Most every home had at least one hearth.

Introduction

Fire was a versatile and important part of medieval life. It was used to provide light, heat homes, and cook food. Medieval Europe could be very cold. Many homes had poor or nonexistent insulation, not to mention open windows with little more than simple shutters or curtains to block out winter weather. Even rich people who could afford glass in their windows suffered from drafty rooms.

Most every home had at least one hearth, and more well-to-do people could have one in each major room. However, heating from hearths is inconsistent; it can be uncomfortably warm right next to the hearth fire, while only a short distance away you are at the mercy of icy drafts. Though it was certainly better than nothing, these fires were hardly the luxurious central heating developed nations enjoy today.

The fire was generally allowed to die down to embers during the night, due to concerns about unwatched materials catching flame. In the winter, this meant that medieval homes became very cold. No wonder many people shared beds! Other households (with larger budgets) had beds surrounded by thick, heavy curtains.

Lighting Your Home, Medieval Style

Homes were generally very dark. During the day, natural light was the only source of illumination. The interiors of medieval homes were typically so dark that visitors entering from outside would need a moment to adjust their eyes to the lower light. At night, fire was the only artificial source of light. The hearth provided a low level of light, while candles were used for more specific light sources.

Candles were precious resources. Many candles were made out of an animal fat called “tallow”. Cleaner-burning beeswax was more expensive, and was restricted to the most affluent homes. The poorest people used “rushlights”, in which the dried inner pith of rushes were dipped in tallow and set alight. Rushlights were easy to make, but provided little light compared to more expensive candles.

The use of fire was risky in part because of building materials in use at the time. The richest members of society – kings, queens, lords – might have their homes built using stone, but materials such as wood and mud were more common.

Roofs were often thatched with reeds and other dried plant matter (though, given how tightly thatch is packed, it burns much more slowly than you might expect).

Even affluent people spread rushes and straw on their floors to insulate their homes and provide a cushioning layer.

Poorer people, such as peasants, occasionally housed their farm animals with them during the winter. Feed could provide fuel for a dropped candle or errant spark. Accumulated animal dung, gathered in a pile, could potentially produce enough heat through decomposition to start fires.

In the city, wooden buildings were placed closely together. There were no formal fire codes, and construction was minimally regulated. If a fire started in one home, it could easily spread to its neighbors. Periodically, large and devastating fires swept through major European cities, such as London and Hamburg, Germany.

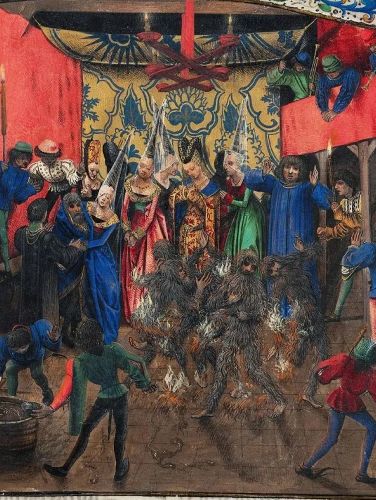

The Bal des Ardents

Fire could strike anyone, at any time. One incident, called the Bal des Ardents, nearly killed King Charles VI of France. In January 1393, the King and a small group of companions entered a masquerade ball costumed as “wild men”. The ball was held to celebrate the third marriage of one of the Queen’s ladies in waiting; the remarriage of a widow was frequently seen as an occasion for tomfoolery, a French folk practice known as charivari. The appearance of costumed people at these events was an occasional feature.

The mens’ costumes consisted of flax embedded in resin, both highly flammable materials. Orders were given that the majority of torches were to be extinguished, and no one carrying a torch would be allowed to enter the hall. However, this rule was broken when Charles’ brother entered the hall with torches and approached too closely to the dancers. Their costumes caught fire almost immediately, and four men died as a result.

The King survived only because he stood apart from his compatriots, and was shielded by his young aunt, who threw her voluminous skirts over the King to protect him from flying sparks. Another reveler survived by diving into a large wine vat.

The incident caused great upset amongst French citizens, who already saw the court as extravagant and plagued by troubles. Neither did it do much to uphold the image of the King, who was in often delicate health and unable to rule.

Fire as a Weapon and as Punishment

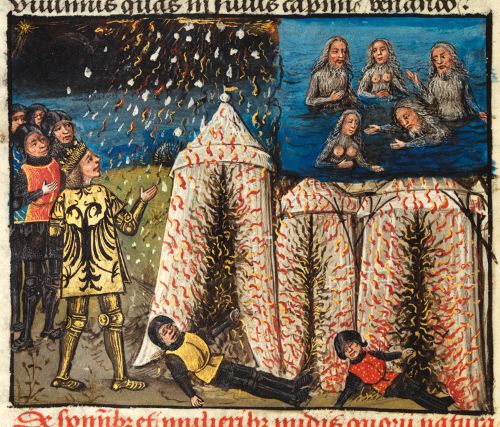

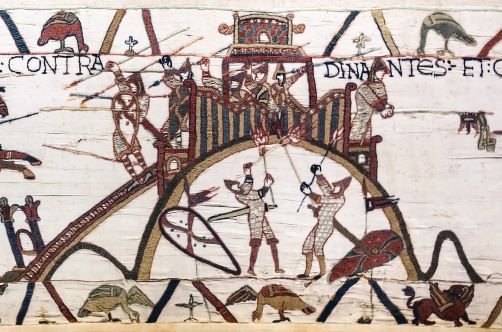

Fire was also used during warfare. Weapons could range from relatively simple to complex. In 1063, William I of England besieged Mayenne, in northwestern France. Archers shot fire into the garrison, while two young boys made it into the castle and started a fire within the walls. Stone castles were actually fairly susceptible to fire. Though stone and brick are relatively fire resistant, castles were filled with flammable materials. Carpets, wall hangings, and floor coverings could easily catch on fire. Especially intense heat could even damage the stone, given enough time and a high temperature.

More advanced incendiary devices could be launched by catapults and trebuchets. From the 12th century, Muslim warriors in Syria were using grenade-style weapons made out of clay or glass. Greek fire was used by Byzantine warriors in the early Middle Ages.

Death by fire was also an occasional and horrific punishment during the Middle Ages, often for people accused of witchcraft or heresy. Perhaps the most famous medieval person to die by burning at the stake was Joan of Arc, a young French woman who became a religious and military figure during the Hundred Years’ War.

Originally published by the Denver Firefighters Museum Blog, 11.14.2014, to the public domain.