Cancer in the ancient and medieval worlds was a poorly understood and highly feared disease.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Cancer, as a disease, is often thought of as a modern affliction, a consequence of industrialization, pollution, and contemporary lifestyle factors. However, historical and archaeological evidence shows that cancer has been present throughout human history. The understanding, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer in the ancient and medieval worlds reveal much about medical knowledge, cultural perceptions of disease, and the evolution of medical practices. This essay explores how cancer was perceived, documented, and treated from antiquity through the medieval period, drawing on sources from Egyptian, Greek, Roman, Islamic, and European medieval traditions.

Cancer in Antiquity

Egyptian Medicine and Early Evidence

Cancer, as a biological phenomenon, is often considered a modern disease due to its rising incidence in the industrial age; however, evidence suggests that cancer did exist in ancient civilizations, including Egypt. Ancient Egyptian physicians demonstrated an advanced understanding of a variety of ailments, and while the term “cancer” was not used in the modern sense, descriptions from ancient texts and physical remains offer insight into the disease’s historical presence. The Edwin Smith Papyrus, dated to the 17th century BCE, is one of the earliest known medical documents and includes a case study that may describe a form of breast cancer. The text outlines a “bulging tumor on the breast” and notes that “there is no treatment,” implying that the physicians recognized the terminal nature of certain abnormal growths, even if they lacked the terminology or pathology to diagnose cancer as we understand it today.1

Skeletal remains found at various archaeological sites in Egypt offer direct evidence for cancer in antiquity. A notable example is a skeleton discovered in a necropolis near Aswan, dating to approximately 4,000 BCE, which showed clear signs of metastatic carcinoma. Lesions on the bones, consistent with the spread of cancer from a primary site in the soft tissue, offer a compelling counterpoint to the assumption that cancer was exceedingly rare in premodern societies. Scholars have often debated the apparent scarcity of cancer diagnoses in ancient remains, suggesting that shorter life spans or taphonomic factors might obscure the true prevalence of the disease.2 Nevertheless, the presence of identifiable cancers in Egyptian mummies and skeletons proves that the disease is not exclusive to modernity and reinforces the notion that cancer is a fundamental aspect of the human condition.

Ancient Egyptian medicine was highly systematic, blending empirical observations with religious and magical thinking. While their treatments were based largely on herbal remedies and ritual incantations, Egyptian physicians demonstrated considerable anatomical knowledge, possibly owing to the practice of mummification. Despite this advanced understanding, there is no record of surgical excision or targeted treatment of tumors. The diagnostic framework of Egyptian medicine classified ailments into treatable, contestable, and untreatable conditions. Tumorous growths, when noted in surviving papyri, typically fell into the latter category. This suggests a resigned recognition of the limits of their medical practice in the face of such diseases.3 Furthermore, since cancer tends to affect older adults, and ancient Egyptian life expectancy was roughly 30–40 years, many cancers may have gone unnoticed or undocumented due to mortality from other causes.

Religious and cultural attitudes also shaped how Egyptians perceived and recorded disease. Illness was often interpreted as a manifestation of divine will or the result of spiritual imbalance. As such, ailments that disfigured the body or appeared without obvious cause may have been attributed to supernatural forces rather than natural pathology. This cultural lens likely influenced the limited discussion of tumors in medical texts and may explain why cancer receives less attention compared to trauma, infections, and parasitic diseases. Moreover, the social roles of scribes and priests in the medical system may have further constrained the dissemination of medical knowledge to what was deemed cosmologically significant.4 Nevertheless, the material record, including detailed embalming practices and autopsies of mummies using modern technology, increasingly provides a clearer picture of the disease burden in ancient Egypt.

Recent advancements in paleopathology and radiological analysis have revolutionized the study of disease in antiquity. Computed tomography (CT) scanning and molecular diagnostics applied to mummified remains have uncovered hidden pathologies, including cancers of the bone, breast, and soft tissue. A 2015 study using CT imaging on a well-preserved mummy from the Ptolemaic period revealed clear evidence of nasopharyngeal cancer. These findings underscore the value of interdisciplinary research bridging archaeology, medicine, and biology to reassess long-standing assumptions about the epidemiology of ancient diseases. As more non-invasive technologies become available, researchers expect to uncover further instances of cancer in mummified remains, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of its presence and perception in ancient Egypt.5 The study of cancer in this context not only illuminates ancient health but also highlights the timelessness of the disease and the continuity of human suffering across millennia.

Greek Medical Thought: Hippocrates and Galen

In ancient Greece, the conceptualization of cancer began to move beyond the mystical and into the realm of rational inquiry. The very term “cancer” originates from the Greek word karkinos, meaning “crab,” which was used by Hippocrates to describe tumors with radiating projections resembling a crab’s legs. Hippocratic physicians observed that some tumors were immovable and painful, with thick surrounding veins that reminded them of crab limbs, leading to the metaphorical name.6 This development marked a significant shift from the Egyptian approach by emphasizing natural rather than supernatural causes. The Hippocratic Corpus, a collection of medical texts attributed to Hippocrates and his school, contains several references to hard swellings, particularly in the breast, which they often deemed untreatable. Rather than invoking divine punishment or magic, the Greeks explained disease through imbalances in bodily humors—blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile—with cancer specifically linked to an excess of black bile.

