By the time British troops felled the Liberty Tree in 1775, the movement it had nourished had already outgrown it. The ideas first acted out in the streets of Boston had migrated into pamphlets, congresses, and declarations.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

In March 1765, the British Parliament enacted the Stamp Act, a measure requiring colonists to pay duties on all printed materials, from newspapers and legal documents to playing cards.1 This direct tax represented Parliament’s first attempt to raise revenue from the colonies without their consent, sparking immediate outrage. In Boston, where economic hardship and class tensions already simmered, the act struck a particularly volatile nerve. The resistance that followed would transform the city into the epicenter of colonial defiance.

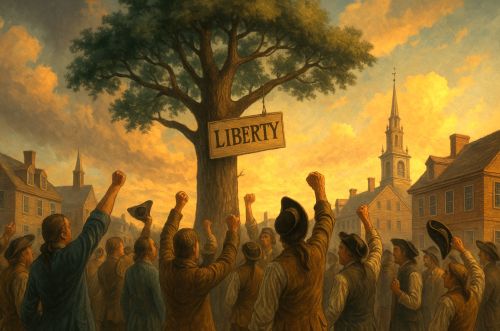

Among the earliest organizers of that resistance was a secretive group of middle-class merchants and artisans known as the Loyal Nine.2 Recognizing the need for public force behind their political aims, they recruited Ebenezer Mackintosh, a shoemaker and leader of the South End gang, to mobilize Boston’s working-class crowds.3 On August 14, 1765, the result of this alliance erupted into one of the most dramatic protests in colonial history. An effigy of Andrew Oliver, the appointed stamp distributor, was hung from a large elm near Boston Common, soon to be christened the Liberty Tree, before being paraded through the streets and burned. That night, the mob destroyed parts of Oliver’s property, compelling him to resign the next day.4

The event marked a turning point. It proved that coordinated intimidation could render royal authority powerless in the colonies’ most rebellious city. It also introduced the Liberty Tree as a powerful symbol of resistance, rallying point, and political myth. The Loyal Nine and Mackintosh’s men, working from opposite ends of Boston’s social order, had shown that popular protest could fuse elite coordination with street power. In doing so, they laid the groundwork for what would soon emerge as the Sons of Liberty, a movement that linked civic ideology with raw public energy, transforming riot into revolutionary purpose.

Context: Boston in 1765

By 1765, Boston was a city of contradictions. Its economy was recovering unevenly from the postwar downturn that followed the Seven Years’ War, and its social fabric was strained by widening gaps between merchants, artisans, and laborers. The port bustled with trade, but imperial regulation and postwar debt pressed hard on its people. For working-class Bostonians, particularly the apprentices and laborers of the South End, Parliament’s new tax confirmed what they already suspected, that Britain’s distant legislators treated colonial subjects as a revenue source rather than partners in empire.5 The rhetoric of “no taxation without representation,” though coined by elite pamphleteers, resonated viscerally among men who had little property yet bore the brunt of inflation and unemployment.

Politically, Boston stood apart from other colonial towns. It combined a strong tradition of local self-government with a volatile culture of crowd politics that had deep roots in English urban protest.6 Street demonstrations were not new; “Pope Night” processions, where rival gangs paraded effigies through the streets in anti-Catholic revelry, had long offered young men like Ebenezer Mackintosh a stage for theatrical rebellion.7 These customs normalized collective violence as a civic ritual, a fact that colonial elites both feared and, at times, exploited.

The Loyal Nine emerged from this charged environment as a bridge between social classes. Comprised largely of printers, craftsmen, and small merchants, including figures later absorbed into the Sons of Liberty, the group recognized that effective resistance required more than petitions and pamphlets.8 They needed the credibility and muscle of the streets. Mackintosh, already known as a charismatic organizer of the South End gang, supplied both. His followers had honed their skills in symbolic spectacles and knew how to seize public attention without descending into chaos. The Loyal Nine’s partnership with Mackintosh thus reflected a pragmatic alliance: respectable leadership cloaked behind the energy of the crowd.

