Enslaved Africans were forcibly made to traverse multiple circum-Caribbean points throughout their lives.

By Dr. Jennifer Wolff

Programs and Communications Director

Center for a New Economy

Introduction

She stood in one of the patios at the Governor’s house in Bayamo, Cuba, and seemed to be between 4 and 7 years old, according to the royal officials in charge of the auction. We don’t know her name, if she was clothed or exhibited naked, or if she cried or looked bewildered. The legajo only states that she was sold as a slave to Cristóbal Venero, vecino of Bayamo, along with seven other girls and ten boys of the same approximate age for 50 pesos each. The “lot” of mulequillos was considered one of castoffs (desechos), part of a large armazón of 348 enslaved Africans that had been brought from Angola and was being auctioned off that day of March of 1631.1 We know of the girl through a lawsuit brought against the owner of the armazón; hers is one of many anonymous existences we encounter in the Atlantic slave trade through the nefarious register of their “encounter with power” (Hartman, 2008, p. 2). We do not know if she survived to grow up enslaved in Bayamo, if she was taken to Havana, or if she was reshipped and re-sold in Veracruz, Trujillo, or Cartagena.

At that time, the Spanish Caribbean was a fluid reticulate of slave routes that connected seemingly marginal locations like Bayamo with Africa and Europe, with other peripheral locations, and with the busier ports frequented by the Indies fleets in Cartagena, Veracruz, and Havana. Slave trade routes not only linked specific localities with the wider Atlantic (Wolff, 2021) but coalesced the region itself into a dense space of flows, exchanges, and interactions that were part of the vital streams of people, commodities, and capital that shaped the Atlantic in the Early Modern period (Arrighi, 2010; Mauro, 1960; Godinho, 2005). Ground-breaking studies have succeeded in mapping the place of the Caribbean within the larger contours of the transatlantic slave trade in this period (Vila Vilar, 2014; Klein, 1978; Eltis, 2001; Borucki, Eltis, and Wheat, 2020); and showing how commerce in enslaved Africans shaped specific locations throughout the region (Vidal Ortega, 2002, pp. 117-165; De la Fuente, 2008, pp. 147-185; García de León, 2014, pp. 501-575), fostered the emergence of inland continental routes (Lokken, 2013, 2020; Smith, 2020; Sierra Silva, 2020), and created circum-Caribbean and transatlantic networks over time (Eagle, 2018; Domínguez, 2021).

In this essay I will build on this rich historiographic literature and on my previous work on an ostensibly marginal place, Puerto Rico (Wolff, 2021, 2022), to trace the often haphazard maritime pathways that crisscrossed the Spanish Caribbean and formed an intricate weave of routes of re-commodification and forced mobility for enslaved Africans and black criollos during the latter part of the XVIth century and the first half of the XVIIth. As Alex Borucki, David Eltis and David Wheat (2020, pp. 16-17) have shown, the period between 1580 and 1640 conforms one of two main peaks in the history of the transatlantic slave trade (the other cresting in the XIXth century). It thus allows us to glimpse the workings of Caribbean networks within the broader Atlantic space at a key juncture. The cruel process of uprooting and commodification of captives that started in Africa-aptly described in Stephanie Smallwood’s oeuvre (2007) -did not end with the transatlantic voyage and the transformation of a “saltwater slave”-one freshly arrived-into “an American slave”- one fully integrated into the markets of commodified labor and the productive structures of early global capitalism. Deracination and re-commodification continued through a series of liquid pathways that crisscrossed the Spanish Caribbean and that repeatedly thrust the enslaved into the overlapping circuits of peoples, commodities, commercial transactions, and financial intermediation schemes that traversed the region in this period.