The theory of the four humors, systematized by Hippocrates and later expanded by Galen, became central to Greek medical understanding. According to this model, black bile accumulated in certain parts of the body, especially in women’s breasts, and hardened into cancerous masses. Women were thought to be more prone to such accumulations due to their inherently colder and wetter constitutions, which supposedly facilitated stagnation.7 Treatments recommended in the Hippocratic tradition included dietary restrictions, bloodletting, and purgatives to reestablish humoral balance, though surgical intervention was often avoided, particularly for internal tumors. These therapies reflect the Greek reluctance to engage in invasive surgery unless the condition appeared superficial and non-terminal. The conservative therapeutic approach to cancer underscored their recognition of the limits of ancient medical science, and their respect for nature’s course in terminal illnesses.

Galen of Pergamon, one of the most influential Greek physicians of the Roman era, inherited the Hippocratic model but expanded the anatomical and physiological framework of cancer. Galen further codified the association between black bile and cancer, believing that it originated from the spleen and could localize in vulnerable tissues. He distinguished between benign and malignant tumors, noting that some could remain harmless while others were “hard, fixed, and painful,” progressing to fatal stages.8 Galen’s descriptions of cancer in the uterus, breasts, and face were detailed and clinically astute for their time. Although Galen did occasionally advocate surgical removal of tumors, particularly when they were clearly circumscribed and accessible, he cautioned against operating on advanced cases, noting the risk of rapid deterioration or death. His writings profoundly influenced both Byzantine and Islamic medicine and shaped European oncological theory well into the Renaissance.

Social and philosophical attitudes in ancient Greece also shaped perceptions of cancer. Greek physicians, especially in the Hippocratic school, sought to separate medical practice from religious superstition, yet the public often viewed chronic illnesses with fatalistic resignation. Because cancer often presented as an incurable condition with visible and painful symptoms, it was surrounded by social stigma and fear. Women, being more frequently afflicted with breast and uterine cancers, were particularly vulnerable to exclusion or pity, with some literary texts referring obliquely to their suffering without naming the disease explicitly. While medical texts offered empirical observations, Greek tragedy and philosophy reflected a broader existential view of illness, aligning incurable disease with human frailty and the inescapability of fate.9 The stoic and Epicurean schools in particular used disease as a metaphor for internal corruption, contributing to moral as well as medical interpretations of cancer.

Modern paleopathological evidence supports the idea that cancer, while less common than today, was not unknown in ancient Greece. Skeletal remains from sites such as Demetrias and the Athenian Kerameikos have revealed lesions indicative of metastatic bone cancers. Advances in radiographic imaging and DNA analysis have allowed researchers to identify patterns of disease in remains previously thought to show only trauma or infection. For instance, a 2021 study reexamining Hellenistic-era burials found osteolytic lesions and tumor-induced remodeling consistent with cancers that likely originated in soft tissues.10 These findings, though relatively rare, challenge long-standing assumptions that cancer was absent or negligible in ancient times. Instead, they affirm what Greek physicians themselves acknowledged—cancer was known, feared, poorly understood, and largely untreatable. The Greek legacy lies not in curing cancer, but in naming it, describing it, and attempting to understand it through reason and observation rather than myth.

Galen of Pergamon (129–c. 216 CE), the most influential physician of antiquity, elaborated on humoral theory and cancer pathology.5 Galen described cancer as a type of “knot” or “hard swelling” and reiterated its connection to black bile. He was skeptical of surgical excision for internal cancers but advocated for removal of some external tumors, albeit with limited success. Galen’s writings profoundly influenced medical thought well into the medieval period.

Cancer in the Roman World

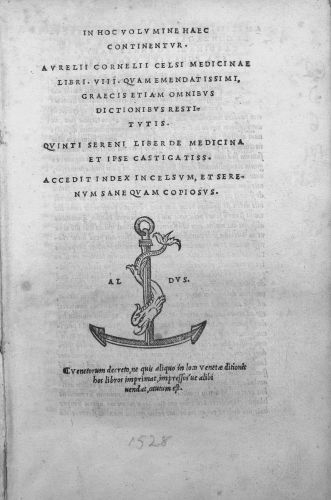

Roman medicine, while heavily indebted to its Greek predecessors, made important contributions to the understanding and treatment of cancer, even if these remained limited by the period’s medical knowledge. Roman physicians inherited the humoral theory from Hippocrates and Galen, with black bile again identified as the primary culprit in cancer’s etiology. Celsus, a prominent Roman encyclopedist of the first century CE, described cancer in his medical treatise De Medicina, noting that it was named for the crab-like shape of its vessels and was usually incurable. He wrote that early-stage cancers could potentially be removed with surgery, but once the malignancy had spread, any intervention would only hasten death.11 This pragmatic attitude reflected a general Roman tendency to categorize illnesses according to their treatability, a tradition going back to the Greek triage of diseases as treatable, contestable, or untreatable.

Galen, who practiced in the Roman Empire during the 2nd century CE, continued to refine the cancer concept and deepened its classification within humoral theory. He differentiated between carcinos (benign tumor) and carcinoma (malignant tumor), associating the latter more closely with systemic effects and pain. His case studies included breast, uterine, and facial cancers, and he emphasized their slow progression and poor prognosis. Galen’s medical writings became authoritative across the Roman Empire and later throughout medieval Europe and the Islamic world. Although he did sometimes recommend surgical removal for tumors that were well-localized and accessible, he remained cautious, especially for deeply embedded or ulcerated growths. His emphasis on the humoral cause of cancer discouraged aggressive surgical approaches, instead promoting balancing treatments such as purging, diet, and phlebotomy.12 These conservative interventions reflect both a philosophical and physiological understanding of disease rooted in equilibrium and natural limits.

