Exploring what made Parisiens laugh in a moment of crisis through the prism of a vaudeville play.

By Dr. Vlad Solomon

Historian and Independent Scholar

This article, Laughter in the Time of Cholera, was originally published in The Public Domain Review under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0. If you wish to reuse it please see: https://publicdomainreview.org/legal/

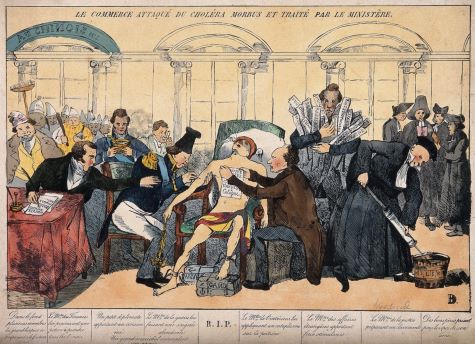

The year 1832 in France still conjures up images of rebellion and barricades thanks to the enduring pathos of Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables. For the real-life Parisians, however, who inspired the novel’s iconic characters, it was not only a year of lost causes, bloody street battles, and political disillusionment. It was also, in the parlance of our times, a “pandemic year” during which thousands — more than 18,000 in Paris; 100,000 across France1 — succumbed to a wave of cholera that had been causing havoc throughout Asia, Russia, and parts of East Central Europe since the 1820s. Although germ theory was still in its infancy at the time, people were quick to grasp the contagious nature of the disease and sought to speedily bury their dead as authorities scrambled desperately to meet the demands of an unprecedented public health crisis. A recent transplant to Paris, the German poet Heinrich Heine noted in a letter penned in mid-April 1832 — less than a month after the first recorded case of cholera in the French capital — the “disagreeable” sight of “great furniture wagons used for ‘moving’ now moving about as dead men’s omnibuses . . . going from house to house for fares and carrying them by dozens to the field of rest.”2

Parisians had been vaguely aware of the advancing wave of choléra-morbus, as the disease was then known, since at least 1830, when papers began regularly reporting on outbreaks in the Russian Empire’s eastern provinces.3 By early 1831, news of the ravages caused by the pandemic in Poland and East Prussia was already circulating by word of mouth in the capital. Legitimists (ultra-conservative supporters of the exiled Bourbon dynasty) imagined rootless political radicals spreading the disease with the same ease that they proselytised the “dangerous classes”, while the Church foresaw in the potential upheaval an “opportunity to renew its ties with a population that had shown itself unfaithful to the Catholic religion and the Bourbon dynasty”.4 Medical authorities, meanwhile, were certain that “the topographical situation of France is so advantageous that there is little to fear in this country from choléra-morbus or any other pestilential epidemic”.5

It is less certain what ordinary Parisians made of the alarming news, but those with money and time to spend on leisure turned to popular entertainment for comfort and comic relief. The early 1830s saw a spectacular resurgence of satire in France — the sort that could be both brilliant and crass, as the drawings of Honoré Daumier attest — but what is usually forgotten is that not all satire was printed for an exclusively reading public. Much was meant for the stage, particularly in 1831 when the July Monarchy’s promises of free speech did not yet ring entirely hollow.6 Only the previous year, French theatre had experienced one of the most tumultuous episodes in its venerable history with the so-called Battle of Hernani, a skirmish — at times quite physical — between the Romantic rebels congregated around Victor Hugo and the classicist fogeys who saw in Romanticism only the glorification of deformity and vulgarity.7 That was, however, the “serious” theatre of the Comédie Française which, generally speaking, only the educated bourgeoisie and aristocracy had any real interest in, as Hugo himself was forced to concede.8 A petit-bourgeois office clerk or shop assistant with no particular interest in the rarefied culture wars of the day — the sort that Balzac, and later Flaubert, caricatured without mercy — was much more likely to go for a one-act farce at one of Paris’ several vaudeville theatres.

