The expulsion of 1290 stands as a warning about the fragility of pluralism when tolerance is not grounded in principle but in convenience.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Difference, Law, and the Anxiety of Coexistence

In medieval England, Jewish communities occupied a paradoxical position within the legal and social order. They lived under the direct authority of the English crown, enjoyed periods of royal protection, and participated in the economic life of the realm, yet they also governed many of their internal affairs according to Halakha, Jewish religious law. This arrangement was neither clandestine nor revolutionary. It was a recognized feature of medieval governance, one instance of a broader pattern of legal pluralism that characterized European societies long before the rise of centralized, uniform legal systems. For much of the twelfth century, this coexistence was tolerated, if uneasy.

Jewish law in England was explicitly limited in scope and clearly bounded by royal authority. It governed internal communal matters such as marriage, inheritance, ritual observance, education, and the resolution of disputes among Jews. It did not claim authority over Christians, nor did Jewish courts seek to compete with royal or ecclesiastical jurisdiction. Christian courts retained supremacy in cases involving Christians, mixed parties, or questions of public order. The English legal system itself acknowledged and regulated this separation, permitting Jewish communities a measure of autonomy while affirming the crown’s ultimate sovereignty. In practice, Jewish self-governance functioned as an administrative convenience and a stabilizing mechanism, allowing communities to manage internal affairs without burdening royal courts or undermining Christian legal supremacy.

Yet over the course of the thirteenth century, this tolerated difference increasingly came to be perceived as a problem rather than a pragmatic accommodation. Christian authorities, clerical writers, and popular discourse began to frame Jewish separateness not as a manageable exception, but as a latent danger embedded within the social body. The concern was not that Jewish law was being imposed on Christians, a charge never seriously advanced, but that Jews lived according to a law not shared by the majority. Legal distinctiveness itself became suspect. Communal autonomy was reimagined as secrecy, internal cohesion as conspiracy, and adherence to Halakha as refusal of loyalty to the Christian realm. What had once been accepted as pluralism was gradually recast as subversion, not through evidence of legal overreach, but through fear of enduring difference.

The crisis surrounding Jewish law in medieval England was not a conflict over jurisdiction, but an anxiety about coexistence. Jewish self-governance through Halakha challenged emerging expectations of legal and cultural uniformity in a Christian polity increasingly uncomfortable with internal difference. The eventual expulsion of Jews in 1290 was not the result of Jewish legal aggression, but the resolution of a narrative in which minority self-governance itself had become intolerable. The transformation of lawful difference into perceived threat reveals the fragility of medieval pluralism when confronted with fear, economic stress, and ideological consolidation.

Jews in Medieval England: Status, Protection, and Royal Authority

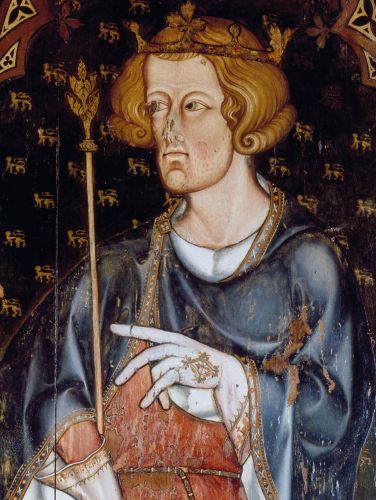

From the Norman Conquest onward, Jews in England occupied a distinct legal category defined by their relationship to the crown. Classified as servi camerae regis, they were considered dependents of the royal chamber, a status that simultaneously exposed them to exploitation and afforded them protection. This designation placed Jewish communities outside the ordinary structures of feudal obligation while binding them directly to royal authority. Their presence in England was never a matter of customary tolerance alone, but a function of royal policy grounded in fiscal and administrative calculation.

Royal protection was not abstract. Kings extended charters that guaranteed Jewish residence, regulated lending practices, and authorized communal organization. In return, Jewish communities provided essential financial services in a Christian society where canon law restricted usury. This arrangement made Jews economically useful and legally exceptional. Their protection depended less on moral commitment to pluralism than on the crown’s interest in maintaining a reliable source of revenue and credit. Jewish security was always conditional, contingent on continued royal advantage rather than inherent rights.