Despite the theoretical foundation, Roman medicine was also highly practical and localized, especially among military physicians and urban practitioners. In Roman military hospitals (valetudinaria), surgeons encountered a range of pathologies, including tumors, although these institutions focused more on trauma and acute illnesses. Surgical instruments discovered at Pompeii and other Roman sites suggest that tumor excision was technically possible and may have been attempted in selected cases. Soranus of Ephesus, a Roman-era physician writing in Greek, described breast cancer in his Gynecology and advised against surgery unless the tumor was small and movable.13 In many cases, treatments reverted to herbal poultices, cauterization, and spiritual remedies, especially among the lower classes who lacked access to elite physicians. This duality—between rational medical theory and empirical, often folk-based practice—underscores the complexities of Roman healthcare and the challenges in managing chronic, mysterious diseases like cancer.

Cancer was also intertwined with Roman cultural and social norms, particularly in the realm of women’s health. Female patients with breast or uterine tumors were often subject to moral and social judgments. Romans viewed bodily decay with particular revulsion, and women with visible deformities could be socially marginalized. Moreover, Roman ideals of beauty and fertility shaped how illnesses were perceived and addressed. Medical texts often depict female patients as emotionally unstable and biologically porous, making them especially vulnerable to diseases caused by imbalance or retention of bodily fluids, such as breast milk or menstrual blood. These gendered medical views helped perpetuate the idea that women were especially susceptible to cancer.14 Although such ideas were grounded in faulty physiological assumptions, they shaped Roman therapeutic responses and societal attitudes toward female cancer patients.

Archaeological and paleopathological findings from Roman sites increasingly support textual evidence of cancer in antiquity. Studies of skeletal remains from Roman Britain and North Africa have revealed bone lesions consistent with metastatic cancer, often in the spine, pelvis, or skull. A 2016 study using CT scanning on a Roman-era mummy from Egypt revealed signs of rectal cancer, marking one of the earliest confirmed cases of soft-tissue malignancy in the Roman world.15 These discoveries suggest that cancer was more prevalent than the written sources imply and underscore the limitations of textual transmission in capturing the full epidemiological landscape. While Roman physicians may have lacked the tools to fully understand cancer, their observations laid a foundation for centuries of oncological thought. More importantly, their record shows that they faced the same kinds of suffering, uncertainty, and therapeutic impotence that persist in aspects of cancer care today.

The Medieval World

Cancer in the Islamic Golden Age

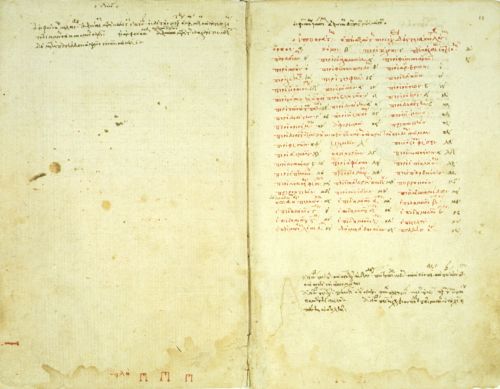

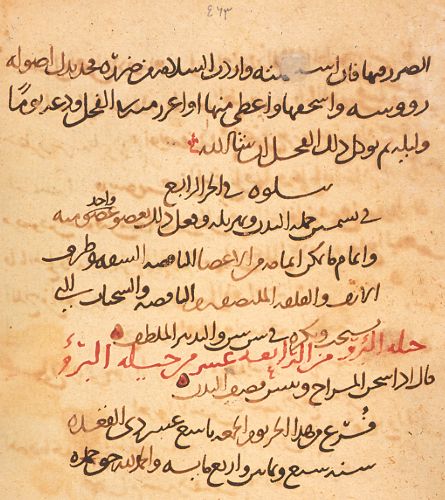

During the Islamic Golden Age (8th–13th centuries CE), scholars built upon the classical medical knowledge of Greece and Rome, including the study of cancer, while advancing it through rigorous clinical observation and integration with their own philosophical and religious contexts. Islamic physicians such as Al-Razi (Rhazes) and Ibn Sina (Avicenna) were well-versed in the writings of Hippocrates and Galen, which were translated into Arabic through major efforts by scholars like Hunayn ibn Ishaq. Cancer continued to be understood primarily through the humoral framework, with black bile identified as the etiological agent responsible for hard, persistent tumors.16 However, Muslim physicians did not merely reproduce Greco-Roman thought; they refined and expanded upon it through more detailed categorization of cancers, improvements in diagnostics, and nuanced approaches to treatment. Al-Razi, in his Kitab al-Hawi (Comprehensive Book), emphasized careful observation and recognized the difference between superficial and deep-seated tumors, advising caution in surgical intervention based on the tumor’s stage and the patient’s constitution.17

The most influential and systematized treatment of cancer in the Islamic world was presented by Ibn Sina in his monumental work Al-Qanun fi al-Tibb (The Canon of Medicine). In this medical encyclopedia, which remained authoritative in both the Islamic world and Latin Europe for centuries, Ibn Sina classified cancer under “swellings” (awram) and distinguished between those that were non-ulcerative and ulcerative. He described the characteristics of cancerous masses—firm, immovable, painful, and dark-colored—and echoed Galen in attributing their cause to the concentration of black bile. Yet Ibn Sina innovated by stressing the importance of early intervention, advising surgical removal only when the tumor was still localized and had not ulcerated. He emphasized complete excision and cauterization to prevent recurrence, warning that partial removal could exacerbate the condition.18 This understanding shows a sophisticated awareness of cancer’s invasive nature, even within the constraints of pre-modern pathology.

