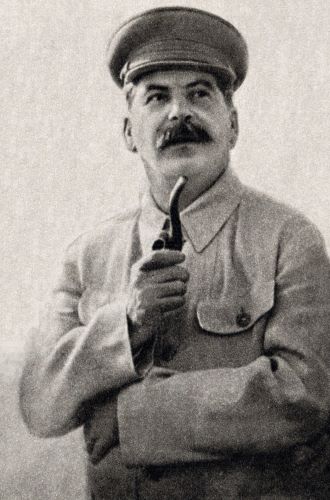

The Stalinist use of psychiatry to suppress dissent represents one of the most complete and consequential transformations of political conflict into diagnostic authority.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: When Disagreement becomes Illness

In the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin, political disagreement was progressively stripped of its status as thought. Criticism of policy, skepticism toward official narratives, or calls for reform were not treated as positions to be debated or even crimes to be tried in the conventional sense. Instead, they were increasingly reframed as evidence of psychological abnormality. To oppose the system was to misunderstand reality itself. Disagreement became illness, and illness required treatment rather than argument. This transformation marked a decisive shift in how power neutralized dissent, moving beyond coercion through law toward delegitimization through diagnosis. By redefining opposition as a defect of mind rather than a conflict of ideas, the Soviet state recast political struggle as a medical problem, one that could be managed quietly, indefinitely, and without public justification.

This medicalization of opposition did not emerge accidentally or at the margins of governance. It followed logically from the internal claims of Stalinist ideology itself. Stalinism presented Marxism-Leninism not as one interpretive framework among others, but as a scientifically grounded account of historical necessity. The Party positioned itself as the custodian of objective truth, uniquely capable of reading the laws of history and directing society accordingly. Within such a framework, rational disagreement was not merely unwelcome. It was conceptually incoherent. If the system embodied historical reality, then opposition could only arise from distortion, delusion, or defective consciousness. The dissenter was not wrong in the ordinary sense. He was misaligned with reality itself, suffering from a failure of perception rather than a difference of judgment. Political conflict became a problem of mental orientation, not ideological disagreement.

Stalinist psychiatric repression functioned as a political technology designed to eliminate dissent without engaging it. By recoding criticism as psychological pathology, the Soviet state avoided the risks inherent in trials, debates, or public justification. There was nothing to refute if the critic was deemed incapable of rational judgment. Psychiatric confinement replaced ideological confrontation, allowing the state to present repression as care and silencing as treatment. Loyalty became a marker of mental health. Skepticism became a symptom.

By examining how Stalinist authority transformed disagreement into illness, this situates psychiatric suppression within a longer historical pattern of power pathologizing opposition. The Soviet case represents an extreme but revealing endpoint, where the language of medicine completed the work that law and theology had performed in earlier eras. When the state claims the right to decide who is sane, dissent ceases to exist as a political act. It survives only as diagnosis, and truth no longer needs to answer.

Ideological Certainty and the Infallibility of the System

Stalinist ideology rested on a claim of absolute certainty that left no conceptual space for legitimate disagreement. Marxism-Leninism, as interpreted by the Soviet state, was presented not as a tradition of critical analysis or a framework open to revision, but as a completed science of history. Its conclusions were treated as empirically verified truths rather than provisional interpretations subject to debate or falsification. History, according to this framework, moved according to discoverable and inexorable laws, and the Communist Party alone possessed the intellectual authority required to interpret and apply them correctly. Political authority derived not merely from control of institutions or coercive power, but from presumed epistemic superiority. To govern was to know, and to know was to rule.

Error could not be symmetrical. If the Party’s understanding of history was correct by definition, then opposition could not represent an alternative reading of events grounded in reason or evidence. It had to be a deviation from reality itself. Dissenters were therefore positioned outside the bounds of rational interpretation. To question collectivization, industrial priorities, or political purges was not to propose a competing analysis of social conditions. It was to reveal a failure to grasp objective truth. Ideological disagreement was transformed into a diagnostic signal, indicating misalignment with historical necessity rather than political disagreement.