That alliance carried significant risk. By harnessing popular anger, the city’s elites flirted with the forces they sought to contain.9 Yet the social composition of Boston made such collaboration almost inevitable. In a city of roughly sixteen thousand people, most living within a compact peninsula, communication between taverns, workshops, and meeting houses was constant. Rumor traveled fast, and outrage faster still. When news of the Stamp Act spread through the wharves and alleyways, Boston’s social geography ensured that resistance would not remain confined to the pages of protest pamphlets; it would take to the streets.

Mackintosh, the South End Gang, and Mobilization

Ebenezer Mackintosh was not the sort of man colonial elites typically entrusted with political missions. A shoemaker by trade, born into Boston’s working class, he earned local notoriety as “captain” of the South End gang, a rough but disciplined group that dominated the annual Pope Night festivities.10 In these raucous celebrations, rival gangs from the South and North Ends competed to display the largest, most elaborate effigies of the pope, complete with bonfires and mock battles. Though seemingly carnivalesque, these events functioned as political theater, allowing the disenfranchised to voice anger through ritualized defiance.11 Mackintosh’s mastery of these performances made him an ideal conduit for channeling popular unrest into organized action.

The Loyal Nine understood this. Most were artisans or tradesmen themselves, but they lacked the manpower and street credibility necessary to translate elite discontent into public protest. They turned to Mackintosh not merely as an agitator but as a tactician.12 His ability to mobilize hundreds of working men with little notice proved crucial. Through informal tavern networks and word-of-mouth communication, Mackintosh could convene large crowds capable of transforming protest into spectacle. His leadership on August 14, 1765, was no accident; it was the culmination of years of communal practice in orchestrated dissent.

The partnership between the Loyal Nine and Mackintosh also exposed the deep symbiosis between Boston’s social strata. While the Loyal Nine planned the symbolic framework of resistance (the effigy, the procession, the location) Mackintosh’s men executed it.13 They ensured that the demonstration projected both menace and discipline: the crowd was loud but purposeful, destructive yet politically precise. In their fusion of planning and passion lay the essence of early American protest politics. The leaders supplied ideology; the crowd supplied energy. Each depended on the other.

This alliance, however, was fraught with tension. The very crowds that made elite protest effective also frightened the colonial gentry who endorsed them. As historian Gary Nash observed, “the middle and upper classes learned to use the mob as a blunt instrument, one that could not always be recalled once unleashed.”14

Mackintosh’s independence and popularity soon alarmed the city’s leaders, who feared he might become more radical than the cause required. The uneasy dance between social respectability and mass mobilization, first seen in 1765, foreshadowed the political balancing act that would characterize Boston’s revolutionary decade.

The August 14, 1765 Action

The protest of August 14, 1765 began at dawn, when townspeople discovered an effigy of Andrew Oliver hanging from a towering elm on the edge of Boston Common.15 The effigy, crudely fashioned but instantly recognizable, bore symbols of greed and royal corruption, a stamp glued to the forehead, a devil at its feet, and a boot representing Lord Bute, the minister blamed for the tax. Crowds soon gathered, swelling throughout the morning until the event assumed the scale of a public festival. It was not spontaneous: the staging bore clear signs of coordination between the Loyal Nine and Ebenezer Mackintosh’s men, who kept order even as they provoked outrage.16

By afternoon, the demonstration had evolved into a choreographed act of defiance. The effigy was cut down and carried through the streets in a noisy procession past the Town House and down King Street, each stop chosen to dramatize colonial subjection.17 When the crowd reached Oliver’s office, they symbolically decapitated the effigy before burning it on Fort Hill. What followed blurred the line between protest and riot. That night, hundreds marched to Oliver’s Dock Square home, tore down fences, broke windows, and destroyed much of his property. The violence, though alarming to Boston’s elite, achieved its intended result: by morning, Oliver publicly resigned his commission as stamp distributor.18

