Greeks were ‘the first to endure the sight of Median clothing and of the men wearing it’.

By Dr. Christopher Tuplin

Gladstone Professor of Greek

University of Liverpool

Introduction

When the army had been drawn up and the sacrifices turned out favourable, the Athenians were released and charged the barbarians at a run.1 The distance between the lines was no less than eight stades. When the Persians saw them attacking at a run, they began to prepare to meet them. But their view was that the Athenians were mad to the point of self-destruction, since they saw that they were few in number and were, moreover, coming on at a run with neither cavalry nor archers in support. So that was what the barbarians reckoned. But when the Athenians en masse came into contact with the barbarians, they put up a remarkable fight. For they were the first of all Greeks known to us to use a running-attack against the enemy, and the first to endure the sight of Median clothing and of the men wearing it. Until then even to hear the name ‘Mede’ was a cause of fear to Greeks.

Herodotus 6.112 is mostly famous – or infamous – for the statements that the Athenians were the first to do a running attack and that they did so over 8 stades. This is not my chief concern here, but by way of Priamel I make four observations. (1) Running is a way of having less time to be frightened by the enemy’s clothing. (2) Contemplation of a passage in Pausanias, Messeniaka (4.8.1), where running into battle is characteristic of the reckless passion of men fighting for freedom and their fatherland against a more numerous enemy and such men are said to be close to mad, suggests some readers thought the Athenians’ behaviour was due to their political situation not, as moderns have it, a desire to get through the arrow barrage as quickly as possible. (3) Marathon is not the only occasion on which Herodotus’ Persians think Greek combat-opponents mad. At Artemisium Xerxes’ soldiers and generals reckon the Greek challenge to battle a sign of madness, and (as at Marathon) the small size of the Greek fleet is implicitly the ground for this judgment (8.10).2 (4) No other Persian War battle involved a Greek running attack – but Herodotus’ account of Plataea makes the Persians attack dromōi (9.59). There are other vaguely contrary resonances between 6.112 and the Plataea narrative – the madness of Amompharetus, which made him stand still (9.53-57, esp. 55); repeated Greek shifts of position, as though they were afraid to confront the enemy; comments on the clothing, or at least the defensive weaponry, of the Persians (see below); superlatives that are not firsts (Pausanias won the fairest victory of all those we know of [9.64] and got greatest fame of the Greeks of whom we know [9.78]); and explicit allusion to the Athenians’ prior experience in 490 (9.27) – and I feel sure Herodotus’ introduction of a running attack is quite knowingly done.3 Marathon is rather under-narrated in Herodotus: the economy of his work does privilege 480/79 over 490.4 But 6.112 is a compensating explicit marker of the event’s status.

But my particular interest is the second part of the final sentence. The Athenians were the ‘first of all Greeks known to us’ to do a running attack, but they were also ‘the first to endure the sight of Median clothing and of the men wearing it.5 Until then even to hear the name ‘Mede’ was a cause of fear to Greeks’. This was not the first time Greeks had looked upon Persians and their clothing long enough to attempt to fight them,6 and certainly not the first time they had looked upon them in other contexts (Greeks cooperated with Persian military forces in Anatolia, Egypt, and Scythia),7 so the sentence is really a way of saying that this was the first time Greeks had confronted and defeated a Persian army. But, why not say that, instead of talking about clothes and a name? One sort of answer is that, although all of Herodotus’ readers doubtless knew who won at Marathon, it would slightly spoil the narrative effect to assert as much in the middle of the story. Herodotus needed an indirect way of putting it. But it is still worth unpicking some of the implications of the indirect approach he chose – and assessing how justified a choice it actually was.

