Examining the circulation of ancient chemical knowledge.

Egypt

By Dr. Sydney H. Aufrère

Professor of Linguistics

Aix-Marseille University

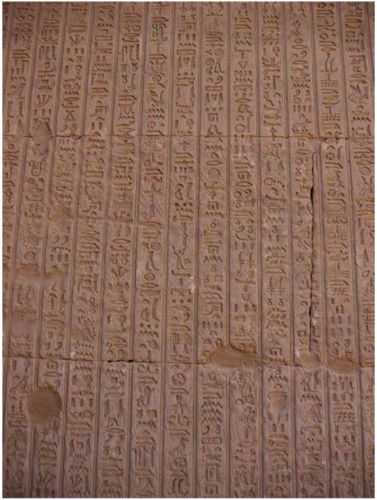

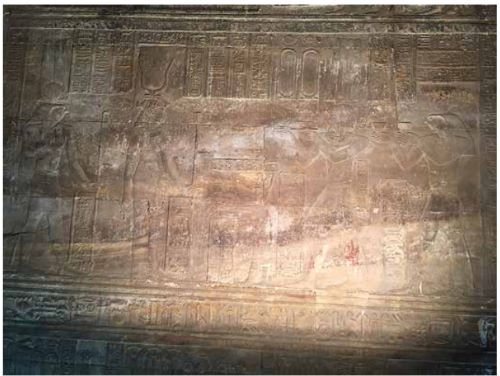

It appears that Egyptian craftsmanship had mastered specific procedures for the preparation of materials related to the sacred in order to always produce the same consistent product. However, unlike for Mesopotamia, Egypt left few traces of traditional recipes of liturgical perfumes requiring a long time to prepare (Bottero 2002; Plouvier 2010). Some recipes preserved on the walls of temples (Edfu, Athribis, Kom Ombo, Philae, and Dendara) give some details on the manufacturing processes used by the perfumers, the ingredients, and the order in which they were added. Inscriptions on the walls of Edfu’s so-called laboratory list the recipes for what was described as “finest ointment of styrax,” “the hekenu ointment,” “the medjes ointment,” “the nine ointments of the Ennead,” “the precious ointment,” “the ointment of divine mineral,” “the kyphi,” and the “pure natron pellets of the Ennead”; they also describe the different varieties of frankincense and styrax (Aufrère 1998c). Besides these recipes, other recently published medico-magical texts give details of some operations, thereby making it possible to reconstruct how the embalmer prepared mummies in the workshop.

The principles used in the preparation of Egyptian recipes were highly technical. The study of recipes engraved on the walls of Edfu’s laboratory shows that Egyptians used three types of preparations: fumigations, fat-based cooked ointments, and resinous ointments for the divine wood or stone statues to make them look like the representations that the Egyptians had of the gods. Indeed, as written in the “Memphite theology” (Twenty-Fifth Dynasty; Traunecker 2004), “This is how the gods entered their bodies, a mixture of all kinds of wood, of stone, of all types of faience, of all things which emerge from him and through which they manifest themselves.” What follows here describes how perfumes were generally manufactured, even if the preparations do not correspond exactly to what we would consider to be perfumes.

Some recipes such as that for the preparation of the “precious mineral ointment” were probably for local use. It is said that this ointment had once been used in Coptos to anoint the statues of Min-Amon. It contained a mixture of precious metals, minerals, bitumen, resins, and oils, products imported from foreign countries like Punt or God’s Land – in which the god Min, acting like a Bedouin, exploring the valleys of the Eastern Desert to the Red Sea in search of resources, was spreading his influence as “mineral prospector and collector of oleoresins.” Over time, this ointment had come to be used throughout Egypt to embellish the divine status of the gods’ statues (Aufrère 2005a: 242–6). However, the technical precision of these recipes, which described exactly how to follow them, made it possible to perpetuate the craftsmanship of perfumers. The modus operandi seemed to be always the same. The recipes first mentioned the name of the product and then specified the amount to be produced. This standard quantity was the hin, a unit of volume for liquids, namely 0.48 l. Why and for whom it was specifically prepared were then given. Then followed the chronology and the proportion of each ingredient to be progressively added. A recent study revealed the existence of seventy-one basic ingredients used in all these recipes (Aufrère 1998c: 60–2).

These operations were described with great precision. For example, the recipe for preparing a hin of hekenu ointment – principally made of premium frankincense oil mixed with styrax for divine anointing (Aufrère 2005a: 224–35) – required nine ingredients. Among these, there were two different qualities of frankincense and “the excellent wine of the Oasis.” The latter contained one key substance that appeared several times, namely alcohol. It indicated a specific process, since oleoresins are soluble only in alcohol. The perfume was obtained after successive and long operations. Some ingredients required individual processing, such as extracting the flesh of the fruit of the nedjem tree using a twisted cloth and then cooking it in a cauldron, not to mention the nature of the fuel used (the latter is changed during the preparation as the ingredients were added) for the processing. Other ingredients are added during the following operations, at specific times of the lunar calendar (e.g. the new moon). The cooking time required was specified. Before cooking, the mixture was weighed, and then regularly reweighed during cooking. If too much weight was lost, some liquid (water or wine) was to be added very gradually. The number of operations required to prepare this ointment – probably one of the most precise recipes of Edfu’s laboratory – amounted to around forty-two.

Time was therefore a fundamental parameter. The preparation of the hekenu ointment took between 487 and 492 days (Aufrère 2005a: 233), and that of the highest-grade extract of styrax required 303 days (Aufrère 2005a: 37). This extremely long preparation time gave the products greatly added value. As mentioned previously, the use had to be specified, because certain substances had to be used either fresh or dry. Chronologically, the material was first crushed then filtered through a sieve or a cloth to extract the vegetal debris, since perfumes were made with fresh or dry aromatics. Some preparations had to be kept warm during the procedure using a bain-marie. The vocabulary in perfume-making was always technical. It had nothing to do with the vocabulary used in religious or medical texts, which, from time to time, added a magico-religious formula when applying or absorbing a drug.

In general, the rule, even going back to the distant past, was to abide by the modus operandi of the preparation, presentation, and use that was declared in the Egyptian pharmacopoeia. Thus, the preparation of liturgical perfumes or recommended remedies always specified the ingredients, their quantities, how the medication was to be made, whether the ingredients had to be crushed or finely ground, how they were to be cooked, whether they were to be reduced, filtered, or not, and how they were to be administered. These products were sometimes used for fumigation.

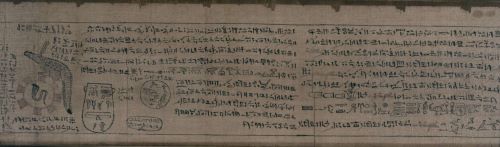

Traditional recipes were more or less precise. The recipe for the divine mineral ointment given in Edfu’s laboratory was purely technical, giving with precision the phases of preparation of the perfume. By contrast, the preparation of Papyrus Salt 825 evoked a fairly concise method of a similar perfume, ascribing an etiological legend to it and assigning a symbolic value to each component. Thus, the use of brief legends (historiolae) became associated with technical know-how. However, depending on the status of the text, the information was sometimes delivered only little by little. Thus, the ingredients to prepare inks – amalgams of metals, oleoresins (myrrh, frankincense), plant or mineral products, and animal by-products of magical or symbolic value (Aufrère 2001b) – were listed in the magical texts, but without explaining in what order they had to be added, triturated or not, and whether heating was required or not.

