He was a multi-skilled communicator who devoted his life to doggedly advocating for social change.

Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

“I was a writer and a newspaper man, and I

Jacob Riis, Quoted in the San Jose Mercury (March 11, 1911)

only yelled about the conditions which I saw.

My share in the work of the slums has been that.

I have not had a ten-thousandth part in the fight,

but I have been in it.”

Jacob A. Riis (1849–1914) was a journalist and social reformer who publicized the crises in housing, education, and poverty at the height of European immigration to New York City in the late nineteenth century. His career as a reformer was shaped by his innovative use of photographs of New York’s slums to substantiate his words and vividly expose the realities of squalid living and working conditions faced by the inhabitants. Harrowing images of tenements and alleyways where New York’s immigrant communities lived, combined with his evocative storytelling, were intended to engage and inform his audience and exhort them to act. Riis helped set in motion an activist legacy linking photojournalism with reform.

Riis is regarded as one of photography’s great innovators. Riis was well aware of the power of photographs but did not consider himself a photographer. This article repositions Riis as a multi-skilled communicator who devoted his life to writing articles and books and delivering lectures nationwide to spur social reform. It examines Riis as a writer, photographer, lecturer, advocate, and ally and provide visitors with an opportunity to understand the indelible mark Riis’s brand of social reform left on the United States at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century.

Biography

Overview

Jacob A. Riis (1849–1914) was born in Ribe, Denmark. He immigrated to America at age twenty with hopes of one day marrying his teenage love, Elisabeth Nielsen [Gjørtz]. Riis wandered through Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York, taking odd jobs as a laborer and salesman, before landing newspaper work in New York City in 1873. Financially established, Riis won Elisabeth’s hand; they married in Ribe in 1876 and settled in New York, where they raised five children. Riis recounted his remarkable life story in The Making of an American, his second national bestseller. In it, he chronicled his years as a homeless immigrant, his love story with his wife, and his enduring friendship with Theodore Roosevelt, who had become president of the United States only months before the book’s publication in 1901.

Making It as an American

Jacob Riis’s 1901 autobiography, The Making of an American regaled readers with accounts of the degrading experiences of his early years as a struggling immigrant through his astounding rise as a celebrated writer and confidant of the president of the United States—a story he used to promote his reform causes.

In his later years, Riis offered illustrated lantern slide lectures based, in part, on his autobiography. On this opening page of his lecture notes, Riis summarizes his Danish roots and refers to his precarious status upon arriving in America when he notes the ominous directive to “buy a revolver.”

Becoming American

Riis’s notes for his lecture titled “Making of an American” were drawn from his 1901 autobiography of the same name and his book The Battle with the Slum published in 1902. These notes offer a shorthand account of Riis’s entire career up to that point. Selected pages appear throughout the exhibition and serve as touchstones for Riis’s experience and observations. In these final two pages of the lecture notes, Riis recounts a personal epiphany he experienced while ill during a visit to Denmark in 1900, when he realized he had truly taken on an “American identity.”

Pocket Diary and Telegram

Between September 1871 and August 1875, Riis kept a pocket diary, first in Danish and then in English. Two of his three diaries survive; they recount a period of struggle and painful self-doubt. Riis wrote his final entry on August 16, 1875, after asking for Elisabeth’s hand in marriage. The happy pair married in Ribe, Denmark, in 1876 and raised a family in New York. They remained married for twenty-nine years, until Elisabeth’s untimely death on May 18, 1905. In this May 7, 1905, telegram, Riis urges their son John to hurry home to see his failing mother. Riis was heartbroken at her passing.

Family Life in Richmond Hill

In 1884, Riis purchased a plot of land in Richmond Hill—today part of Queens, New York, and home to many South Asian, South American, and Caribbean immigrants. In 1886, Riis moved his family into a new house there. In the image above, probably taken in their yard, Riis’s wife Elisabeth is seated and surrounded by their five children.

Reporter

Overview

For twenty-three years, Riis worked for the New York Tribune and the Evening Sun from an office at 301 Mulberry Street across from police headquarters in the heart of the Lower East Side. Six of those years were spent working nights on the police beat, witnessing criminality and deprivation and gaining an intricate knowledge of street life. With his Danish accent and crusader views, Riis was an outsider among his fellow journalists. He proved his mettle, however, and became the “boss reporter.” Writing in a sentimental yet critical style similar to Charles Dickens, he was unyielding in his depiction of the vices, travails, and efforts of the urban poor. From the start of his work in journalism, he used the personal stories of the slum dwellers he met to paint a vivid picture of what it was like to inhabit the city’s tenement neighborhoods.

Jacob Riis, Reporter

The photograph above depicts Riis (back corner) and his partner, Amos Ensign (seated at the desk) waiting for breaking news in their New York Tribune office on Mulberry Street across from police headquarters. The abundance of images tacked to the wall above their desk attests to the important interplay between policing and news reporting in the 1880s. It could be grueling work.

In his autobiographical lecture notes Riis wrote: “‘My first assignment as a Reporter’—Stayed 25 years—not willingly—after one year wanted to get out—was made to stay . . . Compelled there to see the seamy side of everything. I looked behind the gore and the grime of it for the cause.”

Keeping Account

Jacob Riis was known as an “easy mark,” willing to help anyone with a hard luck story. He tried to save money by keeping annual account books. He successfully cobbled together income to support his growing family not just as a reporter in the grit of city streets but by crafting freelance articles and talks that would appeal to middle-class audiences. On the first page of this 1895 ledger, Riis wrote:

“This account of receipts and expenses was opened on January 1st 1895, so that I might find out where my money goes, and how much of it I get anyhow. We shall see.”