This dependency produced a paradoxical form of autonomy that was both real and fragile. Because Jews were under direct royal jurisdiction, local lords, borough courts, and ecclesiastical authorities were often restricted from intervening in Jewish internal affairs. Jewish courts could adjudicate disputes among Jews, religious authorities could enforce communal norms, and synagogues and schools could operate openly under royal license. This autonomy was practical rather than ideological. It existed because it simplified governance and reduced administrative burden on royal institutions. Jewish self-governance was tolerated precisely because it posed no challenge to royal supremacy and because it localized regulation within the community itself, keeping internal conflicts contained.

At the same time, royal authority over Jews was absolute and unmediated, lacking the customary restraints that protected Christian subjects. Jews possessed no estate-based privileges, no access to common law protections independent of the crown, and no institutional buffer against royal intervention. The king could tax Jewish communities arbitrarily, seize property, imprison community leaders, or revoke protections without meaningful procedural limitation. Periods of protection were frequently punctuated by episodes of intense extraction, including forced loans, mass arrests, and confiscation of assets. Legal dependence functioned simultaneously as shield and exposure, reinforcing Jewish distinctiveness while rendering that distinctiveness dangerously contingent on royal favor.

As royal finances grew strained in the thirteenth century, the instrumental logic underlying Jewish protection began to erode. Alternative credit mechanisms expanded, Christian lenders increasingly filled financial roles once dominated by Jews, and parliamentary consent placed new constraints on royal taxation. Jewish communities, once valued as fiscal assets, came to be perceived as politically costly and economically redundant. Royal authority over Jews, previously framed as guardianship, hardened into possession, enabling harsher regulation and more aggressive extraction. Protection weakened not because Jewish law posed a threat, but because the crown’s incentive to sustain Jewish presence diminished.

This transformation set the conditions for a broader reimagining of Jewish status within English society. Once royal protection faltered, Jewish legal autonomy lost its stabilizing function and became increasingly visible as difference without justification. What had been tolerated as a regulated exception under royal authority was now exposed to hostile reinterpretation by clerical writers, civic authorities, and popular rumor. Jewish separateness, long sustained by the crown’s interest, became politically vulnerable once that interest waned. The legal status that had enabled coexistence also laid the groundwork for its collapse, turning dependency into exposure and autonomy into accusation.

Halakha and Internal Jewish Self-Governance

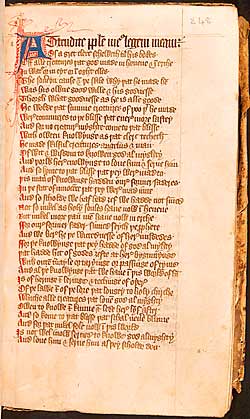

Within medieval England, Jewish communities governed their internal affairs through Halakha, a comprehensive religious legal system that regulated ritual life, family relations, education, charity, and dispute resolution among Jews. This legal autonomy was neither hidden nor subversive. It was an openly recognized feature of Jewish communal life, operating within boundaries acknowledged by royal authority. Halakhic courts adjudicated matters that Christian law neither sought nor wished to manage, allowing Jewish communities to maintain internal order without encroaching on the jurisdiction of royal or ecclesiastical courts.

Halakha did not claim authority beyond the Jewish community, and its jurisdictional limits were well understood by both Jewish and Christian authorities. Jewish courts exercised no power over Christians, and cases involving mixed parties, serious criminal matters, land tenure, or questions of royal interest were routinely transferred to English courts. There was no attempt to substitute Halakhic rulings for royal law in public life. Instead, Halakhic governance functioned as a parallel but carefully bounded system, addressing matters such as marriage contracts, inheritance among Jews, commercial disputes within the community, and obligations rooted in religious practice. Far from undermining English sovereignty, this arrangement reinforced it by localizing governance, reducing legal ambiguity, and minimizing friction between minority communities and the crown.