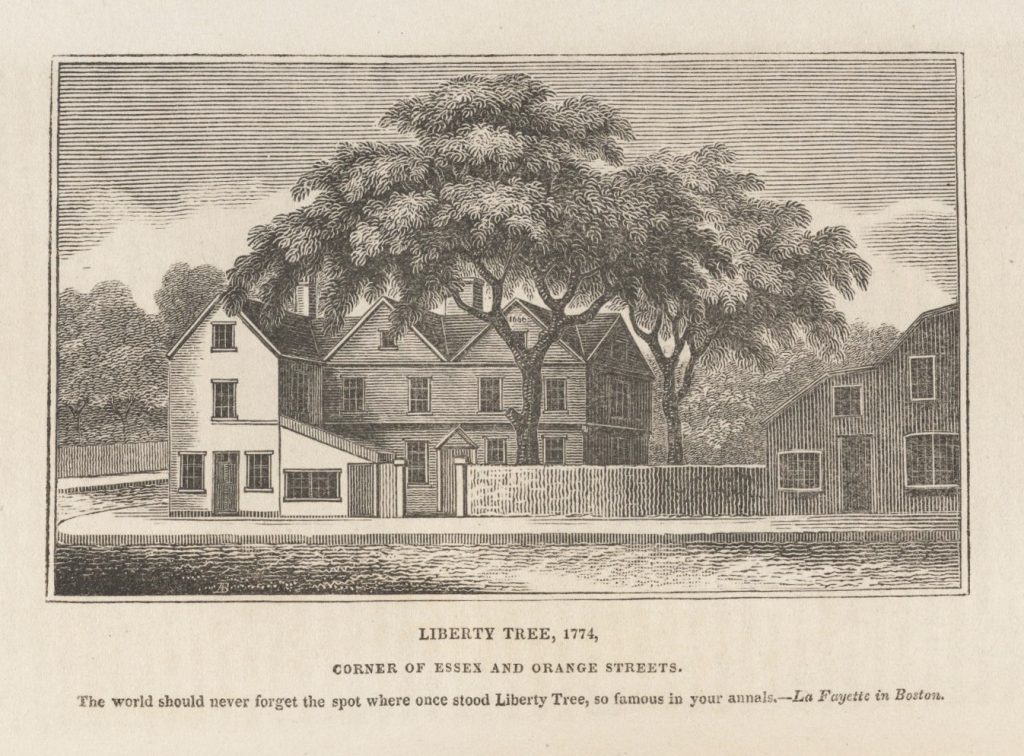

The day’s events struck like a shockwave through the colonies. News of Oliver’s humiliation raced along the Atlantic seaboard, emboldening protests in Newport, New York, and Charleston.19 In Boston itself, the protest reshaped political geography. The elm where the effigy had hung was declared the “Liberty Tree,” and gatherings there soon became ritualized: sermons, meetings, and announcements all radiating from its shade.20 The coordination between the Loyal Nine and Mackintosh’s crowd showed that political legitimacy could arise not from Parliament but from the people assembled in common cause. The act of hanging an effigy thus acquired deeper resonance: it inverted the power of the gallows, transforming a symbol of royal punishment into one of popular judgment.

Yet the aftermath also revealed the fragility of this new unity. While radical printers celebrated the “people’s triumph,” Boston’s selectmen condemned the destruction of private property.21 The Loyal Nine, eager to maintain respectability, began to distance themselves from Mackintosh’s gang. For the moment, though, their joint action had demonstrated something unprecedented, that coordinated intimidation could render British authority impotent. No one in Boston would attempt to enforce the Stamp Act again. The colonies’ most turbulent city had effectively nullified a parliamentary law through organized defiance, and the world had taken notice.

The Liberty Tree, Symbolism, and Legacy

In the wake of the August 14 riot, the elm tree that had borne Oliver’s effigy became the beating heart of Boston’s resistance. Crowds gathered beneath its branches for meetings, speeches, and readings of Parliament’s latest decrees.22 It was there that the first true “Sons of Liberty” assembled, transforming spontaneous protest into ritualized opposition. The Liberty Tree was not merely a landmark; it was a stage for civic identity. In a world without mass media, its physical presence gave abstract ideals (liberty, consent, and popular sovereignty) visible form.

