Thomson’s photographic medium possessed qualities that draw the attention of viewers and lay claim to a degree of visual authority.

By Dr. Allen Hockley

Associate Professor of Art History

Dartmouth College

Formats and Picture Size

Thomson used three formats for the scenic views in Illustrations of China and Its People. The smallest images (roughly 3.5 in. square) are grouped four to a page; medium sized images (either 8×4 or 8×5.5 in.) appear in pairs on a single page; and his large format images (either 8×9 or 8×10 in.) are given an entire page unto themselves. The large-format images are clearly of higher quality than the small- and medium-sized photographs. They showcase Thomson’s aesthetic vision, his eye for the picturesque, and his technical mastery of the photographic medium. They possess, in other words, qualities that draw the attention of viewers and lay claim to a degree of visual authority that the small- and medium-sized photographs cannot.

Thomson’s large-format photographs of Chinese scenes also compete for attention with his views of the treaty ports, which for the most part are similarly large-format images. As previously noted, Thomson’s captions for the treaty-port photos emphasize the civilizing presence of these communities. So how then does he reconcile the compelling visual qualities of Chinese architecture with his generally negative critique of traditional culture? The captions for the following series of images reveal his response to this quandary.

Fukien Temple

Thomson’s caption for his photograph of the Fukien Temple opens with an endorsement of this image as “one of the finest examples of temple architecture in the Empire.” He encourages careful examination of the picture:

The student of architecture will find the picture worthy of the closest scrutiny, for even the minutest details among the ornaments of the building are full of deep significance in reference to native art and the Buddhist or Hindoo mythology.

As an example of this “deep significance,” Thomson draws the viewer’s attention to the dragon motifs that wrap the main columns of the structure:

It will be noticed that the stone pillars of the central edifice are remarkable for grotesque yet beautiful designs, where the dragon, the national emblem of China, is seen to be the leading figure.…The dragon wields a potent influence over the people of the Empire; it forms one of the fundamental principles of their geomancy, and is supposed to exist in every mountain and stream throughout the land: its control is as firmly believed in by the Chinese masses as are the benign effects of the sunshine upon the earth.

But here Thomson’s generally informative commentary turns to criticism:

The dread of disturbing the repose of the dragon spirit as he broods over the soil of China forms one of the chief obstacles to the advance of Western science, to the opening of mines, and to the construction of railroads and telegraphs across the interior of the country.

Thomson’s combination of praise for the picturesque qualities of the site and disparagement, in this case, of superstitious impediments to Westernization, provide one means by which he extends his critique of China into his most aesthetically compelling photographs.

In effect, Thomson is juxtaposing past and present. Most of his scenic views focus on architecture erected in bygone dynasties. The brief histories of these sites and structures that Thomson often includes in his commentaries serve to isolate and fix whatever cultural importance they may have had in the past. The picturesque and aesthetic qualities of these monuments thus become their only intrinsic assets to survive into the present. This separation of aesthetic value from historical context opens up a discursive space into which Thomson can then insert descriptions of the current conditions and associations of the sites, thus enabling the juxtapositions he requires to sustain his overarching critique of China. With the Fukien Temple, he focuses on the persistence of beliefs and practices deleterious to China’s future. The following examples illustrate variations of this basic strategy.

Yuenfu Monastery

For his image of Yuenfu Monastery, Thomson’s caption first draws attention to its remote location among heavily wooded mountains and its spectacular placement in a cavern near the summit of one peak. The absence of people in the photograph emphasizes these qualities. But Thomson deliberately writes the human presence into his caption in a description of the two youths and the infirm, blind abbot who reside permanently in the monastery. Noting their daily routine, he states:

These recluses appeared to be extremely strict in their ritualistic observances; waking me every morning at sunrise by the wailing of their chants, by ringing their bells, and beating their gongs. Their meals, according to the practice of their order, consisted wholly of vegetable food, and tobacco was a luxury in which they freely indulged. Nevertheless I strongly suspect the old man to be an opium smoker.