In addition to surgical and humoral treatments, Islamic physicians explored pharmacological and dietary approaches to managing cancer. Ibn al-Nafis and other physicians recommended concoctions of purgatives, emetics, and compound herbal remedies designed to evacuate black bile and rebalance the humors. Diet played a central role in maintaining health and preventing disease recurrence; foods believed to encourage the production of black bile—such as old cheese, dried meats, and sour fruits—were restricted.19 Medicinal substances such as myrrh, lead-based compounds, and caustic alkalis were applied topically to ulcerated tumors in an attempt to arrest their spread. These treatments, though empirical in nature, reflected a deeply holistic worldview, in which cancer was not only a physical condition but also an imbalance of the soul and spirit. Physicians frequently consulted astrological charts and spiritual texts, suggesting an intersection of science, religion, and cosmology in the medieval Islamic approach to cancer.

The hospital (bimaristan) system, which flourished under Islamic rule in cities like Baghdad, Damascus, and Cairo, provided structured settings for cancer care. These institutions combined patient treatment with medical education and research, and some had specialized wards for chronic diseases. Surgical tools recovered from Islamic archaeological contexts suggest that excision and cauterization were practiced with considerable precision. Al-Zahrawi (Albucasis), the great Andalusian surgeon, included in his Kitab al-Tasrif detailed illustrations of surgical instruments and procedures for removing tumors. He cautioned that only skilled surgeons should undertake cancer operations, stressing that the knife must cut beyond the visible tumor to remove its roots, lest it return more virulent.20 This recognition of cancer recurrence and metastasis, although not described in modern terms, shows an early grasp of its aggressive behavior. The Islamic emphasis on clinical skill, hygiene, and documentation helped preserve and transmit oncological knowledge across centuries and regions.

Despite these advances, medieval Islamic physicians recognized the limitations of their methods. Terminal cancers, especially of the internal organs, were often treated palliatively, with an emphasis on relieving pain and spiritual preparation for death. While Islamic medicine generally rejected the idea of divine punishment as the cause of disease—unlike many medieval Christian interpretations—it still viewed health and illness within a theological framework. Patients and doctors alike understood suffering as a trial, and healing as ultimately dependent on the will of God. The preservation and advancement of medical knowledge, including the understanding of cancer, was seen as both a scientific and religious duty. This integration of reason, observation, and faith created a rich and nuanced medical culture, one that preserved ancient oncological theories while advancing them toward early clinical sophistication.21

Cancer in Medieval Europe

In medieval Europe, understandings of cancer were deeply shaped by inherited classical ideas, particularly those of Galen and Hippocrates, transmitted through both Latin and Arabic sources. The dominant explanatory model remained the humoral theory, in which an excess of black bile was believed to cause hard, immovable tumors. Cancer was viewed not as a distinct disease but as a form of pathological swelling (tumor), and it was categorized along with other growths under the broader category of apostemata. These concepts were codified in texts like the Articella, a popular medieval medical compendium derived from Galenic teachings and Arab-Islamic commentaries. Physicians learned that cancers were most common in the female breast and reproductive organs, though they could also occur in the face, throat, and extremities.22 Due to the perceived incurability of most cancers, particularly when ulcerated, many medieval European medical texts recommended palliative care rather than surgical intervention, a stance that would remain prevalent until the early modern period.

Medieval surgical texts, particularly those influenced by Arabic works such as those of Al-Zahrawi, did describe procedures for excising tumors, though these were rarely undertaken due to the high risks involved. Guy de Chauliac, a prominent 14th-century French surgeon, in his Chirurgia Magna, advised against surgical intervention for cancers unless the tumors were small, localized, and not ulcerated. He described breast cancer in detail, noting the hardness and discoloration of the tissue, and emphasized the need for complete excision followed by cauterization to prevent regrowth.23 However, he also cautioned that even successful removal often led to recurrence and worsening of the condition. Most physicians and surgeons instead recommended topical ointments, purgatives, and dietary changes intended to expel or reduce the production of black bile. The reliance on humoral treatments, despite limited success, reflects the epistemological constraints of the period, in which anatomy was rarely studied through dissection and disease was understood in systemic rather than localized terms.

Gender played a significant role in the medieval European discourse on cancer. Female bodies, widely considered more porous and humoral-imbalanced than male bodies, were thought to be particularly vulnerable to diseases caused by retained fluids, such as breast cancer. This vulnerability was tied to views about menstruation, lactation, and fertility. The Trotula, a widely read medieval compendium on women’s medicine attributed to the school of Salerno, associated breast cancer with the obstruction of menstrual blood or milk.24 Treatments for women often combined internal and external remedies, including purgatives to cleanse the womb, emollients to soften tumors, and religious rituals. The boundaries between medical, magical, and spiritual approaches were permeable, particularly for female patients. As Barbara Duden and Monica Green have shown, these gendered medical narratives reinforced broader cultural ideas about women’s bodies as naturally defective and in need of constant regulation.25

Spiritual explanations and religious treatments for cancer were pervasive in medieval Europe. Disease in general, and cancer in particular, was frequently interpreted as divine punishment or a trial sent by God. Saints’ relics, pilgrimage, and prayer were integral to the healing process. The cult of Saint Peregrine, who was believed to have been miraculously cured of a cancerous leg tumor, gained popularity during the later Middle Ages, especially among those suffering from incurable illnesses.26 Healing shrines such as those at Canterbury, Lourdes, and Santiago de Compostela saw throngs of cancer sufferers seeking divine intervention. Clerical authorities often endorsed these practices, while some monastic infirmaries provided a combination of prayer, care, and rudimentary medicine. These religious interpretations did not preclude medical treatment but coexisted with it, forming a pluralistic system of healing in which physicians, clergy, and patients navigated overlapping frameworks of causality and care.