Jewish self-governance also relied on communal institutions such as synagogues, councils of elders, and learned legal authorities who interpreted and applied Halakha. These institutions provided social cohesion and moral regulation in a context where Jews were excluded from Christian guilds, courts, and civic offices. Legal autonomy was not an assertion of separatist ambition but a practical necessity imposed by exclusion. Halakha allowed Jewish communities to function as ordered societies within a hostile or indifferent majority culture, ensuring continuity without challenging external authority.

The existence of Halakhic self-governance nevertheless became increasingly unsettling to Christian observers as broader attitudes toward difference hardened in the thirteenth century. What had once been accepted as a bounded legal autonomy came to be interpreted as evidence of inwardness, secrecy, and refusal to assimilate. Jewish law was not condemned for jurisdictional overreach but for its persistence across generations. Its endurance marked Jews as a community governed by norms not shared by their neighbors, and this difference alone became sufficient to provoke suspicion. Internal self-regulation, once tolerated as administrative convenience and even as a stabilizing feature of royal governance, was gradually recast as a sign of dangerous separateness, transforming lawful autonomy into a perceived moral and social threat.

Christian Legal Thought and the Problem of “Separate Law”

Christian legal thought in medieval England was shaped by assumptions of universal moral order rooted in divine law and reinforced by ecclesiastical authority. While medieval Christian societies accommodated a range of local customs and inherited practices, there was an underlying expectation that legitimate law ultimately reflected Christian truth and hierarchy. Jewish legal autonomy occupied an uneasy and increasingly fragile position. Although Halakha did not challenge royal or ecclesiastical jurisdiction directly, its existence as a self-contained legal system grounded in a non-Christian theological framework unsettled assumptions about unity, moral coherence, and sovereignty within a Christian polity moving toward tighter ideological consolidation.

Canon law in particular struggled to conceptualize enduring legal pluralism. Jewish law was tolerated as a concession to circumstance rather than affirmed as a legitimate parallel system. Christian jurists increasingly framed Jewish legal difference as a provisional exception that ought not to persist indefinitely. The concern was not that Jewish courts were issuing rulings harmful to Christians, but that a community governed by its own sacred law existed outside the universal reach of Christian moral authority. Legal separateness came to be associated with spiritual error, even when its practical effects were limited and regulated.

This discomfort intensified as Christian legal thought became more systematized in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. The revival of Roman law, the rise of scholastic method, and the growing ambition to organize law into coherent, hierarchical systems encouraged the belief that legitimate authority should be comprehensive and internally consistent. In this intellectual climate, plural legal systems appeared increasingly anomalous rather than pragmatically useful. Jewish law, precisely because it was coherent, durable, and internally authoritative, could be perceived as a rival normative order, even when it claimed no jurisdiction beyond the Jewish community. What had once been managed as difference was now reinterpreted as contradiction.

The problem of “separate law” was conceptual rather than practical. Jewish legal autonomy challenged emerging Christian expectations that moral authority should be unified under Christian governance. Living under a different law suggested resistance to incorporation, even when no political defiance existed. Difference was interpreted as disobedience, and continuity as defiance. The endurance of Halakha became troubling not because of what it did, but because of what it symbolized: the persistence of a non-Christian moral universe within a Christian realm.

Christian legal discourse increasingly reimagined Jewish law as a latent threat to social and spiritual order. This shift did not arise from concrete jurisdictional conflict, but from anxiety about the limits of tolerance itself. Minority self-governance, once administratively convenient and legally contained, was reframed as evidence of disloyalty and inwardness. The longer Jewish law endured without assimilation, the more it appeared incompatible with Christian ideals of unity. In this transformation, lawful coexistence gave way to suspicion, and tolerance eroded into exclusion, setting the intellectual groundwork for persecution and eventual expulsion.