The Flow of Commodified Africans into the Spanish Caribbean

The girl and mulequillos that were sold in Bayamo had arrived in eastern Cuba in the Nuestra Señora del Rosario y San Francisco, a ship that had been registered in Sevilla by Spanish Juan de Burgos as taking 120 enslaved Africans from Luanda to either Cartagena or Veracruz. It had instead arrived in the Bay of Manzanillo with 335 captives in arribada forzosa (an emergency landing) alleging it was dangerously taking on water after having been robbed by Dutch corsairs. Arribadas or descaminos were a common phenomenon in the Spanish Caribbean and actually served to link locations under-served by the flota system with the vital commercial networks that traversed the Atlantic at the time (Wolff, 2022, pp. 55-114). Cartagena and Veracruz were the officially sanctioned ports for the introduction of slaves to Spanish America and between 1595 and 1610 received 94% of the import licenses (Vila Vilar, 1973, p. 562). The rest of the localities-Santo Domingo, Puerto Rico, Havana, Margarita, Riohacha, Cumaná, Honduras, and Guatemala-received a negligible number of licenses, but were actually enmeshed in an intricate weave of both real and simulated arribadas forzosas that brought hundreds of enslaved Africans to their shores and linked them to the wider transatlantic slave trade (Wolff, 2022, pp. 115-151; 2021; Eagle, 2014, 2018; Lokken, 2013, 2020; Castillo Palma, 2016; Domínguez, 2021). Santo Domingo, for example, registered 55 arribadas between January 1585 and August 1593, 12 of these transporting slaves (Eagle, 2018, p. 132). Puerto Rico registered 123 arribadas between 1580 and 1640, 58 of these linked to the slave trade; the majority of enslaved Africans bought to the island in this period came via arribadas (Wolff, 2020, p. 125; 2022, pp. 70-71).

In the case of the Nuestra Señora del Rosario and its descamino to Cuba, all of the enslaved were sold in Baracoa, a town about 68 kilometers inland from the bay of Manzanillo.2 They were auctioned in “lots,” each of a certain number of “pieces” and a certain value in pesos, calculated according to how they fit or deviated from the archetype of a pieza de Indias, that is, a flawless African body, one considered perfect for Atlantic enslavement. Francisco Díaz, a passenger who had witnessed the embarkment of the enslaved Africans in Luanda, explained that a pieza de Indias “was one that was wholly perfect, without damage or stain, without any missing teeth, or with anything that can be considered a flaw”3 (“aquella que cabalmente es perfecta, sin ningún género de daño, ni mácula ni diente menos, ni otra cosa que le pueda servir de falta”). The best “pieces” were usually between their late teens and early twenties; men were valued for their capacity for physical work, while women, for both labor and sexual pleasure (Smallwood, 2007, pp 157-166).

The “cargo” assembled in Angola included 197 children and youngsters, including four sucking infants with their mothers (“respecto de ser los más de los esclavos… de muy poca edad”). Children were often a significant part of these transatlantic human cargoes: throughout slave-trading circuits, those between 7 and 10 years old were assessed at three per “piece;” pre-teens of between 10 and 13 years, at two per “piece” (Wolff, 2022, p. 148). Officials in Luanda had thus counted “three, four and five [heads] per each licensed piece” (“pasaron tres, cuatro y cinco por una pieza de licencia”) when embarking the enslaved in the Nuestra Señora del Rosario.4 This was the reason the armazón, of 348 “pieces,” was in excess of the 120 licenses purchased by Burgos to Portuguese asentista Manuel Rodriguez Lamego.5

In Baracoa, the enslaved were re-commodified and sold as “cargo” in tiers of decreasing value. Since the size of the armazón exceeded the licenses bought in Seville, the first step was to bring the enslaved into town from the cattle ranches (“hatos”) where they had been herded in order to reassess them into taxable lots. “Eighty black males with the best bodies, countenances and figures” (“los de mejores cuerpos, rostros y talles”) between 18 and 23 years of age, and “forty pieces of black female slaves, the most beautiful and with the best bodies” (“hembras de las más hermosas y de mejores cuerpos”) between 17 and 22 years of age were deemed to be the one-hundred-and-twenty licensed “piezas de Indias.” The rest were divided into cascading tiers. First, those considered good, saleable “pieces”: males between 18 and 22; “fat and healthy” muleques y mulecones (“gordos y lozanos”) between 10 and 14 years; females “with good figures and countenances” between 17 and 22; mulecas y muleconas, “the best and most beautiful and of the best age” (“las mejores y más hermosas y de mejor edad”), between 7 and 13 years of age. All were assessed as being “pieza de Indias,” except the two lots of nineteen “fat and healthy” muleques and twenty “beautiful” mulecas, who were assessed at eight “piezas de Indias de licencia” each. Those considered as “refuse” or “rejects” (“desechos”) were assessed last: sick, dying, thin males and mulequillos (“alma en boca”); old, thin, and sick females; sick girls between four and twelve years old, some “thin and sick;” and finally, sucking babies.6

