Who were the apothecaries and what role did they have in medicine?

Who Were the Apothecaries?

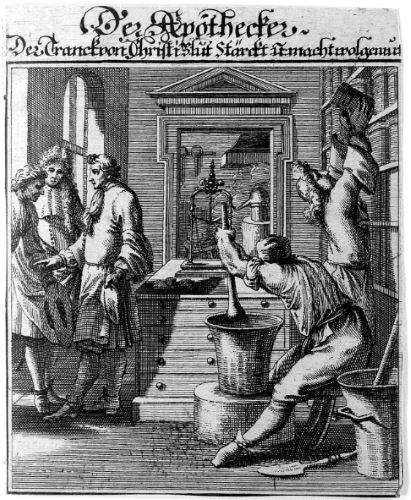

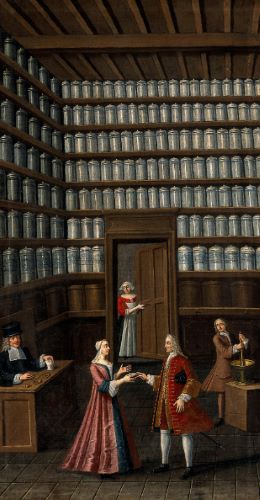

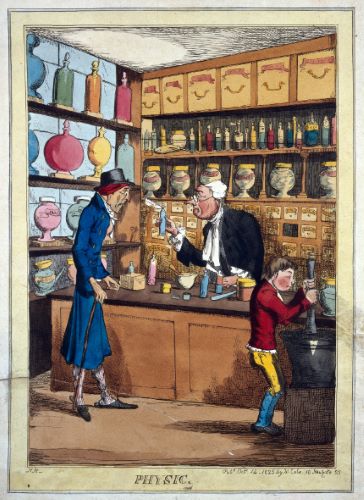

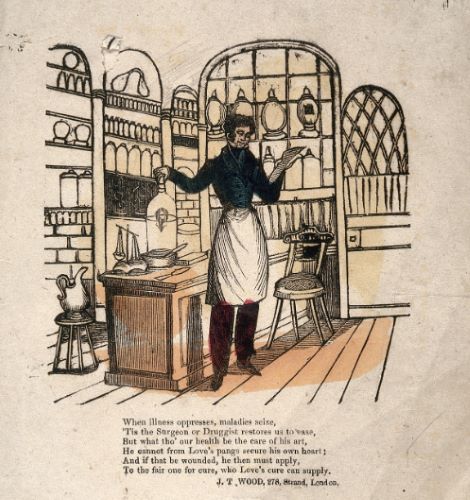

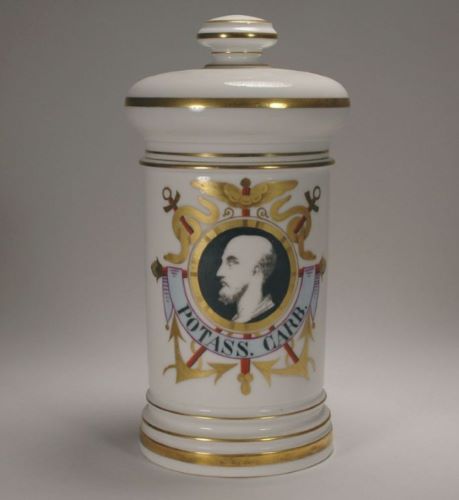

Apothecaries were a branch of the tripartite medical system of apothecary-surgeon-physician which arose in Europe in the early-modern period. Well established as a profession by the seventeenth century, the apothecaries were chemists, mixing and selling their own medicines. They sold drugs from a fixed shopfront, catering to other medical practitioners, such as surgeons, but also to lay customers walking in from the street. Their daily tasks- as distinct from those of a barber-surgeon or physician whose primary duties during this era involved related diagnosis and treatment- were thus defined by a focus on retail (sales to the public without performing other clinical roles). Their shops were designed to attract the customer, and they stored their wares in elaborately decorated jars which looked beautiful in store. Skill in chemistry was an important part of the apothecary’s identity, and these jars- which contained the ingredients used to manufacture medicines- leant prestige to their craft.

These practices were broadly comparable across Western and Northern Europe at this time, but in colonial North America medical treatment was patchier, and the distinction between different types of medical practitioners was looser. Missionaries or settlers who were pharmacists at home brought their craft with them, but they were relatively few and far between. Some colonies lacked apothecaries entirely, and physicians often dispensed their own drugs. Medicine was also often practiced by lay people, such as churchmen and governors, or housewives

In England, on the other hand, apothecaries had become organised under a professional body by the early 1600s, hoping both to prevent other practitioners stepping into their jurisdiction, and to establish legitimacy of practice. The Worshipful Society of Apothecaries (founded in 1617) had begun to regulate training through apprenticeship. The Society of Apothecaries also established a chemical laboratory for the manufacture and sale of its own drugs to society members in 1672, in order to control the production of medicines and to boost its members’ reputation for the sale of reputable remedies. In addition, the Society inspected drugs sold in premises in London, in an attempt to monitor and prevent adulteration of pharmaceuticals within the city boundaries.

