Hill was put on trial for creating a public nuisance and manufacturing alcoholic beverages and was found not guilty.

Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

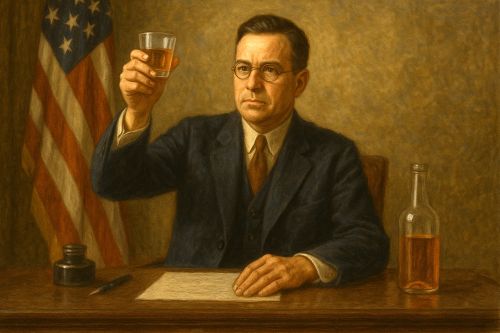

During Prohibition, Hill made wine and hard cider at home in Baltimore. He sent a letter to the commissioner, informing him of the beverages. Then he threw a huge shindig, inviting the public, and the commissioner, to sample his swill. The Maryland Representative felt that the law was “hypocritical, crooked and marked by two standards,” and he intended to protest it with a party.

The 18th Amendment, ratified in 1919, outlawed the manufacture, sale, and transportation of intoxicating drinks. The amendment, known as Prohibition, took effect in 1920. The Volstead Act provided more specifics about the definition of intoxicating beverages and how to enforce the law. Citizens and Representatives argued on both sides of the issue throughout the 1920s. Hill, a former lieutenant colonel in the United States Army, was known as one of the “wets.” But as the Baltimore Sun wrote, “nobody can be quite as wet as the Colonel.”

An Opportunity with Volstead

Section 29 of the Volstead Act piqued the Representative’s interest, because it provided an exception to the otherwise-strict standards of alcohol content. While the Volstead Act prohibited the sale and manufacture of “beverages which contain one-half of 1 per centum or more of alcohol by volume,” Section 29 explained that the penalties “shall not apply to a person for manufacturing nonintoxicating cider and fruit juices exclusively for use in his home.” It sounded like farmers could legally make and drink fermented cider and grape juice, so long as they consumed it at home and it wasn’t strong enough to make them drunk. But this part of the law had not been tested. What percentage of alcohol content constituted “nonintoxicating”? And why were farmers exempted, but not city dwellers? Hill decided to challenge the law.

In 1923, Hill prepared casks of wine in his cellar. “He has tenderly recorded the progress and temperature of his products, never failing to invite [Prohibition] Commissioner Haynes and other kindred spirits to take a hand in his investigations and to implore them to have him indicted,” the New York Times reported. Prohibition officers tacked an injunction to the door and sealed up the room. Government chemists found the alcohol content to be 11 percent. In the fall of 1924, Hill made hard cider out of apples, some from his backyard. He carefully calculated the rising alcohol content of the fermenting fruit juice. On September 17, estimating it to be at 2.75 percent, he pasteurized the cider to stop fermentation and preserve it.

Party Time

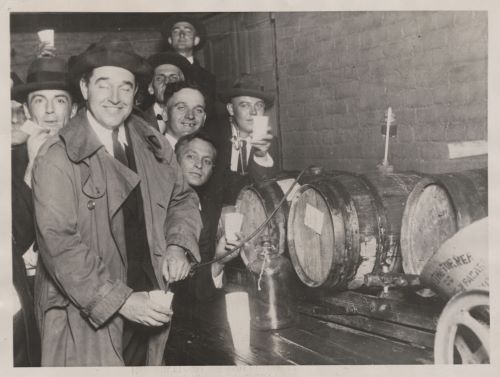

Three days later, on September 20, the Representative threw a party at Franklin Farms. His “farm” was really just the brick courtyard of his Baltimore home at 3 West Franklin Street, decorated to appear agrarian. He painted a wall to look like a red barn with cows. Hill tied an apple to one of the few small trees in the yard. And he stuck up posters advertising fairs in Hagerstown and Taneytown, Maryland, to complete the country look.

Despite the steady drizzle, more than 500 people gathered at Franklin Farms. Two men had traveled from as far as Milwaukee to attend. The Washington Post called the event Hill’s “public drinking bee.” The crowd guzzled nearly all 65 gallons of Hill’s cider, two kegs of “near-beer,” 40 dozen doughnuts, and three boxes of pretzels. Guests burned through 1,000 paper cups, which they held up to the cameras covering the event.

To Court

Although Hill had sent a special invitation to Commissioner Haynes, the official didn’t show. Hill publicly challenged Haynes to either arrest him or concede that beer and cider with 2.75 percent alcohol content were legal. Haynes finally took the bait, indicting the Representative for creating a nuisance and for manufacturing and possessing wine and cider.

The trial took place in November. The only witnesses for the prosecution were the chemists who tested the alcohol content of Hill’s 1923 vintage wine and jugs of 1924 cider. The defense, on the other hand, called a number of witnesses to testify that they had consumed the cider at the party but not become intoxicated. Judge Morris Soper refused Hill’s offer to bring two jugs of hard cider into the court so that the jury could determine for itself whether the drink was intoxicating. The jury battled for 17 hours, finally achieving a consensus at 1 a.m. that Hill was not guilty.

Hill’s “weapon was ridicule,” the Baltimore Sun wrote. “His celebrated Franklin Farms case, involving fermented fruit juices, however, was something more than a mere farce, for it succeeded in finding and publicizing one of the most serious inconsistencies in the whole prohibition setup.” The case confirmed that home winemaking was legal during Prohibition. However, Hill’s goal of making beer legal for city residents was achieved only in 1933, just as Prohibition was ending.

Bibliography

- Atlanta Constitution, 12 November 1924

- Baltimore Sun, 20 September 1924, 7 November 1924, 9 November 1924, 24 May 1941

- Christian Science Monitor, 11 November 1924

- Hartford Courant, 14 November 1924

- New York Times, 13 November 1924, 14 November 1924

- Washington Post, 17 September 1924, and 21 September 1924

- An Act to Prohibit Intoxicating Beverages, 41 Stat. 305, October 28, 1919

- Regina McCarthy, Maryland Wine: A Full-Bodied History (Charleston, S.C.: The History Press, 2012).

Originally published by the Office of the Historian, United States House of Representatives, 10.24.2018, to the public domain.