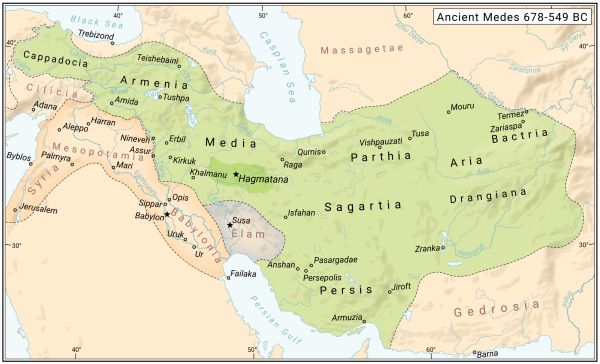

Median Name

Fear of a name is not, I think, a common trope;8 and the usage of ‘Mede’ in Greek confirms that there is something special about the word, since it is persistently used where ‘Persian’ would be expected. In a discussion published over 15 years ago I concluded that there was a strong tendency for this to occur when the focus is ‘on the empire as an alien, faceless military and political threat’.9 What lies behind this is the fact that the first Persian conquest of Greeks was perceived as the work of the Medes; and what lies behind that fact is the historical contiguity of Lydian and Median spheres of power in central Anatolia: when a conqueror from beyond the Halys captured Sardis and subjugated Ionia it was natural to call him a Mede – especially as his principal generals were Medes.

I still stand by this argument, but there are two problems, one for the substance of the argument, and one for the role 6.112 plays in it.10

The substantial problem is an Egyptian one. My position in 1994 was that Greek use of ‘Mede’ for ‘Persian’ was not properly paralleled in other western parts of the Achaemenid Empire and that there could therefore be an uncomplicatedly Anatolian explanation of the phenomena. It now seems to me that, in the light of material to hand (which exceeds what was available in 1994), one must at least leave open the possibility that ‘Mede’ was used for ‘Persian’ in pre-Hellenistic Egypt, especially in contexts that were remote from official ones and were concerned with the Persian threat to the country.11 How is one to square this with my Greco-Anatolian explanation of the frightening associations of the Median name in Greek contexts?

The ultimate historical starting point for Medes becoming an object of terror to anyone was their role alongside the Babylonians in the destruction the Assyrian empire.12 These were developments of direct interest to Egyptians; one direct consequence was the Egyptian attempt to occupy the Levant that was thwarted at Carcemish in 60513 and followed by Babylonian acquisition of the region. We can reasonably assume that from this era the Egyptians saw the geopolitical space to their north and east as defined by Babylonians and Medes. They should also have been aware that the erstwhile allies did not remain friends. From the Babylonian point of view land to the east and the north was a potential cause of trouble; Nabonidus represents Harran as vulnerable to the Medes in the mid-sixth century and Jewish prophets cast the Medes as a threat to Babylon.14 Meanwhile, there was active military confrontation between Lydians and Medes in Anatolia in the early sixth century (Hdt. 1.74). In short, the Medes, though distant, must have been part of the Egyptian world-picture. So, what did they make of it when Lydia and then Babylon succumbed to a conqueror from Iran? Babylonians knew who they were dealing with, as did Jews: neither group confused a historical Median threat to Babylon with the actual Persian (or Anshanite) conquest of the latter. Were Egyptians so precise? And what about Lydia? Croesus made an alliance with the Egyptian pharaoh Amasis (Hdt. 1.77). Did a Lydian perspective on the eastern conqueror influence Egyptian reactions to events in western Anatolia and southern Mesopotamia either side of 540 BC – events that actually represented an even greater geopolitical derangement than those that had occurred in northern Mesopotamia 70 years earlier? I suggest that it is possible that Egyptians were inclined to categorize this new upheaval in terms that had been appropriate throughout much of the intervening period – and that, under Anatolian and even Greek influence (for Egypt was full of Anatolian and Greek mercenaries), they continued to see things thus when their turn came in 526.15

My second problem brings us back to Herodotus 6.112. In 1994 I took the persistence of the use of ‘Mede’ for ‘Persian’ in contexts of threat to reflect a special aura of fear or horror surrounding the original conquest, a view for which 6.112 plainly seems to offer support. But is everything straightforward here?

