction between nation (narod, nacija) and nationality (narodnost), with the former term applying only to Serbs, Croats, Slovenes, Muslims, Montenegrins, and Macedonians, all of whom spoke Slavic languages and were considered the ‘constitutive people’ of the multiethnic state. However, residents of the same state who identified as Hungarian, Albanian, Romani, Jewish, Czech, German, Romanian, Bulgarian, Slovak, Turk, Rusyn, Italian, Vlach, or otherwise, were considered to belong to a nationality (narodnost) instead, implying that their ‘true’ homeland lay beyond the borders of Jugoslavija (literally “the land of South Slavs”).

Across Europe in the twentieth century (as in earlier periods), a commonly accepted, uniform definition of ethnicity never emerged; most often, the term was related to markers of difference such as religion, language, origin, culture, or some combination of these attributes. Religion, for instance, is still a decisive feature of identity in Northern Ireland: according to the 2011 census, the majority of Roman Catholics (57.2 percent) identified as Irish, while most Protestants (81.6 percent) declared themselves British. In the Balkans, religious affiliation is often the most prominent marker before language, as the case of Bosnia-Herzegovina shows, where Bosniaks—known until 1993 as Muslims (Muslimani)—are traditionally Sunni Muslims, whereas Serbs are Orthodox Christians, and Croats are Roman Catholics. However, the situation is radically different in nearby Albania, where Muslim, Orthodox, Catholic, Bektashi, and atheist Albanian speakers identify as Albanians, regardless of their respective religious traditions.

Language is the decisive identity marker for Germany’s Slavic-speaking Sorbs as well as for Frisians, who speak a Germanic dialect. In Spain and France, the Basque minority speaks a language unrelated to that of the dominant, surrounding communities. In Belgium, the two major population groups speak either French or Flemish, but neither is usually referred to as an ‘ethnic group’—instead, they are mostly referred to as Walloons and Flemings, or collectively as Belgians. This example from the European Union’s institutional centre draws attention to the widespread Eurocentric habit of applying the label of ‘ethnicity’ overwhelmingly to marginalised and minority groups—particularly outside of Europe and in supposedly peripheral regions such as the Balkans—but not to larger groups and majority populations in (Western) Europe.

In other cases, like the Swedish, Norwegian, and Sámi peoples of Scandinavia, ethnicity is not only marked by linguistic difference, but also by reference to different origins and origin myths. Cultural difference might be associated with religious difference, as in the case of Bulgaria’s Muslim Turkish minority. However, for the Sarakatsani people of Greece, North Macedonia, Bulgaria, and Albania, cultural difference is associated with a nomadic lifestyle. Nomadism became highly exceptional towards the end of the twentieth century in Europe, although it remains a stereotype associated with Europe’s largest ethnic minority, the Romani people. However, they use different names (such as Roma and Sinti, Ashkali, Lovari, Kale, Calé, and many others), they speak their own (Romani) and/or other languages, and they follow various religious traditions. The Romani people are present in every European country, from Finland in the north to Andalusia in the south. Throughout the twentieth century, they were stigmatised in various ways, from the names given to them by outsiders to open forms of racism and persecution, which peaked during the Second World War. Estimations by Romani organisations of their total population size in Europe vary between ten and fourteen million. Spain has the largest Roma population in Western Europe (725,000–750,000), whereas other significant centres are in the Balkans.

Ethnic Relations in Europe ca. 1918–1945

As these examples show, it is extremely difficult to grasp Europe and its interethnic relations across the twentieth century from only one perspective. It is nevertheless possible to draw a distinction between developments in the western, south-western, and northern parts of the continent on the one hand, and the central, eastern, and south-eastern parts on the other. In Western Europe, a consolidation of nation-state structures accompanied by ethnic homogenisation took place earlier than elsewhere (though often later than commonly assumed). In Central and Eastern Europe, stretching from present-day Poland, Czechia, Slovakia, Austria, and Hungary eastwards to the western Balkans, ethnic diversity within the spaces of former multi-ethnic empires persisted much longer. Whether it was the Austro-Hungarian, the Ottoman, or the Russian Empire, all of these pre-national political structures were intrinsically multi-ethnic.

