Novels tapped into communal fears.

By Dr. Andrea Kaston Tange

Professor of English

Macalester College

Introduction

Modern medicine has enabled citizens of wealthy, industrialized nations to forget that children once routinely died in shocking numbers. Teaching 19th-century English literature, I regularly encounter gutting depictions of losing a child, and I am reminded that not knowing the emotional cost of widespread child mortality is a luxury.

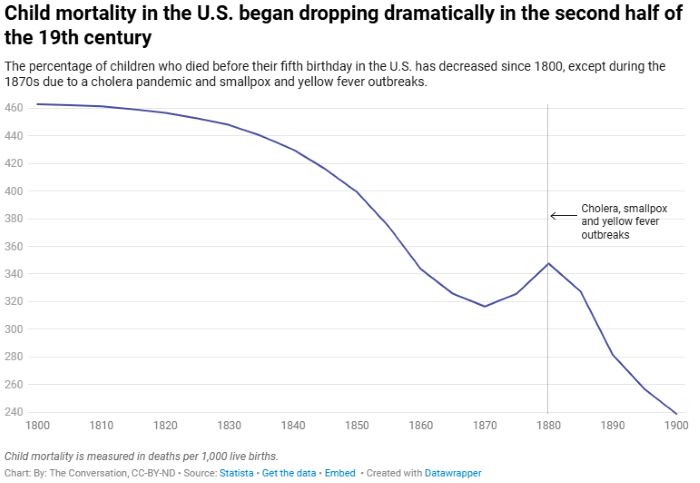

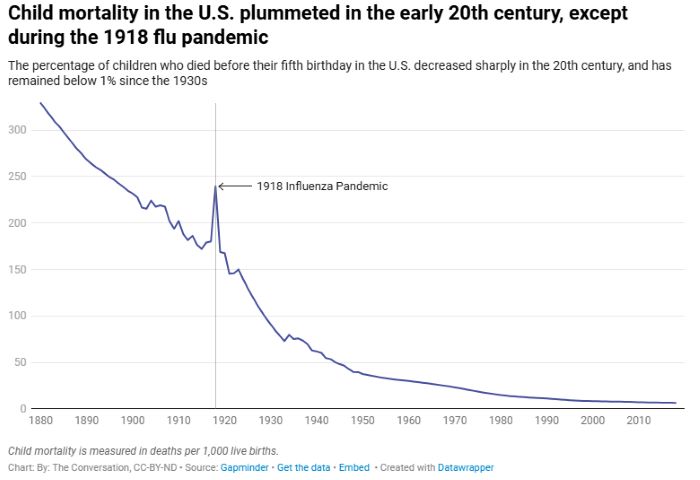

In the first half of the 19th century, between 40% and 50% of children in the U.S. didn’t live past the age of 5. While overall child mortality was somewhat lower in the U.K., the rate remained near 50% through the early 20th century for children living in the poorest slums.

Threats from disease were extensive. Tuberculosis killed an estimated 1 in 7 people in the U.S. and Europe, and it was the leading cause of death in the U.S. in the early decades of the 19th century. Smallpox killed 80% of the children it infected. The high fatality rate of diphtheria and the apparent randomness of its onset caused panic in the press when the disease emerged in the U.K. in the late 1850s.

Multiple technologies now prevent epidemic spread of these and other once-common childhood illnesses, including polio, tetanus, whooping cough, measles, scarlet fever and cholera.

Closed sewers protect drinking water from fecal contamination. Pasteurization kills tuberculosis, diphtheria, typhoid and other disease-causing organisms in milk. Federal regulations stopped purveyors from adulterating foods with the chalk, lead, alum, plaster and even arsenic once used to improve the color, texture or density of inferior products. Vaccines created herd immunity to slow disease spread, and antibiotics offer cures to many bacterial illnesses.

As a result of these sanitary, regulatory and medical advances, child mortality rates have sat below 1% in the U.S. and U.K. since the 1930s.

Victorian novels chronicle the terrible grief of losing children. Depicting the cruelty of diseases largely unfamiliar today, they also warn against being lulled into thinking that child deaths can never be inevitable again.

Routine Death Meant Relentless Grief

Novels tapped into communal fears as they mourned fictional children.

Little Nell, the angelic figure at the center of Charles Dickens’ wildly popular “The Old Curiosity Shop,” fades away from an unnamed illness over the last few installments of this serialized novel. When the ship carrying the printed pages with the final part of the story pulled into New York, people apparently shouted from the docks, asking if she had survived. The public investment in, and grief over, her death reflects a shared experience of helplessness: No amount of love can save a child’s life.