The book is open to Riis’s various sources of income including salary, payments, and lecture fees—tallied from April through the end of October and totaling $3558.60 for the entire year. Riis referred to the 1890s as “golden years.”

Criminal Conditions

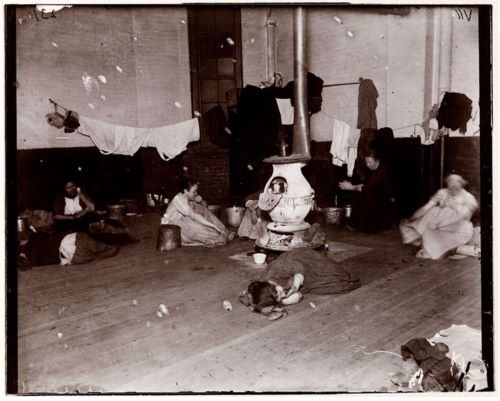

In 1891 and 1892, Riis took photographs to illustrate his newspaper accounts. In 1892 and 1893, in a series of four articles and his touring lantern slide lecture, Riis decried the appalling conditions of New York’s police lodging houses, which served as de facto homeless shelters.

Riis discussed these photographs of the West 47th Street lodging rooms in an article for the New York Tribune, which reproduced the images as single-line wood engravings. In the men’s lodging room photograph it is difficult to distinguish between piles of lumber and sleeping bodies. And in the women’s lodging room image a young woman at the center of the frame cries, hiding her face from the camera.

Riis sought to capture the indignity of the lodging houses, but the Tribune derisively captioned the men’s lodging rooms as “Rubbish, Some of It Human.”

Police Lodging Houses

Riis’s news accounts cast the police station lodging houses as breeding grounds for crime and public health crises, such as outbreaks of typhus. This article, which appeared in the Christian Union on January 14, 1893, again reproduces the men’s lodging room, this time in a tonally flat halftone. The article is from a scrapbook that Riis assembled to chronicle his career as a journalist and lecturer. Riis’s crusade was based not just on combating communicable disease, but observations of the vulnerability of young people to physical harm or recruitment by seasoned criminals and on his own bitter experiences as a newly arrived immigrant, homeless and unable to afford rent. In 1896, the lodging houses were finally closed with the support of then Police Commissioner Theodore Roosevelt.

Photographer

Overview

Jacob A. Riis’s success as an agent of reform derived not only from his passionate advocacy in print and on the lecture circuit but from his innovative use of the media of his time. He was the first reformer to recognize the potential in new methods of low-light flash photography. He used photographs of squalid conditions in the poorest parts of New York City to convince middle-class audiences of the need for action. Describing himself as a “photographer after a fashion,” he first guided avid amateur photographers willing to test new flash techniques to take nighttime pictures in the slums. Soon Riis began taking photos on his own, letting commercial firms do the darkroom work. The 100 images he assembled for his “Other Half” lecture slides were powerful persuaders, but the impact of those pictures was diminished in print because 1890s printing technology dictated that images be reproduced as crude wood engravings or tonally flat halftones.

The Tramp

Riis’s earliest photographs were taken in association with amateurs Richard Hoe Lawrence and Dr. Henry G. Piffard. Riis’s lecture notes describe the first flashlight photographs taken by the trio, who also posed this “tramp” in a “yard” only a block from Riis’s Mulberry Street newspaper office. Riis had little sympathy for chronically unemployed men, whom he characterized as content to live off the charity of others.

He described the “Tramp” photo shoot this way:

“On one of my visits to ‘the Bend’ I came across this fellow sitting . . . and he struck me as being such a typical tramp that I asked him to sit still for a minute and I would give him ten cents. That was probably the first and only ten cents that man had earned by honest labor in the course of his life and that was by sitting down at which he was an undoubted expert.”

Making an Impact with Images

Riis’s earliest lantern slide shows were modeled on the “slum tour” genre that he honed into a popular lecture and his bestselling book How the Other Half Lives. In his later years, Riis offered lectures based on two of his books, The Making of an American (1901) and The Battle with the Slum (1902). His standard lecture fee was $150, and the venue was required to supply a magic lantern and a technician to operate it. Riis arrived with his box of lantern slides and rough notes jotted in pencil on whatever paper was handy.

Riis’s Collection of Photographs

After 1895, Riis took very few photographs of his own. He may have been too busy; in this period, he was devoting much more time to politics and writing for national magazines. The decline in his photographic output also coincided with the rise of halftone reproduction in magazines, which spawned a growing number of professional photographers working in the reform field. When preparing A Ten Years’ War (1900) and The Battle with the Slum (1902), Riis was able to acquire professional photographs, from which he ordered copy negatives, copy prints, and lantern slides. The sudden increase in the size of his collection led him to number his negatives and create this inventory.

Mulberry Street Yard

The portrait of the tramp, taken by Riis, Lawrence, and Piffard, was among the group of images that Riis was invited to show at the monthly lantern slide meeting of the Society of Amateur Photographers of New York in January 1888.

Before 1898, the year that marked the demolition of this yard, Riis returned alone to the same spot at the junction of Jersey and Mulberry Streets to photograph the new occupants of the yard. This later photograph was published in Riis’s 1902 book The Battle with the Slum with the caption: “It costs a Dollar a Month to sleep in these sheds.”