Despite this, by the eighteenth century the distinction between apothecaries and physicians in England had become blurred. From the end of the 1600s, English apothecaries had been increasingly practicing patient treatment alongside the sale of medicines, acting as general practitioners and advising, prescribing or otherwise treating where a doctor had not already done so (for example, as surgeon-apothecaries). By doing so, they were stepping on the turf of the physicians. This generated a controversy that ultimately led to major changes within the apothecary profession in Britain, and meant that medical practice there developed differently than other Western countries such as France and (ultimately) the USA.

Apothecaries from the 18th Century Onward: England

British law at the beginning of the eighteenth century enforced the monopolies of the tripartite system of medical professionals, and in theory regulated their activities. However, by this time the system was under pressure, and boundaries of practice were shifting. The low numbers of elite physicians in comparison with market demand for medical care meant that the public were turning to apothecaries as a more readily available- and cheaper- alternative. Due to this imbalance in care, as well as overcrowding amongst the apothecaries, the old hierarchy began to give way. A turning point came when the Rose Case of 1704 approved this custom in law and gave apothecaries the freedom to practice physic as well as pharmacy. Throughout the eighteenth century, English apothecaries therefore developed into a group calling themselves general practitioners (and indeed, resembling modern-day GPs), and divisions between the tripartite professions further broke down. By the end of the century, the surgeon-apothecary treated a wide range of social classes. As they were not educated to the same level as the physician (nor did they share their social status) they were a great deal cheaper and were thus used more widely by the general populace for medical care.

By the 1800s the role of the apothecary had changed considerably. Whilst some apothecaries were still involved in the dispensing and mixing of drugs, few did so from a retail perspective and instead charged patients directly for remedies during clinical visits. The retail aspect of medical practice had now fallen to a separate group, the chemists and druggists. The Regency and Victorian druggists ran their profitable businesses from a street shopfront, and like seventeenth-century apothecaries, were involved in the on-site manufacture of their own medicines. They also took on an advisory role for those members of the lower and middle classes who could not afford the expensive care of a physician, but who were literate in the kinds of drugs needed to treat minor ailments. The druggists were entrepreneurial as well as medical, businessmen as well as trained practitioners. They successfully saw and filled a gap in the market left by the transition of the surgeon-apothecary to general practitioner; namely, an opportunity to sell drugs cheaply and undercut the prices charged by this new rank-and-file physician.

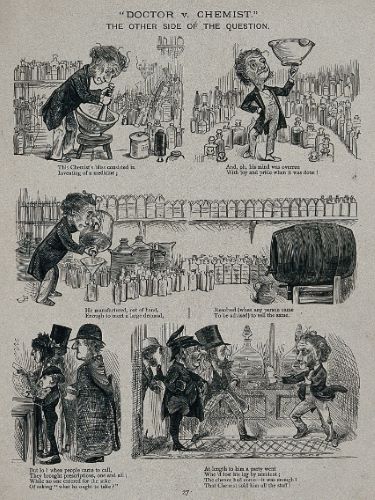

Unsurprisingly, a rivalry developed between the apothecary-GPs and the chemist-druggists over professional turf, particularly in regard to dispensing physicians’ medicines. The apothecary-GPs’ desire to establish professional distinction led to agitation for legal reform and, eventually, to legal regulation of the medical community. Between the 1815 Apothecaries Act and the 1858 Medical Act, the practice of medicine became regulated in Britain. Apothecaries became subject to rules regarding training, licensing, and practice. Chemists and druggists were excluded from this licensing, but defined as a distinct profession with their own jurisdiction. Towards the middle of the century, they began pushing for their own regulatory body in order to prevent charges of quackery, and reinforce their medical status. This culminated in the founding of the Pharmaceutical Society in 1841. Schools were then set up to teach pharmacy, and the Pharmacy Acts of 1852 and 1868 helped to regulate the sale of pharmaceuticals, and create uniform standards of training and examination. However, not all chemists and druggists educated themselves in this way, and many continued to learn the ropes via apprenticeship until late in the nineteenth century.

By the mid-1800s, the English chemist and druggist were well-established professionals, defined by their work in a wholesale and retail capacity, and catering to a population before, instead of, or in addition to, the intervention of a GP. Their services were wide ranging and competitive; they sold a variety of items, from toiletries and food to ointments and pills, and were appealing to a paying customer who (at least in the cities) had a choice of establishments to patronise. Despite this, many succeeded in making an excellent living, and had a high standing within their communities. Broadly, they functioned as a medical “first-port-of-call” for many different social classes.