Despite the limitations of medieval European medicine, the period saw increasing institutionalization of healthcare that would later support advances in medical science. Hospitals founded by religious orders in towns and cities often provided palliative care for cancer sufferers, especially those who were poor or marginalized. University-based medicine, which emerged in places like Salerno, Bologna, Paris, and Oxford, began to formalize medical education and standardize texts such as Galen’s works and Avicenna’s Canon. Although anatomical knowledge remained constrained by religious prohibitions on dissection, autopsy was occasionally practiced in special cases, allowing limited internal observation of disease. By the end of the medieval period, a small but growing body of empirical observations was challenging traditional models, laying the groundwork for later shifts in medical thinking during the Renaissance and Scientific Revolution.27 Cancer remained a mysterious and feared condition, but its treatment and conceptualization were slowly evolving within the broader currents of medieval intellectual and institutional development.

Cancer in the Early Modern Era

The early modern era marked a turning point in the understanding and study of cancer, though many medieval theories persisted well into the 18th century. The humoral theory, inherited from Galen and Hippocrates, continued to dominate medical explanations. Cancer was still associated with an excess of black bile, a melancholic humor believed to coagulate in specific parts of the body—most notably the female breast. However, Renaissance humanism, with its emphasis on classical revival and empirical observation, began to challenge this traditional framework. Anatomists such as Andreas Vesalius initiated a revolution in bodily understanding through dissection, revealing more precise internal anatomy. Though Vesalius himself did not focus extensively on cancer, his rejection of Galenic anatomical authority opened the door for later physicians to question other long-held assumptions, including the humoral origin of cancer.28 This period also saw the gradual separation of surgery from general medicine, allowing surgeons to develop a more practical approach to tumor removal.

As anatomical studies flourished, physicians and surgeons began to produce more detailed case studies of cancerous growths. Ambroise Paré, a French royal surgeon in the 16th century, described numerous instances of breast cancer and advised surgical intervention only with extreme caution due to the risk of recurrence and patient mortality.29 He offered graphic descriptions of tumors, noting their hardness, discoloration, and tendency to ulcerate, and he experimented with various treatments including excision, cauterization, and the application of caustic substances. Paré’s writings reflect a growing awareness that cancer was both locally destructive and systematically dangerous. Yet despite these observations, the understanding of cancer’s mechanism remained vague and speculative. The debate over whether cancer was primarily a local or systemic disease would persist for centuries, with most early modern practitioners concluding that even if surgically removed, the cancerous “humor” could linger or migrate elsewhere in the body.

The 17th century saw further refinements in medical theory as Paracelsianism and iatrochemistry challenged Galenic medicine. Paracelsus and his followers introduced new chemical approaches to disease, seeing illnesses—including cancer—as resulting from chemical imbalances rather than humoral misalignments. Cancer, in this view, was sometimes interpreted as a product of mineral or salt imbalances, or as an internal fermentation process.30 While these ideas were often speculative, they encouraged experimentation with chemical remedies, including mercury and arsenic-based compounds. This trend merged with growing interest in pathology and microscopy. In 1665, Robert Hooke’s Micrographia introduced the term “cell,” laying the groundwork for cellular pathology, though cancer would not be understood at the cellular level until the 19th century. Early modern physicians still lacked a comprehensive model for carcinogenesis, but their shift toward empirical observation, dissection, and experimentation marked a gradual departure from medieval mysticism.

Cancer also took on new symbolic and social meanings in the early modern period. The disease was increasingly associated with femininity, sexuality, and morality. Breast cancer, in particular, was often viewed as the product of sinful living, excessive sexuality, or emotional trauma, particularly in women past childbearing age. This moralizing narrative reflected broader cultural anxieties about female bodies, aging, and bodily decay.31 Treatments could include not only surgical excision but also bleeding, purging, and strict dietary regimens designed to “cool” the body and restore balance. Religious interpretations did not disappear—many still saw cancer as divine punishment—but they were increasingly supplemented or replaced by naturalistic explanations. Still, the psychological and social burden of cancer remained immense, and medical texts often conveyed a sense of helplessness and inevitability in the face of the disease’s progression.