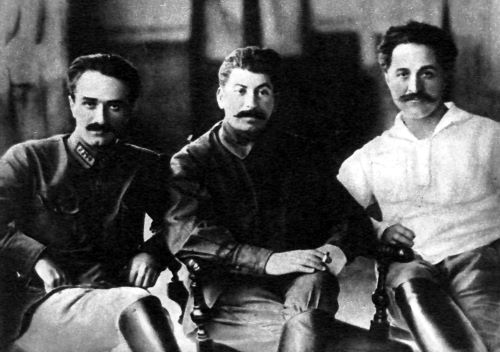

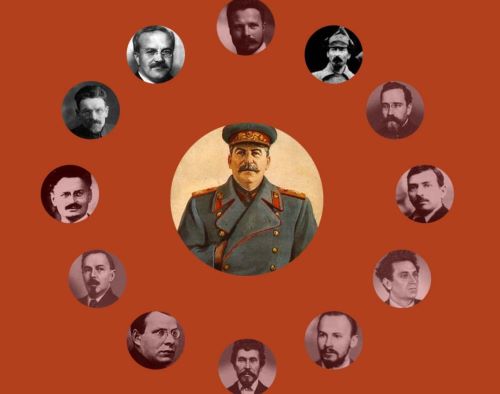

This logic was reinforced through the personalization of ideology under Stalin, whose interpretations increasingly functioned as final authority. Stalin’s position as theoretician, arbiter, and enforcer collapsed doctrinal correctness into personal loyalty. Because the system claimed infallibility, any challenge to its conclusions implicitly challenged the rational order of the world it described. Disagreement therefore appeared not merely subversive but nonsensical. The Party did not simply govern policy. It governed meaning, reality, and historical truth. To dissent was to stand in opposition not only to leadership but to history itself, a stance that could only be explained through irrationality, confusion, or psychological defect.

Ideological certainty also reshaped the emotional expectations of political life. Proper belief was expected to produce confidence, optimism, and ideological enthusiasm. Doubt, anxiety, or hesitation signaled internal defect rather than thoughtful caution. The ideal Soviet subject did not merely assent intellectually to Party doctrine. He displayed emotional alignment with it. This fusion of belief and affect made psychological evaluation a natural extension of ideological enforcement. Emotional nonconformity became further evidence of cognitive malfunction.

Debate then lost its function entirely. Argument presumes uncertainty, contestability, and the possibility of revision. Stalinism denied all three. The system could not be wrong, only misunderstood. Once that premise was accepted, opposition no longer demanded refutation. It demanded explanation in pathological terms. Ideological certainty laid the groundwork for psychiatric repression by redefining disagreement as proof of mental failure rather than political difference.

From Political Enemy to Psychological Deviant

In the early years of Soviet rule, opposition was framed primarily in political and legal terms. Enemies of the revolution were identified as class adversaries, counterrevolutionaries, or saboteurs whose resistance could be punished through arrest, exile, or execution. The logic was adversarial and overt. The state acknowledged conflict, even as it criminalized it. Dissent was dangerous, but it was still intelligible as opposition grounded in interests, loyalties, or ideology.

By the 1930s, this framing began to shift in response to Stalin’s consolidation of power and the systematic elimination of organized political alternatives. If socialism was advancing inexorably and class enemies had ostensibly been defeated, persistent dissent posed a conceptual contradiction. Opposition could no longer be explained solely as resistance by identifiable groups with material interests. It appeared instead as an anomaly within a supposedly unified socialist society. This tension placed pressure on the regime’s explanatory framework, encouraging a new interpretive move. Dissent was no longer treated primarily as hostility or sabotage, but as deviation from a rational and historically correct consensus. The problem was no longer who opposed the system, but why opposition still existed at all.