The reference to opium would have triggered an array of negative associations for Thomson’s readers. In effect, Thomson suggests that the human (i.e., Chinese) presence in the monastery—not shown in the photograph, but documented in the caption—impinge on the picturesque and aesthetic purity of the site.

The Island of Puto

Thomson takes a similar approach and tone to his photograph of the Island of Puto. He describes the scene in glowing terms:

The group of sacred buildings, embowered in rich foliage, and backed by the granite-topped hill, the bright colors of the roofs and walls, the sacred lotus lake spanned by a bridge of marble, together make up a picture of rare, romantic beauty.

But his characterization of the inhabitants of this monastery is anything but complimentary:

This ecclesiastical population is said to number 2,000 souls, and its ranks are recruited from time to time by the purchase of young slaves, who are trained by the monks to devote their lives to the spirit crushing service of the Buddhist faith, and finally are drafted, many of them, as mendicants to the mainland to seek support for the maintenance of the monasteries, and of the lusty, lazy monks, the pious paupers who spend their years in drowsily chanting to the Buddha, and who, if dirt and sloth will foster the growth of piety, must indeed be accounted holy men.

Later in this caption Thomson confesses that he may have been too severe in his judgment, as he had “met with hospitality at the hands of many of the less devout members of the creed.” But he quickly equivocates with “I am bound to state with equal candour that the faithful mendicants, or Buddhist touters, never failed to seek a recompense.”

We cannot know for certain if Thomson’s disparaging treatment of Buddhist monks reflects his personal disposition or a broader British attitude toward China’s religions, but the later seems more likely. Christian missionaries of various denominations were hard at work with their own efforts to “civilize” China.

The Abbot and Monks of Kushan Monastery

Thomson reaffirms an anti-Buddhist bias with a photograph titled “The Abbot and Monks of Kushan Monastery.” His caption for this image draws explicit comparisons between Christianity and Buddhism. Noting first several superficial similarities between the garb of Chinese Buddhist monks and medieval Christians, Thomson then states:

The similarity between the Buddhist faith and the Roman Catholic churches may be traced even more minutely than this. Buddhists everywhere have their monasteries and nunneries, their baptism, celibacy and tonsure, their rosaries, chaplets, relics, and charms, their fast-days and processions, their confessions, mass, requiems, and litanies, and especially in Thibet [Tibet], even their cardinals and popes.

Seeking more common ground between the two faiths, Thomson then lists Buddhism’s 10 chief commandments (as opposed to the more doctrinally correct eightfold path), some of which resemble their Old Testament counterparts (theft and murder, for example). In listing these, he adopts the “thou shalt not” phrasing from the Bible. But when citing examples of what he refers to as “a multitude of minor laws,” Thomson’s choices gravitate to the seemingly inconsequential minutia of monastery life:

Every priest before he eats shall repeat five prayers for all the good things

that have happened to him that day.

His heart shall be free from cupidity and lust.

He shall not speak about his dinner, be it good or bad.

He shall not smack in eating.

When cleansing his teeth he shall hold something before his mouth.

Thomson states that no mortal can attain Nirvana unless all the maxims are strictly observed. He concludes with a less than subtle condemnation: “If this be indeed true, then the disciples of Sakyamuni in China at the present day have, I fear, but slender prospects of happiness in a future state.”

A Living Tomb

Thomson’s photograph titled “A Living Tomb” provided another opportunity to disparage Buddhist practices. The caption describes a monk who had himself entombed in this small brick structure as a means to inspire donations for the repair of a nearby monastery. As with the examples cited thus far, the greatest portion of Thomson’s caption evokes images not shown in the photographs—in this case, more extreme forms of soliciting alms. He recalls meeting a monk in a Peking lane as follows:

This wretched being sought to awaken the slothful souls of the citizens to charitable acts by beating a gong. He was a ghastly object to behold, for he had passed an iron skewer through his cheeks and tongue and strode the streets in mute agony, with blood-besprinkled robe and a face of death-like pallor.

