The Wycliffite Bible may have been an open source project that elicited the first expression of hacker ideals.

By Dr. Kathleen E. Kennedy

Global Professor

British Academy

University of Bristol

Introduction

Like literature and law, the Bible was part of the medieval information commons, and therefore part of the bedrock of our current media culture. As did so many Europeans, the medieval English enjoyed a long tradition of bible translation. In medieval England, the Bible’s text functioned as an information commons and anyone could borrow from it. Yet, it was bible translation that proved to be the firing point for the beginnings of a proprietary information culture. Archbishop Thomas Arundel attempted to outlaw bible translation in England in 1409. Named for John Wyclif, an Oxford theologian and posthumously declared heretic, the collaborative bible translation known as the Wycliffite Bible was the first complete Bible in English and drew the balance of Arundel’s ire. At least one of the translators and editors who worked on the Wycliffite Bible was concerned enough about the larger implications of Arundel’s rights grab that he penned a work that today stands as the first statement of hacker values. This author argued for the commonness, openness, and freedom of biblical text in the face of Arundel’s attempt to render it proprietary. Nevertheless, the threat against this portion of the information commons was not realized effectively in the fifteenth century and instead the Wycliffite Bible “went viral,” laying down a thick layer of media sediment and stifling all previous translations. Today the Wycliffite Bible remains by far the most plentiful Middle English text.1 The Wycliffite Bible may have been an open source project that elicited the first expression of hacker ideals but the translation turned out to be so popular that this defensive posture was unnecessary.

The layers of this essay will progress from oldest and lowest to higher and newer. First, I will make a case for bible translation as evidence for an information commons in medieval England. Attempts at effacing this stratum were made by Arundel and others, however, and the middle portion of the essay will explore evidence of this attempt at cultural change. Although Arundel’s efforts proved to be ineffective, they were noticed by at least some translators and editors. One self-conscious response to Arundel’s agenda forms the final section of this essay.

As a derivative, a translation, the Wycliffite Bible was hugely popular and its spread was so wide that it effectively overlaid all previous bible translations, creating a durable new cultural stratum. In software we speak of a “category killer,” a product so excellent that nothing can surpass it until conditions change, and the Wycliffite Bible was such a product. The Wycliffite Bible saturated the market for bible translation. The verb “saturated” suggests water, and we should think of the sediment that travels in moving water and that settles eventually to create new layers of earth. Like sediment, the Wycliffite Bible covered what came before thoroughly and imposed a unity where there had been diversity. Yet it did this, apparently, by beating the competition in the marketplace, not because it was supported by an institution.

As Ralph Hanna has amply demonstrated, hacking biblical texts was a passion of the later medieval English; it was a tradition.2 Hanna explores the tradition of bible translation in later medieval England at length, and in the end deter-mines that the Wycliffite Bible “became a full substitute and drove out . . . competing biblical versions.”3 By expanding “bible translation” to its widest limits, including paraphrase, versification, commentary, apocrypha, and even considering literature with a heavy scriptural background, Hanna demonstrates that from the beginning of the fourteenth century translated scripture was at the heart of English literary culture. Among the earliest examples of London Middle English are manuscripts that provide “reasonably direct access to biblical texts,” and Hanna goes so far as to consider prose bible translation as “one centre of the early London book-trade.”4 Hanna rests his conviction concerning changes in English literary culture in the late fourteenth century on the Wycliffite Bible: “the very fidelity to the Latin text and the absence of sectarian additions . . . made the book useful to a general interested audience” and he argues that in the fifteenth century the Wycliffite Bible largely supplanted the richly diverse biblical texts that preceded it.5

Metamorphic Scripture

In geologic metamorphosis, rock undergoes physical change, sometimes at a chemical level, due to pressure and temperature changes. We might think of texts in the information commons as liable to undergoing such physical alteration, and scripture translation offers a range of examples of this metamorphosis. The shift from a plethora of scriptural translations to a narrowed selection that Hanna uncovers can be illustrated using the psalms. Four different English translations of some or all of the psalms circulated in fifteenth-century England, together with an English translation of the psalms in the Book of Hours based on the Wycliffite Bible, and of course the Wycliffite Bible itself. All treated the text of the Bible as common, open, and free. All of these versions of the psalms are hacked. The variation in the four translations is broad, suggesting that there were few limits on this information commons. Nevertheless, the overwhelmingly popular translation was the Wycliffite translation: it was idiomatic, and unlike the rest, capable of being read on its own, without commentary.

