Vladimir Ilyich Lenin addressing a crowd during the Russian Revolution of 1917. / Wikimedia Commons

By Dr. Lewis Siegelbaum / 12.28.2015

Professor of Russian and European History

Michigan State University

EVENTS

February Revolution

Aleksei Radakov: The Autocratic System (1917) / From Building the Collective: Soviet Graphic Design, by Leah Dickerman

More than three centuries of Romanov dynastic rule came to an end in late February 1917 when striking workers and mutinous soldiers in Petrograd forced tsar Nicholas II to abdicate the throne. The Revolution began on February 23 (March 8 NS) when working-class women, observing the socialist holiday of International Women’s Day, took to the streets of the capital to protest against food shortages and high bread prices. This was not the first of such protests during the war, but over the next several days, encouraged by calls from activists in the revolutionary underground (including Bolsheviks), crowds of both men and women swelled and marched to the center of the city. There, units of the regular police as well as Cossacks and soldiers from the Volhynian regiment attempted to disperse them but with limited success. Indeed, by February 27, with Petrograd at a virtual standstill, key military units went over to the side of the crowds, seized arsenals of weapons, and on the following day placed the tsarist ministers under arrest. The tsar, who had taken personal command of the army, sought to return to Petrograd to restore the status quo ante, but was persuaded by his own generals and a delegation of politicians from the State Duma that only his abdication could achieve social peace.

Petrograd Municipal Duma: Revolution in Petrograd! (1917) / Hoover Political Poster Database

On March 2 the provisional committee of the State Duma, consisting of leading moderate and liberal politicians, declared itself a Provisional Government. When the crowd outside the Tauride Palace taunted Pavel Miliukov, the leading politician of the Kadet (Constitutional Democratic) Party and the first Minister of Foreign Affairs in the Provisional Government, with cries of “Who elected you?” his response was “We were elected by the Russian Revolution.” But as suggested by its very name, the new government’s authority was limited, and from the outset it was acknowledged that only a popularly elected Constituent Assembly could decide the political structure of the country. Moreover, simultaneous with the government’s formation, the socialist parties (Bolsheviks, Mensheviks, and Socialist Revolutionaries) called upon workers and soldiers to elect deputies to soviets. In Petrograd the Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies formed an Executive Committee which met in almost continual session. Initially dominated by Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries, the Executive Committee determined its main purpose to be the defense of “democracy” for which it extended support to the “bourgeois” Provisional Government on a conditional basis. Soviets soon emerged in other cities and eventually in rural areas as well.

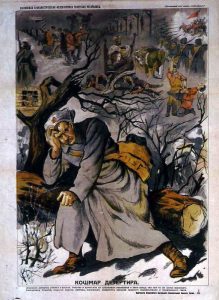

Nightmare of the Deserter (1919) / Hoover Political Poster Database

The overthrow of tsarism was greeted with popular acclaim. The loss of effective state authority gave the public unprecedented freedom of assembly and expression and resulted in the establishment of new newspapers, political organizations, trade unions, and other institutions of civil society. These, the halcyon days of the revolution, lasted about a month. During this time, the Provisional Government, guided by the spirit of political liberalism, issued a stream of decrees covering education, labor relations, religious affairs, and other spheres of public life. With respect to food shortages, it felt compelled to establish a state grain monopoly to be administered by elaborate hierarchy of provisioning committees under a Ministry of Food Supply. However, on the main, “burning” questions of Russia’s continued participation in the war, and land reform, the government either confined itself to setting up committees to study the question or deferred any decision until the convocation of the Constituent Assembly. In retrospect, it is easy to see this relative inaction as having fatally undermined the Provisional Government.

Formation of the Soviets

Valentin Serov: Lenin Proclaims the Victory of the Revolution (November 8, 1917) to Second All-Russia Congress of Soviets / FUNET Image Archive

When some thirty to forty socialist intellectuals and workers gathered in the Tauride Palace on the afternoon of February 27, 1917 to attempt to provide leadership to the revolution already happening in the streets of the capital, they harked back to the Soviet of Workers’ Deputies thrown up by the 1905 Revolution. Declaring themselves a Temporary Revolutionary Committee of the Soviet of Workers’ Deputies, they appealed to workers and soldiers to send representatives to a meeting called for that evening. By about nine o’clock, approximately 250 workers, soldiers and socialist intellectuals had assembled. They chose Nikolai Chkheidze, a Menshevik Duma deputy, as chairman, and two other socialist Duma deputies, Mikhail Skobelev and Aleksandr Kerenskii, as vice-chairmen. They also elected an Executive Committee comprised mainly of intellectuals. Thus was born the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ (and from March 1, Soldiers’) Deputies.

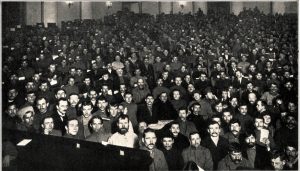

Left: Third All-Russian Congress of Soviets (1917) / From An Illustrated History of the Russian Revolution, by Valentin Astrov

Right: Provisional Executive Committee of the Soviets – First Manifesto of the Soviets of Workers Deputies (1917) / From An Illustrated History of the Russian Revolution, by Valentin Astrov

In Moscow, the process was almost identical. The first meeting of the Moscow Soviet of Workers’ Deputies on March 1 was attended by 52 delegates from factories, cooperative societies and trade unions. After electing an Executive Committee of 44 members (!), the meeting adjourned until the evening by which time over six hundred delegates had assembled. L. M. Khinchuk, a Menshevik, was elected chairman of the Executive Committee and like Chkheidze in Petrograd, served in this position until the Bolsheviks obtained a majority in September.

Who is Against the Soviets? (1917-1922) / Hoover Political Poster Database

Both in Moscow and Petrograd, as indeed elsewhere in the country, the soviets initially were dominated by moderate socialists who coordinated their activities with the Committees of Public Safety and other bodies constitutive of the Provisional Government. Yet, as organs dedicated to defending the interests of workers and soldiers, they implicitly challenged the claim of the Provisional Government to be above class. This situation of dual power (dvoevlastie) thus proved inherently unstable, despite the intentions of the soviets’ leaders to merely secure the revolution rather than driving it forward.

April Crisis

Arkadii Viktorovich Rusin: Lenin’s Arrival at the Finland-Station in 1917 / 1970 Painting by Werner Horvath, Political Art Gallery

The euphoria of the February Revolution did not last long. Within weeks of the overthrow of the tsar, the continued, indeed intensified, deterioration of economic life was roiling the population. With inflation beginning to spiral out of control, agreements concluded between nascent trade unions and employers rapidly became moot as wage increases were nullified by rising prices. Factory owners as well as the landed nobility tended to look to the Provisional Government to protect them from the rising tide of worker and peasant demands. Workers organized factory committees to press their case for workers’ control of factory administration and sought the support of the soviets; peasants petitioned the Provisional Government for revision of land ownership and when they received no effective reply, began to organize rent strikes and even seizures of landowners’ property.

Lenin speech at the Tauride Palace in Petrograd (April 1917) / Marxists Internet Archive

Over and above these economic issues, though, was the question of Russia’s participation in the war, which was widely blamed for its economic miseries. The Petrograd Soviet brought pressure on the Provisional Government by issuing an “Appeal to All the Peoples of the World” on March 14 that repudiated expansionist war aims in the name of “revolutionary defensism.” The government responded on March 27 with a “Declaration on War Aims” that also rejected annexations and indemnities as war aims but contradictorily asserted the need to observe treaty obligations. In the midst of these tensions between the two central institutions of “dual power,” Vladimir Lenin arrived in Petrograd on April 3 aboard a sealed train that had taken him from Switzerland through Germany. At the Finland Station he issued a speech denouncing both positions and demanding the elimination of dual power by the transfer of “all power to the soviets.” These so-called April Theses clearly set the Bolsheviks apart from the other socialist parties, and it took all of Lenin’s considerable persuasive powers to overcome opposition among those who had been guiding the party in his absence.