Writer

Overview

Jacob Riis wrote his first (and now enduringly famous) book, How the Other Half Lives (1890) late at night “while the house slept.” He recalled: “It was my habit to light the lamps in all the rooms of the lower story and roam through them with my pipe, for I do most of my writing on my feet.” The book was a bestseller. Riis continued to pursue his activism through writing. His long stint as a police reporter, first with the New York Tribune and then the New York Evening Sun, ended in 1901, but Riis continued to produce a stream of freelance articles for newspapers and literary magazines like Scribner’s, the Century, and the Churchman. He also published nearly a dozen influential books involving urban reform, including The Children of the Poor (1892), A Ten Years’ War (1900), The Making of an American (1901), and The Battle with the Slum (1902).

Shedding Light in Dark Places

Wood engravings of Riis’s photographs published in How the Other Half Lives maximized the impact of his powerful text. Notorious lodging houses in New York charged customers seven cents or more a night for a bed, or five cents to sleep crowded illegally on the floor. Riis accompanied the sanitary police on a raid of one such lodging house and took this photograph of a room thirteen feet square, in which he observed, “slept twelve men and women, two or three in bunks set in a sort of alcove, the rest on the floor.” Riis and his colleagues took three photographs of an opium joint in Chinatown.

This photograph shows a man dozing on a platform with his smoking implements nearby and an attendant looking on. Riis explained that “these hapless victims of a passion once acquired, demands the sacrifice of every instinct of decency to its insatiable desire.”

“How the Other Half Lives”

Riis received his first break when two Scribner’s Magazine editors attended his “Other Half” lecture and invited him to publish it as an article. The resulting piece featured twenty wood engravings based on Riis’s photographs and was the highlight of the magazine’s 1889 Christmas issue.

As this receipt shows, Riis was paid $150 for the article, equivalent to a month’s newspaper salary.

Words on the Page

Riis dreamed of converting his “Other Half” lecture into a book: he drafted a title page, had it printed, and submitted it to the Library of Congress for copyright in 1888. He got his lucky break from Scribner’s. A year after the illustrated article appeared in Scribner’s Magazine (December 1889), Scribner’s published Riis’s work in book form, How the Other Half Lives, Studies Among the Tenements of New York (1890).

One Riis admirer, the poet James Russell Lowell, permitted Riis to use a portion of his poem “A Parable” as the epigraph. The poem tells of Christ chastising those who honor him with displays of wealth while neglecting the poor.

Writing the Book

How the Other Half Lives has long been recognized as a classic in the “muckraking” reform tradition. Riis reworked his lecture notes and various stories he wrote as a journalist into the book. He incorporated vignettes about individuals written from observation or based on interviews with people he met or photographed. He also collaborated closely with Dr. Roger S. Tracy, Registrar of Records in the Health Department, and other authorities to understand the statistical and sociological data that underlay the conditions he saw manifested in the streets and tenement houses.

Reformer

Overview

Based on his own experiences as an immigrant and his knowledge of the slums as a police reporter, Riis advocated for practical solutions to a wide array of social problems. Through lectures, newspaper and magazine articles, and books like How the Other Half Lives (1890) and The Children of the Poor (1892), Riis worked tirelessly to influence public opinion. He met with a hostile reception from New York City’s powerful political machine, Tammany Hall, whose leaders saw well-meaning, middle-class reformers as a threat to their influence. But in 1894, an anti-Tammany reform candidate, William L. Strong, won the mayor’s office and instituted a period of “good government” policies. Among Strong’s appointments was a young Theodore Roosevelt as police commissioner. Roosevelt befriended Riis and supported his causes, as Riis advocated for the destruction of the worst of the old tenements, the construction of parks, education for children, and the closing of the dangerous police station lodging houses.

The Children of the Poor

Jacob Riis was very concerned about the impact of poverty on the young, which was a persistent theme both in his writing and lectures. For the sequel to How the Other Half Lives, Riis focused on the plight of immigrant children and efforts to aid them. Working with a friend from the Health Department, Riis filled The Children of the Poor (1892) with statistical information about public health, education, and crime. He argued that teaching immigrant children about American democracy would help to make them productive citizens.

For this project, Riis radically changed his approach to his subjects. He established a rapport with the children who posed for him before taking their photograph and included their stories in his text.

“I Scrubs”

From 1854 to 1874, the Children’s Aid Society in New York City established twenty-one industrial schools, which offered academic and technical classes, medical care, and recreational programs to children who, because of the conditions of their impoverishment, could not attend public school.

Riis met Katie at the West 52nd Street Industrial School, where he interviewed her and took her portrait. Riis featured her story, as well as those of other children, in his 1892 Scribner’s article illustrated with wood engravings made from Riis’s photographs. Later that year Riis turned his “The Children of the Poor” article into a book of the same name:

This picture shows what a sober, patient, sturdy little thing she was, with that dull life wearing on her day by day. . . . She got right up when asked and stood for her picture without a question and without a smile. “What kind of work do you do?” I asked, thinking to interest her while I made ready. “I scrubs,” she replied, promptly, and her look guaranteed that what she scrubbed came out clean.

3 a.m. in the Sun Office

In a chapter on “The Homeless and Outcast,” in The Children of the Poor, Riis emphasized that most homeless boys were not orphans:

The great mass. . . . of newsboys who cry their “extrees” in the street by day . . . are children with homes who contribute to their family’s earnings, and sleep out, if they do, either because they have not sold their papers or gambled away their money at “craps” and are afraid to go home . . . . In winter the boys curl themselves up on the steam-pipes in the newspaper offices that open their doors at midnight on secret purpose to let them in.