On the one hand, there is certainly an element of demonization of Medes in Near Eastern texts. Isaiah 13.18 spoke of the ‘bow-bearing Medes who care nothing for gold and silver, only slaughter of young men and unborn children’, while many texts in Akkadian describe the Medes as Ummanmanda, an old term for fearsome eastern mountain-dwellers whose original meaning is perhaps ‘human? perhaps’ – with a decided implication that they are not.16

Did this attitude percolate through to Anatolians? I make two observations.

(1) The Medes were not the first easterners to disturb the peace of western Anatolia. That honour goes to the Cimmerians. Direct evidence about them is slight, but they evidently left a significant mark upon the collective historical memory: location of Cimmerians at the entrance to Hades in Odyssey XI is surely a sign of this. They are also visible in Near Eastern sources, and one such source describes Dugdamme (Lygdamis) as a ‘mountain king, an arrogant Gutian and the seed of halqate’.17 The seed of halqate are the Ummanmanda of the Cuthaean legend of Naram-Sin, so seventh-century Cimmerians were seen by Assyrians in terms similar to those used by Babylonians of sixth-century Medes. Moreover Lanfranchi has argued that, since the Ummanmanda of the Cuthaean Legend were bird-monsters appropriate to a Mesopotamian underworld, the Homeric location of the Cimmerians shows that Mesopotamian reactions to Cimmerians were transmitted to western Anatolia.18 If so, then might the negative stereotyping of Medes also have been transmitted at a later date? (2) The Herodotean image of Cyrus’ Iranians as the tough scions of a rugged land who know nothing of luxury (9.122) is in contrast to normal Greek perceptions of the Persians and may even, under a classical Greek veneer, distantly echo Mesopotamian views of men from the Zagros. Eventually a view of history emerged in which Medes were as luxury-loving as the Persians were reckoned to have become (a view reflected in Xenophon’s Cyropaedia),19 but this need not be what ‘Mede’ originally evoked – and one could say that, in terms of spectacular nastiness, the Thyestean feast served by Astyages to Harpagus (Hdt. 1.119) out-trumps the most horrible of Achaemenid behaviour. There is a remnant here too, perhaps, of a sense of Medes as demonic transgressors.

And yet there is a problem. The capture of Sardis must have been shocking, and supposedly involved much slaughter (Hdt. 1.80), even if Croesus was not then burned to death.20 The relentlessly successful sieges of Greek cities frightened even islanders into surrendering to the non-naval Persians;21 and Harpagus made lower Asia anastatos – a quite powerfully negative idea in Herodotean terms.22 But one cannot say that the Herodotean narrative of these things exactly luxuriates in the trauma of conquest. And the same is true down to 490, when Greeks were allegedly still afraid just of the name ‘Mede’. For example, the results of defeat for rebel Ionians were death, deportation, castration, and the burning of sanctuaries, but Herodotus does not dwell upon the details or colour his narrative here or elsewhere to evoke the image of an enemy from hell.23 It was quite reasonable to be afraid at Marathon: the Persians’ few unsuccessful land-battles had been against non-Greeks and Marathon would be the first time victorious Greeks were left in control of a battlefield full of dead Persians. But the starkness of the claim at the end of 6.112 may nonetheless be thought to come as something of a surprise.

Median Clothes

I shall leave that thought hanging for the moment, and move to the issue of clothing.

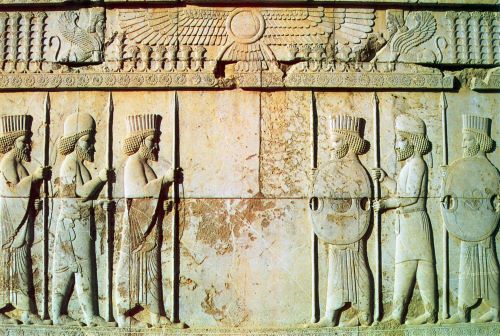

First, what is ‘Median dress’? If ‘Median’ is a proper ethnic term, the term designates whatever was properly and distinctively the dress of ethnic Medes. But, even if it is merely a word to describe menacing Persians, the fact that Herodotus has told us in 1.135 that Persians adopted Median dress invites the same conclusion. And that conclusion must be that the dress is the tunic-and-trousers outfit worn by most Iranians and some courtiers on the Apadana frieze and by all Persian soldiers in Greek representations, both visual and verbal.24

Are there any other relevant clothes that might have been seen at Marathon?

