Examining the lengthy history of print journalism in America to provide a context for understanding the digital age.

By Danny Crichton, Ben Christel, Aaditya Shidham, Alex Valderrama, and Jeremy Karmel

Introduction

Newspapers and print journalism in the digital age have changed dramatically from their roots. Once the exclusive source of news for people across the world, newspapers today are confronting greater competition from more places than ever before. At the same time, there is growing concern that journalism on the internet is failing to uphold the basic values of journalism and that American democracy is increasingly at risk due to the lack of quality information.

At the heart of our analysis is the notion of the Fourth Estate, a term coined by Edmund Burke to describe how journalism acted as a fourth branch of government, holding public officials accountable and informing citizens of prominent issues. This mission has been at the heart of the journalistic enterprise for the past few centuries. The question today is whether new forms of news like social media and blogging represent a better form of the Fourth Estate, or whether the decline in print media is leading to a simultaneous decline in the robustness of this unofficial branch.

This website analyses the trends that are taking place today in journalism. We begin by looking at what the Fourth Estate is, and what it means for the practice of journalism. Next, we present a lengthy history of print journalism in America, to provide the context needed to understand the changes underway in the digital age. Third, we include an analysis of the economics of journalism, followed by an exploration of the effects of how journalism has been affected by the internet. Finally, we have conducted five interviews with journalists that are confronting the digital age themselves to give a real look at how the internet is changing the practice of journalism today.

History

Early America

In the early days of the American colonies, newspapers were the sole provinces of the wealthy administrators of the English Crown. The cost was high, typically several pounds per week. At the time this was more than the average colonist’s monthly wages. These periodicals typical dealt with issues like European warfare and diplomacy and colonial statutes, important matters for English gentlemen but not for the colonists. As a result, there were rarely more than 2,000 subscribers for any given periodical. Until 1750, few colonies had more than a single paper in operation at any given time.

Nonetheless, the colonies had unusually high literacy rates. It is commonly estimated that around 90% of whites in northern America were literate by the early 18th century. By comparison, only half of the white populace in England was literate at that time. This was largely a result of the mostly protestant makeup of the northern colonies. Protestantism stresses literacy in order to ensure that worshipers could understand holy texts without reliance on the priesthood. In this way, Protestantism created a fertile ground for the newspapers that were to come.

Newspapers and the Revolution

After 1750, the situation changed dramatically. As the English crown began to regulate and tax more activities in America, politics became highly relevant to the daily lives of all those living in the colonies. Newspapers sprang up across the colonies, often with expressly political intent. One particular important moment for American newspapers was the publications of a series of newspaper articles entitled Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania to the Inhabitants of the British Colonies in 1767. The series argued that because the colonists were not represented in the English Parliament, they therefore could not properly tax them. This series was published in over twenty papers in the colonies.

A few years later, a group of experienced debaters led by Samuel Adams used newspapers to inform 260 towns on issues of overbearing English policies and invited each to express their own opinions on the matters. Incredibly, most of the towns responded, with community leaders drafting documents and the whole town voting on the responses.

Thomas Paine’s Common Sense is rightly understood as the document that did the most to foment a revolutionary spirit in America. Its unprecedented sales of over half a million copies in the first year made it the most read political document of its time. Less appreciated is the extent to which Common Sense owed its success to the broad circulation of newspapers throughout the country. The tract received tremendous publicity from the papers. Furthermore, R. Bell, the pamphlet’s publisher, relied heavily on the distribution networks created by the newspapers in order to ensure the document would reach as broad an audience as possible.

News in the Republic

From the moment America gained its independence, the founding fathers recognized the importance of the press. However, until the federal government became firmly established in 1787 there were few large-scale changes to the system that had served the colonies before the revolution. The ratification of the constitution changed the situation completely. A relatively little known clause in the constitution, the Postal Clause, quickly brought a much larger scale system of distribution of information into being. This clause allowed the federal government to obtain a monopoly on mail delivery and use government funds and legal rights to expand the postal network.

A long line of postmaster generals, starting with Benjamin Franklin, did just that. In 1788 there were less than 100 post offices but by 1800 there were almost 1,000. Twenty years later there were 4,500. A large and connected mail routing system allowed citizens of the republic to send news to one another but the effect of the post office on news accessibility was far greater than that.