Statue of Lenin at Finland-Station / FUNET Image Archive

The dispute over Russia’s war aims exploded into a full-blown political crisis after the publication of a note that the Foreign Minister, Pavel Miliukov, had sent to the allies on April 18 reaffirming the Provisional Government’s commitment to prosecute the war to a victorious end and observe all treaties entered into by its tsarist predecessor. Mass demonstrations and clashes on the streets of Petrograd forced both Miliukov and the War Minister, Aleksandr Guchkov, to resign. The Provisional Government thereupon invited the Petrograd Soviet to help form a coalition government consisting of both socialist and non-socialist leaders, an invitation that the Soviet Executive Committee accepted with reservations. On May 5, five additional socialists including the Socialist-Revolutionary, Victor Chernov, and the Mensheviks Irakli Tseretelli and Mikhail Skobelev, joined Kerenskii in government. This had two critical consequences: the lines of dual power became considerably blurred, and the two main socialist rivals of the Bolsheviks now were inextricably associated with the policies of the Provisional Government and above all, its continued prosecution of the war.

Revolution in the Army

Left: Lieutenant-General M.V. Aleksieev (1914), by I.D. Sytin Lithography / Hoover Political Poster Database

Right: Lieutenant-General A.A. Brusilov (1914), by I.D. Sytin Lithography / Hoover Political Database

At the time of the February Revolution, the Imperial Russian Army contained some seven and a half million soldiers who were overwhelmingly drawn from the peasantry. The most immediate and tangible effect of the Revolution on the army was Order No. 1 issued by the Executive Committee of the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies on March 1, 1917 and approved under duress by the Provisional Government. Among other things, the Order called for the election of soldiers’ committees under whose disposal all arms were to be placed. Although they were to maintain “the strictest military discipline,” soldiers were to enjoy the rights of all citizens outside the service and the ranks. They also were no longer to be addressed by their officers in the familiar (and condescending) form of “you” (ty). The addressing of officers with titles such as “your Excellency” was abolished and replaced by “Mister General,” “Mister Colonel,” etc.

Left: Aleksandr Kerenskii at the Western Front in World War I (1917)

Right: Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies Order No. 1 (March 1, 1917) / From An Illustrated History of the Russian Revolution, by Valentin Astrov

The first few weeks of the revolution witnessed the desertion of between 100,000 and 150,000 soldiers, most of whom were peasants anxious to return to their villages to participate in what they expected would be a division of the land. There was also a substantial tide of arrests of officers, particularly senior commanders, and their replacement by more popular individuals. Instances of violence, including executions of officers, were recorded in the Baltic Fleet and in the Petrograd garrison, but were relatively rare at the front. In his report of April 16, General Alekseev, the Commander in Chief of the armed forces, complained that “the army is systematically falling apart,” a situation that he attributed to the spread of “defeatist literature and propaganda.” But what is no less striking about the revolution in the army is the extent to which rank-and-file soldiers justified their actions in the patriotic terms of defending a “free Russia.”

Left: Boris Kustodiev – Freedom Loan (1917) / From Persuasive Images: Posters of War and Revolution from the Hoover Institution Archives, by Peter Paret and Beth Irwin

Right: Sketch of Aleksandr Kerenskii, by Iurii Annekov (1917) / Inter-Language Literary Associates

Whatever the case, Aleksandr Kerenskii, who had replaced Aleksandr Guchkov as Minister of the Army and Navy in May, became convinced that Russia either had to accept the virtual demobilization of the army and capitulate to Germany or assume the initiative in military operations. Touring the fronts, he sought to whip up enthusiasm for an offensive that he and the leading core of officers hoped would ignite patriotic fervor and bring victory to revolutionary Russia. The offensive, under General A. A. Brusilov, began on June 18 all along the southwestern front. After some initial successes, the Russian army’s advances were repulsed, and the desperate attempt to stem the tide of the army’s disintegration actually served to accelerate it.

July Days

Petrograd, July 4, 1917 / Photo by K. Bulla, Wikimedia Commons

“You have come here, you, red men of Kronstadt, as soon as you heard about the danger threatening the revolution … Long live red Kronstadt, the glory and pride of the revolution!” Thus did Leon Trotsky harangue and flatter the soldiers and sailors who amassed before the Tauride Palace to attempt to force the Executive Committee of the Petrograd Soviet to seize power from the Provisional Government. The armed demonstration which included soldiers from the Petrograd garrison and factory workers began on the evening of July 3 and lasted until the morning of the fifth.

Left: Petrograd street demonstration (1917) / Wikimedia Commons

Right: Rally at Putilov Factory (1917) / From Through the Russian Revolution, by Albert Rhys Williams

The soldiers and sailors of Kronstadt were among the most militant in the Russian armed forces. In February they had executed some forty officers including the base commander, Admiral R. N. Viren. They had figured prominently in the Petrograd street demonstrations of April and June. In May, the Kronstadt soviet had declared itself the sole authority on the island and endorsed Lenin’s call for “all power to the soviets.” Now in July, they sought to realize that demand, at one point taking captive Victor Chernov, the SR Minister of Agriculture in the Provisional Government, whom they regarded as a traitor to the revolution.

Meeting of the Bolsheviks Military Committee (1917) / From An Illustrated History of the Russian Revolution, by Valentin Astrov

The Bolshevik leadership, including Lenin who had just returned to Petrograd from Finland, was fundamentally ambivalent about the demonstration. While the Central Committee advised caution lest the demonstration provoke a counter-revolutionary thrust, the party’s Military Organization and Petersburg Committee publicly endorsed it and summoned reinforcements from the front. But at the same time, the Executive Committee of the Soviet, still dominated by Mensheviks and SRs, also called up troops to disperse the demonstrators. Moreover, the Provisional Government, in a desperate attempt to undermine the Bolsheviks’ credibility, decided to go public with its investigation of their receipt of German money and charges that Lenin was a German spy. These actions combined to quell the rebellion.

Left: Comrade Soldiers and Workers! (1917) / Hoover Political Poster Database

Right: To the Workers of Petrograd! (1917) / Hoover Political Poster Database

There exists no film footage of the July Days. But ten years later, Sergei Eisenstein’s dramatization of the revolution, October, included what was to become one of the most famous scenes of Soviet cinema in which the demonstrators scatter as they are fired upon from the rooftops.

Kornilov Affair

Left: General Lavr Georgievich Kornilov (1917) / Hoover Political Poster Database

Right: General Lavr Georgievich Kornilov waving to a Moscow crowd from a limousine (1917) / Wikimedia Commons

The July Days did not end the revolution’s summer of discontent. On the one hand, the propertied classes’ fears of chaos and disorder from below seemed to have been realized; on the other, the Provisional Government, now led by Aleksandr Kerenskii and galvanized into action against the Bolsheviks, seemed less likely than ever to alleviate the economic distress and social resentment among the lower classes. While factory management frequently responded to rising costs and loss of control over workers by curtailing or even shutting down operations, workers increasingly resorted to strikes, physical attacks against foremen and other line supervisors, and occupations of factory grounds. The breakdown of food and fuel distribution systems had ripple effects throughout the entire economy and society. Crime and acts of violence rose dramatically as unruly bands of armed deserters roamed through the streets and railroad stations. In the countryside, peasant land seizures went unpunished. Further afield, in some of the national minority areas, separatist movements gathered pace, while in the northwest the German army was advancing. As class polarization became more manifest and conspiracy theories proliferated, the whole country seemed to be falling apart. “Chaos in the army, chaos in foreign policy, chaos in industry and chaos in the nationalist questions” was the way Pavel Miliukov, the Kadet Party leader, summed up the situation in late July.

Don’t Believe the Whispers! (1917) / Hoover Political Poster Database

These, then, were the circumstances in which General Lavr Kornilov, appointed Supreme Commander of the Russian armed forces on July 18, appeared as a savior to many who longed for an end to the revolutionary “chaos.” Those who backed his candidacy for the role of military dictator included several key politicians from the conservative and centrist parties, top military personnel, and banking and industrial leaders associated with the Society for the Economic Rehabilitation of Russia and the Republican Center. Lauded as a hero after his escape from a Hungarian prisoner-of-war camp and return to Russia in 1916, Kornilov held the Petrograd Soviet responsible for the breakdown of discipline in the army. He also came to regard the Provisional Government as lacking the backbone to dissolve the Soviet and therefore unworthy of survival. On August 27, after several ambiguous exchanges with Kerenskii who desired to bring the Soviet to heel but not to eliminate the institution, Kornilov ordered General Krymov to lead the “Savage Division” and the Third Cavalry Corps on an assault of Petrograd.