Language played an important role in this transformation. Critics were increasingly described as suffering from “false consciousness,” “reformist delusions,” or an inability to comprehend objective reality. These terms blurred the boundary between ideological error and psychological defect, collapsing political disagreement into cognitive failure. Disagreement was recoded as misperception rather than judgment. The dissenter did not oppose the system because of lived experience, moral conviction, or alternative analysis, but because his mind was improperly aligned with socialist truth. Political conflict migrated from the realm of interests and arguments to the realm of mental functioning, where it could be neutralized without engagement.

This shift was reinforced by the personalization of authority under Stalin. As Stalin positioned himself as the definitive interpreter of Marxist-Leninist doctrine, deviation from his line appeared increasingly inexplicable in rational terms. To disagree with Stalin was not merely to oppose a leader or a policy. It was to contradict the scientific laws of history as he articulated them. Such contradiction demanded explanation beyond politics. Psychology offered a solution, allowing the state to account for dissent without conceding error, contingency, or legitimacy.

The move from enemy to deviant also softened the surface of repression while deepening its reach. Criminal punishment acknowledged agency, however negatively. Psychiatric framing denied it. The dissenter was no longer an actor making choices but a patient exhibiting symptoms. This reframing stripped opposition of moral and political standing. One cannot argue with a delusion. One can only diagnose it. The state insulated itself from critique while presenting its actions as protective and corrective rather than punitive.

By recasting opponents as psychologically deviant, the Soviet state completed a crucial transition in the logic of control. Opposition was no longer something to defeat through confrontation or coercion. It was something to explain away as abnormal. The dissenter ceased to be a political subject and became a diagnostic object, defined by presumed defects rather than articulated claims. In this way, Stalinist power moved beyond repression toward a more total form of governance, one that regulated not only behavior and speech but the very conditions under which disagreement could be recognized as rational thought at all.

Psychiatry as an Instrument of the State

As political dissent was increasingly reclassified as psychological deviation, psychiatry offered the Soviet state a powerful and flexible instrument of control. Medical authority carried a moral and cultural weight distinct from police or courts. It invoked expertise, neutrality, and care rather than punishment or coercion. By absorbing dissent into psychiatric categories, the state could suppress opposition while presenting itself as rational, humane, and scientifically grounded. Confinement was no longer framed as retribution for political crime. It was treatment for a pathological condition. In this way, psychiatry supplied a language through which repression could be exercised without openly acknowledging political conflict or ideological vulnerability.

This repurposing of psychiatry did not require the wholesale invention of false diagnoses. It relied instead on the expansion and reinterpretation of existing concepts. Vague categories such as delusion, paranoia, or impaired reality perception could be stretched to encompass political nonconformity. Criticism of the system became evidence of distorted thinking. Persistence in dissent confirmed pathology. Because diagnostic criteria were elastic and authority-driven, psychiatric judgment could be aligned seamlessly with political priorities.

Institutional structures reinforced this alignment at every level. Psychiatric hospitals operated within the broader apparatus of the Soviet state, subject to the same surveillance, pressures, and ideological expectations as other institutions. Physicians were expected to serve social stability and political correctness alongside patient care. Professional advancement, access to research, institutional funding, and even personal safety were often contingent on cooperation. In such an environment, resistance carried serious risk. The boundary between medical assessment and political compliance steadily eroded, not always through explicit orders, but through tacit understanding. Psychiatry became less a space of independent clinical judgment and more a conduit through which state power quietly flowed.

Psychiatric confinement offered distinct advantages over traditional imprisonment. It was indefinite, often lacking clear legal limits or fixed sentences. Release depended not on time served but on demonstrated “recovery,” which in practice meant ideological compliance, emotional submission, or prolonged silence. The patient was trapped in a circular logic. Continued dissent proved illness. Apparent acceptance suggested improvement. The very structure of psychiatric treatment incentivized conformity while denying the legitimacy of resistance.

This system also removed dissent from public visibility. Trials produced records, witnesses, and potential martyrs. Psychiatric hospitalization produced patients whose voices were discredited by definition. Their testimonies could be dismissed as symptoms. Their suffering could be interpreted as clinical rather than political. In this way, psychiatry erased opposition more thoroughly than overt repression, dissolving it into medical anonymity.