Riis worked for the New York Sun in the 1890s and may have known these boys. Unlike the “Street Arabs” who feigned sleeping to pose for How the Other Half Lives, these boys seem genuinely asleep.

Industrial Schools

The students at an industrial school were asked to share with their parents a handout—“a Voter’s A, B, C, in large type, easy to read”—about an upcoming vote at the school. Riis inserted the handout in his manuscript for his book The Children of the Poor. He believed that children could teach their immigrant parents about the fundamentals of citizenship and that introducing immigrant youth to the principles of American democracy would go a long way toward making them proud citizens.

At the Beach Street Industrial School, an administrator asked the students to vote on whether the school day should begin with a salute to the American flag. In The Children of the Poor (open to the illustration of three girls who were selected as election inspectors), Riis observed that “the tremendous show of dignity with which they took their seats at the poll was most impressive.”

Lecturer

Overview

Jacob Riis traveled the United States several months out of the year—and, on occasion, abroad—delivering rousing illustrated lantern slide lectures. His presentations drew crowds that ranged in size from less than one hundred to several thousand. Riis had gained wide recognition for his early “Other Half” lecture in 1888–1889. In later years, he offered lectures on his second bestselling book, the autobiographical, The Making of an American (1901) and his 1902 book The Battle with the Slum. He found audiences in churches, charitable organizations, and schools receptive to his crusading message of social change.

His fame allowed him to retire as a police reporter in 1901 and rely on lecturing as his primary source of income. For several months out of the year, he crisscrossed the country, even after a serious heart attack in 1900 and against doctor’s orders. Riis’s 1901 autobiography The Making of an American, in which he regaled readers with accounts of the degrading experiences of his early years as a struggling immigrant, consolidated his status as a celebrity and resonated with audiences across the country. A newspaper account of Riis’s 1911 lecture in San Jose, California, noted: “Simply as the story was told, it held the listeners wrapt. ‘If,’ said [Riis] in closing, ‘the story of one plain immigrant lad helps you to look with kind eyes on one little unfortunate lad I shall think my words well spoken.’”

On the Lecture Circuit

Riis filled a scrapbook with letters, reports, and reviews of his first lecture, “How the Other Half Lives and Dies in New York.” On the title page, he wrote: Press Comments on the lecture / “The Other Half” / how it lives and dies in New York. / illustrated with 100 photographic views / by Jacob A. Riis / Delivered for the first time / January 25th 1888 / before the Amateur Photographers’ Association / at 122 West 36th St / New York. Riis was a strong supporter of the King’s Daughters’ Tenement House Committee, a Lower East Side social service organization.

In 1890, he lectured to raise funds for a permanent headquarters, and 48 Henry Street was acquired in 1892. Advertisements promised groups who hosted Riis’s lectures that they would be “both entertained and instructed.” In 1901, the organization was renamed the Jacob A. Riis Neighborhood Settlement House. The agency relocated to Queens in 1952 and maintains a lasting legacy of advocacy, education, and programs for the poor.

Friendship with Theodore Roosevelt

By the time President Theodore Roosevelt’s 1905 letter reached the address in Santa Barbara, California, where Riis had taken ill while on a lecture tour, Riis had already moved on to the southern portion of his itinerary. Roosevelt was affectionate with his friend “Jake” and generous in his hospitality. Here he writes on White House stationery to express concern for Riis’s welfare and to invite Riis and family members to attend his inauguration in Washington. Roosevelt rose to the executive office from the vice presidency after the assassination of William McKinley in 1901 and began his first full term as an elected president on March 4, 1905.

A Transcript of a “Story in Pictures”

This pamphlet contains the only printed version of Riis’s lecture “How the Other Half Lives.” The lecture was delivered at the First Congregational Church in Washington, D.C., on November 9, 1891. In parentheses, the printed transcript indicates the pictures that were shown and the places where the audience laughed or applauded. In the margin of the first page, Riis wrote:

“This is the only stenographic report taken of my lecture. It is not an extra good one, or rather it is not a report of an extra good lecture, . . . . As I speak without notes, from memory and to the pictures, the result is according to how I feel. The occasion was a success, however, from the standpoint of the audience, which was very large.”

From the Road

Jacob Riis kept in close contact with family and friends as he traveled the country, particularly his wife and daughter Kate. The Library’s Riis collection includes letters detailing his observations and picture postcards showing places he visited. For several months out of the year, Riis crisscrossed the country, often despite poor health. Riis’s twelve appointment books on view chronicle the grueling schedule of public lectures he maintained from 1902 until his death in 1914. The open book reveals that despite the likelihood of harsh weather, Riis scheduled lectures from Memphis, Tennessee, to Columbia, Missouri, between February 7 and February 20, 1909.

Picture postcards sent by Riis to family members from the states of Washington, New Jersey, Minnesota, California, and New Hampshire; the District of Columbia; and the countries of Belgium, Algeria, Denmark, Germany, and Austria, between 1902 and 1908.

Lantern Slide, Mulberry Street

Beginning in 1900, Riis acquired numerous photographs to illustrate his books, articles, and lectures. He numbered the negatives and organized them into an inventory including this famous image of Mulberry Street marketed as a hand-colored lantern slide and as a postcard by the Detroit Publishing Company. The image has come to exemplify the Lower East Side at the turn of the twentieth century with the street teaming with people, and the crowded tenements seemingly ready to burst out of the picture frame.