Eleven-year-old Anne Shirley of “Green Gables” fame became a hero for pulling 3-year-old Minnie May through a dramatic battle with diphtheria. Readers knew this as a horrendous illness in which a membrane blocks the throat so effectively that a child will gasp to death.

Children were familiar with disease risks. While typhus runs rampant in “Jane Eyre,” killing nearly half the girls at their charity school, 13-year-old Helen Burns is struggling against tuberculosis. Ten-year-old Jane is filled with horror at the possible loss of the only person who has ever truly cared for her.

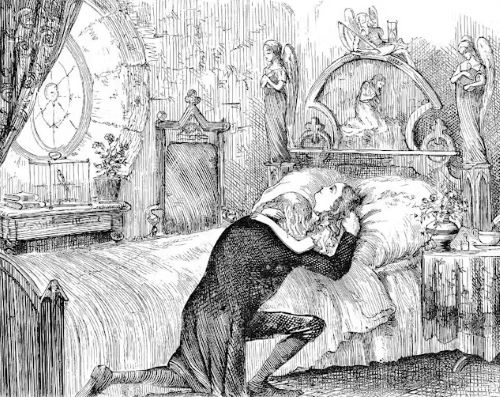

An entire chapter deals frankly and emotionally with all this dying. Jane cannot bear separation from quarantined Helen and seeks her out one night, filled with “the dread of seeing a corpse.” In the chill of a Victorian bedroom, she slips under Helen’s blankets and tries to stifle her own sobs as Helen is overtaken with coughing. A teacher discovers them the next morning: “my face against Helen Burns’s shoulder, my arms round her neck. I was asleep, and Helen was – dead.”

The disconcerting image of a child nestled in sleep against another child’s corpse may seem unrealistic. But it is very like the mid-19th-century memento photographs taken of deceased children surrounded by their living siblings. The specter of death, such scenes remind us, lay at the center of Victorian childhood.

Fiction Was Not Worse Than Fact

Victorian periodicals and personal writings remind us that death being common did not make it less tragic.

Darwin agonized at losing “the joy of the Household,” when his 10-year-old daughter Annie succumbed to tuberculosis in 1851.

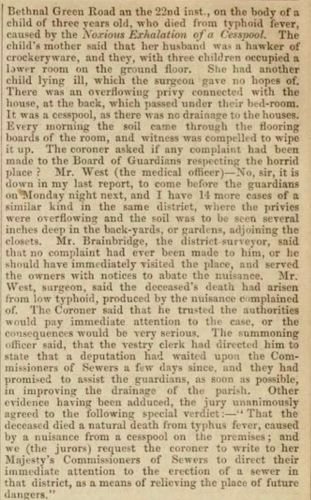

The weekly magazine “Household Words” reported the 1853 death of a 3-year-old from typhoid fever in a London slum contaminated by an open cesspool. But better housing was no guarantee against waterborne infection. President Abraham Lincoln was “convulsed” and “unnerved,” his wife “inconsolable,” watching their son Willie, 11, die of typhoid in the White House.

In 1856, Archibald Tait, then headmaster of Rugby and later Archbishop of Canterbury, lost five of his seven children in just over a month to scarlet fever. At the time, according to historians of medicine, this was the most common pediatric infectious disease in the U.S. and Europe, killing 10,000 children per year in England and Wales alone.

Scarlet fever is now generally curable with a 10-day course of antibiotics. However, researchers warn that recent outbreaks demonstrate we cannot relax our vigilance against contagion.

Forgetting at Our Peril

Victorian fictions linger on child deathbeds. Modern readers, unused to earnest evocations of communal grief, may mock such sentimental scenes because it is easier to laugh at perceived exaggeration than to frankly confront the specter of a dying child.

“She was dead. Dear, gentle, patient, noble Nell was dead,” Dickens wrote in 1841, at a time when a quarter of all the children he knew might die before adulthood. For a reader whose own child could easily trade places with Little Nell, becoming “mute and motionless forever,” the sentence is an outpouring of parental anguish.

These Victorian stories commemorate a profound, culturally shared grief. To dismiss them as old-fashioned is to assume they are outdated because of the passage of time. But the collective pain of a high child mortality rate was eradicated not by time, but by effort. Rigorous sanitation reform, food and water safety standards, and widespread use of disease-fighting tools like vaccines, quarantine, hygiene and antibiotics are choices.

And the successes born of these choices can unravel if people begin choosing differently about health precautions.

While tipping points differ by illness, epidemiologists agree that even small drops in vaccine rates can compromise herd immunity. Infectious disease experts and public health officials are already warning of the dangerous uptick of diseases whose horrors 20th century advances helped wealthy societies forget.

People who want to dismantle a century of resolute public health measures, like vaccination, invite those horrors to return.

Originally published by The Conversation, 12.11.2024, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution/No derivatives license.