The difference between mostly mono-ethnic nation-states and multi-ethnic empires also helps to explain why inter-ethnic violence and tensions often arose in areas which became nation-states comparatively late: the logic of nationalism stresses the alignment of territory, population, and political power (sovereignty) within one ‘nation’. According to this logic, ethnic difference can easily turn into violent conflict over resources, especially when new borders are drawn, new state bureaucracies emerge, or when citizenship is redefined along linguistic, religious, or other ‘ethnic’ criteria. Nationalist regimes homogenised populations through policies of ‘social engineering’ that reshaped their demographic or ethnic composition, such as through ethnic cleansing, forced resettlement, assimilation, or genocide.

While ethnic diversity in Eastern and Central European states was commonplace before 1918, the ‘Versailles System’ established after the First World War created radically new conditions. The dissolution of the multi-ethnic empires (Austria-Hungary, Russia, Wilhelmine Germany, the Ottoman Empire) was followed by the emergence of successor states whose legitimacy derived from the principle of national self-determination. But the new states were far from ethnically homogeneous units and many ethnic groups found themselves dispersed outside of ‘their’ nation-states.

Incongruencies between cultural and political borders fostered major tensions both within and beyond individual nations during the interwar period. Domestically, relationships were often strained between national minorities and the majority populations (the so-called ‘titular nations’) that became hegemons of their respective states. At the same time, national groups became bones of contention between the states in which they formed a minority (such as Germans in Czechoslovakia or Hungarians in Romania) and the states where they were dominant (Germany, Hungary).

Legal measures were created to secure the rights of national minorities, such as those enshrined in the Minority Treaties that newly established states were obliged to sign in order to join the League of Nations. The League served as arbitrator in cases of alleged mistreatment of minorities, but cases could only be put forward by the recognised nation-states that were members of the organisation. In practice, many new states imposed the cultural dominance of the largest ethnic group and treated minorities that did not assimilate as unreliable or disloyal.

Some states, such as Poland, adopted harsh policies toward minorities, enacting measures of cultural Polonisation while excluding minorities from state structures. This especially applied to Ukrainians, Belarussians, Jews, and Germans, who together formed roughly one third of the population. Czechoslovakia adopted a more liberal attitude towards its German, Hungarian, Ruthenian, and Polish minorities, but still regarded these groups’ demands for greater cultural or territorial autonomy with suspicion. The peculiar and instrumental construction of a ‘Czechoslovak’ nation itself concealed the unequal relationship between Czechs on the one hand and Slovaks on the other, with the latter remaining underrepresented in state administration and public institutions.

Mid-Century Transformations

The Second World War and its aftermath brought about a profound transformation of Central and Eastern Europe’s ethnic conditions. The war itself triggered the flight and emigration of hundreds of thousands of people from territories invaded or annexed by Nazi Germany and its allies. The largest proportion of the refugees were Jewish by religion or by descent, but non-Jewish citizens also had reason to fear persecution on ethnic or political grounds, and thus fled in large numbers from countries like occupied Poland in 1939. As the war continued and the Nazis pursued a policy of extermination towards Jews, millions of people in Central and Eastern Europe were murdered. Jewish emigration from the region during and after the war thoroughly changed its composition and culture, as characteristic groups and urban subcultures disappeared and the complex ties between Jews and Gentiles were broken.