Two aspects should be highlighted here: the need to keep the tradition “alive” by copying the texts and the need not to disclose the secrets they contain to the uninitiated. The continual copying of the ancient texts ensured their preservation. The Ethiopian king Shabaka (716–702 BCE) of the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty ordered that a document written by elders and known as “Memphite Theology” be copied, as it was partially eaten by worms. The entire text was gradually reconstituted and engraved on a hard-stone support. This was considered a work of piety that allowed the sovereign to keep his name alive for eternity. It is important to note that there are several examples of texts copied despite gaps in the original. When a gap was observed, the scribe then wrote on the papyrus “gap found” (gem ush; i.e. text was missing) and continued copying. Elders, like the priest dresser (stolist) of Min at Panopolis (Akhmîm), Petarbeskhenis (Derchain 1987), a contemporary of Emperor Hadrian, encouraged young people to copy the ancient texts and to draw inspiration from them.

It was fundamental not to divulge the contents of sacred texts, because keeping them “secret” (Traunecker 1989: 108–10) gave added prestige to the liturgical or technical knowledge that was considered to be esoteric. The notion of “secret work” was frequently highlighted. According to the texts, it was important that knowledge be accessible only to authorized personnel, otherwise the processes involved would lose their mystery and hence their effectiveness. The engraving on the funeral stele of the artist Irtysen (contemporary with the Eleventh Dynasty, ca. 2160 BCE) reads that the mastery of his art be entrusted to his eldest son only, whom he considered as an initiate and therefore competent (Delamare 2007: 21; Stauder 2018a: 249). Secrecy veiled all complex preparations requiring a particular process. In the medical papyrus of the Louvre inv. no E 32847 is written the following recommendation: “No eye sees, no ear hears about (the composition of) your ointment, except that it protects the patient and the exorcist. The magic formula used by the embalmer priest who masters his art remains a well-kept secret” (Bardinet 2017: 223–4).

In yet other documents, instructions suggested that a magical compilation (Cairo, no. CGC 58027) dating from the Ptolemaic period meant to protect the royal chamber and relating to the composition of perfumes could not be seen by “any individual except by the king himself, the magician ritualist and perfumer in the House-of-Life” (Colin 2003: 95–6). One of the recipes kept in Edfu’s laboratory explicitly says the following about the divine recipe mineral ointment: “It is a secret that no one should see or hear, but which the old man passes on to his child” (Aufrère 2005a: 243). Moreover, the recipes of sacred perfumes reproduced in Edfu’s laboratory were supposed inaccessible to those who could not enter the sanctuary. As mentioned, the sacred library of Edfu cited a book entitled “List of all secret recipes of the laboratory” (Edfou III 348, 1; Aufrère 2005a: 218–19). The death penalty could be imposed on anyone who did not honor this secrecy. Thus, the Papyrus Salt 825 (XVIII 1) said: “Whoever would disclose this, he would die by murder, for it is a great mystery.” Nevertheless, some interdictions simply meant that some operations had to be done in private. “That this be neither seen nor watched,” said the author of Papyrus Louvre, inv. no. 32847 (VI, 19, 2–4), who added, “It is only if the coffin has neither been seen nor watched that it will be entirely decorated with a coating of gold and that the august deceased will be brought into it” (Bardinet 2017: 225). Indeed, the gold coating – the most sacred of all precious materials – on the coffin was an operation that had to be preserved from the impurity of having been seen by others. Hieroglyphic texts were not the only ones used to impose secrecy. The author of Ifao’s Coptic Medical Papyrus used an encrypted alphabet to write the names of products that the physician wanted to keep secret (Chassinat 1921). Although one may think there to be a distant connection, this encrypted alphabet had nothing to do with the sort of secrecy that permeated religious practices.

It is reasonable to think that the procedures to prepare these recipes, or at least some specific operations, were recited by a specialist. This was especially the case during the Ritual of Embalming (Goyon 1972: 26–7), a rite supposedly able to restore the vital functions of the dead. Whatever the nature of those products, including those intended for mummification, the texts were recited by a ritualist–magician. The texts of the Greek period referred to these specialists as “hierogrammats” or “pterophors.” Reading the texts aloud, the ritualist–magician provided a prompt for the practitioners, without participating in the technical operations reserved for specific personnel with pastophor status – that is to say, not constrained to the same degree of purity as the high-ranking priests. Reading the texts aloud specified the operating mode, added solemnity to the rituals, and supposedly changed the intrinsic quality of the results for which the products were made and the operations for which they were used. The written word prevailed on the experimental approach, as seen in the practice of medicine (Aufrère 2001c: 104–6).

However, reading the recipes of Edfu’s laboratory implies that their technical details had to be recalled by the perfumers preparing them, and the recipes acted like a sort of prompt or memory aid. It was undoubtedly the complexity of these preparations, their highly ritualized status, and the necessity of following with precision the conduct of operations in order to guarantee their efficacy that explains why the clergy insisted on keeping them in writing. The technical information discovered in these written texts prefigured the recipes of the alchemical papyri, in particular those of Leiden and Stockholm, which contained recipes for silver and gold, inks, stones, and dyes (Halleux 1981: 35–52). Concerning dyes and metallurgy, about which little is said in the texts in Edfu and Dendara, it is possible that texts of a similar nature may have been written and kept in the Houses of Life so named by the Egyptians, instigating the search for certified chemical processes – alchemy – to artificially create precious metals (gold or silver), whereas the Egyptians wanted to use only genuine precious metals intended to connote the divine.

It would seem that the memorization of sacred texts was greatly favored. In his Stromata (VI, 4, 35–8), Clement of Alexandria gave information showing that the high-ranking priests and pastophors (priestly personnel in charge of tasks that require a relationship with the public) of a temple not only were responsible for the maintenance of a number of books, but were also expected to “know them thoroughly,” to learn them by heart and memorize their contents. Thus, concerning the horoscope priest: “It is necessary that he has constantly present in memory the astrological treatises of the books of Hermes, four in number” (Stromata VI, 4, 35; Aufrère 2001c: 102–3).

The Egyptian perfumers also had access to information describing the products in terms of the qualities of oleoresins according to their origin, the season, and the way they were harvested. Although summarized on a product-by-product basis, such information, although not scientific, was significant because it avoided using products considered unsuitable for the gods. In the laboratories of the temples of Edfu and Athribis (Baum 1994a; Chermette and Goyon 1996; Baum 1999; Colin 2003; Aufrère 2005a: 253–9), there were two parallel lists describing the varieties of frankincense (ânty) and styrax (nenib). Recently a list for myrrh (khel) was identified in the temple of Athribis (Incordino 2016: 152–4). This type of presentation of information became a general model, which, by modifying what needed to be modified, described anything related to natural history in ancient Egypt. The diagram of these descriptions first specified the name, then the color, the aspect (viscous, soft, hard), the place where it came from, how it was presented (like tears, as a foam), the smell (pleasant or not), and other intrinsic qualities.