Petrograd Soviet: Order to mobilize against the Kornilove Insurrection (1917) / From Through the Russian Revolution, by Albert Rhys Williams

This attempted putsch was an abysmal failure mainly because of the Soviet’s effective mobilization of workers and soldiers in defense of the revolution. The key defenders were armed workers organized into Red Guards, elements of the Petrograd Garrison, and railroad workers who halted the trains carrying Kornilov’s troops while they were en route to the capital. By August 31, Krymov was dead, having committed suicide, and Kornilov and several associates were under arrest. The main victor in the Kornilov Affair was the radical left, and in particular the Bolsheviks who had long warned of the danger of a counter-revolutionary thrust. Kerenskii’s authority and that of the Provisional Government were severely compromised, and the way now appeared open towards realizing Lenin’s injunction for the soviets to assume “all power.”

Bolsheviks Seize Power

Left: Military-Revolutionary Committee – Arrest of the Provisional Government (1917) / Hoover Political Poster Database

Right: The October Socialist Revolution / Hoover Political Poster Database

The Bolshevik seizure of power in Petrograd in October 1917 was celebrated for over seventy years by the Soviet government as a sacred act that laid the foundation for a new political order which would transform “backward” Russia (and after 1923 the Soviet Union) into an advanced socialist society. Officially known as the October Revolution (or simply “October”), it was regarded by the Bolsheviks’ enemies — and continued to be interpreted by many western historians — as a conspiratorial coup that deprived Russia of the opportunity to establish a democratic polity.

Left: Bolshevik regiments marching to Smolnyi (1917) / From Through the Russian Revolution, by Albert Rhys Williams

Right: Red Guards at the Winter Palace (1918) / From Through the Russian Revolution, by Albert Rhys Williams

“The Bolsheviks, having obtained a majority in the Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies in both capitals, can and must take state power into their own hands … The majority of the people are on our side.” Thus did Lenin, still in Finland as a fugitive from arrest on charges leveled in the aftermath of the July Days, cajole his party’s Central Committee in September. Lenin’s assessment of the shifting balance of forces was acute. So was his sense of urgency. The leftward swing in popular sentiment after the Kornilov Affair was strengthening the Bolsheviks, but also the more radical elements of the SR and Menshevik parties committed to the establishment of an all-socialist coalition government. While most Bolsheviks also favored such an arrangement and looked forward to the Second All-Russia Congress of Soviets as the vehicle for delivering it, Lenin was adamant that only an insurrection could deal a decisive blow to the Provisional Government and the threat of counter-revolution. On October 10, having returned to Petrograd, he obtained, by a vote of 10-2, a resolution of the Central Committee in favor of making an armed uprising the order of the day.

Left: The Petrograd Military Revolutionary Committee (1917) / From An Illustrated History of the Russian Revolution, by Valentin Astrov

Center: Fighting in the city (1918) / From Through the Russian Revolution, by Albert Rhys Williams

Right: The Armored Cars (1918) / From Through the Russian Revolution, by Albert Rhys Williams

It was a measure of the Provisional Government’s over-confidence and isolation that even after the two Bolshevik dissenters, Grigorii Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev, went public with their dissent, it did not take any decisive measures. In the meantime, the Bolsheviks managed to fashion the Military Revolutionary Committee (MRC) of the Petrograd Soviet into a command center for carrying out the insurrection. Kerenskii’s ill-conceived decision to shut down the Bolsheviks’ printing press, an action that evoked the specter of counter-revolution, turned out to be the impetus for the uprising. On October 24, Red Guards and soldiers under the MRC’s command, began to occupy key points in the city. By the following day, the assembled delegates to the soviet congress were informed that the Bolsheviks had taken power in the name of the soviets, and that they should proceed to form a Workers’ and Peasants’ Government. Within minutes, the battleship Aurora was bombarding (with blank shells) the Winter Palace, where most of the Provisional Government’s ministers waited in anxious expectation, and the Palace was stormed by Red Guards. As the Menshevik and SR delegates stormed out of the soviet congress in protest, Trotsky, the congress’ president, told them to join “the rubbish heap of history.”

First Bolshevik Decrees

Left: Fight for Socialism! (1918) / Hoover Political Posters Database

Center: Revenge on the Tsars! (1917) / Hoover Political Posters Database

Right: To Our Deceased Brothers in White Guard Trenches (1917-29) / Hoover Political Posters Database

In the early hours of October 26, 1917 the rump Second Congress of the Soviets adopted a proclamation drafted by Lenin which declared the Provisional Government overthrown and laid out the new soviet government’s program: an immediate armistice “on all fronts,” transfer of land to peasant committees, workers’ control over production, the convocation of the Constituent Assembly, bread to the cities, and the right of self-determination to all nations inhabiting Russia. That very evening the Congress met for a second time and took three actions: decrees on peace and land, and the formation of a new government.

Telephone switchboard (November 8, 1917) / Moscow: Krasnaia Gazeta, 1927

The decree on peace called on the belligerent powers to cease hostilities and commit themselves to no annexations or indemnities. It also appealed to the workers of Britain, France and Germany to support the Soviet’s decision, that is, in effect, to put pressure on their respective governments to enter into negotiations for a just peace. The land decree that Lenin composed took its brief from the SR program and the peasant “mandates” that had been delivered to the All-Russia Congress of Peasant Deputies in May. It proclaimed that “private ownership of land shall be abolished forever” so that land could “become the property of the whole people, and shall pass into the use of those who cultivate it.” By recognizing what already had occurred in many parts of the country, the decree legitimized the new government in the eyes of the peasants.

Left: Constitution of the Russian Socialist Federal Soviet Republic (1918) / Hoover Political Database

Right: Bolshevik sailors examining cars (1917) / From An Illustrated History of the Russian Revolution, by Valentin Astrov

Finally, the Congress approved the formation of the new governing body presented by Lenin, the Council of People’s Commissars (Sovnarkom). It consisted of all Bolsheviks, including Lenin as chairman and thus head of the government, Trotsky as commissar for foreign affairs, and Stalin as commissar for nationality affairs. The Congress also selected a new Central Executive Committee (TsIK), which was to exercise full authority in between congresses. Sixty-two of the 101 members of the TsIK were Bolsheviks, 29 were Left SRs, and the remaining ten were divided among Menshevik-Internationalists and other minor socialist groups. The exact relationship between Sovnarkom and the TsIK and the extent to which the rest of the country would recognize these decisions remained unclear for some time to come.

Constituent Assembly

Left: Viktor Deni – Constituent Assembly (1921) / Hoover Political Poster Database

Right: March for the Constituent Assembly! (1917) / Electronic Museum of Russian Posters

The convocation of a Constituent Assembly was one of the earliest and most popular demands to emerge from the February Revolution. As in the 1848 Revolution in France, when such a body, elected on the basis of universal male suffrage, had replaced the Provisional Government and drawn up a republican constitution, so in Russia it was an article of faith among both liberal and socialist parties that the revolution should take this course. Yet, deferring the resolution of fundamental issues until a Constituent Assembly could meet, the Provisional Government postponed elections until November 12 by which time it had been overthrown.

Kolchak: Supreme Leader of Russia (1918) / Hoover Political Poster Database

Despite his unwillingness to relinquish power, Lenin permitted the elections to proceed. This decision bought the Bolsheviks valuable time, as many who were opposed to their seizure of power considered the Bolshevik government as another in a series of temporary fixtures. In the elections the various factions of the SRs received approximately half of the 42 million votes cast, the Bolsheviks polled about ten million (24 percent) including roughly half of the soldiers’ vote, the Kadets received two million (five percent), and the remaining eight million votes went to other non-socialist parties, the Mensheviks, and parties representing national minorities. In a series of nineteen “theses” published in Pravda on December 13, Lenin made it quite clear that the Bolsheviks had no intention of being bound by the results of the election. First, he argued, the ballot was undemocratic because it had failed to distinguish between the Left SRs who had supported the October Revolution and other factions that had opposed it. Second, the republic of soviets then in the process of formation was a higher form of democracy than the Constituent Assembly because, he insisted, it represented the true interests of the working masses. Indeed, the decrees on peace and land as well as other measures adopted by the Soviet government made the Constituent Assembly less important in the eyes of many workers and soldiers.