Apothecaries from the 18th Century Onward: France

In France, things developed differently. Regulation and training within medical practice was centralised into state-run schools during the Revolution and continued this way into the nineteenth century. Apothecaries did not evolve into a GP role as they did in England. Instead, with the centralisation of medical training, they became regulated and licensed under the College of Pharmacy (Collège de Pharmacie), therefore developing into the modern day “pharmacist”. From this point on, graduates from the College were the sole body licensed within France for the sale of medicinal drugs, with regulation in place to protect the public from the sale of adulterated products.

The College of Pharmacy had been set up as an administrative and educational body in 1777, and after the Revolution these functions were continued under the new government alongside its additional role in licensing. In 1840, the College became part of the national university system, and by the mid-nineteenth century pharmacists in France all held a degree. The College guaranteed graduates a thorough education in pharmaceuticals and also limited entry so as to reduce competition in the market, assigning each pharmacist a regional populace similar to the parishes given to clergy. There was therefore greater continuity in the apothecaries’ daily practice than in England, as they remained specialists in the manufacture, dispensing, and sale of medicines, rather than patient treatment. However, some pharmacists did also offer health advice, and advise on which drugs a patient might require. The high level of professionalisation amongst the pharmaceutical community encouraged scientific experimentation, and French pharmacists of this period were instrumental in the progress of chemistry as a science.

French druggists, on the other hand, were an unregulated group descendant from the medieval spicers, and were only allowed to sell préparation magistrale, or items considered to have no proven medicinal value, such as homeopathic remedies and toiletries. As such they were not considered by the state to function in a medical capacity, and were not included in the new licensing legislation. As the only group licensed for the sale of medicines, French pharmacists sold a far narrower range of products than the druggists. This is in contrast to many English chemist-druggists who sold all of these different kinds of items under the one premises, and were thought of as part of the medical community, albeit an unorthodox branch. Aside from this, French pharmacists of the mid-nineteenth century were similar to their English cousins, and worked out of a shop selling to the public. The primary difference between the two professional groups lay in the regulatory and educational processes of each country.

Apothecaries from the 18th Century Onward: United States

In what would become the USA, medical practice was much less regulated than in Europe. By the 1700s, medical men were becoming more numerous in North American towns, but the boundaries between the different groups of practitioners remained blurred. Physicians tended to dispense their own drugs, and often had a shop for the purpose attached to their office. Medicines were also sold by wholesale druggists and merchants (regular shopkeepers). Apothecaries existed (as a profession defined by the possession of a shop purely devoted to the sale of drugs), but they also practiced patient care like a physician might, and sold toiletries like a shopkeeper. There was little to no regulation in practice, and there was no expectation or requirement that the drugseller be educated. Unlike in Britain and France, the medical practitioner was free to practice which parts of the profession he chose, and to call himself what he liked. This was in part due to the developing nature of North American society at this time, but also due to the individualistic attitudes within this society, which meant that standardisation was resisted as unnecessary.

This lack of regulation continued into the nineteenth century, despite an expansion of interest in pharmacy fuelled by exploration into native herbs and plants after the end of the Revolutionary War. Irregular medical and pharmaceutical practitioners flourished, such as the Thomsonians, eclectics, Reformed Practitioners, and homeopaths. The dispensing of medicines within regular practice remained largely the preserve of physician-apothecaries, who tended to both prescribe and dispense. This confusion encouraged the rise of the wholesale druggist as the group responsible for the manufacturing, mixing, and sale of drugs to the medical profession and, sometimes, the public. They were in general not medically trained, and their businesses were commercial enterprises.

This group and their activities were therefore similar in nature to the English chemist-druggist, and as the century progressed they increasingly sold directly to the public from a shopfront. The responsibility for creating effective drugs, and the profit motive in doing so successfully, promoted pharmaceutical expertise within the trade and made the druggist’s shop the forerunner of the modern American drugstore as well as the pharmaceutical industry.

Despite this, professionalisation of the druggist trade in any form did not begin until the mid-1800s, when local or state pharmaceutical societies and schools, alongside national bodies, were formed. In general, these organisations reflected the business orientations of the community and educational reform was resisted. Legal regulation at a national level did not occur until later in the century, and did not become comprehensive until after 1870. In addition, around this time the manufacture of drugs moved away from the counter and backroom laboratory to larger companies, changing the shape of the druggists’ occupation. The nature of mid-nineteenth century American pharmacy was therefore not defined by legal and professional regulation in the same way as it was in France and England, instead developing as a result of the free-market economics and laissez-faire politics of the new United States.

