Wikimedia Commons

By Dr. Jürgen Wilke

Professor of Journalism and Communications

Johannes Gutenberg University

Translated by: Christopher Reid

Editor: Jürgen Wilke

Copy Editor: Christina Müller

Abstract

Journalism refers to the system of procuring and disseminating the contents of modern media of mass communication. Those who exercise this function are called journalists. The historical beginnings of journalism can be ascribed different dates, depending on the definition. Its development, nonetheless, went through several phases: After a “pre-journalistic” phase, it is possible (in Germany) to speak of “correspondence”, “literary”, and “editorial” journalism. The journalistic profession initially underwent a similar development in other European countries, until separate traditions formed in the 18th century. Anglo-Saxon journalism in particular went into different directions than the “literary” journalism of the continental European countries. This further involved different types of editorial organisation. In the second half of the 19th century, journalism started to become professionalized, which further led to the emergence of journalistic and professional associations and initiatives for journalism education.

Terminology, Periodisation, and General Framework

Le Journal des Sçavans, 1665, BnF Gallica.

Europe is the birthplace of journalism. This is not only true for the concept, but also for journalism as a practice. The term is of French origin and derived from the word for “day” (“jour”). It came into use as a result of the French Revolution in 1789, as the printed press became a forum for shaping opinion,1 and was also commonly referred to in the 19th century in other European countries. The job description “journalist” was used even before this, however. Its first usage appears to have been in reference to the founders of the Journal of Sçavans, the world’s first academic journal founded in Paris in 1665 . The job description was known in England from the beginning of the 18th century.2 It was not until the end of the 18th century that the term “journalist” acquired its more general meaning and gradually replaced older designations such as the term “Zeitungsschreiber” (“newspaper writer”; also: “Avisen-Schreiber” [“notices writer”]) in Germany or “novellante” in Italian. The terms “journalism” and “journalist” are now commonplace in many European languages, not only in French (“journalisme”) and English (“journalism”), but also in German (“Journalismus”), Italian (“giornalismo”), Portuguese (“jornalismo”) and Czech (“žurnalismus”). An exception is the Spanish “periodismo”, in which the regularity of the performed function constitutes the essence of the activity.

Just when and where one identifies the beginning of the history of journalism depends on the definition of the term. If journalism is considered to be an “Anglo-American invention” and a “field of discursive production” with its own norms, such as objectivity and neutrality,3 it can be dated to the second half of the 19th century. Others see the “birth” of the journalist in 18th-century Germany, which is associated with enlightenment and the flourishing of journal publishing.4 In both cases, however, it is usually only mentioned in passing that journalistic tasks like the targeted procurement and processing of news items in fact go back much further. One can thus say that the history of the profession began with a “pre-journalistic” period and identify three additional developmental phases involving the transformation of journalism’s basic functions: “correspondence”, “literary”, and “editorial” journalism (see below).5 A system-theoretical determination of functions can also serve to further divide up the history of the journalist profession in Germany, which can similarly be broken into four phases of varying length: “genesis” (1605–1848), “formation” (1849–1873), “differentiation” (1874–1900), and the “breakthrough of modern journalism” (1900–1914).6 Such long-term periodisation is not established for other countries, although for France the foundation phase (“fondation”) of modern journalism is dated from 1880 to 1918, followed by a construction phase (“construction”) from 1914 to 1940 and a reconstruction phase (“reconstruction”) until 1950.7

The cultural diversity of Europe makes it difficult to provide a coherent description of the history of journalism on the continent. Due to the particular historical circumstances and linguistic borders, this activity developed mainly in a national context, although its material (news) also had transnational character. A national approach is also found in research, which is primarily concerned with the history of the press (and later other media) and has focused less on the history of journalism as a professional practice.8 There are thus mostly national historical accounts of the history of the press such as for England,9 France,10 Germany,11 Italy,12 and Spain,13 while comparative and transnational compendia or studies so far have been exceptions.14 Despite national differences, there are nonetheless similar developments in the history of journalism in Europe. There have also been reciprocal influences between countries, including those from outside Europe and the United States in particular. These influences, however, were partially asynchronous and showed distinctive dynamics.

The Pre-History of Journalism

The basic substance of journalism is broadly understood to be a shared piece of information – not private information, but rather information that satisfies some social and public interest. This activity accordingly existed even before the technological means were present for the latter’s dissemination. One can therefore certainly speak of a “pre-journalistic” phase in the history of this activity.15 Human interest in news is socially motivated and was already satisfied by certain individuals in the Middle Ages. Singers and minstrels moved from place to place and depicted events that they had seen or learned about. For this reason, they were called “wandering journalists”.16 Similar functions were fulfilled in England by the presentors of ballads and commemorative poems. Events were furthermore recorded in writing in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles from the 8th century, which can thus be considered a precursor of the press.17

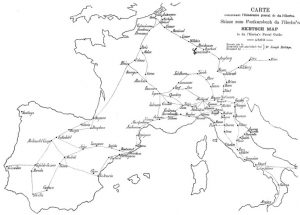

The systematic consolidation of the postal network in the early modern period accelerated communication within Europe and facilitated a change in the perception of the spatial structures of the continent. / Joseph Rübsam (1854–1927): European postal routes in 1563 according to the travelogue of Giovanni da L’Herba, sketch, in: L’Union postale, revue de l’Union Postale Universelle, Bern 1900, image source: Wikimedia Commons (Click Image to Enlarge)

Fuggerzeitung aus Rom vom 14. Oktober 1581; Österreichische Nationalbibliothek.

The desire for news grew in the early modern period with its expeditions and the spread of trade relations . Large trading houses cultivated extensive correspondence with their branch offices. In Europe, proper communication networks formed, which was made possible by the expansion of postal routes.18 Written messages, for instance, from the Fuggers’ Augsburg merchant house, still exist from the years 1568–1605 (so-called “Fugger newspapers”) .19 While they are not the only extant collection, they are the best known and the most important of their kind. Firm employees (factors) in the branch offices became reporters of the news, but so did agents, friends, and acquaintances. Use was also made of paid newspaper writers and “novellantes” (story tellers), like those first employed in Venice in the 16th century.

Nouvelles à la main 1748; BnF Gallica.

At that time, this Italian city and the Rialto in particular were centres of information exchange.20 It should therefore come as no surprise that this is where merchant letters gave rise to avvisi as early written news bulletins.21 In Venice, the news writers were called “reportisti” (in Rome “menanti” and Genoa “novellari”) and stood in dubious reputation: “Sie galten als unzuverlässig, gar unglaubwürdig und standen im Ruch der Spionage.”22 North of the Alps, the first known paid newspaper writers were in Augsburg in the 16th century. Philip Hainhofer (1578–1647) , for instance, opened an office there in the early 17th century, where news was transcribed and delivered to interested parties, mostly to princes.23 In France, nouvelles à la main also circulated, and continued to do so for some time afterwards because they remained outside of the supervision by the authorities.24

Journalism by Correspondents

The critical precondition for the development of journalism in Europe was the invention of the printing press in the middle of the 15th century by Johannes Gutenberg (ca. 1400–1468) in Mainz. Only then did the opportunity arise to reproduce and disseminate a large volume of information. Very quickly, people in Germany and elsewhere in Europe also began to print news. The publications had different names, but were quite similar in content and form.25 In Germany, they were called Newe Zeytungen, in the Netherlands courantes, in France canards, in England corantos, diurnalls, or news books, in Spain relaciones and in Portugal relaçãos. In Venice, they were printed under the name gazette. These single-print newspapers usually reported on political, military, and social events, but also on calamities and scandals.

The news was supplied to the printer by correspondents, who were in places where important events occurred or where information could be obtained from elsewhere. These correspondents thus in effect carried out a journalistic function, justifying the use of the term “correspondence journalism”.26 There were three main groups of active correspondents:27 first, officials and envoys, who were in residence or travelling on diplomatic missions; second, representatives who were based in other cities for their trading companies; and, third, humanist scholars , members of the universities and monasteries . These three groups were able to provide political, economic, cultural, as well as sensationalistic news.

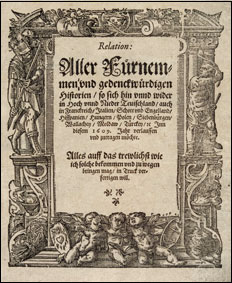

Relation 1609, UB Heidelberg.