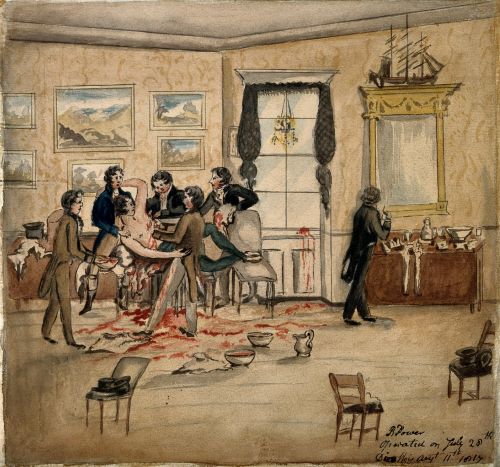

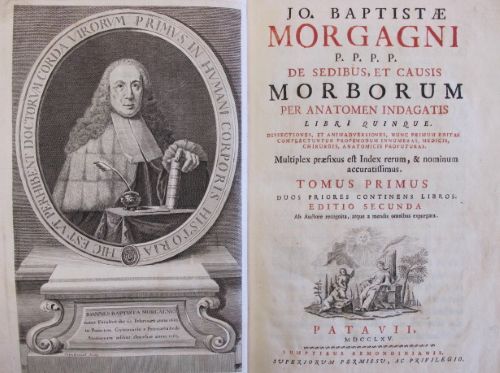

By the 18th century, European medicine began shifting toward pathological anatomy, with cancer becoming a central subject of post-mortem investigation. Physicians such as Giovanni Battista Morgagni correlated clinical symptoms with autopsy findings, helping to classify tumors by location and type. Morgagni’s work, De Sedibus et Causis Morborum per Anatomen Indagatis (1761), examined over 700 cases, many of which involved cancerous lesions in organs like the stomach, uterus, and liver.32 His meticulous case studies helped disentangle cancer from the purely humoral model and demonstrated its devastating effects on internal organs. Meanwhile, public cancer surgeries became spectacles in hospitals like St. Bartholomew’s in London or the Hôtel-Dieu in Paris. These operations, conducted without anesthesia, were acts of both bravery and desperation, and their limited success underscored the urgent need for better understanding and treatment. Though the true biological nature of cancer remained elusive, the early modern era laid essential groundwork for the medical advances of the 19th century and beyond.

Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries

The 19th century witnessed profound changes in the understanding and treatment of cancer, driven by the rise of pathological anatomy and cellular theory. Building on the anatomical investigations of Giovanni Battista Morgagni and others, Rudolf Virchow’s publication of Cellular Pathology in 1858 fundamentally transformed medical thinking. Virchow posited that all diseases, including cancer, arose from abnormalities in cells rather than from humoral imbalances or organ-level dysfunctions.33 He described cancer as uncontrolled cellular proliferation and identified malignancy through cell division and structural disorganization. This theory provided a mechanistic and observable foundation for understanding cancer and laid the groundwork for modern oncology. Microscopy became essential to diagnosis, and cancer was increasingly classified according to histological characteristics. This period also saw the development of histopathology as a medical specialty, further refining cancer classification and prognosis.

Surgical advances in the 19th century paralleled these theoretical developments. The introduction of anesthesia in the 1840s and antiseptic practices by the 1860s revolutionized cancer surgery. Surgeons could now attempt more extensive and invasive procedures with reduced risk of infection and patient trauma. Radical mastectomy, pioneered by William Halsted in the 1880s, became the standard treatment for breast cancer. Halsted’s approach involved the removal of the breast, underlying chest muscles, and lymph nodes in an attempt to prevent metastasis, based on the belief that cancer spread centrifugally from a primary tumor.34 Though successful in some cases, the procedure was disfiguring and often performed without full understanding of cancer’s systemic nature. Meanwhile, cancer hospitals and research centers began to emerge, such as the Royal Marsden in London and Memorial Hospital in New York, formalizing oncology as a distinct area of clinical and scientific inquiry.

In the early 20th century, new technologies and discoveries further reshaped cancer diagnosis and treatment. Wilhelm Röntgen’s discovery of X-rays in 1895 enabled physicians to visualize tumors inside the body, and radiation therapy soon followed. Marie and Pierre Curie’s isolation of radium spurred the development of brachytherapy and external beam radiation, both of which became standard treatments for various cancers.35 The idea of using radioactive substances to destroy cancerous tissue gained wide acceptance, though early experimentation often exposed patients and physicians to harmful levels of radiation. Chemotherapy emerged more gradually, with the first significant breakthroughs coming during and after World War II. Observations of the cell-killing properties of nitrogen mustard led to the development of cytotoxic drugs like methotrexate and 5-fluorouracil.36 These therapies marked a turning point, offering treatment options for systemic cancers previously considered untreatable, though side effects and drug resistance remained serious challenges.

Alongside technological advances, the 20th century saw the rise of cancer as a public health concern and subject of activism. In the early 1900s, cancer was still largely stigmatized and discussed in hushed tones. However, by the mid-century, national campaigns—such as those by the American Cancer Society—began to promote education, screening, and research funding. Pap smears, mammography, and colonoscopy helped facilitate early detection, improving survival rates for certain cancers.37 Simultaneously, the epidemiological study of cancer led to the identification of major risk factors, such as tobacco use, asbestos exposure, and viral infections like HPV. Richard Doll and Austin Bradford Hill’s landmark studies in the 1950s linked smoking to lung cancer, transforming both medical understanding and public policy.38 These developments positioned cancer not merely as a medical condition but as a social and political issue demanding systemic responses.

By the late 20th century, cancer research had entered the molecular era. The discovery of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes, such as RAS, p53, and BRCA1, revolutionized the biological understanding of cancer as a genetic disease. Scientists began to decode the molecular pathways responsible for cell growth, apoptosis, and metastasis, leading to the concept of personalized or precision medicine. Targeted therapies such as imatinib (Gleevec), approved in 2001 for chronic myeloid leukemia, exemplified this shift by attacking specific molecular abnormalities in cancer cells.39 Meanwhile, advances in immunotherapy—including checkpoint inhibitors and CAR-T cell therapies—offered new hope for treating cancers previously considered intractable. The complexity of cancer biology became more apparent, yet so did the prospects for more effective, individualized treatments. Thus, the 19th and 20th centuries together formed a bridge from early surgical interventions and rudimentary theories to the sophisticated, multi-modal approach of contemporary oncology.