The second step in the process of Caribbean re-commodification was to put the newly arrived, enslaved Africans in the public auction block. Burgos, as the ship’s pilot and main investor, was the first to be allowed by the authorities to sell his “pieces.” Captain Pedro de la Torre Sifontes, vecino of Puerto del Príncipe, had the first choice: thirty-two “whole licensed pieces,” the “best twenty-two males and ten females,” which he bought at 150 pesos each. He bought a second “thirty-piece” lot, but since these were in “somewhat worse” condition than the preceding ones, he paid 140 pesos each (“siempre ha ido quedando los peores esclavos”). Don Fernando de Santisteban Valderas, permanent alderman of Baracoa, bought a third tier of thirty, but since they were muleques y mulecas in their early teens and had been “reduced and recalculated” (“hubo reducción y computación”), he paid 120 pesos each; Santisteban was to pay half the price cash in Baracoa and the other half in credit installments in Cartagena. Captain Juan de Frías bought the next lot of twenty-seven; these were considered “rejects” (“desechos”), so he paid 130 pesos each. A fifth lot, also of “rejects,” that of the girl and her fellow mulequillos of 4 to 7 years, was sold at 50 pesos each. The sixth and last lot was a variegated mix of sick “pieces,” also considered “refuse”: two girls of 5 or 6 years old, one feverish, the other sick with scurvy and a swollen chin; a “bearded black,” also sick with scurvy; two feverish “male pieces;” and three feverish muleques with ulcers in their mouths. Frías bought them for 60 pesos each. The rest of the armazón, consistent of breast-feeding women with their babies and “reduced” girls and boys (“mulecas reducidas” and “mulequillos de los que tres hicieron pieza”), was auctioned last.7

Like the Nuestra Señora del Rosario, each slave ship that arrived in the Spanish Caribbean was a moving device of the emerging global capitalist economy and coalesced a myriad of transatlantic commercial transactions (Rediker, 2021). The Nuestra Señora de La Luz, for example, which arrived in descamino in Ocoa, Hispaniola, from Cabo Verde with 300 enslaved Africans, was owned by a vecino of Mexico, Pedro Arriarán. The slave licenses with which the ship navigated were enmeshed in a complicated and tiered cascade of resales: originally granted by the Spanish Crown to Juan Fernández de Espinosa, Treasurer to the Queen, the licenses had been sold to two Sevilla residents, who in turn sold them to a third, who in turn sold them to a fourth, who in turn finally sold them to a resident of Canarias, who then made the deal with Arriarán to assemble the slave-buying trip to Africa and deliver the human cargo to him in Mexico. The murkiness of the multiple transactions caused the slaves to be seized in Ocoa.8

Pedro Navarro’s voyage through the Spanish Caribbean with enslaved Africans also illustrates the complex slave-trading networks and circuits that came together in the region through descaminos. In 1611, Navarro bought one hundred licenses in Lisbon in order to navigate one hundred “pieces” (“piezas de esclavos”) from Angola to Cartagena or New Spain. In 1612, however, he embarked in Luanda 221 “pieces,” including sixty-two “small pieces called muleques.” The human cargo was loaded on the ship on behalf of him, his crew, his passengers, and more than a dozen absentee retail buyers, for whom Navarro and his fellow traffickers were also acting as transatlantic intermediaries (“tres muleques… van por cuenta de Juan de Argumedo… entran cinco por cuenta de Domingo Viera”).9 Although Navarro’s dispatch from the Portuguese authorities in Luanda stated New Spain as the ships’ ultimate destination, he surreptitiously contracted his crew to sail from Angola to Havana.10 From the legal proceedings against him, we know that the “pieces” Navarro embarked in his name had been pre-ordered in Havana and were being anxiously expected there: Felipe de Guevara, vecino of the town, had ordered half of the armazón (“iba interesado”), acting on behalf of Lucas Camaño, sergeant major of the garrison in Havana; while Francisco Serralta, owner of the ship, and Mateo García, both vecinos of Seville, owned ¼ each. García had agents in Havana waiting for his part, while Serralta used Navarro as an intermediary.11