A century (and more) passed before the Newen Zeytungen, corontos, news books, diurnalls etc. gave way to the periodical newspaper – the first mass medium of the modern era to come out at fixed regular intervals. As far as we can tell, this occurred for the first time after several intermediate stages in Strasbourg in 1605. Johann Carolus (1575–1634) , who had already duplicated and distributed handwritten news items there, started to print them up in a weekly newspaper (Relation ).28 The first recorded volume dates from 1609. A second German-language newspaper (Aviso) already appeared in the same year in Wolfenbüttel. This business model was so promising that newspapers were soon being printed in other cities. Elsewhere in Europe , however, it would take several years or decades for similar progress to be made.29

The newspapers of the 17th century (and for the most part of the 18th century) were very similar.30 With regard to their content, they offered soberly drafted reports, mostly on political and military events from different parts of Europe, which were supplied by resident (foreign) correspondents. “Correspondence” journalism thus initially predominated. It was not necessary to make a selection of the news because it remained scarce. Whenever possible, everything was printed that was available. Titles and headlines were not yet used. Reports were simply strung together with their localities and dates of origin.

At first, most printers could make do without having their own journalists. Only a few cases are known in the 17th century in which news was abridged, edited, and (linguistically) adapted by a specially qualified person. It was not until the 18th century that the flow of news reports was so great at certain locations that someone was needed to assume the on-going task of selecting and preparing the news for publication. Only large newspapers could afford to do this, however, that focused on providing original reporting rather than simply reprinting material from other papers. This latter method of publishing, in which “Schere und Kleister” (“cut and paste”) became a proverbial journalistic tool, occurred regularly due to a lack of content.

Hardly present at all in early newspapers were opinion articles. Correspondents did not want to impose their personal views on their readers, but rather inform them so that they could develop their own opinion. In essence, they considered themselves to be impartial and objective rapporteurs. This reluctance, however, was also due to the official press control, which sought to suppress unwanted information and opinions. The newspapers were aimed primarily at an educated readership that could be assumed to have the requisite knowledge for understanding their reporting. The circulations were still relatively low, amounting to little more than a few hundred copies.

The Emergence of Opinion Journalism

In the 18th century, the role of journalism in Europe began to change. For a variety of reasons, this process began in England. Because the British Parliament had not renewed the Printing Act in 1695, press freedom for all intents and purposes prevailed in the United Kingdom.31 As pre-censorship no longer existed, the newspapers were now able to become organs of public opinion. This was encouraged by the fact that England already had a Parliament where intense debates were the order of the day. Parliamentary reporting, however, continued to be regulated even after 1695. It was only tolerated after 1772.32

To publicly disseminate opinions and attitudes in the 16th century, there were already several print media available. In Germany, they were referred to as “Flugschriften”,33 in England as pamphlets.34 At the time of the Reformation and of the ensuing religious conflicts, they had unprecedented print runs (up to 4,000 copies per issue). They were usually written by the leaders of the religious and social movements themselves and therefore not actually products of journalism. In Europe’s purely Catholic countries, such pamphlets either appeared much less frequently or failed to find any fertile ground at all.

As a result of the repeal of the Printing Act, the number of newspapers in England rose rapidly. As a consequence, there was strong competition, which caused many papers to close up shop. At this stage, the newspapers began to distinguish themselves from continental papers, since they had more latitude in terms of both substance and style. At the beginning of the 18th century, however, there was still a division of roles: The printer was responsible for the news (along with the advertisements), whereas the authors themselves oversaw the essay section and other sundry contributions.35 They weren’t required to limit themselves to writing sober reports, but could also publish critical articles and voice their own opinion. It was helpful that a bipolar party system already existed in England with the Whigs and the Tories, resulting in the establishment of opposition newspapers. Nevertheless, journalism was rarely autonomous. Rather, as many papers were backed financially by the government, political parties or individual politicians, it frequently engaged in propaganda.36 Sustainable organs included the Daily Universal Register, which appeared for the first time in 1785. Three years later, it was renamed The Times, a newspaper that would become the flagship of independent British journalism.

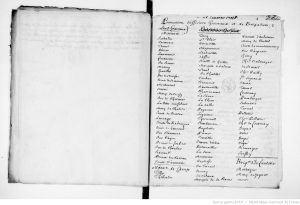

In the era of absolutism, the development of the press in France was limited by regulations. For a long period, the only real newspaper was the Gazette, founded in 1631. It appeared in Paris, but was reprinted in the provinces. From the 1660s, there were also scholarly, literary, philosophical, and entertaining journals. As already noted above, the Journal of Sçavans (from 1665) gave the publishers of such print media their particular job title. It is because of the diversity of these publications that more than 800 journalists can be identified in France from 1600 to 1789.37 Nonetheless, if we use our more restricted definition of journalism, then hardly more than a dozen journalists could be counted at this time. Such a large number is only reasonable if we subsume all individuals under the term “journalist” who during the examined period were involved with a press organ in any way (i.e. also printers and employees of all kinds).38

The outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789 led to an explosion of the press (and opinion journalism) in Paris, with the number of media outlets quickly going into the hundreds.39 Several prominent and radical revolutionaries were themselves active as journalists, including Camille Desmoulins (1760–1794) , Jean-Paul Marat (1743–1793) and Jacques-René Hébert (1757–1794) . Thanks to freedom of the press, ideologically and politically competing bodies could exist alongside each other, even those who continued to support the monarchy. The latter’s situation, however, changed with the imprisonment and execution of King Louis XVI (1754–1793) .

For the 18th century, it is possible to speak of a “literary” journalism and hence temporally denote the third phase of the history of the profession.40 Yet there were already earlier signs of this in the previous century in some leading newspaper and journals. The news was (no longer) at the centre of their activity, but rather its incorporation into larger narratives or extensive arguments. The authors were often examples of “Personen im beruflichen Zwischenraum zwischen einer akademischen Ausbildung und einer erhofften vollen Stelle im Sinne der neuzeitlichen Berufsverfassung.”41 Many authors in the 18th century tried to gain a foothold in the booming sector of journal publishing. While some only moonlighted in this field in addition to having another (principal) activity, the number of those who actually sought to establish (and financially support) themselves exclusively as freelance writers on the literary market increased.42

Wilhelm Ludwig Wekhrlin (1739–1792)

Evidence of a new understanding of the role of journalism can only be found in the late 18th century in Germany, especially for writers who were committed to the Enlightenment. One of these was Wilhelm Ludwig Wekhrlin (1739–1792) . His ideal was the journalist as a “public spy”, who not only wrote about the news, but also wanted to warn the public against false concepts.43 He also categorized the journalist as a “Sittenrichter” (“moralizer”) and “Advokat der Menschheit” (“advocate of humanity”) and thus anticipated modern role classifications. He can therefore be viewed as a proponent of “advocacy journalism”. In practice, however, as Wekhrlin’s example shows, it was still too difficult perform this role at the time.

Louise Otto-Peters (1819–1895)

Since its inception, the claim has been made that the press was the domain of men. This does not mean, however, that women had absolutely no role to play. One finds that women were already active in publishing the English news books of the Puritan Revolution.44 In Germany and in other countries, women in the 17th century and 18th century also often became owners of printing presses after their husbands had died and continued to run the company they had inherited. Female authors and editors are first encountered in the 18th century with journals that were directed primarily at female readers,45 but they were not active in the political press until later. In Germany, Louise Otto-Peters (1819–1895) published the Frauen-Zeitung (“Women Paper”), which can be considered an early organ of the women’s movement , after the revolution of 1848.46 The women’s movement, however, tended to find its particular forum in the following decades in journals.47 In England, women were already involved to a much greater extent in the journalistic profession from the mid-19th century, representing a “feminine”, even feminist journalism.48

Commercialisation in the 19th Century

In the early 19th century, and even long after this in some countries, journalism in Europe still suffered under official control or relied on government subsidies. Renewed suppression at the beginning of the century was initiated by Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821) , who not only kept a short leash on the press, but also excelled journalistically himself as a writer of bulletins.49 While his influence also resulted in a depletion of the press in other countries, it helped at the same time to unleash counter forces. When he was compelled to relinquish power in 1815, a golden age for the press and journalism seemed imminent. This again was short-lived. In the German Confederation, strict censorship was enacted in 1819 (the “Carlsbad Decrees”) for three decades, and in France itself, the return of the Bourbon monarchy led to restoration. With the July Revolution of 1830 , the number of opposition publications increased, despite repeated attempts to restrict their freedom.

Due to financial constraints, however, the press did not have much room to manoeuvre. Initially, political newspapers were required to finance themselves almost exclusively from their retail price. The income that was generated was frequently insufficient, which led to a reliance on donors and corruption among journalists. In the 18th century, advertisements were almost exclusively published in their own organs such as the advertisers in England, the Intelligenzblätter in Germany and the affiches in France. Only after a loosening of the state monopoly on advertising (in Prussia not until 1850) and the abolition of the advertisement tax (in England in 1855, in Germany in 1874) could the press in these countries fully commercialise. In the United States, by contrast, publishers had already created the mass popular newspaper (“penny press”) in the 1830s, which came up with completely different content than what had been offered previously in the still-dominant party press.