The symbolism spread rapidly. Within weeks, towns from Portsmouth to Charleston designated their own liberty trees or poles, each imitating the Boston model.23 What had begun as a local act of defiance became a continental network of symbols, linking colonial grievances into a shared narrative of resistance. The repetition of the ritual (gathering, speech, effigy) functioned as a kind of political liturgy, one that sanctified rebellion as patriotic duty. The British saw only disorder; the colonists saw awakening.

For Boston’s radicals, the Liberty Tree also offered something subtler: a space that blurred class boundaries.24 Artisans, merchants, apprentices, and gentlemen stood side by side, momentarily united beneath its canopy. This mingling of ranks defied the rigid social hierarchy of eighteenth-century urban life. In that equality of presence lay the seed of republicanism, the notion that virtue and voice were not limited to the well-born. The Loyal Nine had used the crowd for expedience, but the crowd, gathered under the Tree, began to imagine itself as the source of legitimacy.

The British authorities recognized the danger. By 1767, Governor Francis Bernard was already denouncing the gatherings as seditious “mobs,” and the Liberty Tree as a “rendezvous for the disaffected.”25 His fears were well-founded. Each meeting under the elm eroded the aura of imperial control and elevated Boston’s radical leadership as representatives of the “people.” When the tree was finally cut down by British soldiers in 1775, the act only confirmed its power; it became a martyr to the very cause it had inspired.

The Tree’s symbolism endured long after its trunk was gone. Revolutionary orators invoked it in sermons and pamphlets; engravers depicted it as the cradle of American liberty.26 Its image migrated into the broader vocabulary of independence, appearing on flags, coins, and tavern signs. The ritualized defiance that began beneath its branches evolved into the political theater of the Continental Congress and, later, the culture of public demonstration that defined the new republic. The crowd politics of 1765 had become a constitutional habit.

Yet the legacy was not purely heroic. Some contemporaries worried that popular mobilization could as easily devolve into anarchy as produce liberty.27 The uneasy alliance between elites and the crowd never fully resolved; it merely evolved into new forms of political negotiation. Still, the Liberty Tree remained the Revolution’s most potent symbol of unity and defiance, a living metaphor for the idea that sovereignty could grow from the ground up. In Boston’s August 1765 protest, Americans first learned that liberty could be rooted, tended, and defended not by decree, but by the people themselves.

Conclusion

The uprising of August 14, 1765, was far more than an outburst of mob anger. It represented the first coordinated fusion of elite strategy and popular energy in the American colonies, a collaboration that transformed protest into a prototype of revolution.28 The Loyal Nine provided the ideological framework and moral justification; Ebenezer Mackintosh and his South End followers supplied the emotional power and physical presence. Together they forged a model of public resistance that would define Boston’s political culture for the next decade.

In the short term, their actions rendered the Stamp Act unenforceable. Andrew Oliver’s resignation set off a domino effect across the colonies as other stamp agents, fearing similar reprisals, withdrew.29 Parliament had the law, but Boston had the crowd and the crowd proved stronger. The event exposed the practical limits of imperial authority when confronted by collective colonial action. For the first time, British officials faced a population that could not merely petition but compel.

The deeper legacy lay in symbolism. The Liberty Tree stood as both monument and metaphor, a living emblem of the idea that freedom required public vigilance.30 Gathering beneath its branches, colonists rehearsed the language and ritual of republicanism long before independence was declared. The Boston protest transformed abstract grievances into visible drama, teaching Americans how to perform liberty before they possessed it.