Navarro’s commercial venture took the unfortunate enslaved Africans he transported as cargo through the Caribbean. He made a first “emergency landing” in San Juan de Puerto Rico, alleging the ship was taking on water and needed provisions; he quickly left town, however, since he found it in a Holy Week lull. He then made another arribada in Baracoa, in the northeastern tip of Cuba, where he stayed for fifty days. By the time he reached Havana in August of 1613 in a third arribada his human cargo had been reduced to 154 “pieces.” Navarro told royal officials that he had not sold any slaves prior to landing, but Fulgencio de Lima, a Havana resident, later told authorities that he had heard (through the implacable rumor mill that characterized Spanish American societies at the time) that some captives had died of scurvy while some been sold in Baracoa. Other vecinos stated that about forty had apparently been disembarked in the stealth of the night on a beach upon the ships’ arrival in Havana.12

Navarro’s long transatlantic journey had made his buyers in Havana nervous. Months in advance of this arrival, Felipe Guevara had sought accommodations throughout the town for what he said were “300 negroes… he was expecting” (“300 negros… que andaba a buscar casa porque los estaba aguardando”). By April or May, however, he feared Navarro had turned rogue and had decided to sell the cargo on his own in another port-of-call. Guevara sent an associate to Jamaica and Cartagena to search for the missing trafficker and hastily sold half of his participation in the armazón to Sheriff Alonso Ferrara.13 Ferrara was a shrewd trafficker involved in the purchase, reshipment, and resale of African slaves throughout the Caribbean. With an associate, Francisco López de Piedra, he frequently brought to Cuba slaves bought in Jamaica and Puerto Rico.14

When Navarro finally arrived in Havana, the threat of an embargo by the authorities triggered a frenzy of transactions. Royal officials had accused Navarro of arriving maliciously in order to sell his cargo illegally (“vino a este puerto arribado maliciosamente y con trato hecho”) and the Bishop of Havana threatened those involved with excommunication (“que caiga fuego del cielo sobre ellos, que… les escueza de día la luna, de noche sus hijos anden mendigando”).15 Lorenzo del Rio, agent for Mateo Garcia’s heirs, promptly sold one of his “pieces” at a discount to Juan, the carpenter, and seventeen to a servant of Sheriff Ferrara with the condition that they be taken and resold in New Spain.16 Ferrara’s associate, López de Piedra, bought another twenty or thirty “pieces.” The duo sent the captives they bought to New Spain.17 Navarro himself ended re-embarking and selling seventy-six of the unfortunate Africans in New Spain, where they arrived a year and a half after being taken out of Luanda.18 We know the names of some of the seventy-eight who were sold in Havana: Lucrecia, Sebastián, Lucía , and Beatriz, all Angolas between 18 and 22 years old; Lucía, “bozal” and Bengela, 24 years of age; María, “bozal,” 12 to 14 years of age; Lorenzo, less than 5 years old.19

Multi-nodal circuits of arribadas and the trans-shipment of enslaved Africans were common phenomena in the region. Marcos Perera, for example, traveled from Angola to Brazil, with 299 enslaved Africans; he reached San Juan de Puerto Rico with 124. Of these, seventy-one were sent to New Spain to be resold. Duarte de Acosta Nogueras, for his part, traversed Puerto Rico, Jamaica, Trujillo and Campeche selling his armazón of 452 (Wolff, 2021, pp. 117, 143-147).

