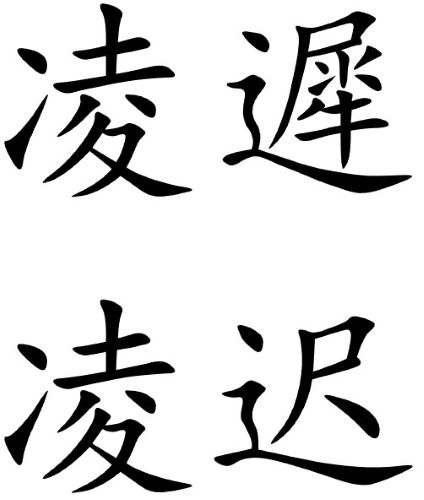

Lingchi was reserved for crimes viewed as especially heinous, such as treason.

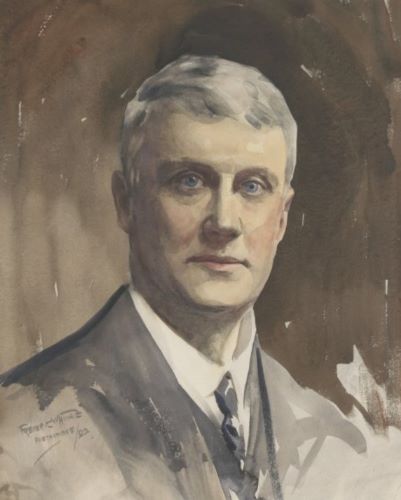

Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Lingchi, translated variously as the slow process, the lingering death, or slow slicing, and also known as death by a thousand cuts, was a form of torture and execution used in China from roughly 900 CE up until the practice ended around the early 1900s. It was also used in Vietnam and Korea. In this form of execution, a knife was used to methodically remove portions of the body over an extended period of time, eventually resulting in death.

Lingchi was reserved for crimes viewed as especially heinous, such as treason. Some Westerners were executed in this manner. Even after the practice was outlawed, the concept itself has still appeared across many types of media.

Etymology and Description

The term lingchi first appeared in a line in Chapter 28 of the third-century BCE philosophical text Xunzi. The line originally described the difficulty in travelling in a horse-drawn carriage on mountainous terrain.[1] Later on, it was used to describe the prolonging of a person’s agony when the person is being killed.[2] An alternative theory suggests that the term originated from the Khitan language, as the penal meaning of the word emerged during the Khitan Liao dynasty.[3]

The process involved tying the condemned prisoner to a wooden frame, usually in a public place. The flesh was then cut from the body in multiple slices in a process that was not specified in detail in Chinese law, and therefore most likely varied. The punishment worked on three levels: as a form of public humiliation, as a slow and lingering death, and as a punishment after death.

According to the Confucian principle of filial piety, to alter one’s body or to cut the body are considered unfilial practices. Lingchi therefore contravenes the demands of filial piety. In addition, to be cut to pieces meant that the body of the victim would not be “whole” in spiritual life after death. This method of execution became a fixture in the image of China among some Westerners.[4]

Lingchi could be used for the torture and execution of a person, or applied as an act of humiliation after death. It was meted out for major offences such as high treason, mass murder, patricide/matricide, or the murder of one’s master or employer (English: petty treason).[5] Emperors used it to threaten people and sometimes ordered it for minor offences.[6][7] There were forced convictions and wrongful executions.[8][9] Some emperors meted out this punishment to the family members of their enemies.[10][11][12][13]

While it is difficult to obtain accurate details of how the executions took place, they generally consisted of cuts to the arms, legs, and chest leading to amputation of limbs, followed by decapitation or a stab to the heart. If the crime was less serious or the executioner merciful, the first cut would be to the throat causing death; subsequent cuts served solely to dismember the corpse.

Art historian James Elkins argues that extant photos of the execution clearly show that the “death by division” (as it was termed by German criminologist Robert Heindl) involved some degree of dismemberment while the subject was living.[14] Elkins also argues that, contrary to the apocryphal version of “death by a thousand cuts”, the actual process could not have lasted long. The condemned individual is not likely to have remained conscious and aware (if even alive) after one or two severe wounds, so the entire process could not have included more than a “few dozen” wounds.