Those in charge of the federal government decided that even more important than private mail was the availability of newspapers to the public. In 1791, Madison remarked that Congress had an obligation to improve the “circulation of newspapers through the entire body of the people”. He helped champion the Post Office Act of 1792. The act included a provision for the delivery of newspapers by the Post Office at extremely low rates for delivery of newspapers. For the century following the passage of the Post Office Act, newspapers often accounted for more than 95% of the weight of mail transported by the post office, but never made up for more than 15% of the revenue. The result of this large indirect subsidy of the fledgling industry was enormous. In 1790, before the passage of the act there was less than one newspaper produced for every 5 citizens. By 1840 there were almost three papers printed per person.

The Gilded Age

The Gilded Age, generally defined as the period following the Civil War, although more specifically between the election of Rutherford Hayes and the end of reconstruction in 1976 and the Panic of 1893, was a time of immense development in American history. The economic scars of the Civil War had started to heal, even though the social scars were still visible. The economy grew dramatically due to the effects of industrialization and new forms of economic organization, and immigration increased from Eastern Europe, creating a strong trend toward urbanization and diversification.

The Gilded Age was also a period of immense graft and corruption, a theme that would be a mainstay of journalistic reporting throughout the era. The federal bureaucracy became ever more clogged with political appointees in sinecures, expanding the spoils system that was the hallmark of the earlier Andrew Jackson administration in the 1830s. Furthermore, political machines drove the politics of major metropolitan cities, and used a system of corruption to ensure the election of desired candidates.

Newspapers would play a crucial role in exposing scandals and investigating the wrongdoing of public officials. However, the ethos of journalism of the time was very different from journalism in the modern era. Newspapers commonly took strong political stances, which was reflected in their reporting. Major newspapers were associated with one of the political parties or a particular social movement. Scandals, therefore, were often unearthed by journalists opposed to the policies of a particular politician.

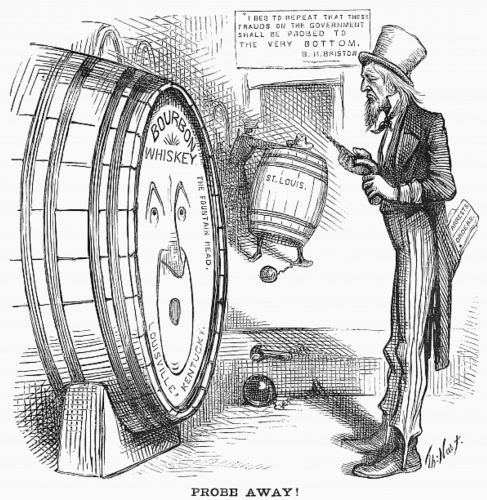

The presidential administration of Ulysses S. Grant is widely considered one of the most corrupt in history, although Grant himself is often considered a more minor player in the on-going scandals that plagued his time in office. There were more than a dozen notable scandals during his administration, but this article will focus on a representative case in this report: the Whiskey Ring.

The Whiskey Ring (1875) was a tax evasion scheme developed by the newly-empowered liberal Republican political machine in Missouri. The schemers bribed and cajoled administrators in every phase of the production of whiskey to underreport their numbers to avoid paying the whiskey tax – and therefore significantly increasing their profits. The money was then diverted to the local political machine, to increase its power over potential rivals.

The scandal was revealed in a series of investigations by Myron Colony, the commercial editor of the St. Louis Democrat, a paper opposed (perhaps obviously) to the Republican machine. Given his position, he was able to request figures from the different stages of the whiskey production process, eventually discovering the fraud when he reconciled the numbers. The story received immediate attention from across the country, and helped to usher in the end of reconstruction following the 1876 election.

The Whiskey Ring was not the most notable scandal in the immediate post-Civil War period, a title that is generally given to the enormous Crédit Mobilier scandal. Here, the U.S. Congress approved funds designated to the Union Pacific Railroad to build the first transcontinental railroad, but the funds were partially diverted to the Crédit Mobilier company and also used to bribe congressmen. Almost $50 million in funds were profited, an amount today that equals around $700 million after adjusting for inflation.

Newspapers played a crucial role in exposing the scandal. The Sun, a conservative newspaper in New York, received information about the diverted funds and the central role that congressman Oakes Ames took in the scam’s design. The newspaper was opposed to the reelection of Grant as president in 1972, and used the scandal to target him and his administration in reports throughout the election (Grant was uninvolved in the scandal himself).

The level of corruption in national politics was perhaps moderate compared to the political machines that controlled the major urban areas of the country. No machine was more notorious than Tammany Hall, which controlled New York City politics for more than a century, and particularly under William Tweed in the post-Civil War period.