Similar movements of mass flight and forced migration unfolded in the other direction as well. In 1939, following the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact signed by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, the Soviet Union annexed eastern Poland, and in 1940 forced the Baltic states to join the USSR. The Nazis themselves forced Baltic Germans, who had inhabited the region since the Middle Ages, to resettle within the Third Reich. As the Soviet front approached, the ethnic German population of East Prussia (today the Kaliningrad exclave of Russia) was evacuated en masse, never to return to their former homeland. At the end of the Second World War, the Allies instituted wartime agreements that led to substantial border changes in Central and Eastern Europe, which were often accompanied by ‘population exchanges’—mass expulsions that forced several million people to relocate. To take Poland as an example: Germans were expelled from the western territories incorporated into post-war Poland, while Polish citizens were forced to move out of the areas ceded to the Soviet Union. Simultaneously, a similar number of ethnic Belarussians and Ukrainians had to leave Poland and move to the neighbouring Belarussian and Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republics, areas which by then had become permanent parts of the Soviet Union.

Almost everywhere in Eastern and Central Europe, the guiding principle behind expulsions and population exchanges was the drive of post-war governments to transform their countries into ethnically homogeneous states, an idea that was initially supported by all Allied powers as well. However, given the ethnic, linguistic and denominational diversity of Central and Eastern Europe and the ethnic complexity of many of its sub-regions, homogeneity in most cases could only be achieved—if at all—by coercion. For example, under a so-called population exchange treaty in 1946, ethnic Hungarians from Czechoslovakia and ethnic Slovaks from Hungary could ‘swap’ their domiciles; however, the figures on the two sides did not match (approximately 120,000 resettled Hungarians vs some 73,000 resettling Slovaks).

Expulsions and forced resettlement, designed partly to solve the ‘nationality problem’ and partly to administer collective punishment, disrupted age-old patterns of coexistence. By placing people into rigid ethnic or national categories, expulsions often targeted those who had compound identities and those with multiple ties to their country and its communities.

Minority Issues and Policies during and after the Cold War

Although states in post-war Central and Eastern Europe perceptibly worked towards the greatest possible degree of homogeneity, several countries retained a multi-ethnic character and/or ethnic minorities after 1945. Policies regarding minorities varied from state to state and from period from period. After the communist takeover, the Marxist doctrine of ‘proletarian internationalism’ to some extent relegated minority issues into the background, but ethnic realities still had to be addressed. The USSR was itself a multi-ethnic state in which contradictory policies coexisted. While Russification and the suppression of local nationalisms was a marked tendency during the entire history of the Soviet Union, so too was a whole range of working solutions developed with regard to the languages of member republics and the historic and cultural heritage of non-Russian nationalities. The countries of the Socialist Bloc were required to adopt the principles of proletarian internationalism, but at the same time they could look to the Soviet Union for practical examples of how to handle nationalities within a multi-ethnic communist state. In some east-central European communist countries, such as Hungary and Yugoslavia, the equality of all nationalities was stated in the constitution; in others (Czechoslovakia for instance), the rights of nationalities were regulated by various laws.

However, state socialism did little to cultivate the allegiances of minorities. Communist governments required citizens to identify primarily with the party and the state, usually regarding all other loyalties and identities with suspicion. Where national minorities were permitted their own institutions (such as schools, cultural associations, organisations, events, newspapers, or regular radio and television programmes), these were closely monitored and kept under strict state control. The case of the Roma in Czechoslovakia is illustrative of the contradictory approach toward minority groups under socialism. On the one hand, the state pursued assimilation strategies premised on the idea that the Roma did not constitute a distinct nationality, but rather represented a kind of ‘deviant’ lifestyle or a social problem for the state. Measures deployed against the Roma included not only continuous sedentarisation and resettlement (from the countryside of eastern Slovakia to cities in the border regions of Bohemia), but also much more aggressive policies such as the sterilisation of Roma women or segregation of Roma children into ‘special schools’. On the other hand, the proclamations of equality and extensive social rights that legitimised the socialist regime also created a space for advocating for the rights of Roma, their inclusion in society, and their recognition as a nationality.