It should also be noted that the same model applied to products not used for liturgical rituals, pinpointing products of poor quality considered to represent the “eye of Seth.” Indeed, any reference to the “eye of Seth” indicated a secondary product and whether it was for medical use. It was quite possible that such a model had been applied to many other product lines to inform authorized personnel on how to use them, notably in the medical field. Although several of these lists, much more precise than the onomastica vocabulary, have disappeared, it is easy to postulate that they were necessary to know not only the pharmacopoeia but also the chemical substances they contained and their qualities.

This is what emerges, for example, from the examination of the fragments of the onomastica of Tebtunis, which provided information on the origins of exotic products that are difficult to recognize, such as “(country of) Heh: mountain of gold” and “(country of) Teferer: lapis lazuli mountain,” etc. (Osing 1998: 107). These examples are sufficient to demonstrate that specialists had at their disposal an extensive encyclopedic paratextual literature allowing them to stay close to the realities of the physical world and to be aware of the intrinsic qualities of the products they used in order to excel in their areas of expertise. Some of these products were potentially dangerous. Likewise, the venoms of snakebites were described and the chances of avoiding the toxic effects of some of them assessed (Sauneron 1989).

Specifically written for the use of specialist personnel at a given time, the sacred texts showed how important it was to ensure that they did not fall into oblivion. These texts could gradually become obsolete unless the changes made over time were explained. In summary, the technical vocabulary of a product or its know-how evolved over time, and what was understandable at one time was no longer so 100 years later. It was therefore necessary to explain these changes by making commentaries and glosses – sometimes comprising a sophisticated metatextual system – in order to update traditional knowledge and thus avoid misinterpretation by specialized practitioners.

One of the best-written texts, the Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus, included technical explanations of very high quality (Bardinet 1995: 493–517), implying the existence of similar metatextual literature in technical fields. Such glosses are also found in the recipes of liturgical perfumes. This is the case for kyphi, for which the author gives the names of equivalents having ancient names, the use of some of which had become obsolescent, replacing them with names that were easier to understand. Thus, the name of the plant “Ethiopian reed” was replaced by “feather of Nemty,” and that of the aromatic product “agaiu” (Aufrère 2005a: 250) by “mint.” We have already seen that the texts in the “Mansion-of-Gold” (Dendara) contained glosses giving equivalents to the traditional names of materials that were not immediately comprehensible to contemporaries.

In Roman times, when the meanings of the words attested to in the onomastica began to decay and the explanations given were no longer clear, a system of transliteration was developed using the Greek alphabet and letters formed by demotic signs (the so-called Old Coptic writing) to write in full the meaning that had been lost. These terms could also be transcribed into demotic (cursive writing, much used until the fourth century ce). These additions were presented as supralinear glosses, which allowed Egyptian scholars highly experienced in the elaboration of commentary – probably hierogrammats – to understand the textual follow-up word by word. The reading of technical texts was, theoretically speaking, facilitated by these glosses, which are interesting in many ways. They show, for example, on what model a large amount of technical knowledge, not to mention hermeticism, was gradually transmitted in Egyptian–Greek collaborative circles, bringing together those who boasted of being “philosophers,” literally “friends of knowledge” (Jasnow-Zauzich 2005: 13–5; Aufrère 2016a: 255–8).

Mesopotamia

By Dr. Cale Johnson

Professor of Ancient History

Freie Universität Berlin

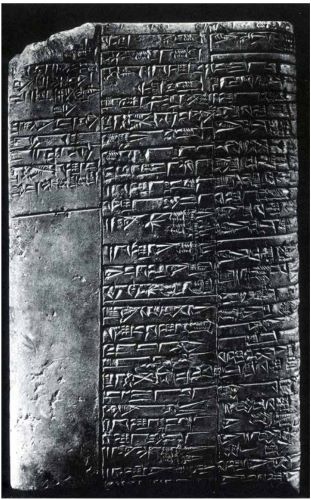

The transformation, transmission, and revaluing of procedures for manipulating objects and ingredients drawn from the natural world – often spoken of as recipes – is the most important domain for identifying and tracking scientific thought in the ancient world. In considering the role of recipes in Mesopotamia, however, we need to carefully distinguish between a sometimes unconsciously memorized sequence of actions and the textualization of a sequence of actions in written form. Many technical and medical/pharmaceutical procedures existed for centuries, if not millennia, before they were encoded in writing. Moreover, once standardized compendia of recipes emerge, in the Ur III and Old Babylonian periods (ca. 2112–1595 BCE), they often present us with only a few crucial elements of the procedure and little or no specific information on quantities of ingredients or details of procedure: the full recreation of any procedure often requires much additional information that is not present in the text. The medical/pharmaceutical recipes from Assurbanipal’s library at Nineveh (subsuming several physical locations on the citadel in the seventh century Bce; see Robson 2013) often use a placeholder such as “one shekel” for each ingredient, even when we know from other, non-library texts that much more specific quantities of each ingredient were known to specialists. We must assume that these schematic recipes, particularly when embedded in large, multitablet compendia, were not meant to be used in isolation. Students would, no doubt, have memorized large cross-sections of these materials as part of their textual and disciplinary training, but in the relatively few examples of recipe collections that were involved in practical contexts, we find much more specific quantities, means of administration, as well as comments on the effectiveness and seasonal appropriateness of specific remedies, global annotations, and qualifications that are almost never found in the library copies (the premier examples of this are in the medical school texts that Finkel published in 2000; see also Stadhouders and Johnson 2018).

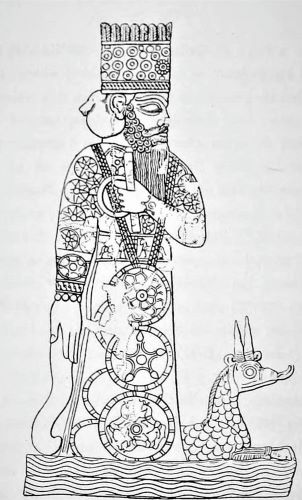

The Marduk-Ea formula is the best-known way of framing technical (including magical) knowledge in the cuneiform tradition (Falkenstein 1931; Cunningham 1997: 24–5, 115–21; Ceccarelli 2015). This literary pattern, in which two deities, father and son, prototypically Enki/Ea and Asalluhi/Marduk, discuss the illness of a human being, both authenticates the incantation-plus-ritual that Ea eventually hands over Marduk as “of the gods” and also sets out the role of the incantation-priest who will recite the incantation and lead the performance of the ritual. Just as Marduk witnesses the human being suffering from the disease and then travels to his father Ea, seeking a treatment, the human incantation-priest claims to act in the stead of the junior partner in the formula, namely Marduk. Later on, in the first millennium BCE, with the emergence of groups of physicians who were less interested in ghosts and demons as the cause of illness, we occasionally find medical compendia in which parodies of the Marduk-Ea formula appear, presumably an effort on the part of pharmaceutically oriented physicians to set themselves apart from the ghost- and demon-driven models of disease etiology favored by the incantation-priests (Johnson 2018). Even when groups of specialists disagreed about the proximate cause of illness or the most effective treatment, the formal properties of compendia in the legal tradition and the materials associated with the incantation-priest provided long-term models for the organization of sets of depersonalized case histories into technical handbooks and compendia (Johnson 2015).