Newspapers reported the lurid details of the corruption and graft, but it was the political cartoons drawn by Thomas Nast that were permanently etched in the minds of citizens. Nast, a Republican and a cartoonist for Harper’s Weekly, was deeply disturbed at the level of corruption in the Tweed administration and began a campaign to discredit him. His caricatures of Tweed are very famous in American history, and the attacks discredited Tweed, who eventually lost an election and was later indicted.

Newspapers throughout this era, while staunchly partisan, were important fora to communicate prominent issues to the public. The enormous corruption provided instant fodder for the press, but it also ensured that newspapers and journalists upheld the ideals of the fourth estate – to question government and to keep it accountable.

Progressive Era to Modern Era

The Progressive Era was marked by a reconsideration of the excesses of the Gilded Age. The changing nature of the American economy due to industrialization had placed a high toll on citizens, and its effects were more fully realized at the turn of the twentieth century. Progressive reformers like Robert LaFolette led the demand for new labor laws, increased antitrust enforcement, a new environmentalism and the push for women’s suffrage.

As they did throughout the Gilded Age, newspapers would continue to play an instrumental role in affecting the course of the public’s debate on major issues. Perhaps no issue shows the power of the press at the time better than the issue of the USS Maine.

The USS Maine was a navy battleship stationed in Havana harbor to stand watch over the Cuban revolution against Spain. For reasons that remain unclear, it sank in 1898, and news quickly reached America. Newspaper editors, most notably William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer, began an aggressive campaign to push for U.S. intervention in the conflict. They continuously sensationalized the story, an approach that came to be known as yellow journalism that was designed to increased newspaper sales. Hearst would encourage other interventions outside of Cuba, including in Puerto Rico and in the Philippines.

However, the Progressive Era is more often known for its domestic reforms, many of which were spearheaded by intrepid reporters who brought attention to the damage created by the excesses of the Gilded Age. Ida Tarbell is perhaps the most famous reporter of this era, reinventing the notions of investigative reporting with her lurid tales of the rise of the Stanford Oil Company and the dangers to the public of the oil trust. The sensational tale, which was serialized in McClure’s, gave impetus to Roosevelt to increase his anti-trust policies.

However, it was not just classical journalism that brought the public’s attention, but literature published in newspapers as well. Upton Sinclair wrote about the meatpacking industry in the The Jungle, in which he follows the travails of an Eastern European immigrant family in Chicago. The novel was originally published in the socialist Appeal to Reason newspaper, and while not its original goal, led to significant reform of food and drug laws in 1906.

Newspapers and print journalism would be a mainstay throughout the century, but changing technology would damage its monopoly over the dissemination of information. The development of radio provided broadcasts for the first time in America, and World War I created a need for a nationwide broadcast system that would lay the ground for this new source of news. The medium was a popular choice of Franklin Delano Roosevelt in his fireside chats, and came to be one of the trusted sources of news in America.

However, it was the development of television that proved to be most significant in the fate of newspapers. Broadcast television offered something that radio and newspapers could not: live video, and it was this ability that drew audiences to the new medium. The major radio corporations moved their operations to the television, creating evening news broadcasts that became a top source of news in the 1950s.

Major news stories, such as Nikita Khruschev’s visit to the United States in 1959 and the downing of a U-2 bomber with Francis Gary Powers on board were broadcast over the television, although newspapers were still a key part of the media. The assassination of John F. Kennedy in 1963 demonstrated the power of television to provide information faster than newspapers, but they continued to provide further details that couldn’t fit on the evening broadcasts.

This division between the immediate and visual on the television and the detailed and lengthy in newspapers was clearly seen in the Vietnam War. Television cameras broadcasted live from the war zone for the first time, allowing everyday Americans to see the vagaries and horrors of war up-close, increasing war weariness. The social effect of these reports is dramatically different from the yellow journalism that encouraged the Spanish-American war at the turn of the century.

However, newspapers were still in the driver’s seat for journalists. The release of the Pentagon Papers in 1971 created a national sensation about the Johnson administration’s knowledge about the war in Vietnam, and the details were released by The New York Times in a series of articles. Just a few years later, President Richard Nixon would resign after an investigation by Carl Woodward and Bob Bernstein of The Washington Post demonstrated Nixon’s involvement in the Watergate break-in.