This American model was first followed in France. Two newspapers from the so-called presse à bon marché appeared immediately in 1836: Émile de Girardin’s (1806–1881) La Presse and Armand Dutacq’s (1810–1856) Le Siècle. Both papers made the advertising section the main source of funding, making it possible to reduce the retail price and to achieve a more profitable mass distribution. Political opinion had by no means been omitted, but the attempt to appeal to a larger readership was made by expanding the feuilleton as well as through gossip- and fashion-related subjects . This called for a different type of journalist: He was no longer someone who ultimately sought political office, as had often been the case, but someone who met the expectations of the audience.50

This image depicts the suicide of the French General Georges (1837–1891) at the grave of his beloved in the cemetery of Ixelles (Belgium). / Le Petit Journal, Le Suicide du Général Boulanger au cimetière d’Ixelles, cover, 10 October 1891, unknown artist; image source: Wikimedia Commons

Le Petit Journal (established in 1862), which cost only half as much as La Presse, became the most successful newspaper in France in the late 19th century. The content was largely geared toward the transmission of practical knowledge, news from everyday life, particularly miscellany (so-called “faits divers”) and novels, i.e. the “roman-feuilleton”. After two years, the newspaper already had a print run of 260,000 copies. In 1887, it was one million, which explains why the founding of the Petit Journal is thought to signify the birth of modern journalism in France.51 It also ushered in a new genre of journalistic (and literary) reportage. One even speaks of an era of “great reporters” (“grands reporters”) after 1880, whereby this role is generally viewed in combination with that of the man of letters.52

Beginning in the 1850s, popular dailies also became familiar in the UK.53 The catalyst behind this was the abolition of the stamp duty in 1855. The first daily newspaper was the Daily Telegraph and Courier in the same year, which was able to boost its circulation to 250,000 copies by 1880. Several other cheap mass newspapers were founded around the turn of the century such as the Daily Mail (1896), the Daily Express (1900), and the Daily Mirror (1903). Their heyday was a product of industrialisation which allowed the working class to join the reading public. In contrast, continental Europe initially remained underdeveloped.54

The commercialisation of the press began later on in Germany because it still lacked the necessary economic conditions. A party press also emerged in the wake of the revolution in 1848 which, however, did not thrive until after the unification in 1871 and the creation of a national parliament. Party newspapers were forums for opinion journalism, as the journalists themselves were often party members. Journalism and political activity thus frequently went hand in hand. This is especially true for the social democratic press, which recruited staff from its own party and the working class .55

The 1870s, however, also mark the beginnings of the mass newspaper in Germany. The distinctive type of newspaper that was established at this time was the “General-Anzeiger”. It was also largely financed with advertisements and strove to gain a wide readership, especially through local reporting and by ignoring political and religious controversies. Moreover, a lot of space was dedicated to material designed to entertain the reader. “General-Anzeiger” newspapers appeared in Berlin (Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger) and other major cities of the Reich. They achieved runs from 100,000 to 200,000 copies, which had previously not existed in Germany.In the 19th century, the American journalistic model made its impact felt, especially in the UK, so that people did speak of the “Anglo-American concept”.56 Later, American journalistic practices spread to other European countries as well.57 The term “Americanisation”, however, increasingly acquired a negative connotation, as it came to signify a threat to one’s own (journalistic) culture and was thus condemned. Germany, in any case, experienced a “verspätete Modernisierung” (“belated modernisation “) in the field of journalism,58 which the American writer Mark Twain (1835–1910) also commented on sarcastically at the beginning of the 1880s.59

The Professionalisation of Journalism

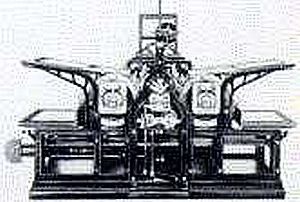

The Thüringen printer Friedrich Koenig (1774–1833) invented a steam-powered cylinder press in the early 19th century, which replaced the formerly standard hand presses in the printing industry. With the new cylinder presses, about 800 pages could be printed in the hour, allowing for a faster dissemination of larger circulations. Koenig’s Schnellpresse was used from 1814 to print the London Times. / Friedrich Koenig (1774–1833), cylinder printing machine, black-and-white photograph, undated, unknown photographer; source: AMI-Associação Museu da Imprensa.

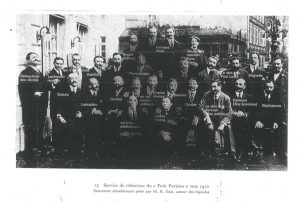

Service de rédaction du “Petit Parisien” vers 1910, black-and-white photograph, ca. 1910, unknown photographer, captions: M.R. Gast, in: Amaury, Francine La Société du Petit Parisien; entreprise de presse, d’éditions et de messageries, Paris, 1972, p. 642. © Presses Universitaires de France.

European journalism was professionalised in the second half of the 19th century.60 The need for journalists had already increased, as the press by this point had expanded in several ways. A main driver for this was innovations in printing technology . The number of titles grew considerably, the formats were larger, and the number of pages swelled. The content was also more diverse. Around mid-century, readers had thirty to sixty times as much to read in each newspaper edition as they had done two centuries earlier.61 The procurement and processing of this material required an increasing number of journalists, especially as the newspaper pages now began to print “lead stories” by dividing up content and providing articles with titles and headlines. This particular task accordingly became part of the journalist’s job description. The differentiation of newspaper content was also accompanied by specialisation in the journalistic profession . Besides the political editor, there was the trade and feuilleton editor, the (theatre) critic, and the court reporter. There were also editors for local news and, later, sports .

In Germany, the long tradition of anonymity in journalism was debated.62 While its proponents justified it as an expression of the “collectivism” of newspaper production, its opponents argued against the lack of transparency and accountability. In England, this latter principle was tied to the system of representative government. Wherever freedom of the press was implemented, it further entailed the (legal) requirement of attribution. This rule was established in France as well in 1850. The principle of anonymity corresponded to limited copyright protection for press content: Without an explicit reservation of rights, articles could be released for reprint. Only academic , technical, and entertaining journalistic content was protected. Miscellaneous news and daily reports could always be appropriated by other publications.

Before 1848, the number of journalists in Germany is estimated to have been about 400; by the end of the century, there were probably 2,500,63 and, by 1906, already around 4,600. Contrary to long-held assumptions, (German) journalists in the 19th century were highly educated. This was already true for the earlier Vormärz period (before 1848).64 Moreover, there was an excess of university graduates and not enough positions in the government or the economy. This resulted in a lingering overpopulation of the literary market.65 After 1848, the journalistic profession thus attracted people who, for instance, for political reasons had no other job opportunities in society. While journalism represented a “way out” for some of them from personal predicaments and others resorted to the profession as “would-be writers”, for an increasing number it became a professional goal from the start.66 The situation was quite similar in other European countries. In England, journalists usually came from the lower strata of the middle class, but there were also quite a few among them with a university degree.67 In France and Italy, the boundaries between journalism and literature especially remained fluid.

Strictly speaking, journalism lacked the same preconditions for professionalizing that could be found in other forms of employment in modern society.68 In late 19th century Germany, however, it is already possible to detect an “informelle Professionalisierung” (“informal professionalisation” process) that accompanied journalism’s development into a major occupation, which was labelled “Verberuflichung” (“occupationalisation”).69 This is evidenced by associated norms, the recruitment of young professionals, and a related growing self-awareness. The advancement of professionalism is also shown by the emergence of state and professional organisations, as well as the incipient efforts at the turn of the 19th century to train journalists (see below).

Editorial Organisation

From the 17th century, newspapers were produced for some time without any need for journalists in the actual sense. Similarly, there was also no prerequisite for an editorial staff. Beginning in 19th century in Germany, the term “Redaktion” initially indicated “die Gruppe der Redakteure, die ein ‘Druckwerk’ leiten”; by the turn of the century, however, it also referred “gleichzeitig auf den Vorgang des Redigierens von Nachrichten, auf einen materiellen Raum, in dem Medieninhalte bearbeitet werden, und auf die Personengruppe, die als Redakteure Medieninhalte beschaffen, bearbeiten und koordinieren. Ort und soziale Praxis sind damit bereits begrifflich denkbar eng verbunden und bedingen sich gegenseitig.”70Actual work and living spaces had become necessary since the early 19th century in cases of individual employees taking over full-time editorial duties for the printer. It is known, for instance, that the building which the publisher Johann Friedrich Cotta (1764–1832) bought in Augsburg in 1823 contained dwellings for the editors of the Allgemeine Zeitung along with three editorial offices. Work and living spaces were right next to each other and close to the printing workshop so that one can speak of a kind of “home editorial office”.71 Since Cotta published several journalistic publications at his press, the first major press company in Germany, he was also the first to introduce a type of pool system in which employees collaborated on various titles.72 In this period of the “editorial journalism” phase, writers who were active in journalism often relinquished their independence (or lost their independence) and became employees of the publisher.73

Room for the Börsen-Courier Editorial Staff for Commerce, undated black-and-white photograph, unknown photographer, in: Killisch von Horn, Arnold (ed.): 75 Jahre Berliner Börsen-Zeitung, Berlin 1930, p. 47.