Three of the translations represent varying levels of para-phrase and produce metamorphic derivatives of the psalms, that is, psalms mixed with other material and formed anew under pressure. Richard Maidstone, Thomas Brampton, and John Lydgate all wrote versions of psalms that date to the very late fourteenth or early fifteenth centuries. All three were likely clergy. Lydgate’s psalm translations show the widest range and run the gamut from pure allusion to close literal translation.6 Maidstone’s editor, Valerie Edden suggests that subsequent copyists felt free to revise his psalms to fit their own purposes, and I would add that this is consonant with treating the Bible as an information commons.7 Ultimately, the freedom to produce and to copy these translations into the Tudor period argues that the Bible was a traditional information commons for the medieval English.

The manuscript tradition of these paraphrases show widely varying treatment: few copies are complete, and many include only one or a few psalms8 Control of even the form of the text was impossible: in Brampton’s poem, the presence of the Latin text of the psalms appears to be optional: some manuscripts include the Latin verses together with the English paraphrase and some do not.9 Most of these psalm translations were copied into religious and devotional anthologies. In one manuscript not far from his copy of Lydgate’s Psalm 102, John Shirley copied Brampton’s Penitential Psalms.10 Maidstone’s poem often turns up next to works by, or at-tributed to, Richard Rolle, an earlier scripture translator. Both Brampton and Maidstone occur alone in pamphlet form only occasionally.11 The decoration of these anthologies ranges from luxuriously illuminated, to finely flourished, plainer copies, to un-illuminated, un-flourished copies.12

A group of Books of Hours illustrates another way in which biblical text might be metamorphosed, in this case translating a popular prayer-book and inserting text derived from the Wycliffite Bible itself. The fourteenth century saw the development of the Book of Hours, an outgrowth of the psalter that became the most popular book of the late Middle Ages in England as on the Continent.13 The core devotion of the Book of Hours was the Hours of the Virgin and this consisted mostly of psalms. I have argued elsewhere that sixteen copies of the Book of Hours translated into English make use of versions of the Wycliffite Bible for their psalms.14 Psalms make up approximately 77% of the text of the Book of Hours, and so all of these volumes are made up mostly of the Wycliffite Bible.15 In Books of Hours we see the Wycliffite Bible treated as common and used freely thanks to the translators who had opened the Latin text into English. Whatever their religious beliefs, the developers of the English Hours made use of a popular scripture translation to speed their development of a derivative of a different popular text, the Book of Hours.

Manuscript evidence argues for the Bible continuing to be an information commons throughout the fifteenth century in the face of attempts at institutional control.16 In the end, we can turn to a Latin Book of Hours containing Maidstone’s paraphrase of the Penitential Psalms to argue for the commonness of, even appreciation for, such metamorphic scriptural texts.17 This volume features fine illuminated borders and an occasional historiated initial all executed by artists in Gloucester, likely at the Abbey of St. Peter.18 Important for this essay is the replacement of the usual Latin Penitential Psalms with Maidstone’s English paraphrase. This English replacement text is highlighted by a sumptuous, nearly half-page historiated initial by the Oriel Master.19 There is no shyness or hesitancy about swapping English paraphrase for the Latin text here: the information commons is visible in this Book of Hours, and attention is called to it with an arresting miniature. Clearly the scriptural information com-mons was healthy in the fifteenth century, but changes were also in the air.