Newspapers were pivotal in building up reform movements and holding politicians accountable throughout this era. The fourth estate was alive and very healthy, but the development of new mediums for communication would quickly change the economic models of the media leading to questions about how this unofficial branch of government was holding up.

Cable News and the Internet

Newspapers reached a theoretical height of excellence in the early 1970s – never before had a president of the United States resigned in scandal, and the investigation was conducted almost entirely by newspaper journalists. However, the velocity of news would increase dramatically with the development of new mediums including cable news and the internet, and newspapers faced increasingly stiff competition in their basic business.

The Cable News Network (now known as CNN) was first broadcast in 1980, and provided a 24-hour medium for constant news. The channel suffered from credibility issues throughout its first decade of operations, and proved to be mostly insignificant against the already established evening news television broadcasts and newspapers.

That dynamic changed in the First Gulf War. When the bombing of Baghdad by coalition forces first began, CNN had the only reporters in the city and broadcast the bombing live. The vivid coverage drew wide attention among the public, and put CNN “on the map.” The development of popular primetime shows like Larry King Live and the Capitol Gang helped to cement the network’s ratings and prominence.

However, it was the development of the internet that proved to have the most immediate effects on the print media industry. The internet was opened to commercial traffic in 1995, and newspapers quickly joined the new medium. The world wide web may now appear revolutionary, and indeed, commentary certainly was enthusiastic at the prospects for the new medium. However, the power of the internet to deliver the news was not convincingly clear until 1998.

One of the most sensational stories of the 1990s was the scandal of Bill Clinton and Monica Lewinsky. The story was first investigated by Newsweek, which had learned that Lewinsky owned a blue dress with the stain of the president on it. While reporters for the magazine waited for further sourcing, the news of the dress was scooped by Matt Drudge of the Drudge Report, an online clearinghouse of news headlines with a conservative slant. Journalists of all stripes learned that methodical sourcing and getting the story right was no longer the dominant ethos of the industry.

The internet is merely a tool to connect people together, but it was the development of new modes of communication that would truly revolutionize the dissemination of news. Web logs, later known as blogs, became an immensely popular way for everyday citizens to update the world about their lives and news – democratizing the news reporting function outside of the small elite of journalists that had previously controlled the media. These blogs linked to articles and provided immediate opinions and analysis, and represented an entirely new way to report on news than previously seen.

In the past few years, the development of social networking sites like Twitter and Facebook have connected people like never before, and ushered in the era of social media. Articles today are increasingly coming from diverse locations and spread by the recommendations of one’s friends. These changes have fundamentally altered the nature of the newspaper industry, representing something of a paradigm shift in how journalists have traditionally functioned.

Today, there are significant debates over the effect of the internet on the knowledge of everyday citizens and whether new sources of journalism are meeting their fourth estate obligations. Answering those questions is difficult, but it is important to remember the limited time frame that analysts have to look at the history of the internet. Social networking has only developed in the last few years, and its effects are not even entirely clear. The internet is changing how we read the news, and that may be a tremendous positive, a negative, or perhaps a mixed bag.

Economics of Journalism

The newspaper business has been in decline for the past twenty years. Almost every single source of revenue, from newsstand and subscription sales to classified and retail advertising has fallen dramatically. This has led to the bankrupt reorganizations of a number of very prominent national newspapers. The Washington Post, The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal all fired hundreds of journalists and staffers in 2009 in an effort to reduce costs. Even these efforts have not been enough to restore healthy profits, The New York Times reported a 26% drop in year-to-date profits in the fourth quarter of 2010.

The forces driving these trends are complex, but the basic cause is that the newspaper business is organized around a model that was extremely profitable when newspapers were the only medium to receive news, but extremely vulnerable in the face of competition.

News as a product has two important economic features. First, news is non-excludable, meaning that once the news is reported anyone can use it. Second, while it is expensive to pay reporters to gather information, the costs of actually distributing this information is the same regardless of how much information is actually produced.

Before television became a regular source of news, newspapers had a loophole in the non-excludability condition of news. While a newspaper could not prevent a competitor from reporting on a breaking news story once it had published an issue, the lag of a single day was enough to make breaking a story before another newspaper a very profitable activity.

Moreover, because distribution costs were the same regardless of how much information each paper collected, there was a tendency toward monopoly once a big paper had set up a sufficient distribution network. The fixed costs of distributing information had another side effect; newspapers became an extremely effective way to distribute classified ads because the marginal cost of including them in the paper was so low. Similarly, it became extremely profitable to include advertising in the paper since the additional cost of including ads was so low. Classified and retail advertising still accounts for 80% of the revenues in the newspaper business.