All-Russian Jewish Congress (1917) / Hoover Political Poster Database

In the event, the approximately seven hundred delegates to the Constituent Assembly met for a single session on January 5, 1918 in the Tauride Palace. Having chosen the Right SR leader, Victor Chernov, as president of the assembly, the delegates approved the armistice with the Central Powers and issued a land law before being told to adjourn by the soldiers and Red Guards surrounding the building. The assembly planned to reconvene the next day, but was prevented from doing so by Red Guards on orders from the Central Executive Committee of the soviets. The Right SRs under Chernov eventually left the capital to set up a government of the Constituent Assembly on the Volga but, attracting little popular support, it was overthrown in November 1918 by the White general, Kolchak, who declared himself “Supreme Ruler.” Thus ended with a whimper Russia’s first exercise in parliamentary democracy, a casualty – like much else – of the October Revolution and the civil war.

Treaty of Brest Litovsk

Left: Leonid Pastenak – The Price of Blood on the Third Anniversary of the Imperial War (1918) / Hoover Political Poster Database

Right: Ioffe Kamenev at Brest Litovsk (1917) / From An Illustrated History of the Russian Revolution, by Valentin Astrov

The ruined fortress town of Brest Litovsk, deep behind German lines in occupied Poland, was selected by the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and Turkey) as the site to conduct negotiations with the new Soviet government. There, on December 2, 1917 an armistice was signed, but it would not be until March 3 (NS), 1918 that a formal treaty was issued. Even thereafter, military action continued for several months, as the German army pushed further and further into territories nominally under Soviet control.

H.R.E. – The Newest Film: Peace with Ukraine (1918) / Hoover Political Poster Database

Initially, the Soviet government’s strategy, as articulated by Trotsky, its commissar for foreign affairs, was “neither war nor peace.” That is, assuming that the capitalist world was on the brink of exhaustion and that Soviet defiance would rouse the oppressed masses of Europe to revolution, Trotsky argued (against the opposition of Lenin) that the negotiations should be used for propaganda purposes. However, after the Germans resumed military operations on February 18 (NS) and presented stiffer demands that included an end to the Soviet presence in Ukraine and the Baltic provinces, Lenin achieved a majority in the party’s Central Committee in favor of accepting the enemy’s terms. Thus, the Treaty of Brest Litovsk provided the fledgling Soviet government with a “breathing spell,” in effect buying it time by sacrificing space.

Ioffe Pokrovski: Trotsky at Brest Litovsk (1917) / From An Illustrated History of the Russian Revolution, by Valentin Astrov

This bow to expediency did not go down well with many Bolsheviks, not to speak of their sympathizers in Europe or Russia’s war-time allies who had feared just such a separate peace. At the Bolsheviks’ Seventh Congress, the treaty was denounced by Nikolai Bukharin and other so-called Left Communists as a capitulation to imperialism. It also was anathema to the Left SRs who, having supplied several commissars to Sovnarkom in December, withdrew them in protest and voted against the treaty at the Fourth Congress of Soviets. Their assassination of the German ambassador, Count Mirbach, in early July was preliminary to an uprising in Moscow, and the simultaneous but separately organized seizure of Yaroslavl’. In the meantime, the German army rolled across Ukraine, easily defeating the isolated soviet “republics” that had been established in Odessa, Kiev, and the Donets-Krivoi Rog, and installing General P. P. Skoropadskii as “Hetman” (Chieftain) of a thoroughly dependant Ukrainian state. The collapse of the German and Austrian-Hungarian empires in November 1918 left Ukraine once again up for grabs among the Ukrainian nationalist Rada, the Soviet Red Army, various peasant-based anarchist groups, and eventually. Poland. The German army would return in 1941.

Four Kinds of States

Communist Party Building

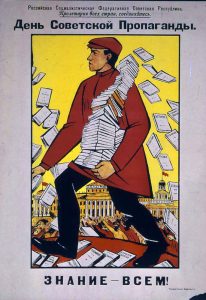

Comrade Workers! (1917-21) / Hoover Political Poster Database

The Communist Party (the Bolsheviks’ proper name after March 1918) styled itself as the “vanguard of the proletariat” and in this vein served as the nerve center of the new Soviet state. During its first years in power, the party metamorphosed into a hierarchically structured bureaucracy that functioned on the basis of discipline as mandated by the principle of “democratic centralism.” From 1917 through 1925, the party held annual congresses (as well as smaller and less formal conferences) at which delegates heard reports from leading figures, debated and voted on resolutions, and elected members to the Central Committee. The Central Committee stood at the apex of a hierarchy of committees that extended downward to the regions, provinces, and so forth, paralleling and shadowing the soviet administrative structure. The key personnel at every level consisted of secretaries whose appointment was based on “recommendations” from the next highest level up to the Secretariat of the Central Committee. This system also applied to other important assignments within the party and state and came to be known as the nomenklatura. As approved by the Eighth Congress in March 1919, the Central Committee created two other bodies: an Organizational Bureau (Orgbiuro) to manage the burgeoning party apparatus, and the Political Bureau (Politbiuro) to deal with “political questions” too urgent to await a full meeting of the Central Committee.

Join the Communist Party! (1920) / Electronic Museum of Russian Posters

The size of the party fluctuated a good deal during its first years in power. At the time of the October Revolution it numbered between 250- and 300,000. Many factors limited its growth thereafter including the elementary struggle for survival which left little time for active political engagement, political disenchantment especially in the spring of 1918, death at the front, and a purge (that is, removal) of passive members, deserters from the Red Army and other undesirable elements which was carried out in the spring of 1919. By August 1919 the Secretariat estimated total membership as no more than 150,000. As a result of intense recruitment, numbers increased to 430,000 by January 1920 and as many as 600,000 by March. But despite special efforts to recruit members from the working class, their proportion fell steadily throughout these years, from 57 percent at the beginning of 1918, to 48 percent in early 1919 and 44 percent a year later. The proportions of peasants, particularly lads who had served in the Red Army, and what the sources refer to as “employees,” that is, white-collar workers, correspondingly rose.

Stalin, Lenin, and Kalinin at the VIII Party Congress (1919) / Wikimedia Commons

The upper echelons of the party frequently were split over policy matters. Zinoviev’s and Kamenev’s opposition to armed insurrection in October 1917 provoked Lenin’s wrath, although they incurred no punishment. Oppositional positions soon emerged over other issues. The Brest Litovsk Treaty was opposed by the Left Communist faction which also voiced protest against Lenin’s willingness to rely on “bourgeois specialists” in industry and administration. Two former Left Communists, V. V. Osinskii and T. V. Sapronov, organized another opposition group, the Democratic Centralists, that lobbied for restoring autonomy to local party organizations and against the trend towards “appointmentism.” A Military Opposition emerged at the Eighth Congress against the professionalization of the army and the use of tsarist officers as “military specialists.” During the summer and autumn of 1920, unrest among industrial workers and the party’s rank and file crystallized in the form of a Workers’ Opposition. Led by Aleksandra Kollontai and Aleksandr Shliapnikov, it campaigned for trade-union control of industry. The party’s Tenth Congress passed a resolution denouncing the Workers’ Opposition as a “syndicalist and anarchist deviation.” Another resolution, “On Party Unity,” condemned both the Workers’ Opposition and the Democratic Centralists as fractional groups whose members risked expulsion from the party. These resolutions foreshadowed further tightening of restrictions on all forms of oppositional activity.

Economic Apparatus

Left: The Happy Worker in Sovdepia (1918) / Electronic Museum of Russian Posters

Right: The Rising Cost of Mens’ Woolen Suits in Sovdepia (1918) / Hoover Political Poster Database

Communism, as described by Karl Marx, resolves the inherent contradictions of capitalism. Private ownership disappears, as does social inequality and the exploitation of labor by capital. Lenin and his fellow Bolsheviks thought of communism only in the distant future, and during the long years of underground activity, their thoughts were focused on active resistance to tsarism. Only in the months leading up to the October Revolution did Lenin begin drafting ideas about the shape of a communist state. He distinguished the developed communism of the future, under which the state would wither away, from its earlier stages, in which a worker-run state would control the accumulation of capital. He predicted a long transitional period between capitalism and communism, demanding a strong role from the state.