Conclusion

Cancer in the ancient and medieval worlds was a poorly understood but feared disease. Across cultures, from Egyptian scribes to Islamic physicians and medieval European healers, cancer was described primarily by its visible manifestations and linked to humoral imbalances or spiritual causes. Treatments were limited by medical knowledge and technological constraints, and surgery, when attempted, was fraught with risk.

The persistence of cancer through history underscores its biological roots and the ongoing human struggle to understand and combat this complex disease. The evolution of cancer knowledge from antiquity through the medieval period laid the groundwork for modern oncology, blending empirical observation with cultural and religious interpretation.

Appendix

Endnotes

- James P. Allen, The Art of Medicine in Ancient Egypt (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005), 42–45.

- Michaela Binder et al., “On the Antiquity of Cancer: Evidence for Metastatic Carcinoma in a Young Man from Ancient Nubia (c. 1200 BC),” PLoS ONE 9, no. 3 (2014): e90924.

- Rosalie David, The Ancient Egyptians: Beliefs and Practices (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2002), 119–124.

- John F. Nunn, Ancient Egyptian Medicine (London: British Museum Press, 1996), 85–89.

- Salima Ikram and Aidan Dodson, The Mummy in Ancient Egypt: Equipping the Dead for Eternity (London: Thames & Hudson, 1998), 157–159.

- Vivian Nutton, Ancient Medicine (London: Routledge, 2004), 119–121.

- Owsei Temkin, Galenism: Rise and Decline of a Medical Philosophy (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1973), 83–85.

- Galen, On the Affected Parts, trans. Rudolph E. Siegel (Basel: S. Karger, 1976), 135–138.

- Helen King, The Disease of Virgins: Green Sickness, Chlorosis and the Problems of Puberty (London: Routledge, 2004), 27–30.

- King, The Disease of Virgins.

- Celsus, De Medicina, trans. W. G. Spencer (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1935), 7.25.

- Galen, On Tumors Against Nature, in Galen: Selected Works, trans. P. N. Singer (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 176–180.

- Soranus, Gynecology, trans. Owsei Temkin (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991), 108–110.

- Rebecca Flemming, Medicine and the Making of Roman Women: Gender, Nature, and Authority from Celsus to Galen (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 56–61.

- Salima Ikram and Aidan Dodson, The Mummy in Ancient Egypt.

- Peter E. Pormann and Emilie Savage-Smith, Medieval Islamic Medicine (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), 120–122.

- Al-Razi, Kitab al-Hawi (The Comprehensive Book), trans. and ed. Farid Haddad (Beirut: Dar al-Kotob al-Ilmiyah, 1990), 3:276–280.

- Avicenna (Ibn Sina), The Canon of Medicine, trans. Laleh Bakhtiar (Chicago: Kazi Publications, 2007), 721–725.

- Nasser S. Al-Dabbagh, “On Cancer in Medieval Islamic Medicine,” History of Medical Sciences Journal 14, no. 3 (2019): 211–215.

- Al-Zahrawi, Kitab al-Tasrif, trans. M. S. Spink and G. L. Lewis (London: The Wellcome Institute, 1973), 308–312.

- Peter Adamson, Philosophy in the Islamic World (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), 232–235.

- Nancy G. Siraisi, Medieval & Early Renaissance Medicine: An Introduction to Knowledge and Practice (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997), 43–45.

- Guy de Chauliac, Inventarium sive Chirurgia Magna, trans. E. Nicaise (Paris: Asselin & Houzeau, 1890), 302–306.

- Monica H. Green, The Trotula: An English Translation of the Medieval Compendium of Women’s Medicine (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002), 111–113.

- Barbara Duden, The Woman Beneath the Skin: A Doctor’s Patients in Eighteenth-Century Germany, trans. Thomas Dunlap (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991), 12–15; Monica H. Green, “Women’s Medical Practice and Health Care in Medieval Europe,” Signs 14, no. 2 (1989): 434–447.

- Caroline Walker Bynum, Holy Feast and Holy Fast: The Religious Significance of Food to Medieval Women (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987), 193–196.

- Luke Demaitre, Medieval Medicine: The Art of Healing, from Head to Toe (Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger, 2013), 97–102.

- Andrew Cunningham, The Anatomical Renaissance: The Resurrection of the Anatomical Projects of the Ancients (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1997), 114–117.

- Ambroise Paré, The Collected Works of Ambroise Paré, trans. Thomas Johnson (New York: Milford House, 1968), 485–490.

- Allen G. Debus, The Chemical Philosophy: Paracelsian Science and Medicine in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (New York: Science History Publications, 1977), 225–230.

- Susan P. Mattern, The Slow Moon Climbs: The Science, History, and Meaning of Menopause (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019), 129–134.

- Giovanni Battista Morgagni, De Sedibus et Causis Morborum per Anatomen Indagatis, trans. Benjamin Alexander (London: A. Millar, 1769), vol. 1, 178–183.

- Rudolf Virchow, Cellular Pathology: As Based Upon Physiological and Pathological Histology, trans. Frank Chance (London: J.B. Lippincott, 1860), 25–29.

- Barron H. Lerner, The Breast Cancer Wars: Hope, Fear, and the Pursuit of a Cure in Twentieth-Century America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 43–48.

- Lerner, The Breast Cancer Wars.