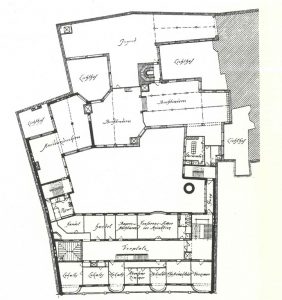

Floor plan of the Münchner Neueste Nachrichten building: second floor, drawing, 1906, creator unknown, in: Ministerium der öffentlichen Arbeiten (ed.): Zentralblatt der Bauverwaltung XXVI, 39 (1906), p. 247; source: Zentral- und Landesbibliothek Berlin.

Along with the expansion and substantive differentiation of newspapers (including the explosion of procurable material), the need for journalists and spaces where they could go about their work grew in the 19th century. At the same time, a typical editorial form emerged in Germany which corresponded to the segmentation of newspaper content into different departments or divisions . Doors along a corridor in the publisher’s building led to individual rooms where editors were stationed who were responsible for politics (which may have been further divided into sub-areas), commerce / trade, features and regional / local stories. The editor-in-chief had his own room. Beyond this, separate offices could be set aside for the library, editorial meetings, or for receiving visitors. After the introduction of new technologies at newspaper publishing houses, telephone and telegraphs were also on site.74

Since, in Germany, small newspapers with small printruns and limited scope were common, many operated with only one-person as editorial staff. In the early 1920s, publisher and sole editor were still often united in the same individual. One of the largest editorial teams at the end of the 19th century was that of the Berliner Lokal Anzeiger, after an increase in the number of journalists / editors from three (1883) to 46 (1899).75

Nellie Bly (actually Elizabeth Jane Cochran, 1864–1922) worked as a journalist for Joseph Pulitzer’s (1847–1911) New York World newspaper and travelled in this capacity from 1889 to 1890 in the footsteps of Jules Verne’s (1828–1905) novel Le Tour du monde en quatre-vingts jours (“Around the World in 80 Days”, 1873), becoming the first woman to travel alone through Europe to Hong Kong and Japan and, from there, back to the U.S. The roving-reporter type emerged in the Anglo-American journalism tradition, which makes a clear separation between the on-location reporter and the editor working in the office. / Nellie Bly (1864–1922), The New York World’s Correspondent who placed a Girdle Round the Earth in 72 Days, 6 Hours, and 11 Minutes, black-and-white photograph, ca. 1900, unknown photographer; source: New York Public Library

In England, too, printers for a long time lacked an editorial office (or news room, the term that was later established in the English language): “[J]ournalism was compiled and written on an ad hoc basis outside the print shop.”76 The responsibility of compiling the news was only gradually assumed by authors as a secondary occupation. The latter often wrote other types of journalistic articles, for instance, essays and literary contributions to weeklies , which described themselves in their titles as journals. Many newspapers also hired translators , who were in charge of the foreign press,77 or authors who kept an eye on local news and embodied the journalistic type of a “reporter”. This term, which would have a defining influence on Anglo-American journalism ,78 was first used in England in 1813.79 The function of the traveling (or “roving”) reporter was thus separated from that of the editor, who fulfilled internal editorial tasks.

This differentiation of roles was characteristic for British journalism, which did not assume its modern form until the end of the 19th century. Over the course of this process, the responsibilities of the editor were further spun off. This could only take place, however, with the expansion of the editorial staff.80 A critical factor in the division of labour in particular was the delegation of reporting, commentary, and design to different people. An exception to this was the tradition of German journalism that had developed since the 19th century. It was considered “holistic” because reporting and commentary often were penned by the same journalist. One has spoken here of “Rollenüberlappung” (“overlapping roles”). The belated guarantee of a freedom of the press and the structural conditions of the editorial organisation meant that the journalistic norm of the separation of news and opinion, which was the model in Anglo-American journalism, could not be entirely implemented in Germany.

The physical environments were also distinct: While the separation of the various departments was typical for Germany, in the UK (and the U.S.) there were shared rooms for editorial staff with desks for individual journalists. The typical French newspaper editorial offices of the 19th century (“salles de rédaction”) were dominated by a central table. There, individual journalists would sit down when they wrote or edited articles, and, according to contemporary accounts, were surrounded by a peculiar working environment.81

In the rest of Europe, there was evidence of an early separation of functions in journalism in Denmark.82 Scandinavia’s location on the northern edge of Europe made the press there depend on information from foreign newspapers, some of which was obtained in large quantity, translated and evaluated. From the 1880s, there was also an expansion of the press in these countries, and major (capital-city) newspapers were given their own buildings with (at first only a few) offices for journalists. At the turn of the century, their number at individual publications could still be counted on one hand. It more than doubled, however, in the following decades. News gathering and processing in the major cities of Scandinavia therefore was not too far behind that of London.

In southern Europe, however, the development of the press remained stunted until the end of the 19th century. In Spain, most newspapers had low circulations, often did not possess their own printing house, and, indeed, even lacked a professional editorial organisation.83 The first great modern newspapers emerged in the first decades of the 20th century. In the editorial staff of the newspaper ABC (founded in 1903), numerous jobs were initially isolated from each other. To improve the coordination of the different editorial tasks, however, a large communal table was soon set up in the centre. After some time, the growth of the newspaper and its publisher also led to a spatial differentiation of professional organisational functions. The newspaper El Sol, launched in 1917, quickly adopted the principles of Anglo-American journalism, separated out information and commentary, and strengthened the role of the editorial board.

Professional Journalistic Organisations

Over the course of the professionalisation process of journalism in Europe, professional journalistic organisations were also established to represent shared interests and help provide an identity to the members of the profession. In Germany, the beginnings of journalistic efforts of self-organisation date back to the 1830s and 1840s. The “Preß- und Vaterlandsverein” (founded in 1832/1833),84 the “Leipziger Literatenverein” (founded in 1842)85 and the Vienna journalists’ and writers association “Concordia” (founded in 1859)86 may be considered precursors.

The first attempts to establish a comprehensive organisation for journalists came out of the meetings for German journalists that had been held since 1864.87 The annual conferences dealt, among other things, with press legislation, pensions, job placements, or advertisements, and they passed resolutions directed at the government, employers (publishers), and the public. Due to federal decentralisation, professional journalistic organisations also emerged at the local level such as the “Verein Berliner Presse” in Berlin and the “Journalisten- und Schriftstellerverein” in Frankfurt. The “Verband deutscher Journalisten- und Schriftstellerverein” (VDJSV) founded in 1895 subsequently formed the first comprehensive and centralised professional organisation,88 which focused, among other things, on naming the authors of articles, the introduction of identification cards (journalist passes), shaping legislation and administrative measures, as well as provisions for welfare and insurance.

As valuable as this association was, it nevertheless did not meet the increasingly felt need for a proper vocational and professional body exclusively for journalists. This task was undertaken by the “Verein Deutscher Redakteure” (VDR).89 Its existence was accompanied by numerous controversies, however, which led to the group’s division.90 This suggests the significant differences that still prevailed in this field, along with the difficulty of overcoming particular interests and developing a collective identity. The “Reichsverband der Deutschen Presse” (RDP), an overarching professional organisation for journalists in Germany founded in 1910, was the first association to overcome these issues.91 It also represented the interests of journalists in the Weimar Republic,92 before being incorporated into the Third Reich’s system of state media control and exploited for propaganda purposes.