Left: Iu. K. Korolev – How Was the People’s Money Spent Under the Tsars? (1918) / Hoover Political Poster Database

Right: Rising Cost of Shoes in Sovdepia (1919) / Hoover Political Poster Database

Though lagging behind Europe and North America, the Russian economy was still significantly modern. Its vigorous industries needed a modern infrastructure and legal system. Though untrained as economists, the Bolsheviks took charge quickly. As early as December 1, 1917, they established a Supreme Council of the National Economy (VSNKh) to organize a general economic plan and financial administration for the new state. Initially headed by V. Osinskii and from April 1918 by A. Rykov, VSNKh took its place in Sovnarkom as a kind of super commissariat with an elaborate infrastructure to handle its enormous but none too clearly defined responsibilities. VSNKh essentially presided over the nationalization, or confiscation of assets, of banking and industry and sought to work out a system according to which the most urgent tasks of production and exchange could be effectuated. It advocated seizure of all joint stock companies, annulled all loans made by the state before October 1917, and put labor unions in control of industrial enterprises. Through its branch units, known as main administrations (glavki) and regional economic councils (sovnarkhozy), VSNKh struggled mightily to gain control of and coordinate the economic resources of the country. Forceful though all these measures were, they contained more than a bit of wishful thinking, and betrayed an ambivalence about rapid or revolutionary approaches to economic reform. Along with his socialist utopianism and his revolutionary ruthlessness, Lenin had a practical streak that saw little use in destroying a vast economy. As a transitional measure, he advocated features of a large-scale capitalist economy such as individual managerial control, wage and piecework incentives, even the employment of bourgeois technical experts and managers.

Three Years of the Proletarian Revolution (1918) / Hoover Political Poster Database

The egalitarian (equalizing) impulse can be seen in the very first decrees of the Soviet state, which abolished the system of social estates and ranks that underpinned tsarist society. The decrees were followed eventually by an ambitious program of nationalization, based on the truism that property would be held communally under socialism. The program was not at all as predictable as it seems in retrospect. The first act of nationalization took place in December 1917, when all banks were merged into the State Bank that had been created by the old regime. This act was directed against currency speculation and the flight of capital, in the spirit of the slogan common in those days, to “Loot the looters.” Yet it involved no direct confiscation of funds, and was an amateurish takeover accomplished by revolutionaries with no experience in banking. Lenin and his comrades did not make confiscatory nationalization a state policy until six months into the Revolution. In spring 1918, the Sovnarkhoz issued instructions for the administration of nationalized industries, and begin to undermine the control of capital by private citizens by first nationalizing foreign trade, and then abolishing the principle of inheritance. By late summer and early autumn, the final foundations of socialist nationalization were put in place with decrees abolishing private real estate, private trade of all types, and nationalizing small industrial enterprises.

Building the Soviets

The Petrograd Soviet (1918) / From Through the Russian Revolution, by Albert Rhys Williams

The Soviet state, as conceived by Lenin and his closest comrades, was to be a state like no other, a “dictatorship of the proletariat” that would defend the workers’ and peasants’ republic and preside over the elimination of classes and, ultimately, of itself. But if, in Lenin’s words, soviet power was the “organizational form of the dictatorship,” what was the organizational form assumed by the soviets?

Every Cook Must Learn How to Govern the State (1925) / Electronic Museum of Russian Posters

An early indication of what was envisioned is contained in a Sovnarkom decree of December 24, 1917 which defined them as “organs of government” devoted to “the tasks of administration and service in all departments of local life.” Instructions issued by the Commissariat of Internal Affairs on January 9, 1918 elaborated on the tasks to be undertaken by the soviets. Finally, the Constitution (Fundamental Law) of the Russian Socialist Federated Soviet Republic, which was adopted by the Third All-Russian Congress of Soviets in July 1918, formally established the hierarchy of soviets beginning at the top with the All-Russian Congress, the Central Executive Committee (VTsIK) and Sovnarkom, and proceeding down to regional, provincial, county and rural soviet levels. This arrangement served as the model for the soviet republics of Ukraine and Belorussia upon their establishment in 1919 and others subsequently incorporated within the Union.

CED Presdium (1919) / From An Illustrated History of the Russian Revolution, by Valentin Astrov

But its tidiness on paper obscures a good deal of chaos, strong-arming, and improvisation on the ground. Even after the expulsion of Mensheviks and SRs from the VTsIK in July 1918, the delineation of functions between that body and Sovnarkom was quite blurred. This also was the case with respect to the commissariats, particularly at the provincial level where several typically claimed priority over the distribution of food and housing, the administration of industry, transport allocation, and educational policy. As far as elections to the soviets were concerned, many at the provincial and lower levels were annulled in 1918 after they had produced Menshevik and SR majorities. One trend that proved inexorable and irreversible was the shift in administration from the general meeting of soviet deputies to smaller executive committees (ispolkomy). This was in keeping with Lenin’s tirade in “The Immediate Tasks of the Soviet Government” (April 1918) against “petty-bourgeois disorganization,” if not his injunction to “weed out bureaucracy.”

Red Guard into Army

Left: Workers Defend Petrograd (1919) / Hoover Political Poster Database

Right: Chapaev (1918) / Russian State Film & Photo Archive at Krasnogorsk

Lenin and his closest comrades believed that one of the characteristic features of modern “bourgeois” states, a standing army, was undesirable and inappropriate for the Workers’ and Peasants’ Republic over which they presided. Thus, even as negotiations with the Central Powers were underway at Brest Litovsk, the old Imperial Russian Army was being dismantled. At the same time, however, it became apparent that the rag-tag Red Guard units and elements of the imperial army who had gone over the side of the Bolsheviks were quite inadequate to the task of defending the new government against external foes. Thus, on January 15, 1918 Sovnarkom decreed the formation of the Worker-Peasant Red Army, to consist of volunteers from among “the most class-conscious and organized elements of the toiling masses.”

Left: First Petrograd Red Army Soldiers (1918) / Moscow: Krasnia Gazeta

Right: Kalinin and Buddenyi at the Polish Front (1920) / Russian State Film & Photo Archive at Krasnogorsk

The architect of the Red Army’s formation was Trotsky who was appointed People’s Commissar for the Army and Navy in March 1918 and remained in that position until 1925. Assisted by General M.D. Bonch-Bruevich, a former Imperial Guard officer who served as head of the new Soviet Supreme Military Council, Trotsky assiduously recruited and defended the use of former tsarist officers, euphemistically known as “military specialists.” While few officers identified with Soviet power, many were willing to lend their services in the defense of Russia against foreign (initially German and Austro-Hungarian) forces. The introduction of politically reliable military commissars in April 1918 helped both to ensure the loyalty of the military commanders and to overcome resistance from rank-and-file soldiers to their commands. Abandoning the principle of a volunteer army, the Soviet government also introduced in April universal military training (Vsevobuch). Local call-ups and later in the year a general mobilization of conscripts aged 18-25 followed. Despite draft evasions and defections to the emerging White armies, the Red Army contained about 700,000 soldiers by the end of 1918. A year later its strength stood at nearly three million.

Left: First Petrograd Partisan Detachment (1918) / Moscow: Krasnia Gazeta

Right: Long Live the Three-Million Man Red Army! (1919) / From Persuasive Images: Posters of War and Revolution from the Hoover Institution Archives, by Peter Paret and Beth Irwin

During the civil war, the Red Army saw action on a wide variety of fronts, mostly in the south and east. Relying heavily on the Imperial Army’s arsenals of weapons and drawing on food supplies and horses from the interior, it vastly outnumbered its foes. The Red Army’s soldiers, overwhelmingly peasant in origin, received pay but more importantly, their families were guaranteed rations and assistance with farm work. This, plus literacy and political education classes, served to limit desertions and forge an esprit de corps that carried over into the years after the civil war. The army’s uniform, the long overcoat that overlapped at the front and the pointed cloth cap with red-star badge, were reminiscent of Muscovite-era warriors’ garb and proved to be among the civil war’s most enduring symbols.