By integrating psychiatric authority into the machinery of governance, the Soviet state completed a critical transformation in how power operated. Political disagreement no longer needed to be outlawed, debated, or publicly refuted. It could be treated as a disorder of perception. Psychiatry did not merely assist repression. It redefined the terms of reality itself, determining who was capable of perceiving truth and who was not. Once that authority was claimed, dissent ceased to exist as a political act and survived only as diagnosis, managed quietly within institutions designed to correct minds rather than answer arguments.

Loyalty as Mental Health

Loyalty was no longer understood merely as political alignment or obedience to authority. It became a marker of psychological normalcy. To affirm the system’s legitimacy, to express confidence in its claims, and to display emotional enthusiasm for its goals were taken as evidence of a sound and healthy mind. Mental health was defined not by autonomy or critical capacity, but by ideological harmony. The well-adjusted Soviet subject was one whose beliefs, emotions, and expressions aligned seamlessly with official truth.

This redefinition of mental health extended beyond explicit political statements into affect, demeanor, and everyday behavior. Optimism, confidence, and ideological certainty were treated as signs of psychological stability and maturity. Doubt, ambivalence, or hesitation were interpreted as warning signs of inner disorder. Skepticism suggested confusion. Silence implied withdrawal or passive resistance. Even emotional restraint could be read as detachment from reality or insufficient commitment to socialist ideals. In this environment, mental evaluation became inseparable from political performance. One did not merely think correctly. One felt correctly, at the right moments and with the proper intensity. Emotional conformity functioned as a continuous diagnostic indicator.

The medicalization of loyalty also inverted traditional assumptions about sanity and reason. Under ordinary conditions, the ability to question authority, recognize contradiction, or register moral discomfort might be considered signs of cognitive health and ethical awareness. Under Stalinism, these capacities became liabilities. To perceive injustice, inconsistency, or suffering as systemic rather than accidental was to risk being labeled maladjusted, pessimistic, or delusional. Psychological health was redefined as acceptance of the system’s moral universe, including its sacrifices and contradictions. The healthier the mind, the less it resisted. Emotional and intellectual compliance were recoded as therapeutic outcomes rather than ideological submission.

This framework completed the transformation of dissent into illness. Once loyalty itself was medicalized, opposition could only appear pathological by definition. The state did not need to prove critics wrong. It only needed to demonstrate that they were unwell. By equating ideological compliance with mental health, Stalinist power collapsed political judgment into psychiatric assessment, ensuring that disagreement could no longer speak as reason. It could only appear as symptom.

The Erasure of Political Argument

The psychiatric framing of dissent completed the removal of opposition from the realm of political thought. Once critics were reclassified as patients, their claims no longer required engagement, rebuttal, or even acknowledgment. There was no argument to answer if disagreement itself was understood as a symptom. Political conflict was dissolved into medical judgment, and the possibility of persuasion disappeared entirely. The state did not defeat ideas. It denied that ideas were present.

This erasure had practical and archival consequences. Trials, however coercive, still produced records of charges, defenses, and counterclaims. Psychiatric confinement produced case files rather than transcripts, diagnoses rather than arguments. What survived were descriptions of behavior, affect, and alleged delusions, stripped of political content. Critics were remembered as unstable personalities rather than thinkers with articulated positions. The documentary trail preserved pathology, not dissent.

This process reshaped collective memory in subtle but profound ways. Because opposition was recorded as illness rather than disagreement, later accounts encountered it only in medicalized form. Political critique vanished from the historical narrative, replaced by stories of individual breakdown, maladjustment, or personal tragedy. The system appeared uncontested not because it was universally accepted, but because rejection had been rendered illegible as thought. Silence was mistaken for consensus. Absence of argument became evidence of unanimity. What could not be spoken could not be remembered, and what could not be remembered could not inspire future resistance.