In the 19th century, professional journalistic organisations also emerged in many other European countries, and more followed after the turn of the century.93 There, too, the motives were the need for public recognition, to improve the fragile social situation for journalists, to stand up for the rights of journalists and press freedom and to reinforce journalists’ professional (self-) awareness. Frequently, local initiatives made their influence felt at the early stages.94

Soon, the very similar professional aspirations in different countries raised hopes of getting united on an international level.95 An inaugural meeting took place in London in 1893, with representatives from England, France and Belgium. A year later, there were already journalists’ organisations from 15 countries at a meeting in Antwerp. Members agreed to meet every year, passed bylaws, established a permanent office, and invited discussion on all possible material and moral questions relating to the journalistic profession. The Union internationale des associations de presse (UIAP) was then formally established in Budapest in 1896. In the following years, it expanded to other parts of the world and, before the First World War, included 100 journalists’ associations with some 18,000 journalists.96 At the annual meeting in Bern in 1902, a debate ensued over protecting journalists’ viewpoints when there are changes in newspaper ownership; three years later in Liege, the main concern was with editorial secrecy. There were calls for an international identification card for journalists. Overall, however, the record of the UIAP up until 1914 was rated poorly, as it was felt that the organisation’s resolutions had resulted in few concrete changes.97 However, there is also no lack of evidence suggesting the opposite.98

In order to overcome the deeply entrenched hostility stemming from the experiences of the First World War and to strengthen the community of shared interests, efforts were also made in the 1920s to improve international communication and cooperation in journalism. In 1926, French journalists launched the Fédération Internationale des Journalistes (FIJ), which was joined by numerous national journalist associations.99 Its aim was to help improve the material conditions of journalists, to strengthen their professional independence, and to elevate their moral standing. In addition, the FIJ’s goal was to promote the overall interests of the world’s press and to promote mutual understanding among journalists from different countries. One of its initiatives, for example, was an international court for journalists, which was established on October 1931 at the Peace Palace in The Hague. For all intents and purposes, however, it was already too late, as the circumstances fundamentally changed with the coming to power of the National Socialists in Germany. The FIJ, nonetheless, continued to exist in Paris and was not dissolved until after the invasion there of the German troops in 1940.

Journalism Education

To meet the growing demand for journalists since the 19th century, new groups of people now rushed into the occupation. This led to an overall decline in the education level. While 87.5 per cent of journalists in Germany had a university degree around the middle of the century, it was 78.5 per cent in 1900.100 It thus became more and more common that journalists entered their profession without training or at most with only practical instruction. Insofar as the level of education of journalists decreased and the profession attracted some dubious characters, the journalist, as sociologist Max Weber (1864–1920) famously put it, shares the fate “einer festen sozialen Klassifikation zu entbehren… und zu einer Art Paria-Kaste [zu gehören], die in der ‘Gesellschaft’ stets nach ihren ethisch tiefststehenden Repräsentanten sozial eingeschätzt wird.”101 Journalism thus stood in close proximity to the artistic world and Bohemianism. Parallel to this was the notion that journalism was a “profession of talent”, i.e. that it was a matter of individual talent that one was “born” with. This view hampered efforts for some time to develop a system of training for journalists.

Richard Wrede (1869–1932): Handbuch der Journalistik, Berlin 1902, scan: Jürgen Wilke. / Richard Jacobi: Das Buch der Berufe: Ein Führer und Berater bei der Berufswahl, vol. 8: Der Journalist, Hannover 1902, scan: Jürgen Wilke.

These precise circumstances, however, also gave rise to thoughts on providing a specific professional training for journalists. In Germany, the first rudimentary steps in this direction began in journalistic practice102 and the first attempts to incorporate the study of journalism into academic education were made around the turn of the century. The earliest traces of this are found at the University of Heidelberg, an attempt, however, that failed only a short time later. In 1916, Karl Bücher (1847–1930) , a former editor of the Frankfurter Zeitung and professor of economics, founded the Institut für Zeitungskunde at the University of Leipzig. He is consequently considered the father of modern journalism studies and its associated academic tradition of journalistic training.103 It remained difficult to implement such training in Germany, however. In the 1920s, there were little more than a handful of poorly equipped university institutes, as the main avenue into the journalistic profession continued to be a traineeship in editorial practices. For entirely obvious reasons, it was the Nazis who first identified the importance of training journalists.104

Opportunities for training journalists also were slow to emerge elsewhere in Europe. In Britain, the rule of “on-the-job training” was adhered to for an especially long time. The press there found that the practice of a profession was best suited to acquiring the necessary skills. The single exception to this rule was a two-year journalism course at King’s College at the University of London from 1922 to 1939.105 In France, the beginnings of journalistic training indeed go further back, but it also remained scarce.106 In Switzerland, the first journalistic seminars were organized in Zurich and Bern in 1903. The first course of instruction for journalism was devised in the Netherlands the following year, although it was not implemented until four years later.107 Structured curricula were not developed until after 1930. In the first decades of the 20th century, Spain undertook several short-lived initiatives for journalistic training. Among them, the most important were those from the Catholic newspaper El Debate, whose Institute of Journalism was heavily oriented toward American models. It lasted from 1926 until the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936.108 The new rulers set up their own institute in 1941, not only to train journalists, but also to control who had access to the profession. In Italy, which has a similar journalistic tradition to the one in France, training opportunities in journalism were dispensed with until as late as the 1970s.109

The United States is considered to be the country where the tradition of academic journalism training was first established. In 1908, the University of Missouri set up the first independent school of journalism,110 and with the support of the publisher Joseph Pulitzer (1847–1911) , teaching began at the school of journalism at Columbia University in New York in 1912. These institutions not only stand out because they were pioneers, but also because of their formal organisation, teaching programs, and trend-setting influence on numerous subsequent schools. This contributed to the professionalisation of American journalism, which was not approached in Europe until the beginning of the 20th century. The same is true for training in this occupation.

Between Political Instrumentalisation and Technical Innovation: Journalism in the 20th Century

On the one hand, the development of journalism in Europe in the 20th century was determined by constraints tied to the political situation and, on the other hand, by technological innovations that gave rise to new mass media. This, in turn, forced journalism to meet changing requirements.

The 20th century was marked historically by totalitarian regimes and two world wars. These factors either restricted the hard-won autonomy of journalists in the countries concerned or eliminated the journalists altogether. In Russia, where the liberalisation of the press after the death of Tsar Nicholas I (1796–1855) had started comparatively late anyway, the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 led to the establishment of a totalitarian communist system. Following the guidelines of Vladimir I. Lenin (1870–1924) , journalists had to fulfil the tasks of propaganda, agitation, and organisation111 and were thus demoted to being servants of the political elite. Journalism in the Soviet Union has therefore been referred to as an “antithesis of the Anglo-American news paradigm”.112

In the fascist dictatorships that were established in the 1920s in Italy113 and after 1933 in Germany, journalists were also expected to promote the dominant ideology and support the government’s objectives. Toward this end, the Nazis in particular built a sophisticated system for controlling the media in Germany. In addition to legal regulations and organisational measures, detailed instructions were also given to journalists on how they had to report and provide commentary.114

This photo from 1944 shows the editors of the Daily Mail in a typical Anglo-American journalism office: While most journalists had their own rooms in German editorial offices, British editorial staff sat in an open office that had both individual desks and a large conference table. / The Makings of a Modern Newspaper – the Production of ‘the Daily Mail’ in Wartime, London, UK, 1944, black-and-white photograph, photographer: Ministry of Information Photo Division Photographer; source: Imperial War Museum

Journalists were under especially strong pressure during the two world wars of the 20th century (1914–1918, 1939–1945). In general, the concerned countries again established censorship measures and tried to turn the press into a propaganda tool. Even in countries that maintained their democratic system of government, like England, official agencies had a mandate to exert influence on journalists . Journalists were supposed to advocate the country’s interests to the outside world and strengthen the morale of the citizenry at home. In France, after it had been captured by German troops in 1940, the press was largely censored by the occupying power. Journalism was divided into a chasm between collaboration and resistance.115

In the inter-war period in Germany (as in other European countries), conditions had indeed been formally established for a free and democratic journalism. This suffered, however, not only due to the consequences of war and economic difficulties. More than this, it found itself stuck in the centre of a bitter ideological conflict between the political extremes of the right (Nazis) and the left (communists). Nevertheless, the Weimar Republic produced outstanding journalistic achievements that remain models to this day.116

After the Second World War, both the overt and covert instrumentalisation of journalism was largely stopped in the democratic countries, all the more so because the environment for journalism had also changed. In the Western occupation zones of Germany, the victor nations sought to create the conditions for a free and independent journalism. The Americans, above all, wanted to ensure that their journalistic standards would be adopted by the Germans. They tried to facilitate this in the post-war years through monitoring and direct guidance.117 In particular, the separation between news and opinion which had existed in opinion journalism in Germany since the 19th century and was driven to an extreme in the Third Reich, was supposed to be done away with.

The invention of the radio gave rise to a new type of journalist, the radio reporter who not only observed and took notes, but was also able to capture “sound bites” of people with the help of a recording device. The photograph shows Wolfgang Busalla (right), an employee of the Berliner Rundfunk, who interviewed a construction worker on the progress of the national reconstruction programme in February 1952. / Schack / Horst Sturm (b. 1923), central image Schack-Sturm 5.2.1952 “Rundfunkhaus Weberwiese”, black-and-white photograph, 5 February 1952; source: German Federal Archive

The development of journalism in the 20th century in Europe (as in other parts of the world) was further influenced by technological innovations. The discovery of electromagnetic waves led to the radio’s emergence as a mass medium that was introduced in all European countries in the 1920s. In most cases, radio broadcasting was either organised by or affiliated with the state. Only in the UK did the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) take on the character of a “public-service” company because of a royal charter. The organisational structure also had an effect on radio journalism: The medium itself was initially used mostly to educate and entertain. But informational programs also found their way into the line-up. The journalistic programming was initially still influenced by the model of the press and was only gradually supplemented by specific modes of presentation, reporting and interviews. Moreover, the possibility of direct transmission on the radio gave rise to the radio reporter as a journalistic type .