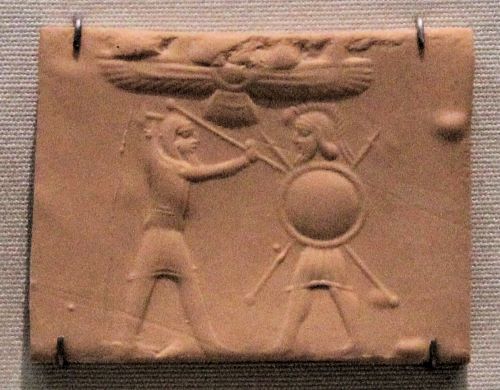

Persian iconography offers a form of Persian infantry not dressed in tunic and trousers, most famously represented by the Susa archers. It is easy to regard the long robes of such figures as parade-dress, but robed infantry appear in combat situations (and wielding spears) on a number of seals and in one of the Tatarlı wall paintings.25 Most of these (some twenty items) are crown-wearing royal figures and may have a symbolic quality; but the seal repertoire of combat scenes does contain six examples of non-royal robed infantry as against ten of non-royal trousered infantry,26 and that may be enough to give one pause about simply denying that Susa archers were ever used in battle. But the virtually total absence of any pertinent Near Eastern parallel for fighters wearing such encumbering dress,27 the possibility that all seal-images are prone to symbolism, and the single-mindedness with which Greek sources envisage nothing but trouser-wearers28 in the end leave one doubting that the Susa archer was much in evidence at Marathon.

What about non-Persian clothing? Who else was in the Persian army? Later sources speak of 500,000 or 600,000 troops or of an army of many myriads drawn from all of Asia;29 for a ship-borne force this is excessive fantasy even by Greek standards.30 Herodotus’ narrative avoids numbers (save for a historically useless 600 ships),31 but he has the Athenians at Plataea speak of fighting 46 nations at Marathon (9.27): and 46 is the number of peoples providing infantry units (with or without cavalry) in the Xerxes army list (7.61-83).32 Herodotus has done some arithmetic to construct rhetoric for his Athenian speakers – which exemplifies the resonances between the Marathon and Plataea narratives (already noted), but is perfectly useless for the historian.

The narrative locates Persians, Sacae, and some Greeks in the Marathon army. One of the commanders is described as a Mede, but Sekunda’s inference that Medes predominated in the rank-and-file is not obviously compelling.33 There are unclarities about the status and origin of the Greeks,34 but nothing suggests that Herodotus thought they played any role in the battle. The presence of Sacae is not necessarily a sign that the army was a composite entity drawn from many parts of the empire, since there is arguably a sense in which they are core imperial troops. Saka are among the few groups fully retained by Mardonius in 480/79 (Hdt. 8.113); they appear with Persians and Medes as on-ship marines in Xerxes’ war-fleet (7.96); and both Ctesias and Xenophon (in Cyropaedia) provide indirect evidence of their importance to the military establishment.35 Nor in general should we rush to think of Persian armies as heavily multi-ethnic composites, at least if we mean composites including significant numbers of non-Iranians. The historical record provides evidence on about 450 military events in the course of Achaemenid history. In all this material there are only four Persian armies for which we have descriptions that itemize significant numbers of ethnic contingents,36 and there are only five further (largely) unitemized assertions of multi-ethnicity or all-parts-of-empire origin.37 The evidence of such cases plus a few other instances of military activity by ethnically-defined units38 and the absence of any suggestion of generalized demilitarization of subject-peoples is probably enough to establish that Persian campaigns could draw on non-Iranian troops. A tablet from Sippar (CT 57.82) noting a payment of silver for ‘Šamaš-iddin and his horsemen who have come back from Egypt’ in the fourth year of Darius (518/17) provides welcome independent evidence that such troops might participate in a foreign venture – for we have reason to believe Darius did go to Egypt in his fourth year. But it is a real question how much this sort of thing happened. Just as Greek neglect of Susa archers argues they were comparatively rare in the real world of military practice, so visual reactions to the Persian invasions in general suggest that it was not variegation but an overwhelming uniformity of Iranian character that impressed. One exception, perhaps, is the appearance of black figures;39 and Herodotus 9.32 does place Ethiopians among Mardonius’ 479 forces. But the black figures are in quasi-Persian dress and never part of combat scenes; they are peripheral and Persified, which tends to confirm that Greek viewers were blind to the presence of significant numbers of distinctively non-Iranian troops. The stress on multi-ethnic diversity characteristic of Herodotus’ Army and Tribute List and (in almost entirely non-military mode) of the Achaemenid king’s own representations of imperial subjects at Persepolis and Naqš-i Rustam is not a reliable guide to actual battlefield practice.