From Tolerated Difference to Accusation of Subversion

The transition from uneasy tolerance to active suspicion in medieval England did not occur suddenly, nor was it driven by a single catalytic event. It unfolded gradually as social, economic, and theological pressures converged over the course of the thirteenth century. Jewish difference, once managed through royal authority and bounded legal autonomy, began to be reinterpreted through a lens of moral anxiety rather than administrative pragmatism. Practices that had long been visible and regulated were recast as hidden, and separateness itself became a source of fear. The shift was less about any change in Jewish behavior than about a change in Christian perception of difference.

One mechanism through which this transformation occurred was narrative. Rumors, accusations, sermons, and polemical literature increasingly portrayed Jewish communities as secretive, inward-facing, and internally coordinated in ways that threatened Christian society. Legal autonomy, once understood as a practical necessity under royal oversight, was reframed as evidence of concealment and moral distance. Jewish courts, communal councils, and learned authorities, previously acknowledged as limited and regulated institutions, became objects of suspicion precisely because they operated according to norms inaccessible to Christians. The fact that Halakha governed only Jewish life was increasingly overshadowed by the anxiety that Jews lived by rules unknown, unshared, and untrustworthy in the eyes of the majority.

Economic tension amplified these suspicions. As Jewish lending became more politically fraught and less economically indispensable, resentment hardened into moral condemnation. Debt relations, once regulated through royal law and Jewish communal mechanisms, were reinterpreted as exploitation and malice rather than structural necessity. Legal protections extended to Jewish financiers came to be depicted as unjust privileges that insulated wrongdoing. Jewish reliance on internal legal structures to manage contracts, obligations, and disputes reinforced the perception of separateness, making legal autonomy appear not as governance but as evasion. What had been a regulated economic role under royal oversight was now imagined as a coordinated threat operating behind legal boundaries.

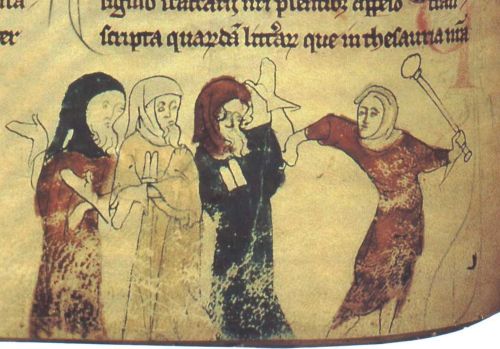

These developments found their most extreme expression in increasingly fantastical accusations, including blood libel and host desecration myths. Such charges bore no relation to Jewish legal practice, yet they drew rhetorical power from the idea that Jews were governed by secret laws and hidden intentions. Legal difference was transformed into moral otherness, and moral otherness into imagined criminality. The accusation was never that Jews sought to impose their law on Christians, but that living under a different law rendered Jews fundamentally alien, opaque, and capable of acts beyond Christian comprehension. Myth thrived precisely where legal reality was ignored.

By the late thirteenth century, the narrative of Jewish subversion had hardened into political consensus. Jewish self-governance was no longer interpreted as a contained exception within royal authority, but as proof of irreconcilable difference. Minority legal autonomy, once tolerated as pragmatic governance, was now cast as an obstacle to social cohesion and Christian unity. Accusation replaced accommodation, and suspicion displaced regulation. In this climate, expulsion emerged not as an aberration or sudden rupture, but as the logical resolution of a fear that difference itself had become intolerable.

Law, Loyalty, and the Limits of Medieval Pluralism

Medieval England’s accommodation of legal difference operated within narrow and inherently unstable limits. Pluralism was tolerated only so long as it could be framed as temporary, contained, and securely subordinate to Christian sovereignty. Jewish self-governance through Halakha was acceptable not as a recognized right, but as a managed exception justified by royal interest and administrative convenience. Once difference ceased to appear provisional and instead revealed itself as enduring and self-sustaining, the conceptual foundations of coexistence began to erode. Pluralism, in this sense, was never an ethical commitment to diversity but a conditional arrangement dependent on confidence in control and the belief that difference would not persist indefinitely.