The earliest recipes, often hidden away as unlabeled “ritual instructions” in collections of incantations in southern Mesopotamian traditions, are found in the Early Dynastic III period (ca. 2600–2400 BCE); the most recently published examples are several compendia tablets from the Schøyen Collection, published by George in 2016. The first of these tablets, MS 4549/1, includes both the earliest reference to Asalluhi (Sum. dasar) in the context of a Marduk-Ea formula, and also a small subset of incantations (vii 5–x 4) against stomach illness (Sum. ša3.gig), while the third of George’s tablets (MS 4550 obv ii′ 3′and following) likewise includes a section on stomach-related illnesses (ii), but no mention of Asalluhi. Several of these texts end with the patient drinking a specially prepared liquid (“water of Tigris and water of Euphrates” in MS 4549/1), presumably the final step in the production of these “drugs.” This family of incantations has been found in Abu Salabikh (IAS 549) and among the Sumerian incantations that were copied in Ebla in northwest Syria (VAT 12524 = Krebernik 1984, no. 11). More recently, a couple of Semitic-language texts written in Ebla, still from the end of the Early Dynastic III period (ca. 2400 BCE), present us with the earliest recipe collections, primarily TM.75.G.1623, in which individual drugs are paired with the illnesses they are meant to treat: “the name of the plant is ‘snake herb’: it is a treatment for swelling, bile, incontinence (?) and ‘hand of a god’” (Fronzaroli 1998: 227). Even here, where the focus is clearly on pharmaceutical remedies, only one or two steps are mentioned, and these steps are invariably part of the administration of the drug (“wrap it up and give it to the sick person to eat …”), rather than its formulation (Fronzaroli 1998: 228).

As recipes focusing specifically on medicine and other technical practices become more complex, and especially when scribes begin to gather them into multi-recipe collections in the Ur III and Old Babylonian periods, the obvious question was one of organization. In the Ur III period, when our earliest casuistically formulated legal compendia come into existence, such as the Codex Urnamma (Civil 2011), we also find our first evidence for medical prescriptions assembled into collections in a nearly unique Ur III tablet that Miguel Civil published in 1960: CBS 14221.

This collection includes no descriptions of symptoms or illnesses and consists solely of medical recipes, organized in terms of the means of introducing the drugs into the body of the patient: poultices and bandages on the obverse of the tablet, medicines to be drunk in the first half-column on the reverse, and in all likelihood suppositories for the last two columns. It is really here in CBS 14221 that we first see the type of step-by-step, second-person-oriented recipe that dominates the technical literature for the rest of cuneiform history. In lines 46–54, we get a typical example: “you should crush (Sum. u3.gaz) a.na.aš.du-plant, branches of camelthorn, seed from …, you should pour (Sum. u3.de2) it in beer, you anoint (Sum. i3.[bi2.še]š4) him (= the patient) with pure (or sesame) oil (and) you hang it (Sum. ab.la2.e) on him (as a poultice)” (Civil 1960: 60, prescription 1.4). Other than this large compendium (and one much smaller tablet), the evidence for procedural knowledge like this in the Ur III period is limited to the numerous tablets that list precise amounts of raw ingredients and finished products, as for example in the soup-, beer-, and perfume-making records, but do not directly list the steps in the production process (Stol 1990; Brunke and Sallaberger 2010; Brunke 2011). More detailed procedures are also implicit in a few Ur III texts, such as UIOM 892, the metal-alloying problem text, but in that case it is calculations of the different ingredients and the amount of waste products that drive the text, not step-by-step procedure.

The most important examples of step-by-step procedure emerge in the Old Babylonian period: these are well known in the realms of mathematics and cooking recipes, but there are also large compendia of medical prescriptions from this period that remain largely unpublished (Irving Finkel will publish, in future, a number of British Museum tablets that will greatly expand this corpus). In all three of these domains, second-person directives (“you do …” or “you should do …”), rather than imperatives, dominate the literary form of these materials, but first-person elements do occasionally appear as well. This contrast is most clearly seen in mathematical problem texts from the Old Babylonian period, where the problem is framed by someone in the first person, who can easily be assimilated to the role of the teacher, but the steps in the actual solution procedure are all in the second person, corresponding to the student (see, for example, the excavated pit problem in Høyrup 2002: 145, no. 23; Friberg 2007: 58–61). The Old Babylonian cooking recipes (YOS 11, 25–7) edited by Jean Bottéro in 1995, are almost entirely in the second person except for a short section in which first and second person alternate (YOS 11, 26 i 50–ii 20, already highlighted in Bottéro’s earlier 1987 paper):

I extract gizzard and giblets and after I have cleaned well (the pigeon), YOU place it to soak in water. I then cleave and I skin the gizzard, and after I bring water to boil, YOU place gizzard and giblets in a cauldron …

Bottéro 1987: 18, corresponding to Bottéro 1995: 74, 151–2; the English translation of these texts added at beginning of Bottéro 1995 renders all instructions, rather misleadingly, in the [second-person] imperative

This is not the carefully structured alternation between a teacher posing the problem in the first person and the student described as solving it in the second person that we see in mathematical texts, but in all likelihood, as Bottéro suggests, it is evidence for different types of textual traditions that were assembled into a single text by the editor. This type of variation between second- and first-person procedural instructions does not seem to occur in the medical texts. Crucially, in these Old Babylonian step-by-step procedures, the epistemological framing provided by the performatively and theologically complex picture of Marduk/Asalluhi and Ea/Enki is replaced with a bare-bones social scene in which an unnamed “teacher” addresses a similarly unnamed “student” in the second person.

The absence of any kind of authorization in these step-by-step procedures is something of a conundrum. None of these texts include historiolae or other incantations that might provide a link to a deity or other source of authority, nor does a Marduk-Ea-style frame appear in any of these texts. One might guess that the use of a properly casuistic formulation – “if … then …” – points to a broadly scientific milieu for these materials, but this type of formulation is regularly found only in the medical texts. The mathematic and culinary texts are more likely to start with a simple descriptive label like “an excavated room” or “gazelle broth,” but we should probably take the phraseological variety in YOS 11, 26, and 27 as the norm: alongside simple labels like “gazelle broth” and occasional uses of šumma “if” (preceding a hypothetical situation), we also find temporal phases using inūma “when” and purpose clauses consisting of the preposition ana plus an infinitive. These last two alternatives (“when …” and “[in order] to …”) occasionally appear in later medical compendia (and the purpose clause dominates in even later Aramaic materials), but temporal and purpose clauses are predominant in YOS 11, 26, and 27.