The Marathon army came from the heartland: the situation resembles Mardonius in 492 or the second force sent against Inaros (Diod. 11.75), but differs from the campaign against Cyrene/Barca, the Naxos expedition, the land-forces deployed against the Ionian Revolt, the force of Mazaeus and Belesys fighting Tennes in the 340s, and the Granicus army, all of which represent use of satrapy-based forces certainly or possibly including non-Iranians.40 If the Marathon army contained anything that would not look Iranian, it might precisely be Mesopotamian – the only significant source of non-Iranian troops lying between Iran and Cilicia (where the army took ship).41 And, remarkably, an Assyrian-style helmet was part of the Marathon booty.

The upshot is that fighting Datis’ army at Marathon probably was primarily a matter of fighting men in ‘Median clothing’ – the men in ‘bags’ who epitomize the enemy in Aristophanes’ Wasps (1087). So, what reactions should this clothing have provoked?

Normal associations of Persian clothing were with luxury or effeminacy (Plutarch’s version of Marathon includes rich clothing in the booty recovered after the battle, Alexander historians contrasted the golden Persian army with the plain Macedonians, a trope that is already found in the Annals of Sennacherib,42 and Simonides or ‘Simonides’ spoke of the defeat of the khrusophoroi Mēdoi)43 or military inefficiency. Within the pages of Herodotus the reference to Mēdikos esthēs resonates with several other passages: Aristagoras encourages Spartans and Athenians with the inadequacy of Persian troops who fight with bows and short spears (5.49) and do not use shields or doru (5.97); at Thermopylae the Spartans provoke Xerxes’ ill-placed derision by exercising naked and combing their hair (while their arms and armour lie on the ground beside them), and the Persians are later at a disadvantage in battle because of their shorter spears (7.211); and at Plataea (9.62-3), Greek hoplites fight with inevitable success against the ‘unarmed’ (anhoplos) Persians.44 Aristagoras may at the time be cast to some degree as an unreliable witness – but his view is actually validated later, so it turns out that putative Greek inability to look upon Median clothing was rather misplaced. This may make the Athenians’ achievement in overcoming what was actually an irrational fear seem less splendid. But it also means that Herodotus may be claiming to provide evidence for a state of affairs that existed before 490 but did not exist by the time he was writing the Histories – a time when the barbaric and alien costume of the Iranians seemed scary, not absurd, self-indulgent, or inefficient.

Is there any other way we can get a handle on early reactions to Median clothing?

Herodotus incorporates something other than the later stereotype in Sandanis’ good advice to Croesus not to fight men in trousers who know nothing of luxury (1.71). The combination of the Lydians’ own reputation for both luxury and military excellence with their actual defeat by Cyrus certainly cast Median clothing here as a marker of startling military prowess. Nor was it only Lydians who displayed sartorial opulence: Ionian Greeks (under Lydian influence) affected dress which Cleidemus (323 F13) would in due course describe as recalling that of Persians, Syrians, and Carthaginians; and even Athenians of the Marathon generation were later seen as having followed this Ionian manner.45 Of course, playing with stereotypes like this is somewhat remote from the battlefield, but at any rate it does seem that Median dress need not always have been thought somehow effete or inadequate.