At the heart of this fragility was the increasing fusion of law and loyalty in Christian political thought. Law was no longer understood merely as a mechanism of order but as a marker of moral allegiance. To live under Christian law was to belong to the Christian polity in a meaningful sense. Jewish adherence to Halakha, even when limited to internal matters, came to be interpreted as evidence of divided loyalty. The issue was not competing jurisdictions, but competing normative worlds. Legal difference suggested moral distance, and moral distance was increasingly equated with political unreliability.

This shift reflected broader transformations in medieval governance. As royal authority expanded and legal systems grew more centralized, tolerance for enduring legal plurality diminished. The expectation emerged that legitimate subjects should be governed not only by the same ruler but by the same law. Difference, once manageable through delegation and exemption, now appeared as a failure of integration. Jewish legal autonomy became emblematic of a broader anxiety about the limits of governance in a society striving for cohesion through uniformity.

The fate of Jewish self-governance in medieval England illustrates the structural limits of medieval pluralism with particular clarity. Law could accommodate difference only so long as that difference remained economically useful and ideologically tolerable. When royal interest waned and theological confidence hardened into exclusivity, pluralism collapsed. Jewish law was not rejected because it threatened Christian law in practice, but because its persistence exposed the difficulty of sustaining coexistence without sameness. Minority self-governance was redefined as disloyalty, lawful difference became evidence of subversion, and exclusion emerged as the political solution to a society unwilling to tolerate enduring plurality.

Expulsion as Resolution, Not Accident

The expulsion of Jews from England in 1290 was not a sudden rupture or an irrational departure from earlier policy. It was the culmination of decades of legal, economic, and ideological transformation that steadily narrowed the space for Jewish presence. By the late thirteenth century, coexistence had already been hollowed out. Royal protection had weakened, economic utility had declined, and Jewish legal autonomy had been reframed as evidence of dangerous difference. Expulsion did not interrupt an otherwise stable arrangement. It resolved a tension that medieval English society had come to regard as intolerable.

From the perspective of royal governance, expulsion offered a definitive administrative solution to a problem that had grown increasingly burdensome. Jewish communities had long been managed through exceptional legal status, direct taxation, and special judicial mechanisms that required constant royal intervention. As these structures grew politically costly and fiscally less productive, they ceased to justify continued protection. The crown no longer derived sufficient advantage from sustaining a legally distinct population that demanded protection while attracting hostility from nobles, towns, and clergy. Removing the population altogether eliminated the need to manage difference, enforce exceptional safeguards, or defend pluralism in an environment increasingly hostile to its premises.

Ideologically, expulsion aligned with a growing insistence on legal, cultural, and moral uniformity within the English realm. By the end of the thirteenth century, English Christian identity had become more tightly bound to shared law, shared faith, and shared moral norms. Jewish adherence to Halakha, once tolerated as a bounded exception under royal authority, now appeared incompatible with these expectations. The persistence of Jewish law symbolized the failure of assimilation, not because Jews resisted English sovereignty, but because they remained governed internally by norms not shared by the majority. Expulsion functioned as a means of restoring imagined coherence to the social order by removing a form of difference that could no longer be ideologically reconciled.

Popular hostility played a reinforcing role, but it did not drive policy independently. Accusations of ritual crime, economic exploitation, and moral corruption had circulated for decades, shaping public perception of Jews as inherently suspect. These narratives did not emerge spontaneously in 1290. They had been cultivated through sermons, rumor, and legal rhetoric that increasingly framed Jewish separateness as threat. By the time expulsion was enacted, it could be presented not as innovation, but as response to a danger already assumed to exist.

Expulsion did not rest on the claim that Jews had violated English law or attempted to impose their own law on Christians. The charge was not legal aggression but incompatibility. Jewish law had remained internal, regulated, and subordinate to royal authority. What changed was not Jewish practice, but Christian tolerance for legal difference. Expulsion addressed this perceived incompatibility by removing the community rather than negotiating coexistence. Law did not adjudicate difference. It erased it.

Expulsion was not an aberration but the logical endpoint of a system that had never fully accepted pluralism as permanent. Jewish legal autonomy had been tolerated only so long as it served royal interests and remained ideologically manageable. Once it ceased to do so, exclusion replaced regulation. The removal of Jews from England resolved the anxiety produced by minority self-governance by eliminating the minority itself. Expulsion stands not as a tragic accident of medieval politics, but as a deliberate resolution by a society unwilling to sustain lawful difference.