In the Yuan dynasty, 100 cuts were inflicted[15] but by the Ming dynasty there were records of 3,000 incisions.[16][17] It is described as a fast process lasting no longer than 15 to 20 minutes.[18] The coup de grâce was all the more certain when the family could afford a bribe to have a stab to the heart inflicted first.[19] Some emperors ordered three days of cutting[20][21] while others may have ordered specific tortures before the execution,[22] or a longer execution.[23][24][25] For example, records showed that during Yuan Chonghuan’s execution, Yuan was heard shouting for half a day before his death.[26]

The flesh of the victims may also have been sold as medicine.[27] As an official punishment, death by slicing may also have involved slicing the bones, cremation, and scattering of the deceased’s ashes.

Western Perceptions

The Western perception of lingchi has often differed considerably from actual practice, and some misconceptions persist to the present. The distinction between the sensationalized Western myth and the Chinese reality was noted by Westerners as early as 1895. That year, Australian traveler and later representative of the government of the Republic of China George Ernest Morrison, who claimed to have witnessed an execution by slicing, wrote that “lingchi [was] commonly, and quite wrongly, translated as ‘death by slicing into 10,000 pieces’ – a truly awful description of a punishment whose cruelty has been extraordinarily misrepresented … The mutilation is ghastly and excites our horror as an example of barbarian cruelty; but it is not cruel, and need not excite our horror, since the mutilation is done, not before death, but after.”[28]

According to apocryphal lore, lingchi began when the torturer, wielding an extremely sharp knife, began by putting out the eyes, rendering the condemned incapable of seeing the remainder of the torture and, presumably, adding considerably to the psychological terror of the procedure. Successive rather minor cuts chopped off ears, nose, tongue, fingers, toes and genitals before proceeding to cuts that removed large portions of flesh from more sizable parts, e.g., thighs and shoulders. The entire process was said to last three days, and to total 3,600 cuts. The heavily carved bodies of the deceased were then put on a parade for a show in the public.[29]

John Morris Roberts, in Twentieth Century: The History of the World, 1901 to 2000 (2000), writes “the traditional punishment of death by slicing … became part of the western image of Chinese backwardness as the ‘death of a thousand cuts’.” Roberts then notes that slicing “was ordered, in fact, for K’ang Yu-Wei, a man termed the ‘Rousseau of China’, and a major advocate of intellectual and government reform in the 1890s”.[30]

Although officially outlawed by the government of the Qing dynasty in 1905,[31] lingchi became a widespread Western symbol of the Chinese penal system from the 1910s on, and in Zhao Erfeng’s administration.[32] Three sets of photographs shot by French soldiers in 1904–05 were the basis for later mythification.

Regarding the use of opium, as related in the introduction to Morrison’s book, Meyrick Hewlett insisted that “most Chinese people sentenced to death were given large quantities of opium before execution, and Morrison avers that a charitable person would be permitted to push opium into the mouth of someone dying in agony, thus hastening the moment of decease.”

History

Lingchi existed under the earliest emperors, although similar but less cruel tortures were often prescribed instead. Under the reign of Qin Er Shi, the second emperor of the Qin dynasty, multiple tortures were used to punish officials.[33][34] The arbitrary, cruel, and short-lived Liu Ziye was apt to kill innocent officials by lingchi.[35] Gao Yang killed only six people by this method,[36] and An Lushan killed only one man.[37][38] Lingchi was known in the Five Dynasties period (907–960 CE); but, in one of the earliest such acts, Shi Jingtang abolished it.[39] Other rulers continued to use it.

The method was prescribed in the Liao dynasty law codes,[40] and was sometimes used.[41] Emperor Tianzuo often executed people in this way during his rule.[42] It became more widely used in the Song dynasty under Emperor Renzong and Emperor Shenzong.