Nor did the earliest visual reflections of the Persian Wars obviously seek so to present it: pre-460 depictions of Greco-Persian fighting do not demonize the Persians,46 but they do not really demean them either, even if they are keen to show them as thoroughly defeated.47 Things only changed later (certainly by the time Herodotus was putatively reading his Histories to Athenian audiences), as painters started to domesticate and even parody Persian figures. But is there any handle we can get by going to pre-490 images? There are two possible categories of pre-490 Persian images in Attic ceramic art.

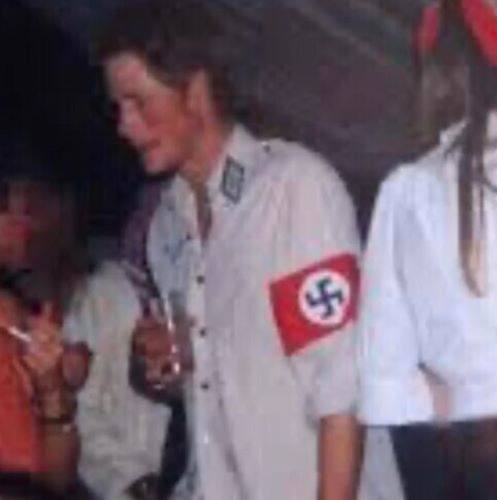

First, there are figures at symposia wearing what one naturally sees as Persian head-dress.48 The date range is variously stated, but they certainly began before 500. Explanations vary: either some Athenians did wear a foreign hat when drinking (and drinking perhaps from quasi-Persian vessels), this being merely a matter of upper-class fashion; or the hat symbolized the symposiarch. Either way, we seem to have a late-archaic version of that domestication of Median dress which is also found in the mid-fifth century. It is not the same species of domestication (though it may have more reality) and it only stretches to hat-wearing, but it is striking nonetheless. How frightened of a category of dress can one be if one is prepared to wear part of it at a party? For British readers that question may evoke Prince Harry’s 2005 appearance at a party wearing German desert uniform and a swastika armband – but that is a case which, mutatis mutandis, makes my point.

More numerous, and less easy to handle, are the many images of what have conventionally been called Scythians encountered from 570-470, but especially 530-490 and even more especially 520-500. In these latter periods the repertoire is dominated by scenes associating ‘Scythian’ archers with Greek hoplites, and doing so cooperatively not confrontationally. A recent very thorough treatment by Askold Ivantchik argues that:

- the crucial thing about the so-called Scythian archer is that he is an archer and of lower status; nothing in iconography or nomenclature makes him specifically Scythian;

- his dress is the dress appropriate to an archer, and the stimulus for ascribing such dress to archers was Medo-Persian, not Scythian – or, put another way, Anatolian not North Pontic. The great majority of items belong well after the arrival of Cyrus in western Asia Minor; the few earlier items (3% of the corpus, the earliest c. 570) reflect intermittent Lydo-Median clashes;

- the appearance of such archers on Attic vases is not due to there being actual oriental archers based in Athens but is simply an exercise in symbolic iconographic alterité.49

This last claim is not easy, and many may prefer to believe there were at least some ‘orientally’-dressed archers in sixth-century Athens. Peter Krentz has presumed as much recently,50 when arguing that a special example of the hoplite-plus-Scythian genre in which the archer carries a spear, not a bow, represents hoplites and archers running into battle at Marathon. For him those wearing oriental archer dress would actually be Athenians – a possibility also, I think, implicit in symbolic interpretations of hoplite-archer scenes, which presumably imagine the archers to be put in oriental costume for iconographic purposes, when in reality they were clad in some other fashion.