After the Second World War, another mass medium came into existence: television. Although its origins go back further, its spread was initially interrupted and delayed by the war. Thus television only began more or less simultaneously in European countries in the 1950s, though it was pervasive within a decade. In some countries, its organisation remained closely aligned to the state (e.g. in France), whereas in the Eastern Bloc it was (like radio) even entirely state-controlled. A number of Western European countries followed the model of the BBC and offered diverse forms of television as a “public service”, including the Scandinavian countries, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and Italy.

U.S. Newsreel ‘Hungarian Revolt’ 1956

“Hungarian Revolt”, US newsreel, Universal Studios, USA, 1956; source: US newsreel Universal Studios, 1956

Journalism now also entailed using moving images to convey information. This, in turn, required new formats to be developed or those of newsreels and the radio to be adapted, including live broadcasts, news programs, news magazines, documentaries, interviews, talk shows, etc. As the audio-visual medium involves highly complex production techniques, other professional roles were now required (cameraman, editor, etc.) along with the actual journalistic component. In “public-service” television, journalists were largely independent, despite corporate control, and free from the pressure of viewer ratings and audience preferences. Due to new transmission technologies (cable, satellite), this changed in the 1980s, when private-sector broadcasting was also authorized in Western Europe.

Jürgen Wilke, Mainz

Appendix

Literature

Adler, Hans Hermann: Anonymität, in: Walter Heide (ed.): Handbuch der Zeitungswissenschaft, Leipzig 1940, vol. 1, pp. 71–78.

Andrews, Alexander: The History of British Journalism from the Foundation of the Newspaper Press in England to the Repeal of the Stamp Act in 1855, New York, NY 1968, vol. 1–2.

Arndt, Johannes: Verkrachte Existenzen? Zeitungs- und Zeitschriftenmacher im Barockzeitalter zwischen Nischenexistenz und beruflicher Etablierung, in: Archiv für Kulturgeschichte 88 (2006), pp. 101–115.

Aspinall, Arthur: Politics and the Press 1780–1850, London 1973.

Barnhurst, Kevin G. / Nerone, John: Journalism History, in: Karin Wahl Jorgensen et al. (eds.): The Handbook of Journalism Studies, New York, NY et al. 2009, pp. 17-28.

Barnhurst, Kevin / Owens, James: Journalism, in: The International Encyclopedia of Communication 6 (2008), pp. 2557–2569.

Barrera, Carlos (ed.): Del Gacetero al Profesional del Periodismo: Evolución hístorica de los actors humanos del cuarto poder, Madrid 1999.

Barrera, Carlos / Vaz, Aires: The Spanish Case: A Recent Academic Tradition, in: Romy Fröhlich et al. (eds.): Journalism Education in Europe and North America: An International Comparison, Cresskill, NJ 2003, pp. 21–48.

Bauer, Oswald: Zeitungen vor der Zeitung: Die Fuggerzeitungen (1568–1605) und das frühneuzeitliche Nachrichtensystem, Berlin 2011 (Colloquia Augustana 28).

Baumert, Dieter Paul: Die Entstehung des deutschen Journalismus in sozialgeschichtlicher Betrachtung, Diss., Berlin et al. 1928.

Bellanger, Claude et al. (eds.): Histoire Générale de la Presse Française, Paris 1969, vol. 1: Des origines à 1814.

idem (eds.): Histoire Générale de la Presse Française, Paris 1969, vol. 2: De 1815 à 1871.

idem (eds.): Histoire Générale de la Presse Française, Paris 1972, vol. 3: De 1871 à 1914.

Bertaud, Jean Paul: Napoléon journaliste: Les bulletins de la gloire, in: Nouveau Monde éditions, online: http://www.cairn.info/article_p.php?ID_ARTICLE=TDM_004_0010 [02/08/2013].

Birkner, Thomas: Das Selbstgespräch der Zeit: Die Geschichte des Journalistenberufs in Deutschland 1605–1914, Cologne 2012.

Bjork, Ulf Jonas: “Scrupulous Integrity and Moderation”: The First International Organization for Journalists and the Promotion of Professional Behavior, 1894–1914, in: American Journalist 22,1 (2005), pp. 95–112.

Bösch, Frank: Die Zeitungsredaktion, in: Alexa Geisthövel et al. (eds.): Orte der Moderne: Erfahrungswelten des 19. und 20. Jahrhunderts, Frankfurt am Main et al. 2005, pp. 71–80.

Boyce, George et al. (eds.): Newspaper History: From the 17th Century to the Present Day, London et al. 1978.

Brandner-Radinger, Inge (ed.): Was kommt, was bleibt: 150 Jahre Presseclub Concordia, Vienna 2009.

Broersma, Marcel (ed.): Form and Style in Journalism: European Newspapers and the Representation of News 1880–2005, Leuven et al. 2007.

Brown, Lucy: Victorian News and Newspapers, Oxford 1985.

Brückmann, Ariane: Journalistische Berufsorganisationen in Deutschland: Von den Anfängen bis zur Gründung des Reichsverbands der Deutschen Presse, Cologne et al. 1997.

Brunöhler, Kurt: Die Redakteure der mittleren und größeren Zeitungen im heutigen Reichsgebiet von 1800–1848, Diss., Leipzig 1933.

Bundock, Clement J.: The National Union of Journalists: A Jubilee History 1907–1957, Oxford 1957.

Burke, Peter: Early Modern Venice as a Center of Information and Communication, in: John Martin et al. (eds.): Venice Reconsidered: The History and Civilization of an Italian City State, 1297–1797, Baltimore, MD et al. 2000, pp. 389–419.

Censer, Jack R.: The French Press in the Age of Enlightenment, London et al. 1994.

Chalaby, Jean K.: The Invention of Journalism, New York, NY 1998.

idem: Journalism as an Anglo-American Invention: A Comparison of the Development of French and Anglo-American Journalism, 1830–1920s, in: European Journal of Communication 11,3 (1996), pp. 303–326.

Chapman, Jane: Comparative Media History: An Introduction: 1789 to the Present, Cambridge 2005.

Charon, Jean-Marie: Journalist Training in France, in: Romy Fröhlich et al. (eds.): Journalism Education in Europe and North America: An International Comparison, Cresskill, NJ 2003, pp. 139–167.

Delporte, Christian: Les journalistes en France (1880–1950): Naissance et construction d’une profession, Paris 1999.

Dooley, Brendan et al. (eds.): The Politics of Information in Early Modern Europe, London 2001.

Engel, Matthew: Tickle the Public: One Hundred Years of the Popular Press, London 1996.

Eppel, Peter: “Concordia soll ihr Name sein…”: 125 Jahre Journalisten- und Schriftstellerverein: Eine Dokumentation zur Presse- und Zeitgeschichte Österreichs, Vienna et al. 1984.

Esser, Frank: Die Kräfte hinter den Schlagzeilen: Englischer und deutscher Journalismus im Vergleich, Freiburg et al. 1998.

idem: The “Training-on-the-Job” Tradition: Journalism Education at Media Organizations and / or Schools, in: Romy Fröhlich et al. (eds.): Journalism Education in Europe and North America: An International Comparison, Cresskill, NJ 2003, pp. 209–236.

Foerster, Cornelia: Sozialstruktur und Organisationsformen des Deutschen Preß- und Vaterlandsvereins von 1832/33, in: Wolfgang Schieder (eds.): Liberalismus in der Gesellschaft des deutschen Vormärz, Göttingen 1983, pp. 147–166.

Fuentes, Juan Francisco / Sebastián, Javier Fernández: Historia del Periodismo Español, Madrid 1997.

Gerhard, Ute et al. (eds.): “Dem Reich der Freiheit werb’ ich Bürgerinnen”: Die Frauen-Zeitung von Louise Otto, Frankfurt am Main 1979.

Gieseler, Jens / Kühnle-Xemaire, Elke: Der “Nordische Mercurius” – Eine besondere Zeitung des 17. Jahrhunderts? Eine sprachwissenschaftliche Untersuchung der Hamburger Zeitung, in: Publizistik 40 (1995), pp. 163–184.

Giffard, C. Anthony: The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: Precursor of the Press, in: Journalism History 9,1 (1982), pp. 11–15, 28.

Gómez Mompart, Josep L. et al. (eds.): Historia del Periodismo Universal, Madrid 1999.

Gopsill, Tom / Neale, Greg: Journalists: 100 Years of NUJ, London 2007.