Ally

Overview

Jacob Riis’s career-long “battle with the slum” was aided through acquaintances and friendships with political and affluent allies—the most powerful being Theodore Roosevelt. Their deep friendship began in 1895 when then Police Commissioner Roosevelt sought out Riis in his newspaper office across from police headquarters on Mulberry Street. Riis took the commissioner on a series of nighttime forays into the slums and used the relationship to make recommendations for reform of the police and health departments, many of which Roosevelt embraced. Over time their bond strengthened, even after Roosevelt left the city to climb the rungs from a state to a national political career. The two men supported each other publicly—artfully using the media to enhance their mutual reputations.

Theodore Roosevelt and Jacob Riis remained close friends during Roosevelt’s climb to the White House. In March 1901, Roosevelt penned an article for McClure’s Magazine, dubbing Riis “the most useful citizen of New York.” He observed that

“There are certain qualities a reformer must have if he is to be a real reformer. . . . He must possess high courage, disinterested desire to do good, and sane, wholesome common sense. These qualities he must have; and it is further much to his benefit if he also possesses a sound sense of humor. All four traits are possessed by Jacob Riis.”

The admiration was mutual. Riis’s 1904 campaign biography Theodore Roosevelt the Citizen, extolled the president’s virtues:

“it was when that same strong will, that honest endeavor, to see right and justice done to his poorer brothers—it was when they joined in the battle with the slum that all my dreams came true, all my ideals became real.”

A Ten Years’ War

Riis reviewed his decade of reform, which began in 1890, in his book A Ten Years’ War (1900). He called the two years (1895–1897) he worked actively with Roosevelt crusading against police corruption and housing conditions in New York City “the happiest by far” of his time as a reformer.

When Roosevelt became governor of New York (January 1899 to January 1901), Riis encouraged him to improve the standards of state factory inspection.

Roosevelt’s letters to Riis mention social worker James Bronson Reynolds and child-labor reform advocate and seasoned factory inspector Florence Kelley, both important allies in improving factory inspection at the state and national levels.

A Hospital for Children

In the early 1900s, tuberculosis was the second leading cause of death in New York City, disproportionately affecting the urban poor. For five years, Riis incessantly lobbied to build a seaside hospital for tubercular children on land in Far Rockaway, Queens, New York. Louise Carnegie, wife of New York industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie, read Riis’s 1906 article about the plight of these ill children and his campaign to raise funds and sent Riis a warm note and a $10,000 check. The project, however, met continued resistance from private developers and politicians.

After five years without progress, Andrew Carnegie wrote Riis this brusque note:

“Mrs. Carnegie . . . has made a contribution and before more is askt [sic] we should hav [sic] a statement of the present conditions of the institution, especially a list of subscribers and amounts given so far.”

Though Riis’s initial efforts for a facility were unsuccessful, New York’s first public hospital for treatment of tuberculosis opened on Staten Island in 1913.

Booker T. Washington and Tuskegee Institute

In 1901, the year that both Jacob Riis and Booker T. Washington published important autobiographies (The Making of an American and Up From Slavery), Washington suggested that Riis accompany Vice President Theodore Roosevelt on a trip South to visit Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. The trip was tentatively set for November but was cancelled when President William McKinley was assassinated in September, unexpectedly launching Roosevelt into the presidency. The trio remained in touch.

Shortly after taking office, Roosevelt famously welcomed the African American leader to dinner at the White House. Riis guided Washington on a tour of the Lower East Side in 1904, and finally visited Tuskegee himself in 1905, writing home enthusiastically to his wife about the experience.

Friends in High Places

Riis’s longstanding friendship with Roosevelt placed the reformer among those in the president’s inner circle. The magazine of political satire and humor, Puck, parodied the reaction of Roosevelt’s allies, cabinet members, and White House guests to the end of his presidency. In the image above, President Theodore Roosevelt stands at the center with his successor William H. Taft and a gathering of his “officers.” Riis appears as a colonial army officer with a handkerchief to his eyes (second from the left), while Attorney General Charles J. Bonaparte is Napoleon, Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute founder Booker T. Washington stands in the doorway, and naturalist John Burroughs towers in frontier costume. Everyone, except Roosevelt, is crying.

Riis and Reform

New York City

When Jacob Riis published How the Other Half Lives in 1890, the U.S. Census Bureau ranked New York as the most densely populated city in the United States—1.5 million inhabitants. Riis claimed that per square mile, it was one of the most densely populated places on the planet. The city is pictured in this large-scale panoramic map, a popular cartographic form used to depict U.S. and Canadian cities and towns during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Known also as bird’s-eye views or perspective maps, panoramic maps render places as if viewed from above at an oblique angle. Although not generally drawn to scale, they show street patterns, individual buildings, and major landscape features in perspective. This map helps visualize the extreme density, particularly in the Lower East and West Sides of Manhattan, and Jacob Riis’s lifelong concern with ameliorating the lot of those that lived in its crowded slums.

Housing

As governor of New York, Riis’s friend Theodore Roosevelt appointed a Tenement House Commission, which led in 1901 to the creation of the Tenement House Department, headed by another Riis friend, Robert de Forest of the Charity Organization Society. Riis and this circle of municipal citizen-reformers, which included social welfare activists Josephine Shaw Lowell and Lillian Wald, worked to gather statistical evidence and raise public awareness. They advocated for new housing designs to ease crowding and improve fire safety, sanitation, and access to air and light. Riis described the evolution of tenement house reform as a forty-year effort, which included demolishing the Five Points and Mulberry Bend neighborhoods, initiating new construction, cleaning the streets, creating parks and playgrounds, tearing down rear tenements, and cutting more than 40,000 windows through interior walls to let in light.