State Security

Feliks Dzerzhinskii with Children (1950), by L. Krivitskii / Moscow Museum of Russian Impressionism

“Red terror cannot, in principle, be distinguished from armed insurrection,” wrote Trotsky in 1920 implying that the suppression of “counter-revolutionaries” grew inextricably from the Bolsheviks’ seizure of power in October 1917. The primary instrument of “Red terror” was the All-Russian Extraordinary Commission for Combating Counter-Revolution and Sabotage, commonly known as the Cheka after the initial letters of its abbreviated Russian title. It was established by a decree of Sovnarkom on December 7, 1917, effectively assuming the responsibilities that the Military Revolutionary Committee of the Petrograd Soviet had performed up to that point. The Cheka was the precursor of a succession of formidable Soviet secret police organizations that included the GPU (1922-23), the OGPU (1923-34), the NKVD (1934-43), the MGB (1943-54), and the KGB.

Volodarskii at His Wake (1918) / From An Illustrated History of the Russian Revolution, by Valentin Astrov

The Cheka was headed by Feliks Dzerzhinskii, a Polish Bolshevik who devoted himself unstintingly to building the organization. Initially comprised entirely of Bolsheviks, the Collegium of the Cheka was reorganized in early January 1918 to include several Left Socialist Revolutionaries who continued to serve even after the withdrawal of their fellow party members from Sovnarkom in March. Among them was Viacheslav Aleksandrovich, who was intimately involved in the brief Left SR uprising in July 1918 during which Dzerzhinskii was placed under arrest. Thereafter, Dzerzhinskii was loyally and ably assisted by Martyn Latsis and Iakov Peters (Latvians of farmer-laborer backgrounds), Jozef Unshlikht and Moisei Uritskii (both Jews), and the Russified Pole, Viacheslav Menzhinskii. All, with the exception of Uritskii, who fell to an assassin’s bullet in August 1918, and Menzhinskii, who succumbed to heart disease in 1934, were to be arrested and perish in Stalin’s purges of 1937-38.

With broad powers to investigate and nip in the bud counter-revolutionary plots, speculation and other serious crimes, the Cheka developed a justifiable reputation for ruthlessness. In September 1918, following Uritskii’s assassination and an attempt on Lenin’s life, Sovnarkom authorized the Cheka to step up its operations against counter-revolutionaries and class enemies. Reprisals were swift and extensive. In Petrograd alone, over five hundred executions were carried out. Official figures for 1918 of 6300 executions by the Cheka in twenty provinces are probably an understatement. Many thousands of others were incarcerated in political prisons and concentration camps. The “sword of the revolution” continued to be used unsparingly throughout and beyond the civil war. The disproportionate number of Jews and the presence of women in the Cheka fed anti-semitic and misogynist attitudes among the enemies of Bolshevism and the Soviet government.

Disintegration of the Old Society

Depopulation of the Cities

Peasant! You don’t have salt Peasant! / Hoover Political Poster Database

In the Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels characterized the development of society under capitalism in terms of the subjection of the countryside to the rule of the towns. “The bourgeoisie,” they wrote, “has created enormous cities, has greatly increased the urban population as compared with the rural, and has thus rescued a considerable part of the population from the idiocy of rural life.” On the eve of the First World War, approximately 20 percent of the Tsarist Empire’s population, or 28.4 million people, lived in what were officially designated as cities.

The largest cities were the two “capitals,” St. Petersburg and Moscow. The former contained two million people and the latter some 1.7 million. A second group of cities consisted of major commercial and industrial centers with large and multi-ethnic populations of between 500,000 and one million, e.g., Warsaw, Riga, Kiev, Kharkov, Odessa, Nizhnii-Novgorod, and Tiflis. A third category were provincial capitals such as Orel, Riazan’, and Tambov in the central agricultural region, Saratov and Simbirsk on the Volga, Tomsk in Siberia, Arkhangelsk in the Far North, Tashkent in Russian Turkestan, and Vladivostok on the Pacific. A fourth consisted of industrial cities that had sprung up or grew rapidly in population in the late nineteenth century such as Ivanovo-Voznesensk, a textile center; Yuzovka, a company town built in the Donets Basin around coal mines and a large steelworks; and Baku, the oil-producing city on the Caspian Sea. Finally, there were numerous smaller cities of heterogeneous character — county (uyezd) seats, river ports and railroad junctions, administrative outposts, etc.

Annihilate the Typhus-Bearing Louse! (1918) / From Through the Russian Revolution, by Albert Rhys Williams

The First World War profoundly affected urban life by uprooting civilians near the front and dispersing them among cities in the rear, diverting human and material resources to the army, and thereby creating shortages that fundamentally delegitimized the tsarist regime. Far from improving living conditions in the cities, the overthrow of the tsar in February 1917 further disrupted everyday life by intensifying inflation and shortages, complicating the imposition and maintenance of law and order, and encouraging citizens to seek even more drastic remedies for their woes. By October, food shortages (“tsar hunger”) had reached calamitous proportions. The persistence of workers’ ties to the village would save many of them when, during the desperate years of civil war, they fled from the starving cities. Others with no place to go were vulnerable to such epidemic diseases as typhus and cholera that swept through the cities thanks to the deterioration of urban infrastructure and their own physiological weakening.

Statistics on the industrial work force tell a story of diminution. From a high point of 3.5 million, the number of workers in ‘census’ industry (i.e., industrial enterprises employing more than sixteen workers) dropped to slightly over two million in 1918, and remained at between 1.3 and 1.5 for the remainder of the civil war. Losses were greatest in the most populous industrial centers, that is, Petrograd, Moscow, the Donbass, and the Urals. Petrograd’s population was halved within two years of the October Revolution, and the number of industrial workers in the city dropped from 406,000 in January 1917 to 123,000 by mid-1920. Between 1918 and 1920 Moscow experienced a net loss of about 690,000 people of whom 100,000 were classified as workers. Not until the mid-1920s did the urban population rebound to pre-war levels.

Food Supply

Left: Food Squad leaves for the countryside, Moscow (1918) / Russian State Archive of Film & Photo Documents at Krasnogorsk

Right: Bagmen at a railway station (1920) / Russian State Archive of Film & Photo Documents at Krasnogorsk

At the outset of the First World War, Russia’s officials judged its capacity to sustain the war effort in favorable terms, largely because of the country’s abundance of grain-growing regions. They could not have been more wrong in terms of their calculations. Within a year, shortages of articles of primary necessity — kerosene, footwear, textiles, and food — were registered in cities and towns throughout the empire. The foremost cause of these shortages was the diversion of resources, production and transport to war needs, which left inadequate supplies for the civilian economy. The creation of a Special Council for Food in 1915, the imposition of rationing, and other measures did little to alleviate the problem. Food riots, in which working-class women and soldiers’ wives figured prominently, were a frequent occurrence. The February Revolution was initiated in Petrograd by women workers’ protests over bread shortages. Food supply would continue to be a source of popular discontent throughout 1917 and beyond.

Left: Food Squad Commisar Stsemanovich (1918) / Russian State Archive of Film & Photo Documents at Krasnogorsk

Right: A Cry for Bread (1918) / From Through the Russian Revolution, by Albert Rhys Williams

The Provisional Government, having inherited the problem of food shortages, moved quickly to set up a State Committee on Food Supply (March 9) and establish a state grain monopoly with fixed prices (March 25). The monopoly was overseen by a hierarchy of provincial and district supply committees which, dominated by state officials, merchants, and landowners, attempted to impose requisition levels on the grain-producing peasantry. The entire process hinged on the assumptions that the currency in which peasants would be paid would remain stable, and that consumer goods would be available for purchase at equivalent prices. Neither of these assumptions was realized, and the result was frequent clashes between goods supply agents and peasants in the grain-surplus provinces and the exacerbation of food shortages in the cities. By late summer, Petrograd had only two days’ worth of bread reserves, a situation that jammed railroads, river ports, and roads with a new urban type, the “bagmen” – individuals acting on their own or as agents of various organizations who skirted restrictions on private sales of goods by traveling to surplus areas and carrying what they had purchased back to the towns and the grain-poor northern provinces.