Defending Richard Rolle’s Intellectual Property

The fourth version of the psalms—and the most popular be-fore the Wycliffite Bible—was rendered by the fourteenth-century hermit Richard Rolle.20 Rolle’s translation of the psalms predated Wyclif and so according to the Constitutions of Arundel (1407-1409) that outlawed the Wycliffite Bible, Rolle’s translations were technically legal throughout the fifteenth century. The English Psalter is itself a text illustrating stratification, as it includes each psalm line in Latin, followed by Rolle’s strictly literal English translation (Nicholas Watson calls the translation “manifestly not self-sufficient”), followed by Rolle’s commentary explicating each verse.21

As we might expect, Rolle’s English Psalter was itself treated as part of an information commons, and about half of the manuscripts we have today include interpolations, or additions by subsequent readers.22 Michael Kuczynski and Kevin Gustafson find it entirely likely that some of the interpolators saw their revisions as of a piece with Rolle’s own work.23 Some interpolations encourage the believer through a time of persecution. Kucyznski connects this type of psalm hacking with identification with the psalmist himself in his own persecution.24 Gustafson sees oversight as the crucial impossibility, as “any such text could become a vehicle for heterodoxy,” and “readers . . . [were] making the text so dangerously unstable.”25 The multiplicity of potential readings shows how the biblical text functions like a spiritual tool, as in most instances the audience determined the relative orthodoxy of the reading. As with open source code today, once a text was released, it could be variously developed, and a text left as open as Rolle’s “tantalizingly ambiguous” English Psalter could be developed in many different directions that could then be interpreted in many different ways.26 In other words, editors simply took a useful common text and further developed it. Furthermore, these editors followed what would be considered good hacker etiquette today and attributed the original to Rolle.27

At the same time as copyists felt comfortable developing Rolle’s text, a new sense of a fixed, proprietary text was also beginning to manifest. Surely this is related to the developing notion of what it means to be an author, of intellectual property as we know it, and to burgeoning humanism, spreading from Italy through France and reaching into England in Wyclif’s lifetime. Wyclif and his followers tangled desperately with theologian Jean Gerson, who may well have developed the notion of a “public intellectual” and who exercised an unusual control over the dissemination of his own works.28 I do not mean to suggest here that Gerson’s ideas drove the attempt to control texts directly, but both directly through activity on pan-European Church councils and indirectly through his writing, Gerson and other scholars were developing and spreading new ideas about the importance of fixed, inalterable texts.

In evidence that such ideas were filtering into England in this period, a preface added to one copy of Rolle’s English Psalter asserts that Rolle’s translation is not common but proprietary. This preface emphasizes the care that Rolle took with his translation, links Rolle’s writing with his miracles, and emphasizes that anyone altering Rolle’s text was acting like a heretic, like a Lollard, or follower of Wyclif.29 The author of the preface argues that to revise the English Psalter is not illegal, but impious. While Rolle himself seems to have been sanguine about the openness of manuscript tradition, this prefacer attempts to claim the Psalter as Rolle’s intellectual property, and therefore cuts against the grain of tradition.

In the preface, Rolle’s position as a Jerome-like holy, learned translator is emphasized in a characterization that Kuczynski calls God’s “scribe-prophet.”30 Rolle “glossed the psalter that follows in English expertly.”31 Included in a list of Rolle’s miraculous accomplishments is making “many a holy book.”32 The prefacer describes Rolle again as a sort of Jerome when he says “this holy man expounds: he follows the holy doctors of the Church;/ And in all his Englishing; he follows the Latin text./ And makes his translation complete: short, good, and profitable/ for men’s souls.”33 Rolle is not creating anything new here, the prefacer claims, but closely follows standard commentaries (“holy doctors of the Church”) in his exegesis and the Latin in his biblical translation. The result is “complete,” or all a pious reader could need: short, good, and profitable.

For the prefacer, Rolle’s learning and holiness prevented the hermit from doing harm to Jerome’s text just as medieval tradition had it that Jerome’s learning and holiness prevented him from doing harm to biblical text. Therefore the prefacer cautions that anyone else amending Rolle’s work was doing wrong: “there is no error in it: nor any deceit or heresy,/ But every word is solid as stone: and is absolute truth/ Whoever will copy this I advise him: copy carefully line by line,/ And write no more than is here written: or else I tell him, not you it will not be right.”34 The holy text, expounded by a holy man is compendious and perfect, fixed like a stone: a secure, true textual act. Copying such a text ought not be undertaken lightly, but be done carefully. No mention is made of abbreviation. The prefacer is apparently afraid only of expansion.