Inside a Mid-Nineteenth Century Pharmacy

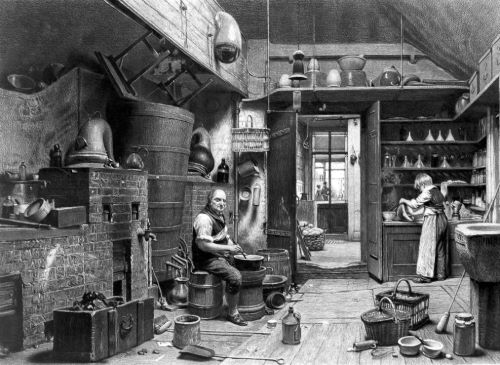

Although the role of the apothecary differed slightly from country to country, by the 1800s the profession was broadly similar across the Western world. In the mid-nineteenth century the French pharmacist and the British or American chemist-druggist would have operated from a shop something like this one.

They would have prepared medicines for customers, and sold ready made goods on their shelves. They may even have had a laboratory attached to the premises, where they would have compounded their own mixtures, and processed botanicals and minerals to make drugs.

Medical Treatment in the Nineteenth Century

In Classical medicine, the body was understood to be made up of four humours, which were balanced in health and unbalanced in disease. For many centuries, medical treatment was based around the concept of restoring balance to the body, often by so-called heroic methods such as purgatives or blood-letting, named for their drastic nature. In the nineteenth century, treatment was still remarkably similar, despite the fact that theories of disease had long moved away from Classical ideas of bodily humours.

By the eighteenth century, a mechanical concept of the body had developed. The human body was understood as made up of interconnected, constituent parts, which- if they broke down or failed in some way- could cause disease. A nosological approach to sickness had become established, whereby different illnesses were classified by their symptoms. Advances in anatomy during the early 1800s linked symptoms to changes in the body, and diseases began to be approached through physical diagnosis. Where in the body could the disease be found, where had this breakdown or failure occurred? Lesions became just as important as symptoms, and physicians associated sickness with specific organic changes. Developments in cellular anatomy and pathology, alongside technological innovations such as the microscope, meant that by the mid-nineteenth century disease was about what a clinician might find in the body. The rise of hospitals, and the practices of observation which they enabled, also encouraged a view of diseases as “types”, and an understanding that they tended to progress in the same way in various patients.

Despite these advances, it wasn’t until the advent of germ theory in the 1870s that this anatomical-pathological model of disease specificity (illness affecting a particular part of the body, i.e. through legions or structural changes) expanded to include the concept of etiological specificity as well (particular causes for particular illnesses, i.e. bacteria). Theories of contagion, for example, were debated, and miasma remained a leading theory of infection. Likewise, during the first half of the nineteenth century, laboratory scientists had started to figure out how drugs worked in the body, understanding that they did so through targeted action on a specific bodily system, rather than acting holistically upon the whole anatomy. However, until the 1890s and the discovery of drug receptors it was little understood how exactly this process occurred, and such ideas did not readily filter down into the average pharmacist or druggist’s concept of treatment.

Consequently, during the mid-nineteenth century drugs were still classified by their physiological effects- the reaction they produced in the body. Therapeutic practice in this period was therefore very much based on removing symptoms and restoring a “normal” state in the body, rather than offering a specific medicine for a specific root cause of sickness. Instead, drugs were given in order to rebalance the patient. This could be done either by stimulants, raising a debilitated body back up to health, or by lowering cases of over-excitement through the use of depletives. Symptoms were seen as indications of this imbalance and treatment was guided by them. The normal state of the body could be quantified through empirical measurements such as temperature, pulse rate, or the quality of urine, and therapies were intended to coax the diseased body back into line with these standards.

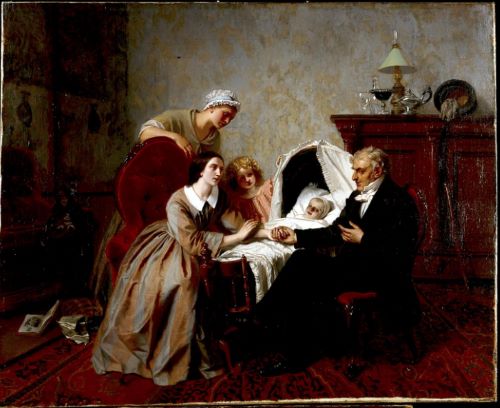

Physicians were concerned with creating measurable differences in symptoms, and pharmacists and chemist-druggists prescribed remedies which they believed to provide this normalising function for the patient. By the 1850s, this was most commonly through the use of stimulants, in order to strengthen the sick person’s enfeebled, diseased constitution. However, earlier heroic (depleting) remedies such as purgatives were still used.

Drugs and Their Manufacture in the Nineteenth Century

Herbal remedies have been in use in Europe since medieval times. From the 1500s, municipal authorities began compiling pharmacopoeias which approached medicine more scientifically. These described what drugs were in common use, how they should be prepared, and what materials were acceptable for medicinal purposes. Pharmacopoeias remained important reference tools for pharmacists for many centuries, alongside materia medica, which outlined how drugs should be used in treatment. It wasn’t until the Enlightenment and the birth of chemistry, however, that drugs and how they worked began to be properly understood. In the first half of the nineteenth century, physiologists, pharmacists and chemists across Europe and the US used chemical methods to identify and purify the drugs in various substances, isolating the active ingredients and identifying their effects in the body.