By 1616, Jamaica had become, according to Antonio González, factor in Havana to asentista Antonio Fernández del Vas, a regional hub: “the ships that come from Angola to New Spain and Cartagena arrive there easily and sell all the unregistered [slaves they bring], and even those that they [lawfully] bring within register.”20 In the five years between 1608 and 1613, more than 2,000 enslaved Africans had presumably been illegally brought by Portuguese merchants to Jamaica in arribadas, according to captain Agustín de Priego y Aranda, the judge who proceeded against Navarro in Havana.21 Priego thought that Ferrara and López de Piedra had bought at least 500 of these captives, whom they had brought to Havana.22 The same role of trans-Caribbean slave hub was ascribed to Campeche, Santo Domingo and Puerto Rico, where, according to the Council of Indies, traffickers “pretend to arrive in arribada, with the ships supposedly in bad shape so as not to continue their voyage; and thus, most of the slaves taken out of Guinea disappear.”23 Puerto Rico, for example, served as entry point into the Caribbean for the transshipment of enslaved Africans to Havana and then Veracruz and sustained a community of Portuguese merchants linked to the transatlantic slave trade (Wolff, 2021, pp. 134-147; 2022, pp. 115-135). Riohacha and Portobelo were also mentioned as part of these circuits for the fraudulent circulation of slaves (Vila Vilar, 2014, p. 167). The ports of the province of Honduras were also frequently used to bring slaves illegally from Cartagena, Santo Domingo, Havana, “and other parts,” according to royal officer Francisco Romero; the enslaved were brought inland and sold in Guatemala, Comayagua, and Sonsonate, where they could be re-sold to vecinos who would travel from as far as Oaxaca and Los Ángeles.24

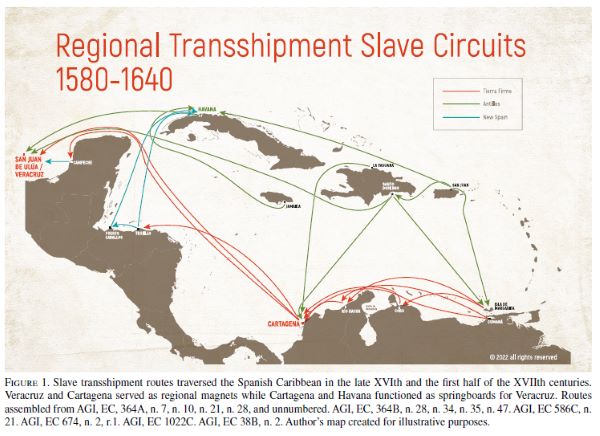

Citlalli Domínguez (2021) has posited the emergence of a Great Caribbean-Veracruz axis that from the 1620s on funneled enslaved Africans from the circum-Caribbean region to San Juan de Ulúa. From there, they would be taken to the Mexican interior (Sierra Silva, 2020, pp. 7586) or to the Pacific Coast and as far as Manila, as New Spain became integrated into the transpacific slave trade (Smith, 2020, p. 136). Based on the trajectories identified in this essay, I would suggest a non-linear, somewhat haphazard, fragmented circular pattern (Fig. 1). Veracruz and Cartagena, entryways to the dynamic mining complexes of Zacatecas and Potosí and to vigorous agricultural continental hinterlands, each effectively served as regional axis (García de León, 2014, pp. 261-262, 318-321; Vidal Ortega, 2002, pp. 31-33). The islands and circum-Caribbean littorals, ever more integrated in the emerging global markets for hides, tobacco, tinctures, ginger, and sugar through both legal and illegal commerce (Wolff, 2022, pp. 179-198; Arcila Farias, 1946, pp. 63-96: Lokken, 2020, pp. 111-118), funneled enslaved labor to their own interiors and to other peripheral circum-Caribbean locations. Both Cartagena and Havana served as intermediate re-shipment springboards for Veracruz. For the enslaved, this maelstrom of crisscrossing and overlapping circuits meant a pattern of continuous deracination, dislocation, and re-commodification.

Intra-Caribbean Circuits of Forced Mobility

In May of 1595, a black enslaved woman whose name or age we do not know arrived in San Juan de Ulúa from Cartagena along with thirty-three other enslaved men and women. They each had come from different places around the Caribbean-Santa Marta, Riohacha, La Yaguana, Santo Domingo, Margarita-before being assembled in Cartagena and brought to New Spain by seven different owners aboard the Nuestra Señora del Rosario. None of the enslaved was described as a criollo, so we presume all had been born in Africa. Following Smallwood (2007, p. 2), I admit the impossibility of actually reconstructing these broken lives but attempt to do them justice by narrating the systemic violence that transformed them into transatlantic commodities. This woman in particular had already spent a decade and a half in America, five years in Cartagena, and ten in Santo Domingo prior to her landing in New Spain. We cautiously imagine, then, that she might have been partially or fully accultured, that she spoke Spanish and may have been baptized, and that she might have developed affective ties in the places she had lived in. None of this, however, prevented her being uprooted again to be taken from Cartagena to San Juan de Ulúa by her owner, Francisco Díaz, presumably to be sold again.25 We know of her and her enslaved shipmates through a complex trail of fees or certificates, that Díaz had to show port authorities in San Juan de Ulúa in order to prove that royal duties had been paid for each of his slaves. These certificates lead us through the liquid pathways that the enslaved he forcibly took to New Spain had traversed through the Caribbean. It is interesting to note that, in contrast with the transatlantic arribadas, few of the enslaved forcibly taken through these regional routes were children. Most were young adults in their prime; many had spent a considerable number of years already in the region.