Since the days of the French Revolution, vaudeville, a form of light theatre with roots in medieval minstrelsy, had both reflected and challenged the social and political upheavals of the day in ways that government figures usually found objectionable. In 1807, Napoleon reduced the number of Parisian theatres to just eight and while the regimes that followed the fall of the Empire proved slightly less persecutory at first, they too eventually introduced strict censorship laws.9 As a result of this stifling atmosphere, vaudeville writers (known as vaudevillistes) only ever managed to skirt the political arena for most of the nineteenth century and rarely came close to embodying an actual political consciousness. One unintended effect of this self-censorship was that vaudeville gradually increased both the scope and sharpness of its critique by refocusing its sights on society at large. If the folly of kings, emperors, prelates, and ministers could only be hinted at with a mischievous wink, the state of France itself (and Paris in particular) provided virtually unlimited fodder for the theatrical imagination.

As theatre historians have recently argued, the secret to vaudeville writers’ enduring success throughout the nineteenth century — a success that extended well beyond France10 — rested not on their literary talents, which were rarely substantial, but on their skill in employing “finely sketched . . . satirical portraits” to depict “the social and political idiosyncrasies” of their times.11 It was this skill in particular that enabled them to play a leading role in the “modern spectacular culture” that began taking shape in the Paris of the 1830s and 40s.12 Vaudevillistes were, mutatis mutandis, the sitcom screenwriters of their age, serving up the sort of light yet topical satire that simultaneously lampooned and affirmed the “performative dimensions” of social interaction, status seeking, and personal identity.13 Think Fawlty Towers punctuated by brief musical interludes.

Hundreds of vaudevilles inundated the stages of popular Parisian theatres throughout 1831, but one play stands out with its inventive use of emerging social panics as a springboard for an absurd yet trenchant critique of politics and culture. Entitled Les pilules dramatiques, ou le choléra-morbus (The dramatic pills, or the cholera), the play followed the time-honoured musical revue format in which a few humorous scenes are tied together by short comical songs. Its surreal and cleverly “meta” plot centres on personified versions of Paris’ most emblematic theatres as they check themselves into the sanatorium of a certain Dr Scarlatin, “médecin des théâtres” (theatre doctor), convinced they have contracted the cholera.14 Their condition, it gradually becomes apparent, is not the result of any infection or indeed curable by any doctor’s pilules since it derives solely from ressentiment and insecurity. The vaudeville theatres feel overshadowed by exclusive establishments like the Paris Opera and want to “rise above” their present condition while the more respectable theatres fear the end of censorship and the increased competition it promised to bring about. Adding to the confusion of the plot, some theatres are represented, purely for comedic effect, by abstract concepts like Illusion or by exaggerated versions of controversial historical characters such as Jacques Dupont, a brutal officer of the early Bourbon Restoration who still embodied the worst excesses of monarchical reaction.15

A dubious bourgeois named simply Bourgeois, who is introduced as a capitaliste looking to exchange “the Stock Market backstage for that of the theatre world”, attempts to sell life insurance to Dr Scarlatin, but only ends up giving unsolicited advice to the theatres, urging them to stick to the tried and tested “honest comedy” of former times.16 Spectators would have detected, in this ostensibly innocent piece of advice, an ironic commentary on the process of embourgeoisement that vaudeville had been undergoing for some years thanks to the incredibly prolific and successful dramatist Eugène Scribe (1791–1861). Scribe, whom Hugo despised as the epitome of crass commercialism and whose reputation rapidly waned following his death in 1861, had almost single-handedly managed to revolutionise vaudeville in the 1820s by shearing it of its atavistic carnivalesque excesses and forcing it into a corset of respectability — something which typically amounted to simple plots and minimal minstrelsy. Despite his shady past and insipid comments, Bourgeois is the only character who manages to make any sense, illustrating the ease with which vaudeville writers could simultaneously satirise and flatter their largely middle- and lower-middle-class audiences.