This final stage of repression was also the most complete and enduring. By erasing political argument rather than merely suppressing it, the state insulated itself from both contemporary and retrospective critique. There were no alternative visions to recover, no suppressed debates to reconstruct, no intellectual countertraditions preserved in exile or underground print. What remained was a narrowed political imagination in which dissent appeared inconceivable rather than forbidden. In this way, psychiatric suppression achieved what censorship and terror alone could not: the disappearance of opposition as a recognizable form of reasoned disagreement, not only in practice but in memory itself.

Fear, Self-Surveillance, and the Internalization of Diagnosis

Psychiatric repression did not function solely through institutions and confinement. Its most enduring effects operated at the level of everyday life, shaping how individuals monitored themselves and others. The possibility of being labeled psychologically unwell produced a pervasive atmosphere of fear that extended far beyond those formally accused. Because dissent could be interpreted as illness, individuals learned to treat their own thoughts, emotions, and doubts as potential liabilities. The threat was not merely punishment, but reclassification as mentally unfit, a status that erased credibility and agency simultaneously.

This fear encouraged a form of self-surveillance that penetrated deeply into private life. Citizens learned to evaluate not only what they said, but what they felt and how those feelings arose. Doubt became dangerous even when unspoken. Skepticism toward official narratives, grief over state violence, or discomfort with ideological contradictions had to be carefully managed, suppressed, or reinterpreted as personal weakness. Inner life itself became subject to discipline. Individuals rehearsed acceptable emotional responses, corrected their internal reactions, and learned to narrate their own discomfort in nonpolitical terms before any external authority intervened. The state did not need to observe constantly. People learned to observe themselves.

Self-surveillance also reshaped social interaction in systematic ways. Conversations became guarded, coded, and highly performative. Expressions of enthusiasm were exaggerated to preempt suspicion. Silence was calculated rather than natural, timed and framed to avoid interpretation as withdrawal or dissent. Emotional neutrality carried risk, as it could be read as psychological detachment or latent opposition. In this environment, sincerity itself became unstable. What mattered was not belief, but the visible performance of psychological alignment. The line between genuine conviction and defensive mimicry blurred, producing a society in which public life was dominated by ritual affirmation rather than shared understanding.

The internalization of diagnosis further dissolved trust between individuals. Because dissent could be framed as illness, concern for others became entangled with fear and obligation. A neighbor’s anxiety, sadness, or critical remark might indicate not only political unreliability but psychological instability. Reporting such behavior could be rationalized as protective rather than punitive. Surveillance acquired a moral dimension. To identify instability was to act responsibly. The language of mental health allowed denunciation to be framed as care, masking coercion beneath concern.

These dynamics reshaped subjectivity itself. Individuals began to understand sanity in explicitly political terms, measuring their own mental health by their capacity to accept official reality without strain or contradiction. Discomfort was pathologized. Moral unease was treated as immaturity or maladjustment. The healthiest mind was one that no longer experienced tension between lived experience and ideological claims. Psychological adaptation became a survival strategy, rewarding emotional numbness, compliance, and selective forgetting while penalizing reflection.

The result was a society disciplined from within, where fear no longer required constant external enforcement. Diagnostic categories had been internalized as self-regulating norms. Citizens policed their own thoughts, corrected their own emotions, and managed their own silences in advance of any intervention. Psychiatric repression achieved its most effective form when it no longer needed to be applied. Once individuals learned to experience dissent as a sign of inner defect, state power no longer depended primarily on institutions or violence. It lived inside the subject, shaping what could be thought before it could ever be said.

Conclusion: When the State Decides Who Is Sane

The Stalinist use of psychiatry to suppress dissent represents one of the most complete and consequential transformations of political conflict into diagnostic authority in modern history. By redefining disagreement as illness, the Soviet state eliminated the need for argument, persuasion, or justification altogether. Opposition was not defeated through debate, nor disproven through evidence or ideological contest. It was rendered unintelligible by being reclassified as a failure of perception, judgment, or psychological balance. Once critics were understood as mentally unwell, their claims no longer demanded response. The burden of proof vanished. Truth no longer needed to answer because it had already declared its challengers incapable of understanding it. Power secured itself not by winning arguments, but by dissolving the very conditions under which argument could occur.