Note here how even this restriction of the commons fails to reach the level of control characteristic of modern intellectual property. The prefacer allows, even encourages copying, in a way foreign to current law. However, as today, no derivation is to be made: copyists must acknowledge Rolle’s masterful work, and replicate it perfectly without adding anything. In fact, the prefacer describes a situation not unlike the rights and limitations contained in the license on this present book, a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommerical-No-Derivs 3.0 Unported License. Today that license is considered progressive and advocates a publishing process more open than normal. When the prefacer wrote, his stance was progressive and advocated a dissemination process more proprietary than normal.

The “error,” “deceit,” and “heresy” the prefacer references are directly linked with textual expansion associated with an evangelical lollardy making free use of common texts:

This Psalter has been copied by evil men of lollardy:/ And afterward it has been seen to be engrafted with heresy./ They said then to uneducated fools that this Psalter is in its entirety/ A blessed book of their schools: Richard of Hampole’s Psalter!/ This they claim craftily to make people believe their teachings/ To reel them in, and in so doing destroy them, against the faith, a great foolishness/ And slander this holy man foully with their crafty, wicked wiles.35

As Kuczynski notes, “to be grafted into” connotes a slicing of heresy into the holy man’s text.36 Adding insult to injury, the prefacer blames the Lollards for claiming Rolle’s book as one of their own, using the holy man’s book and his brand, his name, to lure in the unsuspecting to heretical conversion. Here we have intellectual property anxiety clearly expressed. For the prefacer, anyone making changes to Rolle’s text, any hackers, are pirates, Lollards, and heretics. Ironically, the text of this copy of the English Psalter is itself an interpolated text (though not clearly a heretical one).37 Despite his desire to do so, the prefacer could not fence the psalms: they were an in-formation commons and audiences ensured that they circulated freely.

The Viral Wycliffite Bible

The tradition of the Bible as an information commons received a direct challenge early in the fifteenth century and the prefacer of Rolle’s English Psalter offers evidence that this challenge met with some support. In Archbishop Thomas Arundel’s infamous Constitutions of 1407-1409, translating the Bible or reading such a translation could lead to one being suspected of heresy.38 Contemporary events led to the moment in Article 7 of the Constitutions when Arundel claimed the English Church’s property rights over the text of the Bible, and denied anyone the right “by his owne authoritie, [to] translate any text of the Scripture into English” and demanded “that no man read any such boke.”39 No mere flash in the pan would have goaded Arundel into such a statement, but only a translation that was open and already circulating freely.

That Arundel could have attempted to enforce Church control over scripture is itself interesting. The Church had traditionally exercised control over the interpretation of scripture, but to extend interpretation to include translation, or derivative works, had not been attempted since Jerome. As we have seen, the Bible was part of the information commons, and had been translated and developed as long as there had been an English language. Yet whether he wrote before or after Arundel’s pronouncement, the Rolle prefacer reminds us that the information commons was being reassessed more broadly in this period. Arundel put institutional heft behind such aspirations of control.