Doctor Scarlatin, whose name is tellingly reminiscent of a disease — scarlatine, French for scarlet fever — is naturally more than willing to offer his would-be patients medicine. The 1830s marked the dawn of a great age of réclame (advertisement) in France and spurious ads for all sorts of miracle drugs and vitality-restoring contraptions were becoming increasingly frequent in the popular press. “To cure all of your illusions, take my pills”, Scarlatin announces , but their effect is not the intended one.17

Having taken the miracle cure, the theatres go predictably “mad” and descend into an ever more cacophonous airing of grievances. They are momentarily brought to order by Monsieur Jovial, a well-known vaudeville character of the day,18 who assumes the title of Attorney General and stages a mock trial for “these dangerous theatres”. Declaring himself a “good doctrinaire” — a mocking reference to the Restoration-era moderate royalists who found themselves in power under the July Monarchy — Jovial sentences the offenders to “keep quiet when it comes to kings . . . bourgeois . . . lovers . . . mothers . . . and the deceased” and to “refrain from ridiculing the multitude”.19 While censorship was relatively lax by Restoration-era standards, the genuinely free press enshrined in the Charter of 1830 — the July Monarchy’s founding document — remained stubbornly elusive. Periodicals were still subject to security deposits and stamp duty and publishers (along with authors, editors, and vendors) could still face prosecution for writings or drawings deemed overtly libellous of the king and his government.20

The play’s stand-out scenes are undoubtedly the final two, during which the world itself abruptly comes to an end, pointing to the banalisation of an intense political disillusionment that was no longer the preserve of embittered republicans. Having just announced, “with pleasure”, that the world is about to be turned to ashes thanks to a comet set on a collision course with Earth, Dr Scarlatin joins the other characters in a jaunty danse macabre. More than an amusing plot twist, the comet too reflected the stuff of everyday life. Biela’s Comet, first spotted in the 1770s and named after the German astronomer Wilhelm von Biela, who had demonstrated its periodicity in 1826, was widely rumoured at the time to return within a “worrying” distance of Earth in 1832.21 Some even openly prayed that it would finally make a clean sweep of all “earthly tyrants”.22

“The human race, starting tomorrow, will wake up in bed, quite dead!” the characters all sing, awaiting their own destruction while Monsieur Jovial excitedly proclaims “Oh! The machine is creaking!” In a time of cholera, the only remedy that can cure political anger (colère) and the social malaise of ressentiment — bringing peace to a society saturated with interminable conspiracies, rivalries, betrayals, and vendettas — is, it turns out, complete annihilation. Courtesans, bankers, rentiers, misers, and “old Crassuses” must all contend with the realization that all of their “cash will be turned to trash”.23

The show, however, always means to go on and, in a moment of proto-Dadaist absurdity, the comet itself is transformed into a character. This parodic version of the Final Judgement would likely not have passed muster with the censors earlier in the century (or after 1835, when censorship laws became much more stringent). The personified Comet — a flamboyant stand-in for all feared and imagined apocalypses, including the encroaching cholera — informs the other characters that no reprieve will be possible; everyone and everything must go and, in any case, “the end of the world is a rather curious spectacle that one can hardly be annoyed at having to witness at least once in life”.24 Not wishing to appear callous, however, the Comet demands its victims to elaborate on what anyone “down here” could possibly have to regret and, with this cue, the other characters break into one final song. Its lyrics neatly sum up the sources of national decadence as they would have been recognised by a theatre-going public of the 1830s:

The press has everywhere thrown off its quest for truth [a jeté ses lumières]

And by its torches the whole world is bedazzled

Your fathers were all subject to abject ignorance

But you are all undone by an excess of knowledge

All can be understood, all can be said, all is explained:

All peoples, proud of having won their laws through struggle,

Have used up every option, from monarchy to the republic,

And rack their brains defining all their rights . . .