Haferkorn, Hans Jürgen: Der freie Schriftsteller: Eine literatur-soziologische Studie über seine Entstehung und Lage in Deutschland zwischen 1750 und 1800, in: Archiv für Geschichte des Buchwesens 5 (1964), pp. 523–712.

Harris, Michael: Journalism as a Profession or Trade in the Eighteenth Century, in: Robin Myers et al. (eds.): Author / Publisher Relations during the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, Oxford 1983, pp. 37–62.

idem: London Newspapers in the Age of Walpole: A Study of the Origins of the Modern Press, Rutherford et al. 1987.

Høyer, Svennik: Newspapers without Journalists, in: Journalism Studies 4,4 (2003), pp. 451–463.

idem et al. (eds.): Diffusion of the News Paradigm 1850–2000, Göteborg 2005.

Humanes, María Luisa: Nacimiento de la Conciencia Profesional en los Periodistas Españoles (1883–1936), in: Carlos Barrera (ed.): Del Gacetero al Profesional del Periodismo, Madrid 1999, pp. 41–54.

Infelise, Mario: From Merchant’s Letters to Handwritten Political avvisi: Notes on the Origins of Public Information, in: Francisco Bethencourt et al. (eds.): Cultural Exchange in Early Modern Europe, Cambridge 2007, vol. 3, pp. 33–52.

idem: Prima dei giornali: Alle origini della pubblica informazione, Rome et al. 2002.

Jahn, Bruno (ed.): Die deutschsprachige Presse: Ein biographisch-bibliographisches Handbuch, München 2005, vol. 1–2.

Kinnebrock, Susanne: “Gerechtigkeit erhöht ein Volk?” Die erste deutsche Frauenbewegung, ihre Sprachrohre und die Stimmrechtsfrage, in: Jahrbuch für Kommunikationsgeschichte 1 (1999), pp. 135–172.

Koschwitz, Hansjürgen: Pressepolitik und Parteijournalismus in der UdSSR und der Volksrepublik China, Düsseldorf 1971.

Kutsch, Arnulf: Journalismus als Profession: Überlegungen zum Beginn des journalistischen Professionalisierungsprozesses in Deutschland am Anfang des 20. Jahrhunderts, in: Astrid Blome et al. (eds.): Presse und Geschichte: Leistungen und Perspektiven der historischen Presseforschung, Bremen 2008, pp. 289–325.

idem: Professionalisierung durch akademische Ausbildung: Zu Karl Büchers Konzeption für eine universitäre Journalistenausbildung, in: Tobias Eberwein et al. (eds.): Journalismus und Öffentlichkeit: Eine Profession und ihr gesellschaftlicher Auftrag: Festschrift für Horst Pöttker, Wiesbaden 2010, pp. 427–453.

Langenbucher, Wolfgang R. (ed.): Sensationen des Alltags: Meisterwerke des modernen Journalismus, München 1992.

Lauk, Epp: The Antithesis of the Anglo-American News Paradigm: News Practices in Soviet Journalism, in: Svennik Høyer et al. (eds.): Diffusion of the News Paradigm 1850–2000, Göteborg 2005, pp. 169–183.

Madland, Helga: Three Late Eighteenth-Century Women’s Journals: Their Role in Shaping Women’s Lives, in: Women in German Yearbook: Feminist Studies in German Literature and Culture 4 (1988), pp. 167–186.

Mancini, Paolo: Between Literary Roots and Partisanship: Journalism Education in Italy, in: Romy Fröhlich et al. (eds.): Journalism Education in Europe and North America: An International Comparison, Cresskill, NJ 2003, pp. 93–119.

Martens, Wolfgang: Die Geburt des Journalisten in der Aufklärung, in: Wolfenbütteler Studien zur Aufklärung, on behalf of the Lessing-Akademie ed. by Günter Schulz, Wolfenbüttel 1974, vol. 1, pp. 84–98.

Martin, Marc: Les grands reporters: Les débuts du journalisme moderne, Paris 2005.

idem: Structures de sociabilité dans la presse: Les associations de journalistes en France à la fin du XIXe siècle (1880–1910), in: Centre de recherches d’histoire de l’Université de Rouen dirigé par Françoise Thelamon: Sociabilité, pouvoirs et société: Actes du colloque de Rouen 24/26 Novembre 1983, Rouen 1987, pp. 497–509.

idem (ed.): Histoire et médias: Journalisme et journalistes françaises, Paris 1991.

Matthies, Marie: Journalisten in eigener Sache: Zur Geschichte des Reichsverbandes der deutschen Presse, Berlin 1969.

Moureau, François: Répertoire des nouvelles à la main: Dictionnaire de la presse manuscrite clandestine XVIe–XVIII siècle, Oxford 1999.

Müsse, Wilhelm: Die Reichspresseschule – Journalisten für die Diktatur? Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte des Journalismus im Dritten Reich, München 1995.

Murialdi, Paolo: La stampa italiana della liberazione alla crisi di fine secolo, Rome et al. 1995.

idem: Storia del giornalismo italiano, Bologna 1996.

Nevitt, Marcus: Women and the Pamphlet Culture of Revolutionary England 1640–1660, Aldershot 2006.

O’Boyle, Lenore: The Image of the Journalist in France, Germany and England, 1815–1848, in: Comparative Studies in Society and History 10 (1967–1968), pp. 290–302.

Palmer, Michael B.: Des petits journaux aux grandes agences: Naissance du journalisme moderne 1863–1944, Paris 1983.

idem: Parisian Newsrooms in the Late Nineteenth Century: How to Enter from the Agency Back Office, or Inventing News Journalism in France, in: Journalism Studies 4,4 (2003), pp. 479–487.

Popkin, Jeremy D.: Revolutionary News: The Press in France 1789–1799, Durham, NC 1990.

Prutz, Robert Eduard: Geschichte des deutschen Journalismus: Zum ersten Male vollständig aus den Quellen gearbeitet: Erster Theil, Hannover 1845, autotype Göttingen 1971.

Quintero, Alejandro Pizzaroso et al.: Historia de la Prensa, Madrid 1994.

Raymond, Joad: The Invention of the Newspaper: English Newsbooks 1641–1649, Oxford 1996.

idem (ed.): Making the News: An Anthology of the Newsbooks of Revolutionary England 1641–1660, New York, NY 1993.

idem (ed.): News Networks in Seventeenth-Century Britain and Europe, London et al. 2006.

idem: Pamphlets and Pamphleteering in Early Modern Britain, Cambridge 2003.

Requate, Jörg: Gescheiterte Existenzen: Zur Geschichte des Journalistenberufs im 19. Jahrhundert, in: Martin Welke et al. (eds.): 400 Jahre Zeitung: Die Entwicklung der Tagespresse im internationalen Kontext, Bremen 2008, pp. 335–354.

idem: Journalismus als Beruf: Entstehung und Entwicklung des Journalistenberufs im 19. Jahrhundert: Deutschland im internationalen Vergleich, Göttingen 1995.

Retallack, James: From Pariah to Professional? The Journalist in German Society and Politics, from the Enlightenment to the Rise of Hitler, in: German Studies Review 16 (1993), pp. 175–223.

Sánchez-Aranda, José J. / Barrera, Carlos: The Birth of Modern Newsrooms in the Spanish Press, in: Journalism Studies 4,4 (2003), pp. 489–500.

Scherer, Wilhelm: Geschichte der deutschen Literatur, 14th ed., Berlin 1920.

Schmolke, Michael: Philipp Hainhofer: Seine Korrespondenten und seine Berichte, in: Publizistik 7 (1962), pp. 224–349.

Sgard, Jean (ed.): Dictionnaire des Journalistes 1600–1789, Oxford 1999, vol. 1–2, online: http://dictionnaire-journalistes.gazettes18e.fr/ [02/08/2013].

Siebert, Frederick Seaton: Freedom of the Press in England 1476–1776: The Rise and Decline of Government Control, Urbana, IL 1965.

Smith, Anthony: The Newspaper: An International History, London 1979.

Sperlich, Monika: Journalist mit Mandat: Sozialdemokratische Reichstagsabgeordnete und ihre Arbeit in der Parteipresse: 1867 bis 1918, Düsseldorf 1983.

Stegers, Wolfgang: Der Leipziger Literatenverein von 1840: Die erste deutsche berufsständische Schriftstellerorganisation, in: Archiv für Geschichte des Buchwesens 19 (1978), pp. 225–364.

Stöber, Rudolf: Pressefreiheit und Verbandsinteresse: Die Rechtspolitik des “Reichsverbands der deutschen Presse” und des “Vereins Deutscher Zeitungs-Verleger” während der Weimarer Republik, Berlin 1992.

idem: Deutsche Pressegeschichte: Von den Anfängen bis zur Gegenwart, 2nd ed., Konstanz 2005.