At the same time, the uneasy alliance between elites and the populace foreshadowed the tensions of the Revolution itself.31 When power shifted to “the people,” questions of control, class, and violence followed. Mackintosh’s story reminds us that the Revolution’s origins were neither tidy nor purely philosophical; they were loud, crowded, and combustible. Yet from that disorder emerged a coherent political faith: that ordinary citizens could claim authority by collective will.

By the time British troops felled the Liberty Tree in 1775, the movement it had nourished had already outgrown it.32 The ideas first acted out in the streets of Boston had migrated into pamphlets, congresses, and declarations. The effigy that once hung from an elm had become a new image altogether: a people defining their own sovereignty. In the August 1765 revolt, Americans discovered that liberty was not granted; it was made, defended, and remembered.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Edmund S. Morgan and Helen M. Morgan, The Stamp Act Crisis: Prologue to Revolution (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1953), 18–22.

- T. H. Breen, American Insurgents, American Patriots: The Revolution of the People (New York: Hill and Wang, 2010), 67.

- Alfred F. Young, The Shoemaker and the Tea Party: Memory and the American Revolution (Boston: Beacon Press, 1999), 24–28.

- Pauline Maier, From Resistance to Revolution: Colonial Radicals and the Development of American Opposition to Britain, 1765–1776 (New York: W. W. Norton, 1972), 37–40.

- Bernard Bailyn, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1967), 84–88.

- Gary B. Nash, The Urban Crucible: Social Change, Political Consciousness, and the Origins of the American Revolution (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979), 95–98.

- Young, The Shoemaker and the Tea Party, 21–23.

- Maier, From Resistance to Revolution, 33–35.

- Breen, American Insurgents, American Patriots, 69–71.

- Young, The Shoemaker and the Tea Party, 20–22.

- Nash, The Urban Crucible, 93–96.

- Maier, From Resistance to Revolution, 34.

- Morgan and Morgan, The Stamp Act Crisis, 27–30.

- Gary B. Nash, The Unknown American Revolution: The Unruly Birth of Democracy and the Struggle to Create America (New York: Viking, 2005), 42.

- Morgan and Morgan, The Stamp Act Crisis, 32–34.

- Maier, From Resistance to Revolution, 37.

- Nash, The Urban Crucible, 101.

- Young, The Shoemaker and the Tea Party, 25.

- Breen, American Insurgents, American Patriots, 74.

- Maier, From Resistance to Revolution, 39.

- Nash, The Unknown American Revolution, 45.

- Maier, From Resistance to Revolution, 40–42.

- Breen, American Insurgents, American Patriots, 76.

- Nash, The Urban Crucible, 108.

- Morgan and Morgan, The Stamp Act Crisis, 36.

- Young, The Shoemaker and the Tea Party, 29–31.

- Gordon S. Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution (New York: Vintage, 1992), 34–37.

- Maier, From Resistance to Revolution, 43–45.

- Morgan and Morgan, The Stamp Act Crisis, 38–40.

- Breen, American Insurgents, American Patriots, 77.

- Nash, The Unknown American Revolution, 47–49.

- Wood, Radicalism of the American Revolution, 39–40.

Bibliography

- Bailyn, Bernard. The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1967.

- Breen, T.H. American Insurgents, American Patriots: The Revolution of the People. New York: Hill and Wang, 2010.

- Maier, Pauline. From Resistance to Revolution: Colonial Radicals and the Development of American Opposition to Britain, 1765–1776. New York: W.W. Norton, 1972.

- Morgan, Edmund S., and Helen M. Morgan. The Stamp Act Crisis: Prologue to Revolution. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1953.

- Nash, Gary B. The Unknown American Revolution: The Unruly Birth of Democracy and the Struggle to Create America. New York: Viking, 2005.

- Nash, Gary B. The Urban Crucible: Social Change, Political Consciousness, and the Origins of the American Revolution. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979.

- Wood, Gordon S. The Radicalism of the American Revolution. New York: Vintage, 1992.

- Young, Alfred F. The Shoemaker and the Tea Party: Memory and the American Revolution. Boston: Beacon Press, 1999.

Originally published by Brewminate, 10.21.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.