The rise of the Internet and cable news has completely transformed this economic situation. No longer could newspapers expect to be the biggest beneficiaries from reporting a story. As soon as an outfit like The New York Times reports a new story, cable news networks and bloggers can move quickly to cover the story – with much of the profit of the hard work of newspaper reporters going to other players. This is one the primary drivers behind the trend that there are now less than .5 newspapers per household in the United States, fewer than there were in the 1800s.

Furthermore, classifieds can be handled much more effectively through online services and newspaper advertisers began being lured away by Internet ad networks, which promised contextual ad targeting. Thus, both circulation and revenue have fallen off of a cliff in recent years. Circulation has fallen by more than a third since the mid-nineties while ad-revenue per circulation has fallen by 20% in the last ten years. The result has been an industry that has seen its revenues fall by half.

The newspaper business is in decline, but there is now far more news available to interested parties than there has been at any time in our nations history. The Internet has enabled citizen journalism to an extent that was never before thought possible.

The Internet has enabled disintermediation in many industries. Travel agencies and bookstores have been replaced by websites that cut the middlemen. Something similar is happening in news, where many journalists build a following of people that will read their work regardless of where it is published. For this reason, sites like The Huffington Post prominently display pictures of their columnists, whereas bylines in The New York Times are very small.

News companies are worried because the average time that a user of a news website spends any given day is only a fifth of what they might spend reading the paper. However, this is because consumers of news no longer pick just one paper, instead they hop around to wherever they find information they want or journalists they like. Given the possibility for access to news from the workplace and mobile devices, consumers may actually spend more time reading the news today than they did ten years ago. Given the superiority of ad targeting on the Internet compared to physical space, the overall ad revenues from news might go up, though likely much of the benefit will go to reporters instead of the papers.

For these reasons we do not need to fear too much the journalism will disappear. The form will change radically over the next few years. However, the result will likely be far more content, available to far more people.

Effects of the Internet

Overview

Since its conception in the 1950s, the developers of the internet had always intended for it to become a hub of communication, information storage and society itself. The original pioneer of the internet was J.C.R. Licklider who envisioned, “A ‘thinking center’ that will incorporate the functions of present-day libraries together with anticipated advances in information storage and retrieval and the symbiotic functions suggested earlier in this paper. The picture readily enlarges itself into a network of such centers, connected to one another by wide-band communication lines and to individual users by leased-wire services.”

It is a vision startlingly similar to the modern internet’s structure. While the internet’s pioneers readily anticipated the technical challenges and goals of their invention, the social, economic and cultural impacts were far less discernible. The internet created giant companies like Google and Facebook who embraced the new medium, and decimated old economic pillars like the recording industry that failed to change. However, many industries are still in the process of adapting to the internet and face immense hurdles as they attempt to survive in the 21st century.

Nobody knows this better than journalists. Over the past decade, newspapers, once the pillars of journalism, have been losing readership and revenue, and according to the American Society of News Editors employment in the country’s newsrooms has fallen by 15% just during the 2007-2009 period. This decline does not, however, mark the end of news and journalism, the Economist writes, “As large branches of the industry wither, new shoots are rising. The result is a business that is smaller and less profitable, but also more efficient and innovative.” Journalism as a whole still remains relevant and necessary for the masses, but it is also an industry that is now open to change and dramatic shifts in power and influence.

Time-Displacement and Efficiency

Perhaps the best way to articulate the changes in the news industry is to look at how news readership has changed over the past decade. As this chart from the Economist shows, newspapers and TV have undergone a slight decline in readership over the past decade while the Internet has dramatically spread as a source of news. However, the more important thing to observe from this chart is that the overall percentage of news sources used has increased. In 2001, the total percentage of TV, newspaper and Internet was around 135% while in 2008 it had increased to 145%. This observation brings up the two competing hypotheses regarding the internet’s effect on overall news readership.

The Time-Displacement Hypothesis is based on the idea that time is zero-sum. As Lars Willnat explains it, “Because there are only 24 hours in a day, time spent on one activity must be traded off against time spent on other activities.” On the other hand the Efficiency Hypothesis argues that the internet increases efficiency so users have more time for other activities, and that technologically advanced individuals tend to be able to multitask and fit more activities into less time. Thus the internet actually supplements news readership instead of reducing it.