We have no direct social contexts for any of the mathematical and culinary step-by-step procedures in the Old Babylonian period (although Robson 2008 offers a broader social history of mathematics), but we do have, already in the Old Babylonian period, a parody known as At the Cleaners, in which a step-by-step procedure for laundering a garment is embedded in a dialogue between a fuller and his client (see Wasserman 2013 for a new edition and detailed study). The humor, in as far as we moderns can comprehend it, lies in the fact that the client adopts the first-person role of the teacher and addresses the actual expert (viz. the fuller) as if he were a student in the second person: “What I instruct you, do not lay aside, / Your own (ideas), you should not do! / As for the hem of the garment, you will lay down the selvage …” (Wasserman 2013: 274). But of course the deeper incongruity, which is only indirectly hinted at in a text like At the Cleaners, is that a written step-by-step procedure like this might lead a scribe or littérateur to the absurd conclusion that they could instruct someone about how to launder a garment by reading through a set of instructions. Indeed, the real goal – practical or literary – of step-by-step procedures like these is often unclear: any full-time specialist in cleaning clothes, cooking soup, or even formulating medical prescriptions probably had little use for these texts as an actual set of instructions. Like the mathematical texts, however, these procedural statements were almost certainly first produced as a kind of intellectual experiment: can we codify cooking in the same way the incantation-priests codify their ritual practices and incantations? Only once they had been textualized did other uses come to mind, whether defining the content of a discipline or, as in At the Cleaners, providing us with a parody of overweening scribal conceit.

It has long been recognized that the growth and elaboration of large-scale compendia largely took place at the very end of the Old Babylonian period or, more often, in the subsequent Middle Babylon period. As Rochberg puts it in her classic paper on “Canonicity in Cuneiform Texts”:

The process by which the celestial omen series Enūma Anu Enlil or any other omen series reached its final form is nowhere explained or even mentioned in our sources, but is likely to be the work of Kassite period transcribers and editors, since many representative texts of the scholarly tradition, omens, or lexical lists, emerged from the library of Tiglath-Pileser I (1115–1107 BC) in the form in which they are later attested in Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian copies.

Rochberg-Halton 1984: 127

In contrast to biblical notions of canonization, Rochberg argues for a much more limited and gradually evolving pattern of “text stability and fixed sequence of tablets within a series” (1984: 129). This process advanced at very different rates in different bodies of technical or scientific literature; major compendia that stood at the center of the work of the incantation-priest such as The Diagnostic Handbook and the incantation compendium known as Evil Demons (Utukkū Lemnūtu) were already being serialized at the end of the Old Babylonian period but only reached their received form in the early first millennium Bce (Geller 1985; Geller 2016: 3–26; as well as the catalogs and papers collected in Steinert 2018).

The latter phases of this type of editorial work, during the last centuries of the second millennium Bce, are epitomized by Esagil-kin-apli’s re-edition of The Diagnostic Handbook and The Physiognomic Corpus, a re-edition that is probably as close as Mesopotamia ever comes to an explicit model of editorial refashioning. Esagil-kin-apli was the chief royal scribe under Adad-apla-iddina (reigned 1068–1047 Bce), and from this august vantage (the most important institutional role for a scribe, after half a millennium of intense editorial work), he provides us with a unique statement of editorial method sandwiched in between the catalogs of Sakikkû (The Diagnostic Handbook) and Alamdimmû (The Physiognomic Corpus; see Heeßel 2000: 105; Schmidtchen 2018a: 147); he describes his source materials as “tangled threads … lacking an edition,” and goes about, in as far as possible, reordering the materials anatomically from head to foot (lines 51–2 in Schmidtchen 2018b: 316–17). These two lines are really a codicil attached to the total of forty tablets and 3,000+ entries rather than the formal statement of the editor, which starts in line 53 (the first line on the reverse of Ms B). But Esagil-kin-apli was not really speaking truthfully here; earlier editions of major components of his bipartite series certainly did exist. This is already evident from the subseries in The Diagnostic Handbook: the forty tablets of The Diagnostic Handbook are subdivided into six subsections, and subsections 4 and 5 largely consist of existing compendia that have been incorporated en masse into Esagil-kin-apli’s edition (Heeßel 2000: 107). More importantly, Heeßel published a tablet of materials from The Physiognomic Corpus (alamdimmû) in 2010 (viz. VAT 10493+) that describes one section as part of “the older (series) alamdimmû, which Esagil-kin-apli did not supplant,” suggesting that an earlier series of the same name existed in Assur and that the scholars in Assur refused to accept Esagil-kin-apli’s new edition (Heeßel 2010: 154).

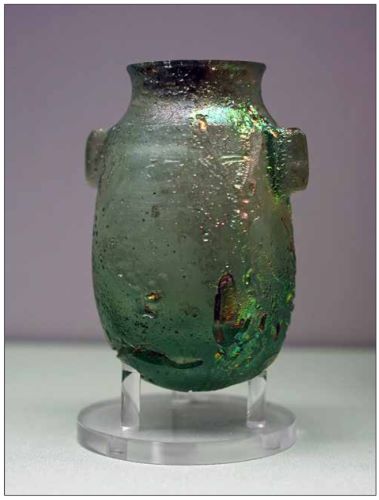

It was sometime in between the incipient serialization at the end of the Old Babylonian period and the competing compendia in the eleventh century BCE that the next wave of Akkadian step-by-step procedures were transmuted into textual form. The glass- and perfume-making texts, which have long been recognized as quintessential precursors for the history of chemistry, were first inscribed in clay at some point in this period, although the bulk of the glassmaking texts are only known from the first-millennium BCE copies recovered from the Library of Assurbanipal.

Thanks to a colophon in one of the perfume-making texts (KAR 220), we know that it was inscribed during the reign of Tukulti-Ninurta (1233–1196 Bce), while the earliest glassmaking text is a seemingly Middle Babylonian tablet (BM 120960) published by Gadd and Campbell Thompson in 1936. Like most scholarly texts from the second half of the second millennium BCE, there are few if any contemporary duplicates for these materials, and their interpretation is largely framed in terms of how they relate to later, first-millennium BCE materials from Assurbanipal’s Library or the Late Babylonian materials from Uruk.

All the more reason, therefore, to emphasize the cryptic orthography of the Middle Babylonian glassmaking text published by Gadd and Campbell Thompson. Martelli and Rumor, for example, have pointed out that linguistic-cum-orthographic puns in cryptic texts like this provide a crucial link between Mesopotamian sources and the recipes for dyeing metals associated with Pseudo-Democritus, especially a dyeing bath that includes “copper rust and bile of mongoose and vulture” (2014: 46). These are clearly Decknamen, and if we look carefully at the Akkadian term erû (meaning “eagle” but probably corresponding to “vulture” in Greek) in the Middle Babylonian glassmaking text, we can see the basis for its cryptic character. This raises the possibility that two different orthographies for erû “copper” were being used to differentiate the raw material (written with the usual logogram URUDA) and the label for the colored glass (TI8mušen, which normally means “eagle” but puns here on “copper,” both of which are erû in Akkadian). These orthographically distinguished homophones seem to underlie “(the bile of) the vulture” discussed by Martelli and Rumor. Be that as it may, Oppenheim was certainly wrong to claim that this, the earliest glassmaking text known, was not deeply encoded (Oppenheim 1966; Oppenheim 1970: 59–65; Martelli and Rumor 2014: 48 and n. 42).

The vast majority of the cuneiform glassmaking texts, just like any other group of texts in the first millennium BCE, are from the Library of Assurbanipal (reigned 668–627 BCE). Robson has emphasized that the “Library of Assurbanipal” is largely defined by its excavation in the nineteenth century (and role in present-day Assyriology):

It was dug by Austen Henry Layard and others in 1847–55, well before the advent of recorded, stratigraphic archaeology, yielding around 30,000 tablets and fragments. This first large discovery of cuneiform tablets made its way to the British Museum, where it is still housed today.