Tusan, Michelle Elizabeth: Women Making the News: Gender and Journalism in Modern Britain, Urbana, IL et al. 2005.

Vivo, Filippo de: Information and Communication in Venice: Rethinking Early Modern Politics, Oxford et al. 2007.

Weaver, David H.: Journalism Education in the United States, in: Romy Fröhlich et al. (eds.): Journalism Education in Europe and North America: An International Comparison, Cresskill, NJ 2003, pp. 49–64.

Weber, Max: Politik als Beruf, in: Idem: Gesammelte Politische Schriften, ed. by Johannes Winckelmann, 2nd ed., Tübingen 1958, pp. 493–548.

Weckel, Ulrike: Zwischen Häuslichkeit und Öffentlichkeit: Die ersten deutschen Frauenzeitschriften im späten 18. Jahrhundert und ihr Publikum, Tübingen 1998.

Welke, Martin: Johann Carolus und der Beginn der periodischen Tagespresse: Versuch, einen Irrweg der Forschung zu korrigieren, in: Martin Welke et al. (eds.): 400 Jahre Zeitung: Die Entwicklung der Tagespresse im internationalen Kontext, Bremen 2008, pp. 9–116.

Welke, Martin et al. (eds.): 400 Jahre Zeitung: Die Entwicklung der Tagespresse im internationalen Kontext, Bremen 2008.

Wiener, Joel H. (ed.): Papers for the Millions: The New Journalism in Britain, 1850s to 1914, Westport, CT 1988.

Wijfjes, Huub: Kontrollierte Modernisierung: Form und Verantwortung im niederländischen Journalismus, in: Michael Prinz (ed.): Gesellschaftlicher Wandel im Jahrhundert der Politik, Nordwestdeutschland im internationalen Vergleich 1920–1960, Paderborn et al. 2007, pp. 175–195.

Wilke, Jürgen: Autobiographien als Mittel der Journalismusforschung: Quellenkritische und methodologische Überlegungen, in: Olaf Jandura et al. (eds.): Methoden der Journalismusforschung, Wiesbaden 2011, pp. 83–105.

idem: Im Dienste von Pressefreiheit und Rundfunkordnung. Zur Erinnerung an Kurt Häntzschel aus Anlaß seines hundertsten Geburtstages, in: Publizistik 34 (1989), pp. 7–28.

idem: Grundzüge der Medien- und Kommunikationsgeschichte, 2nd ed., Köln et al. 2008.

idem: The History and Culture of the Newsroom in Germany, in: Journalism Studies 4,4 (2003), pp. 465–477.

idem: Journalistenausbildung im Dritten Reich: Die Reichspresseschule, in: Beate Schneider et al. (eds.): Publizistik: Beiträge zur Medienentwicklung: Festschrift für Walter J. Schütz, Konstanz 1995, pp. 387–408.

idem: Korrespondenten und geschriebene Zeitungen, in: Johannes Arndt et al. (eds.): Das Mediensystem im Alten Reich der Frühen Neuzeit (1600–1750), Göttingen 2010, pp. 59–72.

idem: Media Genres, in: European History Online (EGO), published by the Institute of European History (IEG), Mainz 2010-12-03. URL: http://www.ieg-ego.eu/wilkej-2010-en URN: urn:nbn:de:0159-20100921478 [2013-08-02].

idem: Belated Modernization: Form and Style in German Journalism 1880–1980, in: Marcel Broersma (ed.): Form and Style in Journalism: European Newspapers and the Representation of News 1880–2005, Leuven et al. 2007, pp. 47–60.

idem: News Values in Transformation? About the Anglo American Influence of Post-war Journalism, in: APA – Austria Presse Agentur (ed.): The Various Faces of News (Agency) Journalism, Innsbruck 2002, pp. 65–72.

idem: Presseanweisungen im zwanzigsten Jahrhundert: Erster Weltkrieg – Drittes Reich – DDR, Cologne et al. 2007.

idem: Redaktionsorganisation in Deutschland: Anfänge, Ausdifferenzierung, Strukturwandel, in.: idem (ed.): Unter Druck gesetzt: Vier Kapitel deutscher Pressegeschichte, Cologne et al. 2002, pp. 9–67.

idem: Spion des Publikums, Sittenrichter und Advokat der Menschheit: Wilhelm Ludwig Wekhrlin (1739–1792) und die Entwicklung des Journalismus in Deutschland, in: Publizistik 38 (1993), pp. 322–334.

idem: Auf langem Weg zur Öffentlichkeit: Von der Parlamentsdebatte zur Mediendebatte, in: idem: Von der frühen Zeitung zur Medialisierung: Gesammelte Studien, Bremen 2011, vol. 2, pp. 61–76.

idem: Zeitungen und ihre Berichterstattung im langfristigen internationalen Vergleich, in: Deutsche Presseforschung Bremen (ed.): Presse und Geschichte, München 1987, vol. 2: Neue Beiträge zur historischen Kommunikationsforschung, pp. 287–305.

Wrede, Richard (ed.): Handbuch der Journalistik, 2. ed., Berlin 1906.

Würgler, Andreas: National and Transnational News Distribution 1400–1800, in: European History Online (EGO), published by the Leibniz Institute of European History (IEG), Mainz 2012-11-26. URL: http://www.ieg-ego.eu/wuerglera-2012-en URN: urn:nbn:de:0159-2012112605 [2013-08-02].

Notes

- Barnhurst / Nerone, Journalism History 2009, p. 19.

- See Harris, London Newspapers 1987, p. 99.

- Chalaby, Journalism 1996.

- See Martens, Geburt 1974, vol. 1, pp. 84–98.

- See Baumert, Entstehung 1928.

- See Birkner, Selbstgespräch 2012.

- See Delporte, Journalistes 1999.

- There seems to have been an exception at the beginning of the history of the research: Prutz, Geschichte 1971 [1845]. Although Prutz, coming from a history of literature perspective, also provided more of a history of the printed press than of journalism.

- See Andrews, History 1968, vol. 1–2; Aspinall, Politics 1973; Boyce, Newspaper History 1978.

- See Bellanger, Histoire Générale 1969, vol. 1–3.

- See Stöber, Deutsche Pressegeschichte 2005; Wilke, Grundzüge 2008.

- See Murialdi, La stampa italiana 1995; idem, Storia 1996.

- See Fuentes / Sebastián, Historia 1997; Barrera, Del Gacetero 1999.

- Smith, Newspaper 1979; Gómez Mompart, Historia 1999; Dooley, Politics 2001; Welke, 400 Jahre Zeitung 2008.

- Baumert, Die Entstehung 1928; Barnhurst / Nerone, Journalism History 2009.

- See Scherer, Geschichte 1920.

- See Giffard, Anglo-Saxon Chronicle 1982, pp. 11–15, 28.

- See Würgler, News Distribution 2012.

- See Bauer, Zeitungen 2011.

- See Burke, Early Modern Venice 2000; de Vivo, Information 2007.

- See Infelise, Prima dei giornali 2002; idem, From Merchant’s Letters 2007.

- “They were considered unreliable, even untrustworthy, and were tainted with odour of espionage”, transl. by C.R. (Bauer, Zeitungen 2011, p. 37).

- See Schmolke, Philipp Hainhofer 1962.

- Bellanger, Histoire Générale 1969, vol. 1; Moureau, Répertoire 1999.

- Dooley, Politics 2001.

- Baumert, Entstehung 1928.

- See Wilke, Korrespondenten 2010.

- See Welke, Johann Carolus 2008.

- Wilke, Media Genres 2010.

- See idem, Zeitungen 1987.

- See Siebert, Freedom 1965.

- See Wilke, Auf langem Weg 2011.

- See idem, Grundzüge 2008.

- See Raymond, Pamphlets 2003.

- See Harris, London Newspapers 1987, p. 105.

- See Aspinall, Politics 1973.

- See Sgard, Dictionnaire des Journalistes 1600–1789 1999, vol. 1–2.

- A work that is explicitly not only related to journalists is the two-volume “biographical-bibliographical” handbook edited by Bruno Jahn: Die deutschsprachige Presse (Jahn, Die deutschsprachige Presse 2005). Ranging from the 17th to the 20th century, this work presents about 6,000 short biographies and 207 detailed portraits of “handelnde Subjekte” (“acting subjects”) from the German-language press (p. 8). These were mainly extracted from the Deutsche Biographische Enzyklopädie and supplemented by 340 names. Besides journalists, editors and publishers, illustrators, cartoonists, photographers, print shop owners, etc. were also mentioned. “Zahlreiche Persönlichkeiten, die in anderen Zusammenhängen berühmt wurden”, it explains, “waren zumindest zeitweise journalistisch tätig.” (“Numerous individuals who became famous in other contexts were at least occasionally active as journalists”, transl. by C.R., p. 9)