Chemistry and pharmacy grew into disciplines founded on the results of animal experiments and systematic observation. Throughout the nineteenth century more and more drugs were discovered and the production of medicines moved from the druggist’s shop to industrial pharmacies, where further scientific innovation could be undertaken with better machinery and a larger budget. Drugs that were isolated (or “discovered”) during the first half of the century included alkaloids such as strychnine, emetine, morphine, quinine, and caffeine. Salicylic acid, and later, salicin, was also isolated from willow bark.

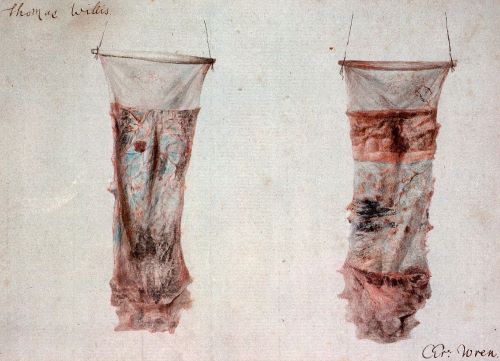

Despite this, at mid-century the production of drugs was still primarily through the use of natural products, and synthetic chemicals were uncommon until the 1880s, one notable exception being the discovery of ether and chloroform as anaesthetics. Many chemists and pharmacists still compounded their own medicines from a botanical or mineral base. They made these medicines in a variety of dosage forms, depending on the active ingredient, the purpose of the medication, and how the patient would take it. They had many different tools in their shops with which to do this, including items such as a mortar and pestle or pill cutter, to more complex types of machinery which would cut, heat, or press ingredients into different forms. Common dosage forms throughout the 1800s included powders (alongside wafers and cachets, to make them more palatable), pills, tablets, gelatin capsules, pastilles, lozenges, mixtures, tinctures, and emulsions. These were all imbibed. Ointments, lotions and plasters were applied externally, whilst enemas, suppositories, pessaries and inhalations were all intended to be taken via bodily orifice.

The various ingredients to make these medicines were the drugs kept by the pharmacist or chemist-druggist in the apothecary jars in their shop, close at hand so they could prepare mixtures on demand. If we take a closer look at these jars, we can find out more about the kinds of medication a mid-nineteenth-century pharmacist would have been making and selling.

Apothecary Jars and Their Contents

Overview

Below you’ll see what the shelves of a mid-nineteenth-century pharmacy might have looked like. You’ll notice that the jars bear Latin inscriptions of their medicinal contents. Pharmacists and chemists would have learnt about these medicines during their training, and used materia medica (handbooks to drugs and their therapeutic properties) to keep themselves up to speed in their daily practice.

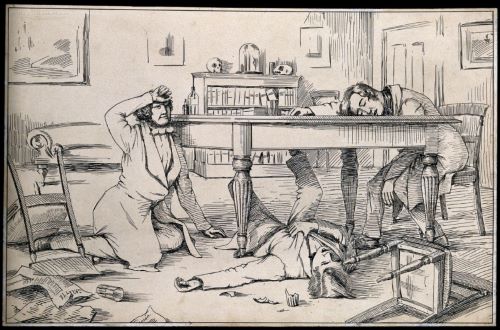

Extractum Stramonium

A potent narcotic like belladonna, Stramonium causes many side effects as the dose increases, including vertigo, headache, dim vision, confused thought, a feeling of suffocation, sleepiness, relaxation of the bowels, diuresis, and diaphoresis, all of which persist for several hours. In larger doses, it causes heart pain, excessive thirst, nausea and vomiting, a sense of strangulation, anxiety, blindness, delirium, tremors, palsy, convulsions, and death.

Used chiefly in disorders of the nervous system such as neuralgia, mania or epilepsy. Stramonium can also be applied as an ointment or poultice to cutaneous inflammations, and to the eye to dilate the pupil for cataract extraction. The berries provide the highest concentrate of the drug, whilst the leaves can be smoked to alleviate asthma. Doses can be given as a powder, tincture, ointment, or extract.

Spermaceti

Used in many different kinds of lotions, as well as for the treatment of gonorrhea and catarrh.

Spermaceti can be mixed with wax and olive oil to form cerates (a substance similar to ointment but harder and non-melting), which is applied as an adhesive in excoriations.

Potassium Bichromate

An irritant caustic, poisonous in overdoses.