2013: 42

Although conceptualized by generations of Assyriologists as a single entity, Reade (1998–2001) shows that the tablets likely derive from a number of institutions and archives in eighth- and seventh-century BCE Nineveh, ranging from Sennacherib’s Southwest Palace or Assurbanipal’s North Palace to the temples of Nabu and Ishtar. It is, therefore, small wonder that nearly all glassmaking manuscripts stem from this massive yet somewhat artificially unified library.

The real surprise, however, is that the glassmaking recipes from Assurbanipal’s Library were already heirlooms in the seventh century BCE, presenting us with a battery of techniques more at home in the thirteenth or twelfth century BCE than the seventh century Bce. As Robson perceptively notes,

… glass-making technology had long-since moved on, with the introduction of casting and cold-cutting in about 900 B.C. … Around the same time, it became fashionable to add antimony to the glass mixture, making it an almost transparent shade of yellow or green in imitation of rock crystal … Why, then, were Neo-Assyrian royal scribes continuing to copy detailed instructions for an out-of-date technology?

2001: 51–2

Out-of-date and encapsulating at least two levels of glassmaking technology, the glassmaking texts are only known from library copies: they are not attested in personal archives or school contexts, and unlike the medical prescriptions, which were extracted, adapted, and specified in certain Late Babylonian contexts (see Finkel 2000: 140–1), the glassmaking recipes never appear in an applied or practical situation. There is slim but real evidence for a glassmaking compendium entitled “Door of the Kiln” (Oppenheim 1970: 25; Robson 2001: 53), but when we turn to later traditions, namely literary royal letters from the Late Babylonian and Seleucid periods, which seek to memorialize Assurbanipal’s tablet acquisition scheme (Beaulieu 2010), there is no specific mention of technical procedures like these (Frame and George 2005). The fact that glassmaking recipes do not appear elsewhere in the first-millennium BCE scholastic enterprise that compiled Middle Babylonian sources into Neo-Assyrian compilations – compilations that then often made their way to Seleucid-period Uruk in one form or another – suggests that they were never central to native intellectual histories in the first millennium BCE.

Greco-Roman World

By Dr. Matteo Martelli

Professor of History of Science and Technology

Università di Bologna

Small workshops in classical Athens were run by lone craftsmen whereas larger businesses employed slaves, if the owners could afford to buy them as fellow-workers (Acton 2014: 272–74). In both cases, in the archaic and classical periods, both textual and archaeological sources show that crafts such as weaving, pottery, and simple metalworking were taught in family workshops, being transmitted from father to son and, in some cases, to extended kin (Hasaki 2013). The apprenticeship could last for several years, depending on the complexity of the craft being learned: almost ten years, for instance, were necessary to properly master pottery production, from the first steps (e.g. collecting and preparing the clay) to the most advanced skills, such as learning how to use wheels and kilns as well as how to decorate the produced vases (Hasaki 2013: 193). In the case of sizable enterprises employing gangs of slaves – such as the knife factory that Demosthenes inherited from his father (Or. XXVII 9) – skilled slaves, even without being freed, could sometimes manage the activities of the workshops on behalf of their wealthy owners. Freed slaves – whose names have been recorded, for instance, in the fourth-century Bce Attic “Manumission bowls (phialai),” which mention wool-workers, goldsmiths, gem-cutters, and blacksmiths (Jordan 2000: 99) – could also set up their own businesses and continue practicing the professions they learned in the workshops of their former masters (Acton 2014: 281–8). From a speech of the classical orator Hyperides (fourth century BCE), we know that Athenogenes, an Athenian citizen of Egyptian origin with two generations of perfume-sellers behind him (Hyp. III 19), owned three perfumery workshops in the city, one of which was run by the slave Midas and his two sons. The extraordinary price of thirty minae for which they were sold (the average cost for a slave was of three to four minae) might be justified by their exceptional skills, which it is likely they developed after a long apprenticeship (Acton 2014: 243).

Learning a craft would not only take a long time, but it could also be exhausting and painful. In a letter inscribed on a lead tablet found in the Athenian Agora (inv. no. IL 1702, fourth century Bce), Lesis, an apprentice in a workshop for metalworking (chalkeion), describes to his family the severe punishments he suffered there: he was afraid he would die, being always whipped, tied up, and treated like dirt by his wicked masters (Jordan 2000; Hasaki 2013: 185–6). A similar scene seems to have been represented in a fifth-century BCE skyphos (wine cup) found at Abai in Lokris (National Museum, Athens, inv. 442), where a pottery workshop is depicted: above a painter sitting at the wheel we see an apprentice who

… has been suspended face down from the ceiling. His left foot is tied against the ceiling itself; his right foot hangs lower, from a cord … Another cord from the ceiling is around his neck, strangling him so badly that his tongue hangs out.

Jordan 2000: 100

Lesis asked his family to come to his masters and find something better for him.

The apprentice–master relationships were regulated by agreements, which, according to later papyri, could imply two possible conditions: apprentices either worked in the workshops by day and spent the night in their homes or they lived with their master until the end of the training period (Jordan 2000: 99). Almost forty apprenticeship contracts (didaskalikai) have been discovered in papyri from Greco-Roman Egypt; even though they mainly deal with the textile industry (especially weaving), other professions are also recorded, such as nail-making, coppersmithing, or building (Bergamasco 1995). Petosirirs, for instance, sent his son to the master Herakleides, a coppersmith (chalkotypos), submitting, at the same time, an application to register his son in the lists of the quarter where Herakleides’ workshop was located (PSI VIII 871, first century CE). In Greco-Roman Egypt, in fact, apprentices were registered in groups officially recognized by local authorities, who could tax them. Craftsmen had to pay regular taxes (cheironaxion) on the trade produced by their workshops, which could benefit from the work that young apprentices were doing while learning the art. In some cases, however, craftsmen committed to teaching their art could apply for tax reductions in return for the service they provided to the city (Freu 2011: 28).

As regulated by apprenticeship contracts, masters were expected to provide their apprentices with clothing and food as well as to pay them wages, which could be adjusted to the different phases of the training; more advanced students contributed more effectively to the output of a workshop, and they were to be paid accordingly. In return, students were obliged to obey their masters and work full time in their workshop (in some cases, holidays were stipulated in the contracts), while fines were imposed if they decided to quit abruptly. The length of the training period could vary significantly, from six months to several years, depending both on the complexity of the art being learned and on the range of skills the students wished to acquire. Among the students, papyri mention both sons of craftsmen and slaves. In the latter case, patrons invested in their slaves, who were sent to a master and, after learning an art, could set up a lucrative business for their owners. On the other hand, craftsmen could also decide to send their own sons to the workshops of other artisans in the same trade, so that the sons could extend their set of mastered skills beyond a family tradition. Moreover, similar apprenticeships could also strengthen the links between different families, professionals, and masters of various workshops. As recently pointed out by Liu (2017: 219), “both apprenticing one’s son to a fellow practitioner, and the acceptance of that child from a fellow practitioner as an apprentice, can be interpreted as tokens of trust, especially since they involved sharing trade secrets as well as information about clients, credit, and supplier networks” (see also Freu 2016).