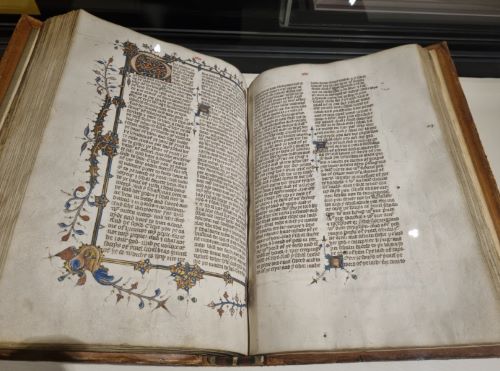

Unusually collaborative for its time, the Wycliffite Bible project looks to us today remarkably like an open source pro-ject. Currently there is general acceptance that, while Wyclif himself argued for the importance of bible study and that the Bible should be available in English for both clergy and lay-people, it was a group of his followers rather than himself who labored at translating the Bible into English.40 Eric Raymond notes that modern open source projects follow a unique release pattern: they stay in beta for a long time while users and developers work together to identify and fix bugs, but when a full, official release is made, it is a solid, workable product.41 The Wycliffite Bible follows this open source pat-tern, having a beta version, the Earlier Version (EV), which was “absolutely and sometimes incomprehensibly faithful to the literal sense and word-order of the Latin.”42 Scholars believe the EV to have been begun in the mid-1370s.43 Raymond cautions that “beta software is notoriously buggy.”44 The EV was certainly “buggy,” but improvements began to be made swiftly and accretively, and the more readable, more colloquial Later Version (LV) came to be the standard release. It was the LV, completed by 1400, which became the bestseller described by Hanna, and EV’s copying ceased rap-idly around 1400.45 Christina von Nolcken estimates that 85 percent of the roughly 250 extant manuscripts contain text in LV.46 In computer hackers’ terms, the LV was the stable release, designed to “go viral.”

Given the information commons out of which the Wycliffite Bible came, it may not be surprising that the LV was designed to be a broadly useful text, with an easily replicable structure. Moreover it was as ecumenical a text as could be: no one in the Middle Ages and no one today has found any heretical material in the text of the translation itself. It would appear that the diverse group of developers who gathered to accomplish this enormous task achieved a text anyone could use, regardless of religious affiliation. The LV was not copied to be hidden under a bushel.

The many extant copies prove that the Wycliffite Bible spread widely as it was copied from the late fourteenth into the early sixteenth century, and individual copies can be associated with a range of pre-Reformation owners.47 At least eleven copies were owned by religious: monks, nuns, and priests.48 Five copies were owned by members of the royal family.49 A further four copies were owned by lesser nobility such as the gentry, or members of the wealthy urban mercantile classes.50 This by no means exhausts the list of known owners. In addition, copies that no longer exist are recorded in wills, inventories, and library lists.51 The extant, signed copies show a geographical spread from Newcastle in the north, Norwich in the east, Shrewsbury in the west, and the Isle of Wight in the south. By the early sixteenth century a copy of the Wycliffite Bible had been translated into Scots.52 There is nowhere the Wycliffite Bible did not go, and like a layer of sediment spread by a relentless flood it reached across the length and breadth of the island’s media culture.

The General Prologue as README.TXT

Despite the evident popularity of the Wycliffite Bible, the threat posed by Arundel and the potential for a shift toward proprietary control of parts of the information commons was clearly taken seriously in some quarters. What is today called the General Prologue was written by a Lollard who took part in the Wycliffite Bible’s development, and though it is contained in only a few copies of the Wycliffite Bible, it forms the earliest recorded statement of hacker values.53 Using rhetoric familiar to hackers today, the General Prologue’s author claimed that the Bible was a commons and should therefore be both open in the vernacular and freely available. Rita Copeland claims that the Lollards desired to “releas[e] the text [of the Bible] from the imprisonment of mere language so that it [could] be a newly collective property,” but I argue that there was nothing new about treating the Bible as an information commons: what was new was defending why one did so.54 As a threat to a traditional information commons developed in the form of an anti-translation position promoted by the Church hierarchy and supported by the government, so too did a vocal response to that threat.

Readme files are theoretically written for a mixed audience, but practically speaking today they are read, if at all, only by other programmers. The README.TXT file includes general information about a program, including credits to the developers and copyright information, as well as installation instructions. These files also include more specialized information used by programmers alone, such as the changelog, or record of changes made to the program since the last version, together with a list of known bugs.