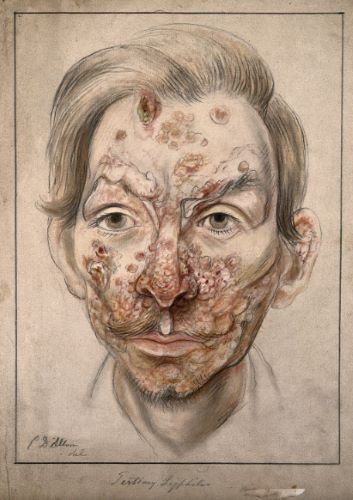

In the correct dose it is used as a treatment for syphilis, with a powder or solution being applied to syphilitic warts, as well as a pill being given orally to treat the internal disease. In large doses it is an emetic.

Folia Sennae

A prompt, efficient, and safe cathartic, being milder than other drastic purgatives. Folia Sennae is thus good for use in fevers or inflammatory cases, with pregnant women, or other vulnerable patients. Side effects can include severe abdominal pain and a bad taste in the mouth.

The leaves are infused in water or alcohol to release their cathartic properties. Folla Sennae can be made into a variety of dosage forms alongisde these infusions, including compounds, tinctures, and confections.

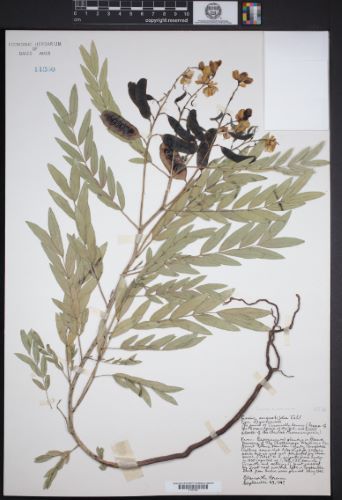

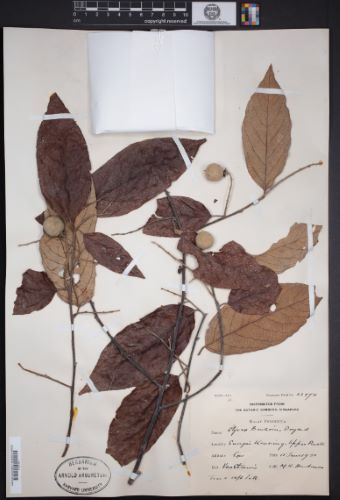

Dulcamara

The root, stalk and berries have medicinal value. In small doses, Dulcamara causes an increase in the secretions of the skin, kidneys and mucous surfaces, with some dimunition of sensibility. In large doses, it is an acro-narcotic poison.

Dulcamara is used as a diaphoretic and diuretic to treat painful cutaneous affections, rheumatism, and gout. It is also used as an expectorant for chornic catarrh. It is often prepared in the form of a decoction, but a nerve oitment may be made with the bark and roots, and used to treat bruises, sprains, and stiff joints.

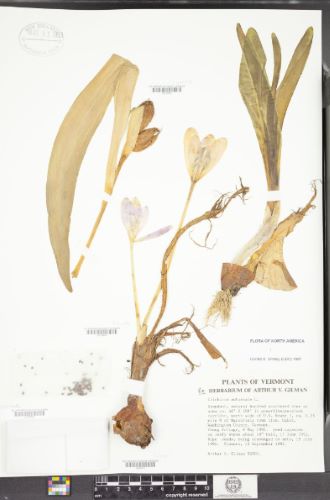

Semina Colchicum Autumnale

Toxic and potent. The bulb of Colchicum Autumnale is used as an anodyne narcotic for gout or rheumatism, and a diuretic and diaphoretic in fever. Side effects include vomiting, bloody stools, severe abdominal pain, bradycardia, and stupor, as the dose increases. It is usually administered in repeated doses until the bowels are affected.

For the treatment of gout, Colchicum Autumnale is combined with epsom salt and magnesia and prepared in a solution. It can also be mixed with opium in treatment of the kidneys or skin. It can be given as a powder, wine or tincture.

Kermes Minerale

Kermes Minerale is a preparation chiefly employed internally as an alterative in cutaneous affectations, such as secondary syphilis.

It is usually used in conjunction with mercurials. It can also be used as an emetic with similar effects to tartar emetic, in order to induce vomiting when disease is to be avoided. Sometimes useful in glandular disorders or liver complaints.

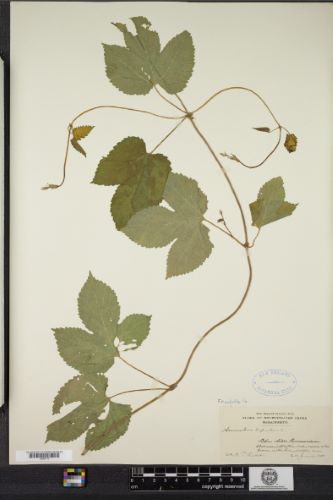

Humulus Lupulus

Humulus Lupulus is used in malt liquors as a stomachic, or alternatively as an antaphrodisiac. The seeds of the hops, lupulin, contain the active ingredient and preparations containing them are the most effective. The combination of tonic and narcotic properties makes Humulus Lupulus an excellent remedy in mania-a-potu (alcoholic mania).