Another early proposal for abolishing lingchi was submitted by Lu You (1125–1210) in a memorandum to the imperial court of the Southern Song dynasty. Lu You there stated, “When the muscles of the flesh are already taken away, the breath of life is not yet cut off, liver and heart are still connected, seeing and hearing still exist. It affects the harmony of nature, it is injurious to a benevolent government, and does not befit a generation of wise men.”[43] Lu You’s elaborate argument against lingchi was piously copied and transmitted by generations of scholars, among them influential jurists of all dynasties, until the late Qing dynasty reformist Shen Jiaben (1840–1913) included it in his 1905 memorandum that obtained the abolition. This anti-lingchi trend coincided with a more general attitude opposed to “cruel and unusual” punishments (such as the exposure of the head) that the Tang dynasty had not included in the canonic table of the Five Punishments, which defined the legal ways of punishing crime. Hence the abolitionist trend is deeply ingrained in the Chinese legal tradition, rather than being purely derived from Western influences.

Under later emperors, lingchi was reserved for only the most heinous acts, such as treason,[44][45] a charge often dubious or false, as exemplified by the deaths of Liu Jin, a Ming dynasty eunuch, and Yuan Chonghuan, a Ming dynasty general. In 1542, lingchi was inflicted on a group of palace women who had attempted to assassinate the Jiajing Emperor, along with his favourite concubine, Consort Duan. The bodies of the women were then displayed in public.[46]

Lingchi was also known in Vietnam, notably being used as the method of execution of the French missionary Joseph Marchand, in 1835, as part of the repression following the unsuccessful Lê Văn Khôi revolt. An 1858 account by Harper’s Weekly claimed the martyr Auguste Chapdelaine was also killed by lingchi but in China; in reality he was beaten to death.

As Western countries moved to abolish similar punishments, some Westerners began to focus attention on the methods of execution used in China. As early as 1866, the time when Britain itself moved to abolish the practice of hanging, drawing, and quartering from the British legal system, Thomas Francis Wade, then serving with the British diplomatic mission in China, unsuccessfully urged the abolition of lingchi. Lingchi remained in the Qing dynasty’s code of laws for persons convicted of high treason and other serious crimes, but the punishment was abolished as a result of the 1905 revision of the Chinese penal code by Shen Jiaben.[47][48][49]

Endnotes

- Xun, Kuang (3rd century BCE). “Chapter 28”.

- Shen, Jiaben (2006). 历代刑法考 [Research on Judicial Punishments over the Dynasties] (in Chinese). China: Zhonghua Book Company.

- Brook, Timothy; Bourgon, Jérome; Blue, Gregory (2008). Death by a Thousand Cuts. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 74..

- Morrison, J. M. (2000). Twentieth Century: The History of the World, 1901 to 2000.

- 清李毓昌命案 于保业 [The Qing Dynasty Case of Li Yuchang] (in Chinese). Jimo: Jimo Cultural Network. 2006. Archived from the original on 5 August 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- Hongwu Emperor. 大誥 [Letters Patent].

- Wen Bing. 先撥志始 [Volume One of the History].

- Shizhen. 弇山堂别集 [Yanshan Hall Collection]. Vol. 97.

- Liu Ruoyu. 酌中志 [Discretion in Chi]. Vol. 2.

- 沈万三家族覆灭记 [Destruction of the Shen Manzo family]. Suzhou Magazine 苏州杂志 (in Chinese). 25 May 2007.

- Gu Yingtai. 明史紀事本末 [Major Events in Ming History] (in Chinese). Vol. 18.

- 國朝典故·立閑齋錄 [Ming Dynasty History] (in Chinese).

- 太平天國.1 [Taiping.1]. UDN (in Chinese). 25 January 2010. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- Elkins, James (1996). The Object Stares Back: On the Nature of Seeing. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Guan, Hanqing. The Injustice to Dou E.

- Deng Zhicheng. Gu Dong Xu Ji 骨董續記. Vol. 2.

- Yu Qiao Hua Zheng Ben Mo 漁樵話鄭本末.

- Bourgon, Jérôme; Detrie, Muriel; Poulet, Regis (2004). Bourgon, Jérôme (ed.). “Execution in Canton”. Chinese Torture – Supplices Chinois (in English and French). IAO: Institut d’Asie Orientale. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- “狱中杂记” [Miscellaneous Records from Prison]. National Digital Cultural Network (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 21 June 2007.