Artisans often associated themselves in professional corporations or guilds – the collegia in Latin. Papyri from Greco-Roman Egypt often mention groups of various craftsmen working in the same field, which could include only a few members (Van Minnen 1987: 48–72). Latin inscriptions, on the other hand, testify to the status of Roman corporations that, in some cases, could remain active for various decades, such as the collegium fabrum tignariorum (builders and carpenters) and the collegium aromatariorum (pharmacists) in Rome (Liu 2017: 206–12, with further bibliography). Guilds both served the economic interests of their members (collective payment of taxes, mutual support in case of financial difficulties) and promoted civic, social, and religious activities. A papyrus from Tebnytis (P.Tebt. II 287, second century ce), for instance, preserves the official record of an appeal that fullers and dyers of the Arsinoite nome (district) made against what they held to be an undue amount for the tax upon their respective trades. The guild of silversmiths in Ephesus gathered in the theater of the city when their interests, mainly linked to the making of small silver shrines of Artemis, were threatened by some Christian followers of Paul, who denied the sacred nature of these objects. To their choral chant in the theater of “Great is Artemis of the Ephesians,” the city’s grammateus responded by reassuring them that the city, as a guardian of the temple of Artemis and her images, would protect their trade (Acts 19: 24–40; see Venticinque 2016: 167–9). In the mid-fourth century CE, four inscriptions from the Egyptian temple of Deir el-Bahari testify to the regular sacrifices of donkeys that a guild of ironworkers from Hermonthis offered to the Egyptian demigods Amenhotep and Imhotep (Łajtar 1991).

Less clear is the role played by corporations in apprenticeships; some scholars have supposed that they could have acted as intermediaries between students and masters (Van Minnen 1987: 69–71; Freu 2011: 28–9). Fullers and dyers are mentioned together in a list (probably a tax list) given in a papyrus from Tebnytis (P. Carlsberg 53; second century CE). The bottom of the papyrus deserves particular attention: after mentioning a dyer called Tyrannos Kroniōnos, the list goes on (ll. 12–3) to give the name of “Orsenouphis, son of Heron, supervisor (hēgoumenos, “leader”) of the weavers in Tebtynis, for the screening of apprentices.” As already pointed out by Van Minnen (1987: 70–1), Orsenouphis was probably leading a guild of weavers that was somehow involved with the training of new apprentices (Freu 2011: 35).

The apprenticeships of dyers probably followed similar rules and took place either in the workshops of external masters or in family workshops, where the art of dyeing was passed on from father to son (Wipszycka 1965: 146). Justinian’s Digest XXXII 91,2 (from the jurist Papinian) mentions a workshop (taberna purpuraria) willed from father to son, while in a sixth-century CE papyrus (CPRX 124, ll. 4–6) two dyers (bapheis), father and son, are mentioned. On the contrary, no ancient source seems to mention supervisors for the screening of apprentices with reference to a guild of dyers.

The inscription Alt. v. Hierapolis 227 (third century CE) must be mentioned at this point, since the text records a certain M. Aurelius Diodorus Corescus who left an amount of 3,000 denarii to the guild of purple dyers (perhaps his colleagues), whose leader was required to burn poppies on his tomb every year. But if they neglected to do so, the money had instead to go to the ergasia thremmatikē, a term that has been interpreted by some scholars as a collegium alumnorum or an association of slaves’ children. This hypothesis, however, was severely criticized by Van Minnen (1987: 71, n. 142).

In the alchemical literature from Greco-Roman Egypt, the motif of the transmission from father to son was inherited and reshaped in various narratives about the original revelation of the alchemical art. In the first century CE, (Pseudo-)Democritus is said to have received his initiation into the dyeing arts – which included, as already pointed out, the making of gold, silver, and precious stones, along with purple dyeing – from the Persian master Ostanes in the Egyptian temple of Memphis: even though Egyptian priests and other apprentices were taught by the master, Ostanes kept his books hidden only for his son (Martelli 2013: 82–5). Likewise, the angel who revealed the secrets of gold- and silver-making to Isis made the goddess swear to pass these instructions only to her son, Horus (CAAG II 33–4). In a more historical context, Zosimos of Panopolis addressed most of his alchemical teaching to the wealthy woman Theosebeia, who is sometimes introduced as the “sister” (adelphē) of the alchemist (Souda Z 168; Hallum 2008). The term probably refers to an alchemical kinship, stressing the tight relationship between teacher and pupil, as one can infer from Zosimos’ complaints when Theosebeia temporarily joined another group of alchemists led by his rival, the Egyptian priest Neilos (CAAG II 190).

All these examples introduce a second crucial element in the alchemical apprenticeship: alchemy was, first of all, a craft that was to be learned from books. According to Zosimos’ account of the Enochian myth, a book entitled Chēmeu – from which the term chēmeia (i.e. “alchemy”) derived – was the main secret revealed by the fallen angels (Martelli 2014a). Zosimos himself often urges his pupil Theosebeia to study the books of the ancients, which represented the basis for any alchemical training; their reading always supported the personal teaching of the master, who was expected to guide his pupils through the technical instructions left by the founders of the discipline.

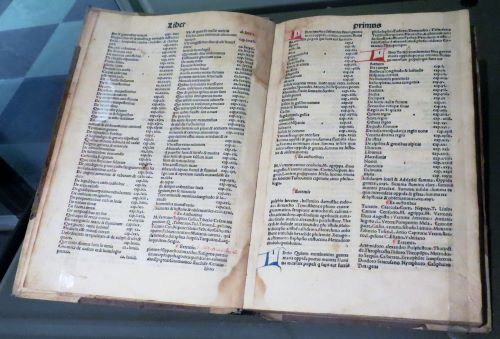

The books of the ancients – such as Pseudo-Democritus’ alchemical writings, to which Zosimos always refers – certainly contained recipes, which may be identified with the smallest units of any alchemical text (Halleux 1979: 74). Collections of recipes, on the other hand, started circulating in Greece centuries before the first appearance of alchemical books. Medical recipes, for instance, are included in various writings of the Hippocratic corpus, either in sections devoted to specific diseases (e.g. Diseases I and II; Internal Affections) or in catalogs, such as in Diseases of Women I and II. Probably based on earlier small collections selected and reorganized by the Hippocratic authors, these recipes omit crucial information (e.g. instruments to be used in preparing the drugs and quantities of single ingredients). They have therefore been interpreted as “short aide-mémoires, which needed to be supplemented through oral explanations; these recipes could not, and did not intend to, replace the oral word” (Totelin 2009: 258).

A few decades later, the philosopher Theophrastus included various recipes for the making of perfumes in the second part of his treatise On Odors. These recipes seem to derive from direct contact with the experts working in Athenian workshops. Theophrastus himself was the son of a fuller, and firsthand experience in his father’s workshop may explain the analogies he drew between wool-working and perfume-making (On Odors, 17). Indeed, Theophrastus’ account is based on direct observation of workshop procedures and an ongoing exchange with perfumers, whose different opinions on the preparations of perfumes are reported by the philosopher. However, the author did not mean to write a handbook for perfume-makers (Reger 2005: 257–9).