Thomson digresses further along this path with equally disparaging and horrific anecdotes conveyed by Father Louis le Comte (1655–1728), a Jesuit priest who resided in China for three years during the late-17th century. Le Comte serves as a recognized authority to affirm a long history of Buddhism’s uncivilized practices in China, and thereby validate Thomson’s observations.

Front of Kwan-yin Temple, Hong-Kong

Chinese people appear in some of Thomson’s photographs of historic architecture, and while his captions account for their presence, his critical strategy changes little. His photograph of the Kwan-yin Temple in Hong Kong is a particularly important example. As the first image of a Buddhist temple viewers encounter in Illustrations of China and Its People, it sets the tone for all others that follow, including those discussed above that show no human presence. As the following sequence of excerpts demonstrate, Thomson’s caption for this photograph alternates favorable descriptions of the physical features of the building with negative commentary on the people that inhabit the site.

Like the majority of Chinese temples, it has been erected in a position naturally picturesque, and is surrounded by fine old trees and shady walks, commanding an extensive view of the harbour.

A never-ceasing crowd of beggars infest the broad granite steps by which the temple is approached, and prey upon the charitably-disposed Buddhists, who make visits to the shrine.

The temple front is a good specimen of the elaborate ornamentation with which these places of worship are adorned.

Thomson concludes with a description of a woman casting fortunes on the floor of the temple in hope of a favorable omen from Kwan-yin to cure her infant son of illness. This practice of juxtaposing favorable description of the architecture with disparaging commentary on Chinese people is replicated in the sequence of images he presents of the Kwan-yin Temple. The figure kneeling on the steps of the temple appears as a portrait in the next photograph.

A Mendicant Priest

In effect, the architecture-to-people transition in the caption becomes view-to-type transition in Thomson’s photographs. With the camera now focused directly on an affiliate of the temple, his characterization of Buddhist institutions becomes even more virulent. He notes that this priest’s duties include “begging for the benefit of the establishment” and performing “unimportant office for the visitors to the shrine, lighting incense-sticks, and teaching short forms of prayer.” As with many of his human subjects, Thomson paid the priest to pose for this portrait, but in this case, he received a litany of complaints about the inadequacy of the fee. It is not surprising that Thomson concluded his caption with the following:

He is a type of thousands of the miserable, half-starved hangers-on of monastic establishments in China. Equally indispensable are tribes of loathsome beggars infesting the gates of the temples, and herds of hungry, howling dogs, that live, or die rather, on temple garbage and beggars’ refuse.

The Kwo-tsze-keen, or National University, Peking

Thomson’s photograph of “The Kwo-tsze-keen, or National University, Peking” offers a subtle nuance to the critique he employs with his photographs of Buddhist institutions. This image depicts a Confucian temple, which, unlike Buddhist monasteries, seldom had residential communities. In other words, Thomson could not invoke the presence of indigenes to provide a critical perspective. For this image, the human presence Thomson so often adds into captions of historic monuments appears instead in the form of a person standing under the arch in the foreground.

Thomson offers no explanation for this human presence—the caption provides only a brief history and straightforward description of the site. Dressed in traditional costume, the person is holding a tray suspended from his neck, but we cannot see what it contains and have no way of knowing if its contents relate to the architectural monument. We do not know if this person is employed in some official function or if he is just there selling trinkets. The shadow cast by the arch impedes a clear view of the person, thus enhancing his indeterminate status.

Perhaps herein lies Thomson’s critical strategy. In both image and caption, Thomson seems determined to diminish the presence of this individual. He suggests that we simply ignore him altogether and focus instead on the historical monument. But in order to appreciate the aesthetic beauty and architectural details of the structure, our gaze must first pass by this person. Although unacknowledged, he still pollutes the site. As this Chinese subject flickers between absence and presence, we sense that he will eventually fade away under the civilizing scrutiny of Thomson’s lens.