- Shen Defu. Wan Li Ye Huo Bian 萬曆野獲編. Vol. 28.

- Zhang Wenlin. Duan Yan Gong Nian Pu 端巖公年譜.

- 台湾籍太监林表之死 [Death of the Taiwanese eunuch Lin Biao] (PDF) (in Chinese). Retrieved 3 August 2021.

- Yanbei Laoren. Qingdai Shisan Chao Gongwei Mishi 清代十三朝宫闱秘史.

- Xu Ke (1917). Qing Bai Lei Chao 清稗類鈔.

- “Lingchi – The Most Dreaded Form of Execution (Enter with Caution)” 「凌遲」最駭人的死刑5 (慎入). Pixnet. 22 April 2010. Archived from the original on 25 April 2010. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- Ji Liuqi. Ming Ji Bei Lue 明季北略. Vol. 5.

- Ji Liuqi. Ming Ji Bei Lue 明季北略. Vol. 15.

- Morrison, George Ernest. Bourgon, Jerome; Detrie, Muriel; Poulet, Regis (eds.). “Turandot”. Lyon, FR: CNRS. Retrieved 30 July 2009.

- “Death by a Thousand Cuts at Chinese Arts Centre 18th January to 23rd March”. Manchester events guide. Archived from the original on 18 April 2009. Retrieved 30 July 2009.

- Roberts, p. 60, footnote 8.

- Bourgon, Jérôme (8 October 2003). “Abolishing ‘Cruel Punishments’: A Reappraisal of the Chinese Roots and Long-term Efficiency of the Xinzheng Legal Reforms”. Modern Asian Studies. 37 (4): 851–862. doi:10.1017/S0026749X03004050. S2CID 145674960.

- Norbu, Jamyang, From Darkness to Dawn, Phayl

- Sima, Qian (91 BCE). “87”. Records of the Grand Historian (in Chinese). China.

- Ban, Gu (82 CE). “23”. Book of Han (in Chinese).

- Shen, Yue (488). “9”. Book of Song (in Chinese). China.

- Li, Baiyao (636). “3”. Book of Northern Qi (in Chinese). China.

- Ouyang, Xiu (1060). “215”. New Book of Tang (in Chinese). China.

- “中國歷史上幾次最著名的凌遲之刑” [Several of the Most Famous Lingchi Cases in Chinese History]. Sina (in Chinese). 2008. Archived from the original on 1 August 2009. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- Xue, Juzheng (974). “147”. Old History of the Five Dynasties (in Chinese). China.

- Toqto’a (1344). “61”. History of Liao (in Chinese). China.

- Toqto’a (1344). “112–114”. History of Liao (in Chinese). China.

- Toqto’a (1344). “62”. History of Liao (in Chinese). China.

- Bourgon, Jérôme (October 2003). “Abolishing ‘Cruel Punishments’: A Reappraisal of the Chinese Roots and Long-term Efficiency of the Xinzheng Legal Reforms”. Modern Asian Studies. Cambridge University Press. p. 858. JSTOR 3876529.

- Zhang, Tingyu (1739). “54”. History of Ming (in Chinese). China.

- “清华大学教授刘书林——中国第一汉奸曾国藩”. 3 March 2006. Archived from the original on 13 August 2007.

- History Office, ed. (1620s). 明實錄:明世宗實錄 [Veritable Records of the Ming: Veritable Records of Shizong of Ming] (in Chinese). Vol. 267. Ctext.

- Shen, Jiaben. Ji Yi Wen Cun – Zou Yi – Shan Chu Lü Li Nei Zhong Fa Zhe (寄簃文存·奏議·刪除律例內重法折).

- Zhao, Erxun (1928). “118”. Draft History of Qing (in Chinese). China.

- Bourgon, Jerome; Detrie, Muriel; Poulet, Regis (11 February 2004). “Turandot: Chinese Torture / Supplice chinois”. CNRS. Retrieved 30 July 2009.

Originally published by Wikipedia, 04.03.2004, under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.