Left: Line at a tobacco store (1918) / Russian State Archive of Film & Photo Documents at Krasnogorsk

Right: Members of the Food and Trade Control Commission (1918) / Russian State Archive of Film & Photo Documents at Krasnogorsk

By October, normally a month of food abundance, supplies had dwindled further, prices continued to rise rapidly, and lengthy food lines had become ubiquitous in the cities. The situation in Petrograd, far removed from the main food producing areas, was particularly grim. Only one-tenth of the prewar milk supply was reaching the city whose population had swollen owing to the influx of refugees and soldiers. Many desperate citizens resorted to shoplifting and ransacking of storehouses while others, outraged at being deprived of goods, set upon with fury those who were caught stealing or merely suspected of it. The problem of food supply thus delegitimized the Provisional Government, much as it had the tsarist government. The Soviet government continued many of the same food supply policies (e.g., rationing, state monopoly, requisitioning), albeit with a different ideological justification and greater ruthlessness, during the succeeding years of civil war.

Conflict with the Church

Left: Retribution (1918) / Hoover Political Poster Database

Right: Comrade Lenin Sweeps the World of the Unclean (1920) / Victoria Bonnell Russian Posters

Subject essay: James von Geldern The Russian Orthodox Church had a long history of collaboration with the tsars and hostility to the political left. The Bolsheviks, as atheist materialists, judged religion to be the ‘opium of the people’ of Marx’s famous formulation. Although they were relentless in their enmity toward religion, it is important to remember that the conflict between church and state began with the February Revolution, and arose when the church defended the unfair privileges it had enjoyed under the Romanovs. The conservative Orthodox hierarchy misread the tenor of the times. In June 1917, they demanded reinstatement of the primacy of Orthodoxy in the Russian state, ignoring the fact that Russia was a multinational secular state. Soon the church suffered two more serious blows. The first was the forced transfer of parochial schools to the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Education. The second was the Law on Freedom of Conscience. Together the legislation ended the official monopoly of the Orthodox church, and undermined its ability to force its faith upon the population.

Left: God Will Rise Again, and So Will Rus! (1918) / Hoover Political Poster Database

Right: Bolshevik Atrocities (1918) / Hoover Political Poster Database

One of the great ironies of history is the election of the Patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church, a dignity rescinded by Peter the Great, in the week leading up to the October Revolution. Though church liberals objected to the institution as non-democratic, the new Patriarch Tikhon was inaugurated on November 21, 1917. He immediately rallied resistance to the Bolsheviks when they continued the policies of the Provisional Government. Early acts passed by the Bolsheviks transferred church schools to the Commissariat of Education, and reaffirmed the freedom of conscience. Relations quickly grew bitter. On January 29, 1918, the People’s Commissariat of War declared all property of military church units subject to confiscation by non-church units, should the soldiers of the unit so desire. This minor act was perceived as an attack on all church property. Faced with legal state expropriations, impromptu seizures carried out in the name of the state, and seizures by peasants in the midst of rural turmoil, the church instructed parish clergy to resist expropriation by non-violent means. Measures included excommunication (hardly a threat to the Bolsheviks) and the use of the pulpit to condemn revolutionary laws. The Bolsheviks saw such sermons as ‘hostile propaganda,’ preached to an already wary peasantry.

Left: Anti-Bolshevik poster (1918) / From Glennys Young, University of Washington

Right: Archbishop Antonii Volynskii (1917) / Olga’s Gallery

The conflict escalated in February with the law separating church and state. Though similar to legislation debated under the Provisional Government, the Bolshevik law went much further. Education was fully secularized, and the church monopoly on civil ceremonies was abolished. Among the gravest measures was the nationalization of church property, and the denial of church rights to act as a juridical person. The assault was directed at the legal authority of the church, but it was directed also at the church monopoly on ceremonial life. The Bolsheviks adopted of the Gregorian calendar used by the western nations, replacing the outdated Julian calendar favored by the church. Church holidays no longer had state sanction, and the Bolsheviks began introducing a long list of their own revolutionary holidays, including May Day, Paris Commune Day (later revoked), and the anniversary of the Revolution (November 7, new style). Like the French revolutionaries they so admired, the Bolsheviks invented a new set of rituals for their holidays and ceremonies. It was clear that church-state relations were permanently abysmal by February, when the new Patriarch Tikhon pronounced an anathema on the Bolsheviks, not only condemning their souls to damnation, but forbidding the faithful from any concourse with them.

Death of the Old Culture

Left: Sten’ka Razin (1907) / From Vladimir Padunov, New Russian Media

Right: Moonlit Beauty (1916) / From Vladimir Padunov, New Russian Media

Marxism predicted that the culture of the old era would die with the dawning of a new era, but oh what a glorious death it was. The European war had cut Russia off from popular culture of the world, which allowed native production to boom, exploiting new technologies such as the cinema, gramophone recording, and mass printing techniques. Older forms such as music hall, variety stage (estrada in Russian), and popular literature experienced tremendous innovation. Popular culture became a big business, making millionaires of its entrepreneurs and celebrities of its stars. Although there was tremendous diversity of expression, mass culture avoided politics and the big ideas favored by the intelligentsia, which had dominated Russian culture in the nineteenth century. Mass culture found its great appeal while earning the contempt of intellectuals, a sentiment shared by Bolshevik leaders such as Lenin. Labeling mass culture entrepreneurs pornographers, either outright or because they eschewed big ideas, the new regime confiscated tools of production such as movie cameras and printing presses. Stars, who could get no jobs from the Bolsheviks, quickly ended up in emigration.

Left: Poison of the Big City (1917) / From Through the Russian Revolution, by Albert Rhys Williams

Right: Obliterating the Past (1918) / From Through the Russian Revolution, by Albert Rhys Williams

There was some injustice in the Bolshevik hatred of pre-revolutionary mass culture, which made a business of transgressing the social boundaries of class, gender and ethnicity, often by violating sexual taboos. Although Bolsheviks often seemed to regard sex, like religion, as an opiate for the masses, it was an effective vehicle for making social disparity visible. Popular literary genres included detective stories and robber tales, in which robbers and police alike could be heroes or villains. Pinkerton stories, featuring the American detective in a wholly Russian format, cast lower-class criminals in an evil light, and featured contempt for other nationalities; but the same readers could thrill to the exploits of “Light-fingered Sonka,” an Odessa Jew, who used her beauty and charm to penetrate the upper-class circles whose diamonds she pilfered. Sexual titillation could often reveal unspoken profiles of class, as when the Countess Actress of the famed Count Amori’s [Ippolit Rapgof] tale slept her way into the upper classes, encountering abusive husbands, ambiguous sexualities and aristocratic orgies along the way. Most famously the heroine of Anastasiia Verbitskaia’s Keys to Happiness went through a string of unhappy love affairs, discovering along the way something new to her non-fictional peers, that a woman can choose her own fate.

Left and Right: Portrait of Vera Kholodnaia, by Aleksandr Grinberg (1919) / Soiuz fotokhudozhnikov Rossii

These authors, as well as famous singers and actors, constituted an entirely new class of Russians, celebrities. Their faces featured in posters, magazines and newspapers, their love lives recounted breathlessly in the same, these stars emblazoned themselves in the consciousness of their compatriots. The fragile beauty of film star Vera Kholodnaia (Vera the Cold), the deep and storied eyes of actor Ivan Mozzhukhin, the dusky voice and beauty of Vera Panina, singer of the “gypsy” repertoire of melancholy love songs, and the cocaine-tinged piquancies of performer Aleksandr Vertinskii were often the first public mention of trends that would shape twentieth-century life. They coexisted with pious loyalty to the tsar, heartfelt patriotism, deep religiosity, and traditional domesticity in the complex Russian cultural environment; it was only the October Revolution that could not live with them.

Destruction of the Left

The Village “Blessed Virgin” (1919) / Brown University Digital Repository

When the Bolsheviks, having gained control of the Petrograd Soviet’s Military Revolutionary Committee, overthrew the Provisional Government, they did so in the name of soviet power. But quite a few of the 650-some-odd delegates to the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets that had convened in Petrograd opposed the seizure of power. They included Mensheviks, Right Socialist Revolutionaries (SRs), and the Jewish Bund who, in protest, walked out of the opening session of the Soviet Congress on October 25. The Left Socialist Revolutionaries remained in the Congress and some 29 were elected to the new Central Executive Committee (of a total of 101 members). However, the party decided not to participate in the Council of People’s Commissars and thus at its creation the new government consisted exclusively of Bolsheviks.