You’ve seen your great men of the people

Fight battles in the cause of freedom

Only to then go begging for a sinecure [quêter des ministères]

Like vagrants who search endlessly for alms.

Your literature amounts to nothing now

Having picked up all of romanticism’s errors,

Its writings all reveal the face of Nature,

Poor and decrepit, surrounded by great horrors.

And if it’s love and its enchanted powers

You now seek with regret to call to mind,

Trembling with fear before your politicians,

All love, alas! has flown away into the yonder.

Deists have finally found refuge in your midst,

And now, as if to prove their power and his own,

God, whom the Saint-Simonians25 would see dethroned,

Destroys the world and owes you nothing more.

The Comet then turns to the audience and defiantly invites spectators to boo should they find the piece deserving of nothing else, “since the world is drawing to an end [anyway].” In fact, audiences loved it — “it is full of wit, honest malice . . . bitter criticism . . . and verve”, the critics announced26 — and it is easy to see why. Shady capitalists (a term which already carried strong connotations of unscrupulous speculation), out-of-touch thespians, self-seeking politicians, shameless quacks, decadent art, godless cabals, and a press consumed with selling copy while pretending to enlighten — all are lampooned with unusual frankness to the toe-tapping music of popular tunes.

If vaudeville’s preoccupation with imitation, competition, forgery, hypocrisy, and status consciousness appears slightly more politically charged than the brooding nostalgia of Romanticism, the navel-gazing of realism, or the austere moralizing of naturalism, it is, of course, not because vaudeville writers were any more perceptive or foresighted than their romantic, realist, or naturalist contemporaries. It is because vaudeville remained immanently focused on the “bourgeois” reality that more sophisticated and imaginative authors sought merely to excoriate, escape, or earnestly moralise on. As Alexandre Dumas fils noted in the preface to one of his vaudevillesque comedies, “We [playwrights] have nothing to invent, we have only to see, to feel and to restore, in a special form, that which all spectators must immediately recall having heard or seen without becoming aware of it until [they see it on stage].”27

Vaudeville writers who lacked Eugène Scribe’s commercial genius and influence were typically paid a pittance for their efforts and often worked in teams in order to maximise productivity and secure the patronage of theatre directors by having them appear as co-authors. It is no surprise then that the author of Les pilules dramatiques, identified only as “M. le docteur Mesenthère” (Doctor Mesentery) on the title page, was in fact four authors: Michel Masson, Claude-Louis-Marie de Rochefort, Ferdinand de Villeneuve, and Adolphe de Leuven. They were all veteran vaudevillistes well-versed in the difficult art of pandering to popular taste. While it is tempting to see in their one-act farce merely an amusing distraction for a nerve-racked public, beyond the surreal silliness and slapstick, the play’s vaguely “anti-system” message contained the inchoate essence of a pessimistic outlook that would mature later in the nineteenth century.

Although the relatively relaxed cultural atmosphere brought about by the July Monarchy did not survive for long, versions of the politically-charged motifs in Les pilules dramatiques found a home in many nineteenth-century vaudevilles, even in times when censors were able to indulge their zeal (such as during the authoritarian Second Empire). More importantly, these same tried-and-tested motifs provided a key ingredient in a new kind of political journalism that emerged in France in the mid-to-late-nineteenth century; a brash, violently worded, decadence-obsessed opinion journalism epitomised in the 1880s by the writings of populist pamphleteers like Édouard Drumont and Henri Rochefort. The former was a failed vaudevilliste28 who turned to a lifetime of colère against imagined Jewish cabals, while the latter was none other than Claude-Louis-Marie de Rochefort’s son and a successful vaudevilliste in his own right who used his theatrical reputation to launch a successful journalistic career in the mid-1860s.29