As far as Western Europe was concerned, intercultural issues underwent significant changes after the Second World War as, for the first time in modern history, Europe became a continent of mass inward migration. In the wake of decolonisation, an ever-larger number of non-Europeans arrived from former colonies to countries like Britain, France, and the Netherlands. In the economic boom that began in the 1950s, large numbers of so-called ‘guest workers’—initially from Italy, Spain, and Portugal, then increasingly from Turkey and Yugoslavia—were recruited for employment in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. By the 1990s, immigration had greatly diversified in terms of the motivations of migrants and their countries of origin. With the emergence of the European Community, later the European Union, intra-European migration began to increase as well. These new patterns of migration raised new kinds of concerns. Cultural differences, manifest in residential spatial patterns such as segregation, and new issues of cultural integration began to define discourses on interethnic relations.

The collapse of state socialist regimes in 1989–1990 put the question of minorities on a new footing. Democratically elected parliaments and post-1990 governments sought to create legal frameworks in which minority rights were respected and observed. In many cases, these new laws were shaped by the European Union, which expanded to include the Visegrád countries (Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Hungary), the Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania), as well as Slovenia in 2004, followed by Romania and Croatia three years later. Minorities in these countries thus obtained greater legal protections. However, populist and right-wing nationalist parties claiming to represent the entire ‘nation’ (meaning, in fact, the majority ethnic population) also pursued aggressive policies against minorities in this period. In some countries, unbridled nationalism led to increasing tensions and discrimination in everyday life.

In the aftermath of the Cold War, Europe was also reminded of the dangers of violent interethnic conflict. The breakup of Yugoslavia in 1991 and the subsequent wars in Croatia (1991–1995), Bosnia-Herzegovina (1992–1995), and Kosovo (1998–1999) represented the first large-scale interethnic wars on European soil since the Second World War. With the fall of the Muslim enclave of Srebrenica (Bosnia) on 11 July 1995, the war even led to the first post-1945 genocide in Europe, against the Bosniak people. These conflicts shared many similarities with those earlier in the century, when the disintegration of multi-ethnic states had led to struggles between competing ethnic groups for sovereignty over ‘their’ territory.

Conclusion

After the First World War and the dissolution of former empires, national ideals informed the self-identification of new states, and continued to define the strategies of governing elites throughout the century. This development encouraged restrictive or assimilative policies towards national or ethnic minorities, fuelling unresolved tensions and in some cases leading to separatist movements. The period between the early 1930s and the late 1940s irreversibly changed the ethnic maps of entire regions. Millions were killed or forced to resettle as a result of the Second World War. War, genocide, and mass expulsions broke up centuries-old patterns of ethnic coexistence in the victims’ places of origin, while the arrival of forced migrants often led to new tensions with the local populace in their places of arrival. After 1945, Europe became a region of mass immigration due to post-colonial global migration patterns and the globalisation of the labour market. Until 1989, Eastern Bloc countries—being closed societies under the control of the Soviet Union—stood largely outside the circuits of global migration. However, after the collapse of state socialist systems, they too became countries of arrival for international migrants within an expanding European Union.

The ‘national turn’ that had taken place in the late nineteenth century thus manifested itself in all countries of Europe throughout the twentieth century, deeply affecting the relationship of majority nations with the minorities living among them, as well as the relationships between different minority groups. The ethnically and culturally homogeneous nation-state became the norm and the ideal, even if that ideal was far removed from the existing realities of most European countries, and particularly far from the conditions of large, multi-ethnic states in early twentieth-century Europe. This was particularly true in Central, Eastern and south-eastern Europe, regions whose twentieth-century history exemplifies key problems of interethnic relations. Indeed, the habit of speaking about ‘ethnic groups’ is far more prevalent in relation to Eastern and south-eastern Europe than it is to Western Europe, though there exist important tensions in minority-majority relations in the latter as well. Conflicts over ethnic difference are thus not a specific feature of the east and southeast, but a reflection of the longevity of nationalist thought and its assumption of ethnic homogeneity. Given the bloodshed and body count of nationalist projects, one must use ‘national’ and ‘ethnic’ categories with care and critical reflection.