Either way, Ivantchik’s claim that the archer-dress is Medo-Persian makes Herodotus’ idea of Mēdikos esthēs being hard to look at without fear begin to seem rather awkward. If the images are primarily symbolic, they at least enshrine a notion of superiority – hoplite over oriental archer – that actually prefigures post-Persian Wars clichés and hardly seems consistent with fear of oriental garb as such. If, on the other hand, the images reveal that Athenians actually dressed thus, and did so for military purposes (not simply to go to parties), the inconsistency becomes even more pronounced. The jury is perhaps out on Ivantchik’s claims.51 But even if he is wrong we should perhaps conclude that the ‘Scythian’ vases were always something of a problem for 6.112: by any reckoning they show that a version of what is meant by Median dress was already well embedded in Athenian consciousness – and with demeaning associations. And, if he is right, it poses a big difficulty.

Conclusion

Discussion of the Median name revealed a certain tension between inferences from a lexical phenomenon and the absence of any upfront, consistent, and demonizing narrative about the arrival of Iranian military power in the Greek world. One could resolve that either by saying that post-Persian Wars accounts chose to play it cool (that it is not the classical manner to luxuriate in brutality and nastiness) – this would be, as one might say, a historiographical explanation – or perhaps by claiming that the lexical phenomenon is more about the Medes as alien invaders than necessarily as a source of fear. But the latter approach would take a lot of the sting out of the headline claim that even the name caused fear.

Discussion of Median clothing turns out also to produce a tension – and one that cannot perhaps so easily be resolved by saying we are comparing realities of 490 and before with narratives from a later date. One might try another approach and say that Athenians found it possible to distinguish the Median dress about which they had been psychologically robust for some time from the Median dress worn by people actually trying to do them harm: Herodotus does, after all, say ‘Median clothing and the people wearing it’.52 But that is perhaps just another way of saying that the headline reference to the clothing is misleading.53

I have no doubt that the Athenians at Marathon (and the Plataeans – let us not forget them) were decently afraid; the enemy was more numerous and no one could think of a precedent for Greek success in any comparable situation – for there was no precedent, though we might also say that there had not been many comparable situations: it is hard to know, for example, how many of the sieges of Greek cities were preceded by unsuccessful field-battles. It is understandable that Herodotus wanted to mark the watershed that Marathon certainly represented. But we may have to conclude that he overdid it just a little – an extra and distinctive small contribution by a foreigner to the alazoneia that, for Theopompus (115 F153), characterized the Athenian representation of Marathon.

Appendix

Most references to Medes in Egyptian texts actually come from post-Achaemenid era texts. One can distinguish the following categories: historical references in pseudo-prophetic texts and elsewhere to the Persian era as involving ‘Medes’;54 references to individuals who because of their fiscal standing are labelled variously (in demotic) as ‘Medes’55 or ‘Medes born in Egypt’56 or (in Greek) ‘Mede of the epigonē’;57 references to ‘soldiers’ that apparently use the demotic word for Mede to mean ‘soldier’;58 and a couple of items from the Inaros Epic cycle that are hard to classify in the absence of full publication – though in one case we have a narrative about Persians and Medes, so the latter term is presumably actually being used in something like a literal sense.59 Other examples of ‘Persians’ in post-Alexander texts include a substantial number of individuals labelled in Greek as Persai or Persai tēs epigonēs (a tax-category again), as well an allusion to the theft of religious objects by Persians during the Achaemenid era60 and an individual called Pyrrhias who is described in demotic as a Persian man: the date is early (287 BC), which may apparently tell against this being a tax-category usage.61

Apart from the retrospective references to the Achaemenid era foreign rulers as Medes, much of this material is hard to handle. There is still no clear explanation of why ‘Persian’ or ‘Mede’ defines a tax-category or why ‘Mede’ can come to mean ‘soldier’: it is at least possible that the two phenomena are not unconnected, though some have maintained that there had always been a native demotic word for ‘soldier’ that just happened to look like the word for ‘Mede’.62 It is notable that ‘Mede’ is very much rarer than ‘Persian’ in the tax-category group and is associated with people with Egyptian names. By contrast the normal demotic equivalent of Persēs tēs epigonēs is a phrase meaning ‘Greek born in Egypt’ – which coheres with the fact that most of the people described as Persai tēs epigonēs have Greek names (as does the one person described, in Greek, as Mēdos tēs epigonēs).63 There seems to be a sort of pattern here, but whether it helps to validate the conclusion that ‘Mede’ was, historically, a standard Egyptian word for ‘Persian’ remains a moot point.