- Vincent T. DeVita Jr., Theodore S. Lawrence, and Steven A. Rosenberg, Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology, 10th ed. (Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer, 2015), 17–22.

- Elizabeth Toon, “Cancer as the General Population Knows It: 20th-Century American Social History,” in Cancer in the Twentieth Century, ed. David Cantor (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008), 327–331.

- Richard Doll and A. Bradford Hill, “Smoking and Carcinoma of the Lung: Preliminary Report,” British Medical Journal 2, no. 4632 (1950): 739–748.

- Siddhartha Mukherjee, The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer (New York: Scribner, 2010), 402–412.

Bibliography

- Adamson, Peter. Philosophy in the Islamic World. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Al-Dabbagh, Nasser S. “On Cancer in Medieval Islamic Medicine.” History of Medical Sciences Journal 14, no. 3 (2019): 211–215.

- Al-Razi. Kitab al-Hawi (The Comprehensive Book). Translated and edited by Farid Haddad. Beirut: Dar al-Kotob al-Ilmiyah, 1990.

- Al-Zahrawi. Kitab al-Tasrif. Translated by M. S. Spink and G. L. Lewis. London: The Wellcome Institute, 1973.

- Allen, James P. The Art of Medicine in Ancient Egypt. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005.

- Avicenna (Ibn Sina). The Canon of Medicine. Translated by Laleh Bakhtiar. Chicago: Kazi Publications, 2007.

- Binder, Michaela, Neal Spencer, Charlotte Roberts, Daniel Antoine, and Ahmed S. M. el-Halem. “On the Antiquity of Cancer: Evidence for Metastatic Carcinoma in a Young Man from Ancient Nubia (c. 1200 BC).” PLoS ONE 9, no. 3 (2014): e90924.

- Bynum, Caroline Walker. Holy Feast and Holy Fast: The Religious Significance of Food to Medieval Women. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987.

- Celsus. De Medicina. Translated by W. G. Spencer. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1935.

- Chauliac, Guy de. Inventarium sive Chirurgia Magna. Translated by E. Nicaise. Paris: Asselin & Houzeau, 1890.

- Cunningham, Andrew. The Anatomical Renaissance: The Resurrection of the Anatomical Projects of the Ancients. Aldershot: Ashgate, 1997.

- David, Rosalie. The Ancient Egyptians: Beliefs and Practices. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2002.

- Demaitre, Luke. Medieval Medicine: The Art of Healing, from Head to Toe. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger, 2013.

- Debus, Allen G. The Chemical Philosophy: Paracelsian Science and Medicine in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. New York: Science History Publications, 1977.

- DeVita, Vincent T. Jr., Theodore S. Lawrence, and Steven A. Rosenberg. Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer, 2015.

- Doll, Richard, and A. Bradford Hill. “Smoking and Carcinoma of the Lung: Preliminary Report.” British Medical Journal 2, no. 4632 (1950): 739–748.

- Duden, Barbara. The Woman Beneath the Skin: A Doctor’s Patients in Eighteenth-Century Germany. Translated by Thomas Dunlap. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991.

- Flemming, Rebecca. Medicine and the Making of Roman Women: Gender, Nature, and Authority from Celsus to Galen. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Galen. On the Affected Parts. Translated by Rudolph E. Siegel. Basel: S. Karger, 1976.

- Galen. On Tumors Against Nature. In Galen: Selected Works, translated by P. N. Singer, 165–185. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

- Green, Monica H. The Trotula: An English Translation of the Medieval Compendium of Women’s Medicine. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002.

- Green, Monica H. “Women’s Medical Practice and Health Care in Medieval Europe.” Signs 14, no. 2 (1989): 434–447.

- Ikram, Salima, and Aidan Dodson. The Mummy in Ancient Egypt: Equipping the Dead for Eternity. London: Thames & Hudson, 1998.

- King, Helen. The Disease of Virgins: Green Sickness, Chlorosis and the Problems of Puberty. London: Routledge, 2004.

- Lerner, Barron H. The Breast Cancer Wars: Hope, Fear, and the Pursuit of a Cure in Twentieth-Century America. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Mattern, Susan P. The Slow Moon Climbs: The Science, History, and Meaning of Menopause. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019.

- Morgagni, Giovanni Battista. De Sedibus et Causis Morborum per Anatomen Indagatis. Translated by Benjamin Alexander. London: A. Millar, 1769.

- Mukherjee, Siddhartha. The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer. New York: Scribner, 2010.

- Nunn, John F. Ancient Egyptian Medicine. London: British Museum Press, 1996.

- Nutton, Vivian. Ancient Medicine. London: Routledge, 2004.

- Paré, Ambroise. The Collected Works of Ambroise Paré. Translated by Thomas Johnson. New York: Milford House, 1968.

- Pormann, Peter E., and Emilie Savage-Smith. Medieval Islamic Medicine. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007.

- Siraisi, Nancy G. Medieval & Early Renaissance Medicine: An Introduction to Knowledge and Practice. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997.

- Soranus. Gynecology. Translated by Owsei Temkin. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991.

- Temkin, Owsei. Galenism: Rise and Decline of a Medical Philosophy. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1973.

- Toon, Elizabeth. “Cancer as the General Population Knows It: 20th-Century American Social History.” In Cancer in the Twentieth Century, edited by David Cantor, 327–355. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008. Virchow, Rudolf. Cellular Pathology: As Based Upon Physiological and Pathological Histology. Translated by Frank Chance. London: J.B. Lippincott, 1860.

Originally published by Brewminate, 05.20.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.