Flat in Hell’s Kitchen on the West Side

Riis wrote in his 1889 article for Scribner’s Magazine, “How the Other Half Lives:” “Not that all the tenements above Fourteenth Street are good, or even better than those we have seen. There is Hell’s Kitchen and Murderers’ Row in the region of West-side slaughter-houses and three-cent whiskey. . . . ” The couple in this photograph taken by Riis lived on New York City’s West 38th Street in a barracks that covered an entire city block and lacked interior windows, ventilation, and indoor plumbing.

Fire Insurance Map

During the first half of the nineteenth century, most fire insurance companies were small and based in a single city. The underwriters could personally examine properties they were about to insure. As insurance companies became larger and expanded their coverage to numerous cities, a mapping industry developed to support the greater need. Insurance maps provided block-by-block inventories of existing buildings–such as the map of the New York City’s Hell’s Kitchen, home to a large population of Irish immigrants in Riis’s time.

The outline or footprint of each building is indicated, and the buildings are color coded to show the construction material: pink for brick, yellow for wood, and green indicated “specially hazardous risks” for insurers.

Public Health

Disease, sanitation, garbage and hygiene issues were constant concerns in crowded impoverished tenement districts, where vital statistics were alarming. Jacob Riis wrote frequently to urge measures to protect public health and to alert wealthy residents of the city to slum conditions that put everyone at risk. Poor water quality, filth, vermin, and compromised living conditions meant typhus and cholera outbreaks were common, as were high rates of child mortality and tuberculosis. Rag pickers and petty thieves made city dumps their homes, while unemployed “tramps” lived in shack housing in back alleyways. The Tenement House Committee of 1894 (known as the “Gilder Committee) called rear tenements “infant slaughter-houses,” where as many as one in five babies died. Riis collaborated with health and hygiene department officials to compile and report sources of disease and seek remedies to improve public health.

Children of the Dump

In the winter of 1892, Riis visited eleven of the city’s sixteen riverside dumps to investigate the enforcement of two public health laws: one required that old rags be washed before resale, and the other forbade rag pickers from living in the dumps.

He learned that neither law was enforced. Riis interviewed the rag pickers and took seven photographs, five of which were reproduced as line engravings in the Evening Sun. Riis saw women and children working and living in the dumps. He wrote:

“I found boys who ought to have been at school, picking bones and sorting rags. They said that they slept there, and as the men did, why should they not? It was their home. They were children of the dump, literally.”

Public Space

As older dense buildings gave way to new tenement design, Riis advocated for open-air parks for children, who previously had nowhere but the streets or the dark hallways and cramped back spaces of tenements to play. Riis helped raise support for small public parks and thought that every public school should have a playground. He believed in the right of boys and girls to play as part of healthy early child development, and as an outlet for energies that could instead be turned to lives of vice or crime. One of Jacob Riis’s triumphs as a reformer was the creation of Mulberry Bend Park where crime-ridden housing had once been. Riis believed in the benefits of exposure to nature and also supported the idea of excursions for city kids to farms and meadows in the countryside.

Establishing Parks and Playgrounds

Riis photographed a privately funded, experimental playground at West 28th Street between 11th and 12th Avenues, the block pictured in the map above, where equipment was installed, and a janitor and two teachers were hired to watch the children. Riis described the park:

“It was not exactly an attractive place. . . . But the children thought it lovely, and lovely it was for Poverty Gap, if not for Fifth Avenue.”

Riis helped establish several small public parks in tenement neighborhoods including a park on Rivington Street.

This petition, signed by 300 school girls “to make the corporation yard at the foot of Rivington St. into a public play-ground,” succeeded. Hamilton Fish Park opened in 1900.

Crime

As a young new immigrant, alone, homeless, and struggling to find work—with only a stray dog as a companion on the street—Jacob Riis was the victim of crime at a police lodging house. A locket bearing an image of his beloved Elisabeth was stolen from him in his sleep. Reporting the crime, he was thrown from the premises by a disbelieving policeman, who clubbed his dog to death when it snarled in his defense. Riis never forgot either the theft or the brutality, and his crusade against conditions in police lodging houses became his vendetta. Claiming the true crime was the lack of action on the part of municipal authorities to institute reform, Riis campaigned for the establishment of city-run lodging houses as an alternative, both to alleviate public menace and provide decent habitation for men and women in crisis.

Bandits’ Roost

Bandits’ Roost was an alley on Mulberry Street on New York’s Lower East Side, where Italian immigrants paid excessive rent to live in “rear tenements,” ramshackle structures that were added onto old houses. Riis, working with amateur photographers Richard Hoe Lawrence and Henry G. Piffard, took this photograph with a stereoscopic camera, which produced two side-by-side images: on the left is a woman with two small children; on the right, young “toughs” look warily at the camera.

Riis led a ten-year crusade to clean up the area in which this photograph was taken; called “Mulberry Bend,” it was notorious as a haven for gangs and criminal activity.

Labor

Jacob Riis worried about sweatshop labor taking place within tenement apartments and in small factory locations in the Lower East Side. Whole families, including children, as well as hired help, would often be involved in various levels of piecework. Garment making (cutting, sewing, tailoring, pressing), cigar making, millinery, and artificial flower assembly, were among the forms of production at which immigrant laborers worked in crowded hot conditions inside residences and were paid by the “piece” or the lot. Sweatshop labor meant health risks, including high rates of consumption and shortened life spans. Riis was dismayed about child labor in particular—in homes and in factories. Adolescent girls tended younger siblings while parents worked, or took on heavy domestic jobs like laundry and scrubbing. Out in the streets, newsboys roamed at night and vice beckoned boys and girls alike. Riis lamented that many of these little children appeared old before their time from taking on adult forms of labor.