Anarchist bands in the woods (1918) / Wikimedia Commons

Almost immediately, efforts were undertaken by the Menshevik-Internationalists, Left SRs, and several members of the Bolsheviks’ Central Committee to reconstitute the new Soviet government as a broad coalition of Socialist Unity. This was explicitly rejected by the majority of the Bolsheviks’ Central Committee including Lenin. As a result, five members — Zinoviev, Kamenev, Rykov, Nogin, and Miliutin — resigned, claiming that they did not want “to bear responsibility for this fatal policy … which is carried out against the will of a large part of the proletariat and soldiers.” At the same time, five People’s Commissars, including Rykov, Nogin, and Miliutin resigned from their posts in protest. Lenin excoriated his erstwhile comrades as “deserters,” but soon agreed to accommodate the Left SRs. On December 12, three Left SRs took up positions in the Soviet government as People’s Commissars of Agriculture, Justice, and Post and Telegraph, only to resign as a protest against the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in March 1918. Left SRs continued to serve in the Cheka and other Soviet institutions until July when they organized the assassination of the German ambassador, Count Mirbach, and an abortive uprising against the Bolsheviks.

Elect the Socialist-Revolutionaries (1917) / Electronic Museum of Russian Posters

The Mensheviks and Right SRs splintered over the appropriate form of opposition to Bolshevik rule. Some joined forces with already-banned parties further to the right, such as the Kadets, in attempting to revive the Constituent Assembly after its dissolution in January 1918. Others continued working within the soviets, in fact achieving a number of victories in provincial elections during the spring, only to have the results annulled by higher soviet bodies. Attempts by members of these parties to organize strikes among workers usually were met with repression by the Cheka which also shut down the parties’ newspapers. The Cheka also dealt harshly with various anarchist groups in the capital. On June 14, 1918 the All-Russian Soviet Executive Committee resolved to expel all Right SRs and Mensheviks and to instruct local soviets to do likewise. Nevertheless, both parties continued to participate in the soviets, had a tenacious following in the trade unions, and sent delegates to all-Russian soviet congresses as late as 1920. Their end came in early 1921 when, without any formal decree, the Soviet government rounded up their leading figures and imprisoned or exiled them. Henceforward, the parties led a ghostly existence as convenient excuses for workers’ unrest and wavering within the ranks of the Bolsheviks themselves.

The Empire Falls

Left: To the Peoples of the Caucasus (1918) / Hoover Political Poster Database

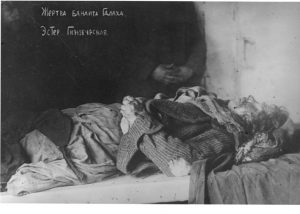

Right: Ester Ginzburg (1918) / Russian State Film & Photo Archive at Krasnogorsk

Nationalism, the identification of an “imagined community” based on nationality and the belief that it should be congruent with statehood, was largely confined in imperial Russia to small groups of urban-based intellectuals. The non-Russian peoples of the empire, consisting overwhelmingly of peasants, did not identify themselves so much in national terms but rather by religion, locality, or their peasant status. Nevertheless, the weakening of central authority after the overthrow of the tsar and the rapid deterioration of economic conditions created an opportunity for nationalist movements to assert claims for political leadership and the independence of “their” people. In the long run, which is to say beyond the years of revolution and civil war in Russia, those claims would be realized only in Finland, Poland, and the three Baltic states of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia. Elsewhere, political independence, achieved as a result of the implosion of Russian-based authority and in several instances with the sponsorship or support of another external power, was more short-lived.

Jewish Pogrom victims (1918) / Russian State Film & Photo Archive at Krasnogorsk

Among the earliest claims to national self-rule were those of the Ukrainian Central Council or Rada which was formed in early March 1917 and by April was led by the ardent nationalist and historian Mihail Hrushevsky. Demanding the right to form Ukrainian national regiments and tax the population, the Rada remained dissatisfied with the Provisional Government’s offer of compromise. Parties represented in the Rada received strong support in the Constituent Assembly elections of November, but the Soviet government’s refusal to concede independence on the Rada’s terms soon led to war. When the Rada proved incapable of stopping the Red Army’s advance in January 1918, it turned to the Germans whose price of support included requisitioning of grain from the peasantry. Peasant support for the Rada sharply declined, although the Bolsheviks, who also imposed requisitions, were no more to their liking. In the aftermath of the Brest Litovsk Treaty, the Germans dissolved the Rada and installed General Pavlo Skoropadskii as Hetman. His rule barely survived the Germans’ withdrawal in November 1918. Thereafter, Ukrainian territory was contested among the Red Army — aided by Russian or Russianized workers in Kharkov and the Donbass — various White armies, anti-Soviet Ukrainian nationalists under Semen Petliura, and roving bands of peasant anarchists under Nestor Makhno.

The Jew (1918) / Wikimedia Commons

The situation in other parts of the country where the population was predominantly non-Russian was no less volatile and confused after the overthrow of the tsar. In the absence of central authority, these borderland territories fell into the hands of local elites who in some cases spoke the language of socialism and in others legitimized themselves with reference to national or religious affinities. In Transcaucasia, soviets were established in the major cities of Tbilisi and Baku and enjoyed considerable popular legitimacy and local self-rule. With the October Revolution, the Transcaucasian socialist parties (excepting the Bolsheviks), declared independence for the whole region and eventually the three separate independent republics of Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. These republics survived only so long as the Red Army was preoccupied with combating the counter-revolutionary Whites. In Turkestan (Central Asia), indigenous pan-Turkic and Muslim renovationist movements battled Russian settlers (who themselves were divided between pro- and anti-Bolsheviks) for control of railroad lines, food supplies and other strategic resources. Elsewhere, in Tataria, Bashkiria, and Crimea, Turkic-Tatar movements vied with Reds and Whites for control. These and other parts of the vast Eurasian land mass remained essentially stateless until absorbed within the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic.

Creation of a New Society

New Letters and Dates

Left: Lenin Calendar (1922) / Hoover Political Poster Database

Right: Summer 1923 Calendar (1923) / Hoover Political Poster Database

On the morning of February 1, 1918, Soviet citizens awoke to discover that it was February 14. This was the result of a decision by Sovnarkom on January 24 that as of February 1 the Julian calendar which had been used in Russia to calculate days and months since the adoption of Christianity in the tenth century (but only since 1700 to calculate years), would be replaced by the Gregorian calendar. Because by the twentieth century dates according to the Julian calendar were thirteen days behind the Gregorian, February 1 became the fourteenth. Bringing the calendar of Soviet Russia into conformity with most countries of the world was a far less radical step than revolutionary France’s adoption of an entirely new republican calendar according to which 1792 was declared Year One and weeks lasted ten days.

Trostky Calendar / Hoover Political Poster Database

The use of the Julian calendar in Russia throughout the revolutionary year of 1917 explains why what was known as the February Revolution occurred, by the Gregorian calendar’s reckoning, in early March. Similarly, the April Days took place in early May, and, of course, the October Revolution happened in early November. As Trotsky noted in the preface to his History of the Russian Revolution, “The calendar itself, we see, is tinted by the events … Before overthrowing the Byzantine calendar, the revolution had to overthrow the institutions that clung to it.” The new government sought to instill the calendar change in the popular mind by creating a new calendar of holidays, including the Anniversary of the Revolution, May Day, Paris Commune Day, and others, on which the heroes and milestones of the revolutionary past were honored.

Left: May Day (1918) / Wikimedia Commons

Right: Autumn 1923 Calendar (1923) / Hoover Political Poster Database

Alphabet reform proceeded from a decree of the Commissariat of Enlightenment of December 23, 1917. This eliminated four letters from the Russian alphabet, reducing their number to 33. It was the first such reform since 1711. In the late 1930s, the Russian alphabet replaced the Latin (which had replaced Arabic during the 1920s) in Azerbaijan and Central Asia. It also served as the basis for alphabets used in Bulgaria, Yugoslavia and the Mongolian People’s Republic.

Culture and Revolution

Left: Red Wedge (1920) / Wikimedia Commons

Center: Monument to the Third International (1920) / From Bolshevik Visions: First Place of the Cultural Revolution in Soviet Russia, by William G. Rosenberg

Right: Our Train (1920) / From Building the Collective: Soviet Graphic Design, 1917-1937, by Leah Dickerman