The most troublesome impact of the ‘national turn’ has been on minorities who have never had their own nation-state within Europe, such as Jews, the Roma, and nomads. The Jewish response to the experience of being a ‘stateless’ people was often a strong identification with, and an effort to integrate into, the state in which they lived. However, with right-wing political groups and exponents of racial ideologies repeatedly calling such efforts at integration into question, another Jewish response was the rise of political Zionism, an early twentieth-century modern nationalist movement that sought to (re)create a Jewish homeland outside Europe and encourage the emigration of European Jewry into that new state. The societal integration of the Roma, the Sinti and of various nomadic groups was similarly controversial and remained incompletely addressed in many European countries, even in the late twentieth century.

Suggested Reading

- Augustyniak, Urszula, History of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: State—Society—Culture, trans. by Grażyna Waluga and Dorota Sobstel (Frankfurt: Lang, 2015).

- Berger, Stefan, ed., A Companion to Nineteenth-Century Europe, 1789–1914 (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2006).

- Bookman, Milica Zarkovic, The Demographic Struggle for Power: The Political Economy of Demographic Engineering in the Modern World (London: Routledge, 2013).

- Burke, Peter, ‘Nationalisms and Vernaculars, 1500–1800’, in The Oxford Handbook of the History of Nationalisms, ed. by John Breuilly (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), pp. 21–35.

- Chu, Winson, The German Minority in Interwar Poland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012).

- Cohen, Gary B., The Politics of Ethnic Survival: Germans in Prague, 1861–1914 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981).

- Donert, Celia, The Rights of the Roma: The Struggle for Citizenship in Postwar Czechoslovakia (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017).

- Dursteler, Eric R., Venetians in Constantinople: Nation, Identity, and Coexistence in the Early Modern Mediterranean (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006).

- Eiler, Ferenc, Dagmar Hájková et al., Czech and Hungarian Minority Policy in Central Europe, 1918–1938 (Prague: MÚA AV ČR, 2009).

- Green Mercado, Mayte, ‘Ethnic Groups in Renaissance Spain’, in A Companion to the Spanish Renaissance, ed. by Hilaire Kallendorf (Leiden: Brill, 2018), pp. 121–140.

- Gyáni, Gábor, György Kövér and Tibor Valuch, Social History of Hungary from the Reform Era to the Twentieth Century (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004).

- Hansen, Lars Ivar, and Bjørnar Olsen, Hunters in Transition: An Outline of Early Sámi History (Leiden: Brill, 2013).

- Judson, Pieter M., The Habsburg Empire: A History (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press, 2016).

- Karady, Victor, The Jews of Europe in the Modern Era: A Socio-Historical Outline (Budapest: CEU Press, 2004).

- Kontler, László, A History of Hungary (Budapest: Atlantisz, 2008).

- Mironov, Boris and Ben Eklof, The Social History of Imperial Russia, 1700–1917 (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2000).

- Nirenberg, David, Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition (New York: Norton and Company, 2013).

- Rubiés, Joan-Pau, ‘Were Early Modern Europeans Racist?’, in Ideas of ‘Race’ in the History of the Humanities, ed. by Amos Morris-Reich and Dirk Rupnow (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), pp. 33–87.

- Salmi, Hannu, Nineteenth-Century Europe: A Cultural History (Oxford: Polity Press, 2008).

- Shahar, Shulamith, ‘Religious Minorities, Vagabonds and Gypsies in Early Modern Europe’, in The Roma – A Minority in Europe: Historical and Social Perspectives, ed. by Roni Stauber and Raphael Vago (Budapest: Central European University Press, 2007), pp. 1–18.

- Ther, Philipp, The Dark Side of Nation-States: Ethnic Cleansing in Modern Europe (Oxford and New York: Berghahn Books, 2014).

- Zahra, Tara, ‘Imagined Noncommunities: National Indifference as a Category of Analysis’, Slavic Review 69:1 (2010), 93–119.

- Zimmer, Oliver, Nationalism in Europe, 1890–1940 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003).

Chapter 2.2: Interethnic Relations, from The European Experience: A Multi-Perspective History of Modern Europe, 1500–2000, published by Open Book Publishers (02.06.2023) under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license.