Piece Work—Cigar-Making

Riis devoted a chapter of How the Other Half Lives to “The Bohemians—Tenement-House Cigar Making.” Riis described these Eastern European immigrants as working seventeen-hour days, seven days a week, inside their apartments rank with toxic fumes, making pennies an hour by stripping and drying piles of tobacco leaves and rolling finished products. In the Riis photograph, the parents work at the cigar mold and their oldest child, at the center of the frame, prepares the tobacco leaves for rolling.

Fire Insurance Map

During the first half of the nineteenth century, most fire insurance companies were small and based in a single city. The underwriters could personally examine properties they were about to insure. As insurance companies became larger and expanded their coverage to numerous cities, a mapping industry developed to support the greater need. Insurance maps provided block-by-block inventories of existing buildings—such as the map above of an area east of the Bowery where there was a dense concentration of Jewish tenement sweatshops. The outline or footprint of each building is indicated, and the buildings are color coded to show the construction material: pink for brick, yellow for wood, and green indicated “specially hazardous risks” for insurers.

Education

Jacob Riis honored education, especially for children, as a way up and out of slum life. The son of a schoolmaster, Riis had been a rebellious student; nevertheless, he loved to read as a child. He believed that education was not just a pathway to better employment and a more fulfilled and informed life, it made good naturalized citizens. Riis was a strong supporter of industrial schools, which imparted practical job-related skills and taught civics lessons to children whose families originated from many nations. Though work was almost always a necessity, some first-generation immigrants recognized the better chances that literacy in English could bring to their children, and supported their sons and daughters in their desire to learn to read and write. Riis also worked with the New York Kindergarten Association and settlement house workers to promote early child education.

Educating the Young

Pietro worked as a bootblack before he was hit by a streetcar and maimed. Riis made two photographs of the boy at his home on Jersey Street, where he was learning to write English, “in the hope of his doing something somewhere at sometime to make up for what he had lost.” In the photograph above, the thirteen-year-old Pietro is shown with his mother and young sibling.

Riis believed that introducing immigrant children to the principles of American democracy would go a long way toward making them proud citizens. The administrator of the Beach Street Industrial School on the Lower East Side of New York asked the students to vote on whether the school day should begin with a salute to the American flag. Riis’s photograph shows the students casting their ballots, monitored by the student election inspectors.

Homelessness

Jacob Riis, himself once homeless as a young man new to the United States, wrote sympathetic vignettes about those who fell on hard times and became homeless—often due to the loss of a job or an injury or, because they were evicted from their tenement homes when they could not afford escalating rents. Riis lamented the indifference of employers and the greed of landlords. But he reserved particular venom for those who begged for a living or who did not actively seek work, a category of homeless he referred to as “tramps.” His campaign against police lodging houses, which acted as nightly homeless shelters, was due to their poor conditions and their role in the spread of crime and disease, but also because they perpetuated this form of homelessness. With the help of then Police Commissioner Theodore Roosevelt, the police station lodging houses were closed in 1896, with the intent that those displaced were to be served by improved charitable and civic services.

Eldridge Street Station

In 1892 and 1893, Riis took photographs of the deplorable conditions of the police lodging houses, which served as the city’s homeless shelters. These images illustrated his articles and a lecture at the Academy of Medicine in February 1893—a lecture Riis gave to garner support for closing the houses and replacing them with a municipal wayfarer’s lodge.

The police station lodging rooms at 87/89 Eldridge Street, located on the lower right portion of the map above, sheltered only women. When a sick man asked to stay for the night, he was placed in an empty room and laid down on the bare plank floor. It was soon discovered that he had typhus. Riis wrote:

It was a piece of good luck that it was this [station] the typhus lodger found his way, or there is no telling where the trail of contagion he would have started might have ended.

Immigration

Ellis Island served as the gateway for more than twelve million immigrants from many nations between its opening as the U.S. immigration inspection station at the port of New York in 1892 to its closing in the 1950s. When Riis emigrated from Denmark in 1870 to seek “an honest dollar,” the German, Irish, and Chinese immigration of the mid-century was ebbing. Most Scandinavian immigrants headed to farmland and cities in the West and Midwest. As Riis gained fame in his career—between 1890 and his death in 1914—a “third” or “new” wave of immigrants arrived in New York. Of many nationalities and faiths, they came primarily from Russia, Italy, and Eastern Europe. When featuring New York’s immigrant groups and their neighborhoods in his articles and bestselling books, Riis expressed personal religious and ethnic prejudices, but he steadfastly championed immigrants he perceived to be of good character and drive.

In Jersey Street

An Italian family lived in this one-room, windowless home on Jersey Street, a few blocks from Riis’s Mulberry Street office. Jersey Street in the map above is sandwiched between Prince and East Houston Streets and is crammed with the back-to-back tenements that Riis railed against. In Riis’s photograph the family’s possessions and furnishings, which includes a rolled mattress, barrel, and piles of clothes; a dustpan, a basin, a wooden pallet that may have served as a bed, and a cast iron stove and various containers, fill the frame. Riis commented on the Italian custom of swaddling:

“You can see how they wrap [their babies] around and around until you can almost stand them on either end and they won’t bend, so tightly are they bound.”