A number of preliminary studies showed that increased time spent on the internet reduced a number of other activities including television viewing and face-to-face social interactions. Later studies have shown that the internet doesn’t actually impact daily activities, and that it has a positive impact on newspaper reading and radio news listening. Perhaps the most important aspect of these studies is how they control for different demographics. The original study supporting Time-Displacement had no controls unlike other studies supporting the Efficiency hypothesis.

Lars Willnat’s study used a number of controls on age, gender, ethnicity and income that were gleaned from earlier less extensive studies and he came to the conclusion that, “Internet news usage is not associated with the time spent using traditional news source,” and that, “Internet news usage does not compete with traditional news consumption in a zero-sum time scenario, as has been suggested by some earlier studies.”

Revenue vs. Readership

The debate over the internet’s effect on traditional news readership remains open, but it is certain that overall news readership has increased over the past ten years. Unfortunately the other certainty in the news industry is that overall revenue has decreased even as online readership increases, as shown by this chart from the economist. While the decrease in revenue during 2007 and 2008 might be blamed on the recession, the Economist notes that, “Online advertising money has moved to search—ie, Google—and excess supply has depressed prices of display advertisements.”

Despite this decrease in revenue there exist a number of specialist online outfits that have remained profitable by charging readers money. The two most mentioned organizations are The Financial Times and The Wall Street Journal, both of which require payment for those who wish to view more than a certain number of articles per month.

There is one more statistic that bears mentioning. It comes from the Pew Centre’s poll on media usage which found that over the past decade the number of 18-24 year olds who received no news at all via any medium rose from 25% to 34% over the past decade. This alarming decrease indicates that the internet might not be to blame for decreased revenue, rather an increasing disinterest in news from today’s youth is diminishing the overall readership base for all forms of news.

How Has Journalism Changed?

Like the printing press, the telegraph, television and all other forms of media that came before it, the internet has not only changed the methods and purpose of journalism, but also people’s perceptions of news media. Professors Bardoel and Deuze note that, “the shifting balance of power between journalism and its [audience], and the rise of a more self-conscious and better educated audience (both as producers and consumers of content)” has indelibly altered the landscape of journalism.

The two largest changes in modern journalism strike at the heart of traditional notions surrounding journalists and news companies. Firstly, the rise of the blogger and user-based journalism has become immensely popular among both new and old media companies, a change that has drastically altered the definition of a journalist. Secondly, the linked nature of the internet has given rise to content aggregators like Google news or The Huffington Post that no longer rely on individual journalists to provide news, but instead depend on their ability to gather and collect information into a single location where users can access it. Together they are altering society’s traditional ideas regarding journalists and news.

Further Reading

- McChesney, R. W., & Nichols, J. (2010). The Death and Life of American Journalism: The Media Revolution that Will Begin the World Again (1st ed.). Nation Books.

- Carlyle, T. (1966). On Heroes, Hero-Worship and the Heroic in History (6th ed.). University of Nebraska Press.

- Harcup, T. (2006). The Ethical Journalist (New edition.). Sage Publications Ltd.

- O’Reilly, T. (2007). What is Web 2.0: Design patterns and business models for the next generation of software. Communications and Strategies, 65, 17.

- Ed. Paterson, Chris and David Domingo (2008). Making Online News. Peter Lang Publishing, Inc.

- King, Elliot (2010). Free for All: The Internet’s Transformation of Journalism. Northwestern University Press.

- PBS. (n.d.). Charlie Rose – Emanuel Cleaver, Laura Richardson, Arianna Huffington, Thomas Curley, Robert Morgenthau.

- Clifford, S. (2009, April 8). Magazines Blur Line Between Ad and Article. The New York Times.

- Tuchman, G. (1973). Making news by doing work: Routinizing the unexpected. The American Journal of Sociology, 79(1), 110–131.

- Bromley, R. V., & Bowles, D. (1995). Impact of Internet on Use of Traditional News Media. Newspaper Research Journal, 16(2), 14-27.

- Willnat, L. (n.d.). The Impact of Internet News Consumption on Mass Media Use. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Communication Association, Dresden International Congress Centre, Dresden, Germany.

- Stoneman, P. (2008). Exploring Time Use. Information, Communication & Society, 11(5), 617–639.

- Federal Trade Commission (June 15th 2010). Potential Policy Recommendations to Support the Reinvention of Journalism.

Originally published by Stanford Computer Science, Stanford University, free and open access, republished for educational, non-commercial purposes.