Hop pillows can be used as a hypnotic. Preparations of hops given internally are effective in reducing restlessness, inducing sleep, and easing pain. Effective dosage forms include an infusion or tincuture, a powder, and pill. Topically they can be applied as a poultice to ease painful swellings or tumours.

Nux Vomica Pulvis

Highly potent. In small doses, Nux Vomica is used to treat fevers such as dysentery due to its diaphoretic and tonic properties. Larger doses cause severe side effects, including rigidity, spasms, convulsion and death from respiratory failure.

It is primarily used as a stimulant in torpid or paralytic nervous or muscular conditions, and is most efficacious when such conditions are not associated with specific lesions. For example, general paralysis, paraplegia, and amaurosis. Nux Vomica is also a specific for the bite of a water snake.

The dosage form given is usually powder, sometimes made into pill form, but it can also be given as an extract in alcohol, or as a tincture.

Myrtus Pimenta

Myrtus Pimenta is used chiefly in julaps and draughts to flavour other medicines in order to mask their disagreeable or nauseous taste.

It can also be used as a stomachic to ease indigestion.

Carum Carvi

Carum carvi are often used to relieve flatulent colic, especially in children.

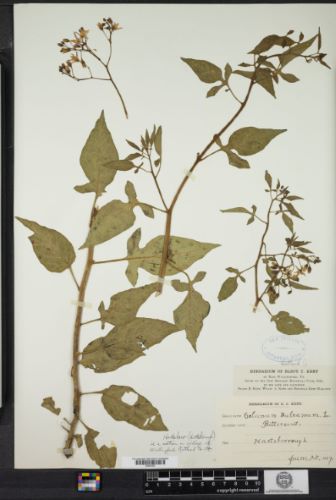

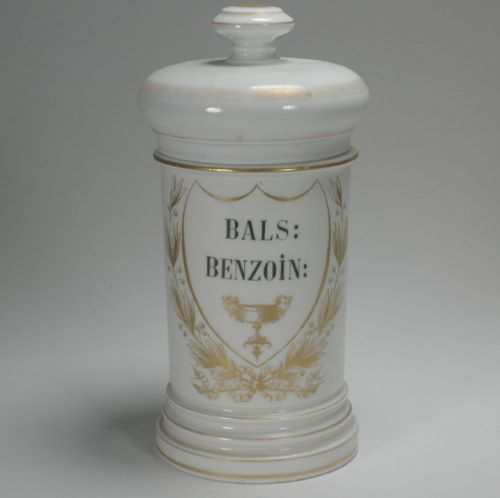

Balsam Styrax Benzoin

The resin of the tree is obtained from incisions in the bark, and then boiled in water so that the balsam settles at the bottom. It has the consistency of honey.

Used as a stimulating blennhorrhetic, expectorant and tonic. It is employed in treatment of bronchitis, chronic catarrh, asthma, gonorrhea, leucorrhea, or externally to ulcers. It is commonly given in the form of a pill, emulsion, or inhalation.

Potassae Carbonus Impurus

A salt prepared by burning plant material with close, smothering heat. It is a mixture of one part carbonic acid, one part potassa, and two or three parts water.

Potassae Carbonus Impurus is used as an antacid in dyspepsia and a diuretic in diabetes, but also in the treatment of scurvy, believed to be a dietary deficiency in potassium. It is also sometimes used as an anti-inflammatory in respiratory conditions. Dose is usually given in sweetened aromatic water.

Semina Cardamom

Semina Cardamom are employed as a corrective agent to stimulant, tonic, and purgative medicines. Often prepared as a tincture.

Pulvis Ipecacuanha

Mild. Ipecacuanha is used as a safe and dependable emetic, and in smaller doses as a diaphoretic or expectorant. In these small doses it produces depression of the pulse, and is thus also used in pulmonary and inflammatory disorders.