Despite reports of “nine hundred dead each day” being common in mid-1832, many Parisian theatres remained open as the cholera pandemic raged and even after the death (also from cholera) of Prime Minister Casimir Perier plunged the capital into political chaos.30 By early June the general disenchantment, which the authors of Les pilules dramatiques had made a literal song and dance about the previous year, exploded into a republican insurrection quickly and brutally suppressed by government troops and later immortalised in Les Misérables. “Few vaudevillistes”, noted Le Figaro a couple of weeks after the abortive revolt, “can escape the contagion of playing the opposition at the moment . . . such is the importance that is placed on a rhyme or a bit of wordplay [in the belief that they] can topple governments”.31

Appendix

Endnotes

- François Delaporte, Disease and Civilization: The Cholera in Paris, 1832, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1986), 77; B.M., “Aperçu de nos connaissances sur le vibrion cholérique, la toxine cholérique et la vaccination anticholérique”, Biologie medicale: Revue mensuelle des sciences biologiques 6.9 (November 1908): 352.

- Heinrich Heine, “French Affairs: Letters from Paris”, in The Works of Heinrich Heine, vol. 7, trans. Charles Godfrey Leland (London: William Heinemann, 1893), 183.

- Le Temps, March 11, 1830; Le Constitutionnel, October 15, 1830.

- Delaporte, 60.

- Dominique-Jean Larrey, Mémoire sur le choléra-morbus (Paris: J.–B. Baillière, 1831), 27.

- On visual satire and censorship during the July Monarchy, see Patricia Mainardi, “Of Pears and Kings”, The Public Domain Review (January 9, 2020).

- Already a successful author by 1830, the twenty-seven-year-old Hugo defied all theatrical conventions with his play in which a young outlaw known as Hernani battles various swashbuckling intrigants in sixteenth-century Spain to win the hand of Doña Sol in marriage. Hernani’s attempts ultimately fail and the play concludes with a melodramatic triple suicide. The “battle” took place on the play’s opening night (February 28) at the Comédie Française, and was sparked more by the visceral animosity that existed between the long-haired bohemians who supported Hugo and the defenders of “good taste” than by any rarefied aesthetical arguments.

- Federico Tarragoni, “Le théâtre de 1830: Faire un peuple par le spectacle ou moraliser le parterre populaire?” Tumultes 42 (2014): 147–64.

- See Robert J. Goldstein, “Censorship of Caricature and the Theater in Nineteenth-Century France: An Overview”, in Les censures dans le monde: xixe–xxie siècle, ed. Laurent Martin (Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2016), 31–46.

- The theatre-going public in the Scandinavian countries proved particularly receptive to Parisian humour. For examples of advertisements announcing performances of translated French vaudevilles see Folkets Avis (Copenhagen), March 18, 1863; Folkets Tidning (Lund), March 18, 1864.

- Jean-Claude Yon and Olivier Bara, “Introduction”, in Eugène Scribe: Un maître de la scène théâtrale et lyrique au XIXe siècle, eds. Jean-Claude Yon and Olivier Bara (Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2016), Kindle.

- Jennifer Terni, “A Genre for Early Mass Culture: French Vaudeville and the City, 1830-1848”, Theatre Journal 58.2 (2006): 226.

- Terni, 226.

- Le Docteur Mesenthère (Claude-Louis-Marie de Rochefort, Ferdinand de Villeneuve, Adolphe de Leuven, Michel Masson), Les pilules dramatiques, ou le choléra-morbus: revue critique et politique en un acte (Paris: R. Riga, 1831). Certain doctors did in fact specialise in tending to theatre troupes and were known as médecins des théâtres. Many had of course no qualms about profiting from thespian vanity and routinely prescribed their patients various questionable “elixirs” (Le Constitutionnel, January 7, 1838).

- J. Lucas-Dubreton, “Trestaillons et compagnie”, Revue des deux mondes (October 1955).

- Mesenthère, Les pilules dramatiques, 6.

- Mesenthère, 12.

- Emmanuel Théaulon and Adolphe Choquart, Monsieur Jovial, ou, l’huissier-chansonnier (Paris: Unknown, 1827).