Thomson was obviously proud of this particular photograph. Of the 200 examples in Illustrations of China and Its People, he chose this image for the gold-embossed design appearing on the album covers. And in turning this photograph into the signature icon for his entire project, Thomson completed the processes he initiated when he took the photograph and authored the caption—he eliminated altogether the human subject.

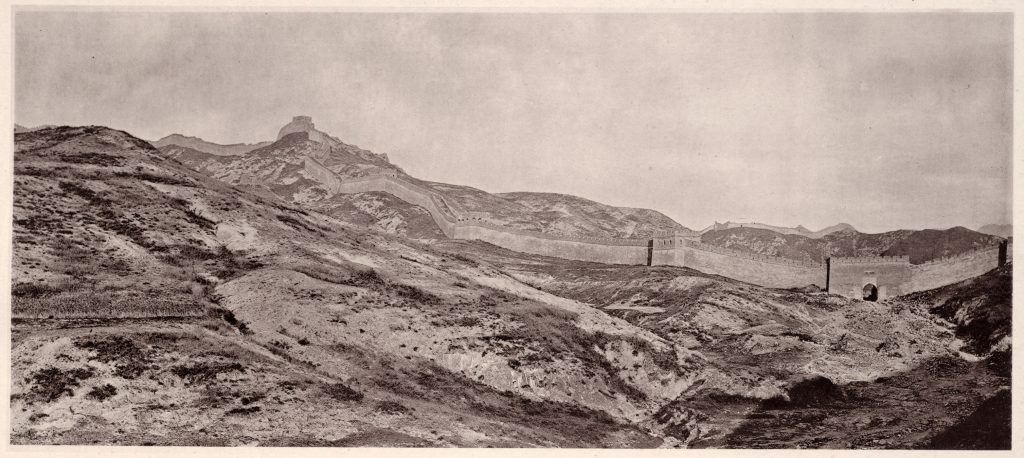

The Great Wall is No Longer Great

Thomson chose a photograph of The Great Wall to conclude Illustrations of China and Its People, and the caption he provided appropriately sums up both his attitudes toward China and those of his British audience. Thomson begins by acknowledging Western fascination with this structure: “My readers doubtless share with me in feeling that no illustrated work on China would be worthy of its name if it did not contain a picture of some portion of the Great Wall.” But he quickly disabuses admirers of the monument of any sense of grandeur:

This wall is an object neither picturesque nor striking. Viewing it simply as a wall, we find its masonry often defective, and it is not so solid or honestly constructed as one at first sight would imagine. It is only in the best parts that it has been faced with stone, or rather, that it consists of two retaining walls of stone, and a mound of earth within. In other places it is faced with brick, and there are again some other parts, of the highest antiquity, as is supposed, where we find it to consist of an earthen mound alone. Not a few travellers regard this wall as the greatest monument of misdirected human labour to be met with in the whole world[.

In many of the examples cited above, Thomson’s photographs and captions convey admiration, perhaps even fondness for the picturesque and aesthetic qualities of China’s monumental historic architecture. We might ask, then, why his characterization of the Great Wall represents such a conspicuous departure from his usual practice. The answer lies in its symbolic value—there was far more at stake with this image than any other historic site he photographed.

Thomson notes that the Great Wall was constructed to protect China from barbarian tribes invading from the north:

The Great Wall seems to me to express a national characteristic of the Chinese race. All along that people loved to dwell in their own land in seclusion, pursuing the industries and arts of peace, and to them China has ever been the central flowery land. Within it everything worth having is concentrated, and outside of it, on narrow and unproductive soils, dwell scattered tribes of barbarians ever bent on predatory excursions into the paradise of the Celestial Empire. These outer barbarians, among which we ourselves are still secretly included, have always been an endless source of trouble, now beyond the wall to the north, now along the coast on the south and east, and at other times in the mountain regions to the west.