If we look to the period before Alexander, the picture is mixed. The term ‘Persian’ is used of Persian officials in several of the hieroglyphic texts in Posener 1936 (nos. 24-31, 33-34), of a Persian weight-standard (TADAE I A6.2) and a type of sandal in Elephantine papyri (TADAE II B3.8), and in a highly fragmentary narrative from Saqqara which may also mention the fourth-century pharaoh Tachos and was conceivably dealing with his failed invasion of the Levant at the end of the 360s.64 On the other hand, we have two texts that can be taken to refer to individuals of specifically Median nationality (though one, from the reign of Achoris, may be rather uncertain),65 a Saqqara papyrus listing quantities of cereal for Carians, Arabs, men of Peqer, men of Daphne, and Medes (which again may be using the term strictly),66 another Saqqara papyrus (fifth century, but exThis letter admits of some further comment. It is a lengthy missive from one Osoroeris, complaining that he has been ousted as the representative of a lesonis-priest as a result of intrigues and expatiating on the question of how many loaves of bread should be made from an artabe of emmer; and the remark about the Medes is part of something Osoroeris’ addressee had written to him previously: ‘If the Medes do not kill us, you will discover the shamefulness of this behaviour by the priests (lit. ‘things of the priests’)’. The letter as atremely fragmentary) mentioning an army commander, pharaoh, and Medes,67 and a fourth-century letter from Elephantine containing the phrase ‘if the Medes do not kill us’.68

This letter admits of some further comment. It is a lengthy missive from one Osoroeris, complaining that he has been ousted as the representative of a lesonis-priest as a result of intrigues and expatiating on the question of how many loaves of bread should be made from an artabe of emmer; and the remark about the Medes is part of something Osoroeris’ addressee had written to him previously: ‘If the Medes do not kill us, you will discover the shamefulness of this behaviour by the priests (lit. ‘things of the priests’)’. The letter as a whole and the element relating to the Medes are thus both firmly embedded in the real and contemporary world, even if Osoroeris’ take on that real world may (for all we can tell) have elements of paranoia in it. Moreover, the letter is dated 26 Mechir in the eighteenth year of an unnamed king. It is highly tempting to identify the king as Nectanebo I or II, giving dates of 16 May 363 or 11 May 343. At both dates conflict with Persia was a live issue, and the possibility of death in Egypt at ‘Median’ hands may seem particularly fitting to the second date which, on conventional views, is precisely the time of Artaxerxes III’s reconquest of the country.69 Of course, other less high-profile locations are theoretically possible; if palaeography does not preclude it (and on that I have no clear information), we could look to the eighteenth year of Darius I (504), Xerxes (468), Artaxerxes I (447), or Darius II (406) and postulate some otherwise unknown internal trouble in Egypt or specifically in the Elephantine region – and the last of these dates is actually close to the era at which Egypt broke free from Persian rule for over six decades, so it could even be local trouble with larger ramifications. But, the important thing for now is that it would be straining plausibility to claim that ‘Medes’ in this letter simply refers to people who are ethnic Medes as distinct from other sorts of Iranian: Osoroeris’ correspondent was clearly using the term to designate the foreign power that ruled or threatened his country.

There is one final item to mention, not from Egypt but with an Egyptian connection – an inscription from Southern Arabia in which some traders commemorate a commercial journey to ‘Egypt, Transeuphratene and Assyria’ during which they had escaped safely from the dangers occasioned by a ‘revolt between the Medes and the Egyptians’, a phrase variously taken to refer to the rebellion of 404 or the reconquest of 343.70 The text is Arabian, but the terminology might reflect Egyptian usage.

See endnotes and bibliography at source.

Contribution (223-239) from Marathon – 2,500 Years, edited by Christopher Carey and Michael Edwards (University of London Press, 12.02.2013), Institute of Classical Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London, published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license.