It is good for the treatment of dysentery and most fevers, and also for opium poisoning. Well adjusted for the remedy of spasmodic croup in children or other bronchial disorders, and to all cases where a simple evacuation of the stomach is desired. It can be given in a variety of dosage forms, depending on the intended effect or recipient. For example, as an emetic with tartar emetic, as a syrup, as a powder, or a tonic.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Stuart, ed., Making Medicines: A Brief History of Pharmacy and Pharmaceuticals, (London: Pharmaceutical Press, 2005)

- Biddle, John B., Materia Medica for the Use of Students, (Philadelphia: Lindsay & Blakiston, 1865)

- Cadeau, Emmanuel, Le Medicament en Droit Public: sur le Paradigme Juridique de l’Apothicaire, (University of Nantes: Nantes, 1997)

- Corfield, Penelope J., ‘From Poison Peddlers to Civic Worthies: The Reputation of the Apothecaries in Georgian England’, Social History of Medicine, 22:1, p.1-21

- Dorveaux, Paul, Les Pots de Pharmacie: Leur Historique Suivi d’un Dictionnaire de Leurs Inscriptions, 12th ed., (Toulouse, 1923)

- Drey, Rudolph, Apothecary Jars: Pharmaceutical Pottery and Porcelain in Europe and the East, 1150-1850, (London: Faber and Faber, 1878)

- Duffin, Jaclyn History of Medicine: A Scandalously Short Introduction, 2nd ed., (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010)

- Flannery, Michael A., ‘Reflections on 19th-Century American Pharmacy: The Notebook of Joseph H. McMinn‘, Pharmacy in History, 55:4 (2013), pp. 123-135

- Gevitz, Norman, “Pray Let the Medicines Be Good”: The New England Apothecary in the Seventeenth and Early Eighteenth Centuries,” Pharmacy in History, 41:3 (1999), p. 87-101

- Griffenhagen, George, ‘Early American Drug Containers’, Pharmacy in History, 40:2-3 (1998), pp. 93-98

- Griffenhagen, George, ‘Evolution of Drug Containers’, The Apothecary’s Cabinet: News and Notes from the American Institute of the History of Pharmacy, 8 (2004), p.5-8

- Harley Warner, John, The Therapeutic Perspective: Medical Practice, Knowledge, and Identity in America, 1820-1885, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1986)

- Higby, Gregory J., ‘Chemistry and the 19th-Century American Pharmacist’, History of Chemistry Bulletin, 28:1 (2003)

- Hill Curth, Louise, ed., From Physick to Pharmacology: Five Hundred Years of British Drug Retailing, (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006)

- Holloway, S.W.F., Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, 1841-1991: A Political and Social History, (London: The Pharmaceutical Press, 1991)

- Hudson, Briony, ed., English Delftware Drug Jars: The Collection of the Museum of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, (London: Pharmaceutical Press, 2006)

- Laughran, Michelle A., ‘Medicating With or Without “Scruples”: The “Professionalization” of the Apothecary in Sixteenth-Century Venice’, Pharmacy in History, 45:3 (2003), p. 95- 107

- Lothian Short, Agnes, ‘Apothecary Jar Inscriptions- Their Interpretation’, Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 63:2 (1970), p.145-7

- Loudon, Irving, Medical Care and the General Practitioner, 1750-1850, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1986)

- Mez-Mangold, Lydia, A History of Drugs, (Basle: F. Hoffman-La Roche & Co, 1971)

- Porter, Roy, ed., The Cambridge Illustrated History of Medicine, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996)

- Porter, Roy, The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity from Antiquity to the Present: A Medical History of Humanity from Antiquity to the Present, Vol. 1, (London: The Folio Society, 2016)

- Prüll, C., et. al, A Short History of the Drug Receptor Concept, (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009)

- Schmid, Thomas H., ‘London’s Immortal Druggists: Pharmaceutical Science and Business in Romanticism’, The Wordsworth Circle, 41:3 (2010), p. 134-139

- Sonnedecker, Glenn, ed., Kremers and Urdang’s History of Pharmacy, 4th ed., (Madison: American Institute of the History of Pharmacy, 1976)

- Simmons, Anna, ‘Medicines, Monopolies and Mortars: the Chemical Laboratory and Pharmaceutical Trade at the Society of Apothecaries in the Eighteenth Century’, AMBIX, 53:3 (2006), p. 221–236

- Thomson, Cyrus, Dr. Thomson’s Materia Medica: A Book for Everybody (New York: Geddes, 1863)

- Vayrolatti, Francois-Emond, La pharmacie à Nice du XVI’me au XIX’me siècle : Un pharmacien Niçois, Antoine Risso (1777-1845), (Nice, 1911)

- Wahltuch, Adolphe, A Dictionary of Materia Medica and Therapeutics, (London: Churchill & Sons, 1868)

- Wallis, Patrick ‘Consumption, Retailing, and Medicine in Early-Modern London’, Economic History Review, 61:1 (2008), p.26-53

- Weinberg, Fred, ‘Antiques of the pharmacy Part 1: 18th- and 19th-century artifacts’, Canadian Family Physician, 41 (1995), p.853-858

- Wilkinson, John F., ‘Old English Apothecaries’ Drug Jars’, Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, (63:2 (1970), p.137-144

- Worth Estes, J., Dictionary of Protopharmacology: Therapeutic Practices, 1700-1850, (Massachusetts: Watson Publishing International, 1990)

Originally published by the Center for the History of Medicine, Countway Library of Medicine, Harvard University, to the public domain.