More technical, on the other hand, are the recipes for perfume-making collected in the treatise De materia medica by the first-century CE physician Dioscorides, one of the heirs of the rich and sophisticated pharmacological tradition developed by Hellenistic physicians. This tradition represented the basis for Galen’s writings on the composition of drugs. Galen claims to possess the best selection of recipes in the Roman Empire, which contained expensive formulas assembled from all over the world (On Avoiding Distress, 31–7). In his De materia medica, Dioscorides included the recipe of the precious Egyptian incense called kyphi (Diosc. I 25), which is also recorded both in hieroglyphic inscriptions (e.g. in the temples of Edfu and Philae) and by Plutarch, at the end of his treatise On Isis and Osiris (383e). In this work, after listing all the ingredients of the perfume, Plutarch specifies that they were not mixed at random, but according to the sacred writings that were read to the perfumers as they were mixing the ingredients. Therefore, “sacred writings” (hiera grammata), to be identified with written formulas for kyphi, seem to have been used in ancient workshops, perhaps read aloud by a master to his fellow workers. The use of books in a workshop is apparently confirmed by a famous fresco in the House of the Vettii in Pompeii, which depicts various cupids performing the different steps necessary for the preparation of a perfume. In the middle of the fresco, a scene displays a papyrus scroll (perhaps a recipe book) next to a little flask into which a cupid pours the perfume.

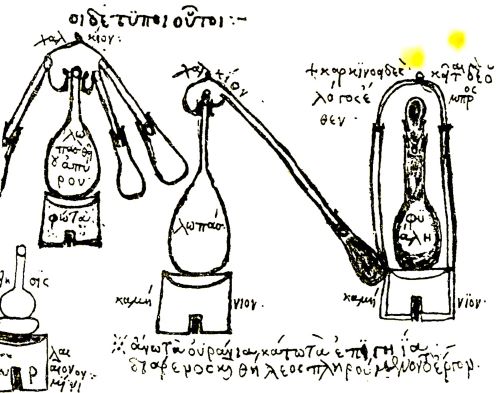

A similar use in workshops has been proposed for the two alchemical recipe books preserved in the Leiden and Stockholm papyri. As already seen, the two papyri collect more than 200 recipes on a variety of dyeing and metallurgical techniques, along with instructions on how to produce artificial gemstones and make golden and silver inks. Written in a codex format, they might have allowed potential users who looked for specific recipes to browse through the collection more easily than in a papyrus scroll. Although the lack of stains or signs of damage (which, presumably, would have been left by their use in a workshop) has led scholars to consider the papyri mainly as copies for libraries (Halleux 1981: 27), one cannot rule out that they were simply read aloud by a master in his workshop (like in the case of the kyphi formulas) or were based on earlier workshop copies (Clarke 2013: 13–8).

Bjoertvedt, Wikimedia CommonsThe wide range of techniques considered by the compiler(s) of the two papyri, however, implies a broad umbrella of competencies, which were scattered among different categories of experts, such as metallurgists, makers of fake precious stones, glassmakers, or dyers (Martelli 2011: 280–1). As discussed above, each of these craftsmen developed a high degree of specialization through long and demanding apprenticeships, so that specialized craftsmen in antiquity probably never committed themselves to learning and practicing such a variety of technai (“arts”). Obviously, we cannot exclude the possibility that more specific recipe books devoted to single arts were circulating among specialized craftsmen. For instance, P.Iand. 85 (Halleux 1981: 158–60; first to second centuries CE) preserves recipes focused on purple dyeing only, while Pliny the Elder (NH XXXVII 197) informs us of commentarii devoted to the making of precious stones. In recipe 53 of the Stockholm papyrus (Halleux 1981: 125), we find an interesting reference to unspecified writings (presumably on the making of precious stones):

Corroding and opening up of stones. Grind alum and melt it carefully in vinegar. Put the stones therein, boil it up, and leave them over night. Rinse them off, however, on the following day and color them as you wish by use of the recipes (graphai, lit. “writings,” perhaps recipe-books) for coloring.

transl. by Caley 1927: 987

The Leiden and Stockholm papyri, in fact, preserve a few references to their sources. In the Leiden papyrus, recipe 89 reads (Halleux 1981: 105): “How to fix Alkanet. Urine of sheep, or komaris, or henbane as in the recipe 55.” Perhaps we find here a reference to recipe 147 of the Stockholm papyrus, which gives the same instructions for fixing alkanet. If we only consider the section on purple dyeing of the Stockholm papyrus (recipes 89–159), recipe 147 is no. 58 of this section, a position that is very close to the numbering given in the reference that we find in the Leiden papyrus. Perhaps a smaller recipe book on purple dyeing was among the sources used by the compiler of the two papyri (Halleux 1981: 105, n. 3). Indeed, recipes were organized around specific areas of expertise in the four books of Pseudo-Democritus, and these short procedural texts continued to be the major vehicles for the transmission of alchemy in the following centuries. In late antique and early Byzantine recipe books we find various references to the tools of craftsmen, such as the furnaces of glassmakers (CAAG II 307–8) and goldsmiths (CAAGII 305), along with their crucibles (the Leiden papyrus, § 68 in Halleux 1981: 100). If the identification between these artisans and ancient alchemists is problematic (Halleux 1981: 28; Martelli 2011: 280–5), a certain overlapping between their areas of expertise – maybe implying direct contacts and mutual exchanges – seems to emerge from the available sources.

Conclusions

By Dr. Marco Beretta

Professor of History of Science and Technology

Università di Bologna

The art of making recipe books containing instructions on how to make perfumes, glass, and other chemical products seemed to have originated in Egypt and Mesopotamia and it was successfully embodied in the Greco-Roman technical literature and was equally successfully transmitted to early modern times. If we consider the completely different material means by which literary texts were composed in these three civilizations, the continuity of this tradition is all the more remarkable. Although Egyptian civilization left few traces of chemical recipes, the surviving ones preserved on the walls of temples contained extremely detailed technical operations and, unlike medical texts, were mostly devoid of any religious references. The record of chemical recipes was important to ensure the transmission of knowledge to future generations but, at the same time, it was crucial to keep this knowledge under the control of a restricted circle of people (priests and scribes). The tension between public record on the one hand and secrecy on the other was destined to accompany chemical recipes until the end of the seventeenth century.

In Mesopotamia, compendia of recipes did not contain all the technical know-how displayed in the artifacts produced in the laboratory, thus showing a gap between the practical knowledge preserved in the workshop and its literary record. A feature that was destined to play a crucial role in the composition of recipes was the use of the second person in procedural instructions.

Greco-Roman artisans specialized in guilds and transmitted their knowledge within a more standardized set of rules, both legislative and literary. In the alchemical literature of the Greco-Roman period, the Egyptian and Mesopotamian traditions were enhanced within a theoretical framework that tended to give a higher status to chemical arts. Many recipes recorded in hieroglyphic inscriptions ended up in recipe books such as the Leiden and Stockholm papyri and thus provide an extremely interesting testimony of the circulation of chemical knowledge.

See bibliography at source.

Chapter 7 (187-210) from A Cultural History of Chemistry in Antiquity, edited by Marco Beretta (Bloomsbury Academic, 05.19.2022), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.