- Mesenthère, Les pilules dramatiques, 23.

- Raimund Rütten, “L’opposition républicaine et la censure”, in La Caricature Entre République et Censure: L’imagerie Satirique En France de 1830 à 1880: Un Discours de Résistance?, eds. Philippe Régnier, Raimund Rütten, Ruth Jung, and Gerhard Schneider (Lyon: Presses universitaires de Lyon, 2019), 80–86.

- La France nouvelle, February 13, 1831; June 1, 1830.

- Prosper Baumès, “Épitre à la comète de 1832” (Epistle to the comet of 1832), Journal du commerce de la ville de Lyon et du département du Rhône (February 9, 1831). Far from being an eccentric crank, Baumès was a surgeon at the Hôpital de l’Antiquaille in Lyon and the author of Précis théorique et pratique sur les maladies vénériennes (1840) and other medical treaties. The “comet panic” of 1832 also likely inspired Edgar Allan Poe to write one of his bleakest short stories, “The Conversation of Eiros and Charmion” (1839) in which the world is destroyed by a comet.

- Mesenthère, Les pilules dramatiques, 24–25.

- Mesenthère, 26.

- Followers of the reformer and philosopher Claude-Henri de Rouvroy, Count de Saint-Simon (1760–1825), the Saint-Simonians were far from a cohesive movement but generally professed a blend of humanitarianism, utopian socialism, and eclectic spirituality. They believed that anciens régimes across Europe and elsewhere would be succeeded by societies under the care of industrial and scientific experts and sought to replace conventional religion with a “new Christianity” centred on charismatic leadership, pantheism and free love. In 1832, a Saint-Simonian sect led by Barthélemy-Prosper Enfantin (1796 –1864) came into conflict with French authorities due to its controversial free-love practices, but not all Saint-Simonians were counter-cultural eccentrics. Many played an active role in the 1830 Revolution that brought the July Monarchy to power and remained influential — particularly as financiers and industrialists — under the Second Empire (1852–1870). See Pamela Pilbeam, Saint-Simonians in Nineteenth-Century France: From Free Love to Algeria (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013).

- Journal du commerce, February 14, 1831; La France nouvelle, February 12, 1831.

- Alexandre Dumas fils, “Preface à Un Père Prodigue,” in Théatre Complet de Alexandre Dumas Fils, vol. 3 (Paris: Michel Lévy Frères, 1868), 201.

- Aimé Dolfus and Édouard Drumont, Je déjeune a midi: Pièce en un acte (Paris: Michel Lévy, 1875).

- Rising to international notoriety in 1868 with his one-man satirical weekly La Lanterne, which at its peak had a readership of over 120,000, Rochefort was briefly involved in the Paris Commune and sentenced to deportation in the penal colony of New Caledonia in 1873. He returned to France in 1880 as an amnestied ex-Communard and became editor-in-chief of L’Intransigeant, an independent radical-socialist daily that specialised in anti-corruption crusading. Turning increasingly against representative democracy as practiced under the Third Republic, Rochefort allied himself with authoritarian adventurers like General Georges Boulanger and far-right antisemites in the 1880s and 90s. During the Dreyfus Affair, he became one of the main anti-Dreyfusard polemicists.

- Théodore Muret, L’Histoire par le théâtre, 1789-1851: Le Gouvernement de 1830, la seconde République (Paris: Amyot, 1865), 193–4.

- Le Figaro, June 26, 1832.

Public Domain Works

- Les pilules dramatiques, ou le choléra-morbus, M. Le Docteur Mesenthère (1831)

- Mémoire sur le choléra-morbus, Dominique-Jean Larrey (1831)

- L’Histoire par le théâtre, 1789-1851, Théodore Muret (1865)

Further Reading

- A History of the Barricade, by Eric Hazan

- Disease and Civilization: The Cholera in Paris, 1832, by François Delaporte, translated by Arthur Goldhammer