Legacy

Overview

Riis often said he was not alone in pressing for urban reform. As the Gilded Age ended, his sentimental appeals to Christian empathy were eclipsed by more organized means to combat poverty. New college educated Progressive reformers saw unionization, woman suffrage, protective legislation, and government intervention as ways to achieve far-reaching social change. But Riis had pioneered techniques utilized in the new emerging fields of social work, investigative journalism, and photojournalism. His fieldwork in the streets; case studies of the ill and poor; documentation with a camera; use of public relations; interest in statistics; and close association with government authorities and health officers, all laid groundwork for what was to come.

When on May 25, 1914, Riis died of heart disease at age 65, Lillian Wald, founder of the Henry Street Settlement, eulogized him “for friendship and encouragement and spirited fellowship, for opening up the hearts of a people to emotion, and for the knowledge upon which to guide that emotion into constructive channels.”

Riis’s Hand

As a practitioner of palmistry, Nellie Simmons Meier had a special interest in the hands of famous people. Handprints and character analyses of celebrities formed the basis of her 1937 bestseller, Lions’ Paws. Meier wrote that Jacob Riis was

“able to present facts and details in an orderly manner of writing or speaking, thus giving a stirring word picture of the conditions which needed righting.”

Florence Kelley and the National Consumers League

When Riis was rising to fame in the 1890s, Florence Kelley, a resident of Chicago’s Hull-House Settlement, was working against sweatshops and enforcing work-safety and child labor regulations as a factory inspector in Illinois. In 1899, Kelley moved to Lillian Wald’s Henry Street Settlement in New York, and as a leader of the National Consumers League, she encouraged women to use their buying power to support fair wages, the ten-hour workday, maternal well-being, and children’s rights.

Lewis Hine and the National Child Labor Committee

The National Child Labor Committee campaigned for tougher state and federal laws against the abuses of industrial child labor, and Lewis Hine was its greatest publicist. Hine prepared many of the committee’s fieldwork reports and took some of the most powerful images in the history of documentary photography. He compiled evidence from both fields and factories, documenting children of even very young ages at work in canneries, harvesting vegetables, and keeping machines running in textile plants. Hine showed images of exploited children to audiences on a lecture circuit to sway public opinion in favor of protective legislation.

Jacob A. Riis Settlement House

From the time of its founding in the 1880s as the King’s Daughters’ Settlement, through its rechristening on 48–50 Henry Street in New York City as the Jacob A. Riis Settlement House in 1901, and to the end of his life Riis never stopped raising funds for the organization. Working with the doctors and nurses who inspected the slums, the King’s Daughters provided social services and advocacy for the poor, including sewing and nutrition classes, health care, mother’s clubs, and a summer camp for children. Riis’s much younger second wife, Mary Phillips Riis, remained actively involved in the board after Riis’s death. Now based in Queens, New York, the community-service organization provides immigration and education services and participates in a cultural exchange program with Denmark.

It took the passage of another generation and the advent of the New Deal during the Great Depression of the 1930s for activists to rediscover Riis. Inspired by Riis’s stirring call to action in How the Other Half Lives, they invoked his name to support ideas foreign to his thinking: providing jobs and housing for the poor through government programs and tax dollars. New Deal reformers like New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia and Parks Commissioner Robert Moses perpetuated Riis’s name at the Jacob Riis Houses on the Lower East Side and Jacob Riis Park in Far Rockaway, Queens.

In the 1940s, Riis’s photographs were rediscovered, and he entered the narrative of photographic history as a groundbreaking pioneer. Particularly in the 1970s, Riis had become a standard bearer for liberal reform and documentary photography and influenced photographers such as Bob Adelman and Camilo José Vergara, who have created powerful images of the urban environment.

Urban Renewal

New York City Park Commissioner and city planner Robert Moses lauded Jacob Riis in this 1949 article, describing Riis as “a working reporter with a mission” and “a doer, not merely a preacher . . . [who] laid the groundwork for the great reforms which have now passed.” The Jacob Riis Houses on Manhattan’s Lower East Side were named in honor of Riis and his campaign to upgrade multiple-unit housing available to the poor. The six-to-fourteen-story affordable housing projects were completed in January 1949 as a phase in the city’s urban renewal plan. Grouped in multi-acre complexes bordering Avenue D, they are maintained by the New York City Housing Authority and are home to some 4,500 residents.

“Old New York,” 1970

Camilo José Vergara is a Chilean-born, New York-based writer, photographer, and documentarian. For more than forty years traveling across the country, Vergara has made photographs that embrace the vitality of urban America and archive its decline. In his words: “Photography for me is a tool for continuously asking questions, for understanding the spirit of a place, and as I have discovered over time, for loving and appreciating cities.” He has also said: “I want to discover what happens to the most desolate corners of Urban America, what new activities and uses emerge, and get glimpses of their future.”

How the Other Half Still Lives

In the late 1970s, the Phelps-Stokes Fund, a philanthropic foundation, approached photographer and social activist Bob Adelman to photograph the dire state of inner-city housing in New York. The result was the production of fifty hand-bound petitions containing thirty-eight searing images of urban decay that document the heartbreaking toll taken on the inhabitants of New York’s poorest neighborhoods. In an oral interview, Adelman said that the initial idea to appeal directly to the president of the United States about the alarming state of housing for the poor in New York came from Jackie Robinson’s wife Rachel and a minister from Harlem. The resulting petition prompted President Jimmy Carter to visit Charlotte Gardens Housing Project in the South Bronx, where some of the photographs were made. The petition’s two-page text was written by Adelman’s friend and collaborator, democratic-socialist activist Michael Harrington, author of The Other America: Poverty in the United States (1962).

Originally published by the United States Library of Congress, 04.14.2016, to the public domain.