Conclusion: Minority Self-Governance Recast as Subversion

The history of Jewish self-governance in medieval England demonstrates that legal difference was not rejected because it produced conflict, but because it endured. Halakha never challenged royal or ecclesiastical authority, never claimed jurisdiction over Christians, and never sought to replace English law. For decades, it functioned as a regulated, bounded system that allowed Jewish communities to manage internal affairs within a framework of royal sovereignty. What ultimately provoked hostility was not legal overreach, but the continued existence of a minority governed by norms not shared by the majority. Difference itself became the problem.

This transformation reveals the conditional nature of medieval pluralism. Legal autonomy was tolerated only so long as it could be justified as temporary, economically useful, or ideologically manageable. Once royal interest declined and Christian political identity hardened around expectations of uniformity, pluralism lost its protective logic. Jewish law ceased to appear as an administrative convenience and came to symbolize resistance to incorporation, even when no such resistance existed. Minority self-governance was recast as refusal, endurance as defiance, and continuity as threat.

The reframing of Jewish legal autonomy as subversion did not require evidence of disloyalty or legal aggression. It relied instead on narrative, suspicion, and the collapsing of difference into danger. Law became a proxy through which anxiety about coexistence could be expressed in juridical terms. By treating internal self-regulation as evidence of secrecy or conspiracy, Christian society transformed lawful difference into moral offense. The accusation was never that Jews imposed their law on others, but that living differently under law was intolerable within an increasingly uniform Christian polity.

The expulsion of 1290 stands as a warning about the fragility of pluralism when tolerance is not grounded in principle but in convenience. Medieval England did not fail to manage legal diversity because such diversity was unworkable, but because it lacked the conceptual and moral commitment to sustain it. Minority self-governance was not defeated by law, but by fear. When difference could no longer be accommodated, it was redefined as subversion and removed. In this outcome, medieval England exposed the enduring danger that lawful coexistence can collapse when societies mistake endurance for threat and autonomy for disloyalty.

Bibliography

- Bartlett, Robert. The Making of Europe: Conquest, Colonization and Cultural Change, 950-1350. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993.

- Baumgarten, Elisheva. “Jewish Belonging in Medieval Europe: Challenges and Possibilities.” The Medieval History Journal 27:2 (2024), 287-297.

- Chazan, Robert. Medieval Jewry in Northern France: A Political and Social History. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987.

- Grossman, Avraham. The Early Sages of Ashkenaz. Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1988.

- Hillaby, Joe. “The London Jewry: William I to John.” Jewish Historical Studies 33 (1992-1994), 1-44.

- Langmuir, Gavin I. History, Religion, and Antisemitism. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991.

- —-. Toward a Definition of Antisemitism. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990.

- Moore, R. I. The Formation of a Persecuting Society: Authority and Deviance in Western Europe, 950–1250. Oxford: Blackwell, 1987.

- Mundill, Robin R. England’s Jewish Solution: Experiment and Expulsion, 1262–1290. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Reilly, Rebecca Colleen. “Changes in Attitudes Towards Jews in Twelfth- and Thirteenth-Century England.” Elements 14:1 (2018).

- Roth, Pinchas. “Jewish Courts in Medieval England.” Jewish History 31:1/2 (2017), 67-82.

- Rubin, Miri. Gentile Tales: The Narrative Assault on Late Medieval Jews. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999.

- Southern, R. W. The Making of the Middle Ages. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1953.

- Stacey, Robert C. “Jewish Lending and the Medieval English Economy.” In A Commercialising Economy? England 1000-1300, Richard Britnell and Bruce Campbell, eds. Princeton: Princeton University Press (1994), 78-101.

- Wiedemann, B. “Papal legates, Jews and the Fourth Lateran Council in England, 1215–1221.” Jewish Historical Studies: A Journal of English-Speaking Jewry 56:1 (2025), 79-99.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.13.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.