What made this strategy especially powerful was its fusion of ideology, medicine, and morality. Psychiatric repression did not present itself as violence but as care. Confinement became treatment. Silence became recovery. The state positioned itself as guardian not only of political order but of psychological health, collapsing loyalty into sanity and dissent into pathology. In doing so, it enlisted medical authority to naturalize repression, disguising coercion behind the language of expertise and compassion. Power did not merely punish opposition. It explained it away.

The consequences extended far beyond those directly confined or diagnosed. By medicalizing dissent, the state reshaped subjectivity itself and altered how individuals related to their own thoughts. Citizens learned to experience doubt as danger, skepticism as weakness, and moral discomfort as personal defect. Fear was no longer confined to institutions. It migrated inward. Self-surveillance replaced open repression as the primary mechanism of control. Political judgment ceased to function publicly because it had been neutralized privately, recoded as a sign of instability rather than conscience. The most effective silencing occurred not in hospitals or files, but within the mind itself, where disagreement learned to disqualify itself before it could ever be expressed.

The Stalinist case offers a lasting warning. When the state claims the authority to decide who is sane, political life collapses into classification rather than contestation. Disagreement ceases to function as a civic act and becomes a diagnostic problem to be managed. The health of any political system depends on its willingness to tolerate dissent as intelligible, rational, and human, even when it is disruptive or uncomfortable. Once sanity becomes a loyalty test, truth no longer persuades. It only diagnoses.

Bibliography

- Arendt, Hannah. The Origins of Totalitarianism. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Company, 1951.

- Bociurkiw, Bohdan R. “Political Dissent in the Soviet Union.” Studies in Comparative Communism 3:2 (1970), 74-105.

- Dobson, Miriam J. “The Post-Stalin Era: De-Stalinization, Daily Life, and Dissent.” Explorations in Russia and Eurasian History 12:4 (2011), 905-924.

- Etkind, Alexander. Warped Mourning: Stories of the Undead in the Land of the Unburied. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2013.

- Figes, Orlando. The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalin’s Russia. New York: Metropolitan Books, 2007.

- Fitzpatrick, Sheila. Everyday Stalinism: Ordinary Life in Extraordinary Times. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage Books, 1975.

- —-. Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason. New York: Vintage Books, 1961.

- —-. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–1977. New York: Pantheon Books, 1980.

- Getty, J. Arch. Origins of the Great Purges: The Soviet Communist Party Reconsidered, 1933–1938. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985.

- Goffman, Erving. Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates. New York: Anchor Books, 1961.

- Havel, Václav. The Power of the Powerless. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 1979.

- Hudson, Hugh D., Jr. “Zakonnost’ and Dissent: Post-Stalin Repression of Political Dissidents In Historical Perspective.” The Historian 39:4 (1977), 681-701.

- Jaworsky, Ivan. “Soviet Dissent, or Dissent in Soviet Russia?” The Russian Review 84:3 (2025), 513-516.

- Kotkin, Stephen. Magnetic Mountain: Stalinism as a Civilization. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995.

- Powell, David E. “Controlling Dissent in the Soviet Union.” Government and Opposition 7:1 (1972), 85-98.

- Sharlet, Robert. “Dissent and Repression in the Soviet Union.” Current History 73:430 (1977), 112-117.

- Snyder, Timothy. Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. New York: Basic Books, 2010.

- Stalin, Joseph. Foundations of Leninism. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1924.

- Tucker, Robert C. Stalin in Power: The Revolution from Above, 1928–1941. New York: W. W. Norton, 1990.

- van Voren, Robert. Cold War in Psychiatry: Human Factors, Secret Actors. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2010.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.11.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.