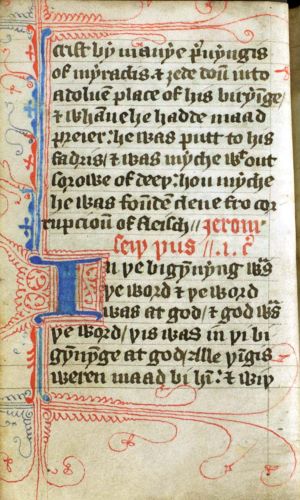

Like a medieval readme file, the General Prologue of the Wycliffite Bible appears to be a sort of medieval version of modern developer release notes and FAQs, available for the “full release” of this particular open source project.55 The General Prologue seems to have been written with a mixed audience in mind, just as readme files are today, and with similar contents. As such, it provides both basic instruction in biblical interpretation and, in Chapter 15, careful description of the methodology used by the team of translators. This is not quite a changelog, but it is close. As Hudson notes, the methodology described in this project description is deceptively simple: to have accomplished it would have required an enormous number of hours and a group of dedicated scholars.56 In Chapter 15, the prologue author, calling himself “Simple Creature” (pseudonymity is an ancient hacker tradition) also outlines the reasons why the project was undertaken, and these emphasize the hacker ideals of commonness, openness, and freedom.57

It should be noted how the General Prologue offered to provide another layer of accretion over the Wycliffite Bible, but its limited circulation did not create the necessary coverage for a new stratum. If we think of the Wycliffite Bible as a category killer that overshadowed other, partial translations, then it was a significant layer of cultural deposit. In contrast, the General Prologue’s layer of accretion turned out to be far less widespread in the medieval period than the volume to which it was so seldom attached. Accretion this may have been, but it was localized only, and we must assume that few Wycliffite Bible owners read it. Most of us never open the developer or FAQ files on computer programs today, either. Nevertheless, it is worth considering this rare prologue be-cause the author reminded his audience of the tradition of the Bible as an information commons at a time when institutional forces were attempting to exert control over that commons. These hacker sentiments might never have been voiced had it not been for the threat to that tradition posed by the Constitutions.

That Simple Creature was writing largely, though not exclusively, for other translators and editors, for other hackers, has not been credited before now. However, the Wycliffite Bible was an enormous, and therefore unusual, translation enterprise and its outlawing in 1409 rendered it even more special, particularly when its immediate popularity is considered. Much about Chapter 15 specifically might be of interest to other medieval hackers, as they could have had professional interest in the methods used in such a monumental task, together with professional curiosity about the reasons behind it. From the perspective of the early fifteenth-century, if the Church was attempting to restrain scripture translation, there was no way to know what else might be curtailed. In this sense Chapter 15 might also be viewed as a consciousness-raising gesture in an effort to begin to build a coalition out of an educated, skilled community only very recently threatened.

The General Prologue claims to give readers an insight into the working practices of the Wycliffite Bible developers, and these parallel those of open source project teams today. The team that labored to bring the Wycliffite Bible into being may well have been a diverse group whose beliefs ran the gamut from orthodox to heretical: we have no way of knowing for sure. Moreover, this team developed the Wycliffite Bible in stages comparable to those of open source software. Further, as we have already seen, once released, the Wycliffite Bible was developed and reused in ways that the original developers might not have anticipated. Regardless, the popularity of the Wycliffite Bible is exactly what the Lollards declared should happen: the common text of the Bible should be open to the people in the vernacular and should move freely among the community of English people of whatever confession.

The General Prologue begins by arguing for the commonness of the scripture for all Christian communities: “because Christ says that the Gospel shall be preached throughout the whole world.”58 The Prologue continues by quoting (and translating) Jerome on Psalm 87: “Holy Writ is the scripture of the people for it was written so that all people should be familiar with it.”59 For the “common profit,” translating the Bible is “common charity.”60 It was a common project: the Prologue calls the team “a variety of colleagues and assistants” who undertook each stage of the process, from gathering materials, to establishing a best Latin text, to seeking out additional expert linguistic advice, to making a preliminary translation, to revision of that translation.61 By including a plea to educated readers for revision of any faults, the author encouraged continued participation in this open source project.62 This invitation to further revision was a commonplace in the medieval information commons, and it was a tradition eventually contested by the humanists.