For Thomson, China’s insistence on its innate cultural superiority and the practices of isolation this belief engendered have all been for naught. Just as it fails to embody any picturesque qualities and aesthetic value, the Great Wall has not and never will secure China’s borders. Mixing history and metaphor, Thomson uses his photograph of the Great Wall to illustrate all that was and is wrong with China. His travels extending over 4000 miles come to a close at the Great Wall, as does China’s historical isolation.

Viewers of Illustrations of China and Its People who followed Thomson’s pioneering travelogue would readily agree that the foreign presence in the treaty ports driving China to modernize—engagement with the West as opposed to isolation from it—represented China’s only hope of achieving peace and prosperity.

References

- Beers, Burton. China in Old Photographs 1860-1910 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1978).

- Edwards, Elizabeth (ed). Anthropology and Photography 1860–1920 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press in association with The Royal Anthropological Institute, London: 1992).

- Goodrich, L. Carrington and Nigel Cameron. The Face of China As Seen by Photographers & Travelers 1860–1912 (New York: Aperture Foundation, 1978).

- Maxwell, Anne. Colonial Photography and Exhibitions: Representations of the ‘Native” and the Making of European Identities (London and New York Leicester University Press, 1999).

- Morris, Rosalind C. “Introduction.” Photograhies East: the Camera and Its Histories in East and South East Asia. Edited by Rosalind C. Morris, pp. 1-28 (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2009).

- Pearce, Nick. “Photographs of Beijing in The Oriental Museum, Durham,” Apollo (March 1998): pp. 33-39.

- Pinney, Christopher. Camera Indica: The Social Life of Indian Photographs (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997).

- Pinney, Christopher. “The Parallel Histories of Anthropology and Photography.” In Anthropology and Photography 1860-1920, edited by Elizabeth Edwards, pp. 74-95 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press in association with The Royal Anthropological Institute, London: 1992).

- Poignant, Roslyn. “Surveying the Field of View: The Making of the RAI Photographic Collection.” In Anthropology and Photography 1860-1920, edited by Elizabeth Edwards, pp. 42-73 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press in association with The Royal Anthropological Institute, London: 1992).

- Ryan, James R. Picturing Empire: Photography and the Visualization of the British Empire (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997).

- Santoyo, Maria. “The Travels of a Victorian Photographer.” In Sheying: Shades of China 1850-1900, pp. 23-28 (New York: Turner, 2008).

- Spencer, Frank. “Some Notes on the Attempt to Apply Photography to Anthropometry during the Second Half of the Nineteenth Century.” In Anthropology and Photography 1860-1920, edited by Elizabeth Edwards, pp. 99-107 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press in association with The Royal Anthropological Institute, London: 1992).

- Thiriez, Regine. Barbarian Lens: Western Photographers of the Qianlong Emperor’s European Palaces (Amsterdam: Overseas Publishers Association, 1998).

- Thomson, John. China and Its People in Early Photographs: An unabridged reprint of the classic 1873/4 work (New York: Dover Publications, 1982).

- Thomson, John. Illustrations of China and Its People, a Series of Two Hundred Photographs with Letterpress Description of the Places and People Represented. 4 vols. (London: Sampson Low, Marston Low, and Searle, 1873 [vols. 1 and 2] and 1874 [vols. 3 and 4]).

- Warner, John. China The Land and Its People: Early Photographs by John Thomson (Hong Kong: John Warner Publications, 1977).

- Worswick, Clark. Sheying: Shades of China 1850-1900 (New York: Turner, 2008).

- Worswick, Clark and Jonathan Spence. Imperial China: Photographs 1850-1912 (New York: Pennwick Publishing, 1978).

- Wue, Roberta. Picturing Hong Kong: Photography 1855-1910 (New York: Asia Society, 1997).

Originally published by Visualizing Cultures, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 United States license.