Openness was a goal of the translation. The goal, stated in similar language several times, was to make the biblical sentence “as open or even more open in English than in Latin”63 The Prologue goes on to give grammatical examples of “opening” Latin using English.64 Jerome’s standard of sense-translation lies at the heart of this open source project: “this will in many places make the meaning open, where to English it literally would render it dark and difficult.”65

Openness is one of a group of terms that mark a so-called “Lollard vocabulary.” It was closely linked to the Lollard program for lay access to the Bible and implied easy access through clarity of translation.66 For Lollards, this openness related to unmediated access to the divine intention conveyed in scripture.67 “Open” scripture is contrasted with “dark” scripture, but Lollards insisted that clerical mediation was not necessary to comprehend scripture in either case, for those in charity. Nevertheless, Nicole Rice has shown that “openness” was a popular adjective in non-Lollard circles as well. In these uses clergy might still assist in mediating between “dark” scripture and “open,” and the sense of accessibility stands behind either interpretation.68 “Openness” continues to refer to access even today, though the nuances involved in that access may change over time.

Freedom is addressed too, as this translation must be envisioned to circulate freely in order “to save all men in our realm whom God wishes to be saved.”69 The Prologue accuses the clergy of closing, of limiting, access to scripture when they “prevent Holy Writ from circulating as much as they may.”70 Freedom is also implicit in the Prologue’s list of other translations of the Bible. First written in Hebrew and Greek, the Bible was translated into vernacular Latin, had in the past been translated into Old English, and was currently available in several Continental vernaculars. Why, the author asks, are others free to access the Bible in their own languages, but anglophones alone are left without scripture in the common tongue?71 The author of the General Prologue implies that the Bible should be freely available.

Because of the existence of the medieval information commons, I disagree with Mary Dove’s belief that “EV was never intended to be copied as a translation in its own right, but that translators producing the LV lost control of what happened to the EV in the early 1380s.”72 In the 1370s the Wycliffite Bible project was part of a tradition of treating the Bible as an information commons. Indeed, the Wycliffite Bible may have been one culmination of that tradition. The EV and the LV were both produced to be copied, to become part of the information commons in their turn. Without more information I do not think we can assume the collaborators wanted to control either EV or LV. The Bible in Middle English attracted interest from many quarters in the following decades and the tradition of bible translation eventually came to be questioned. In an era increasingly willing to condone institutional control (however imperfect) over texts, the author of the General Prologue emphatically expressed the significance of treating the Bible as an information commons.

Conclusion

By the time Lydgate was translating the psalms in the fifteenth century, hacking biblical text into Middle English had over one hundred years of tradition behind it. We must assume that much of the audience for these texts knew exactly what they were reading. The linguistic landscape of fifteenth-century England was too complex for us to assume that these English texts served only as glosses to Latin texts, any more than hacked statutes were simple cribs. Glosses they may have been, sometimes and for some people, but clearly these texts also stood on their own and served as their traditional counterparts. The Bible was a traditional information commons, and the Wycliffite hackers like the author of the General Prologue voiced strong opposition to Arundel’s effort at containment. More effective than the manifesto in the General Prologue, however, was the product of that production team’s labors, the Wycliffite Bible, which spread freely across England and was developed further throughout the century.

In this essay we see the beginning of the changes that transform the textual world in the sixteenth century, and that continue to inform textual culture today. In the fifteenth century attempts at controlling the information commons remained local and imperfect, and they failed to effectively sediment a new textual order. However, the local accretions gradually grew together. Approached from a modernist, or even an Early Modernist perspective, the century between Thomas Arundel and Thomas More may seem long, and the lives of the two men entirely unconnected. However, when perceived from the other vantage, one can see unspooling behind both men the hundreds of years during which the culture of the information commons had permeated society. From that perspective such an enormous change taking a mere century to develop momentum seems swift indeed.

See endnotes and bibliography at source.

Chapter 3 (55-79) from Medieval Hackers by Kathleen E. Kennedy (Punctum Books, 01.16.2015), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported license.