Five of the “pieces” taken in the Nuestra Señora del Rosario were “slaves from the land and nation of Angola” and had arrived in Cartagena from Africa the year before of 1594 as part of an armazón of sixty-four. Two other Angolans named Antón (20 years of age, “good height”) and Melchor (15 years, “mid-sized body”) had only recently been brought to Cartagena by a vecino of La Yaguana, Bernardo Quirós. Antón and Melchor had been originally disembarked from Africa in Santo Domingo, part of a larger contingent of slaves that Quirós himself had introduced into Hispaniola before taking the pair with him to La Yaguana. Antonio, “black slave,” also “of the land and nation of Angola” had originally arrived in Santa Marta some years prior, in 1592, as part of a larger arrival of 115 piezas; he remained a year and a half in Santa Marta before being re-shipped to Cartagena. Two other unnamed “pieces, one male, one female,” whose places of origin we do not know, had initiated their American journey through an arribada to Margarita in 1590; they had been taken to Cartagena the year after. Juan, an Angolan, twenty years of age, had arrived for his part in Santa Marta in 1589, before being shipped to Cartagena and re-shipped to San Juan de Ulúa. Fernando, a Bran, had landed in Cartagena from Cabo Verde twelve years prior, in 1583. Pedro, another Bran, had originally disembarked in Santo Domingo from Tenerife in 1593 as an enslaved cabin boy. Instead of re-embarking him on the trip back as part of the maritime crew, his owner had instead sold him in Hispaniola; we do not know when he was taken to Cartagena or under what circumstances. Ana, originally brought from Cabo Verde in the Indies fleet of 1584, had been in Cartagena for more than twelve years. Another Ana, from Biafara, 24 years, “not too tall, bent, dark black (“prieta atezada”)” was, for her part, a recent arrival: she had only disembarked in La Yaguana that the same year of 1595 and had immediately been taken to Cartagena. We can only imagine the cruelty of her former owner, who had inscribed his name, Cristobal Hernández Hermoso, either on her cheeks or on her buttocks (“carrillos”).26

In many instances, the vessels making these regional circuits transported enslaved Africans as only one of a myriad of “commodities.” Diego de Texalde (Texada, Tecalde, or Elexalde depending on the folio), for example, came to Tierra Firme with his commercial sloop in one of the Indies convoys, and rather than return with the fleet, chose to remain in the region transporting both merchandise and slaves on behalf of others between Cartagena and New Spain. In 1596 he disembarked in San Juan de Ulúa twenty “pieces of slaves” consigned to him by at least five different individuals with a payload of “merchandise.”27 The Portuguese García de Riberos brought to Margarita in arribada thirty-seven enslaved Africans from Cabo Verde alongside a luxury chair, foodstuffs, and about twenty passengers who had chartered his services to be brought from Lisbon and Santiago de Cabo Verde to Burburata. “There is not a single vessel,” said a vecino, that does not bring both slaves and passengers, while taking back to Portugal “monies, ox hides and other merchandises.”28

The entanglement of a myriad of African origins with diverse Caribbean points of entry, settlement, and transshipment was a common feature of the smaller cargoes of enslaved people that traversed these intra-regional slave routes. As Marcus Rediker (2008, pp. 105-142) has noted, each ship that made the transatlantic journey forcibly brought together a host of cultural experiences from the enslaved’s lands of origins: savvy coastal people were thrown together with agricultural folks, former warriors from emerging kingdoms with individuals from pastoral groups. According to Rediker’s mapping, over thirty distinct cultural groups in Africa served either as sources of provenance or enslavement for the transatlantic market. In the Caribbean, these heterogeneous groups would disembark in large arribadas, say, in San Juan de Puerto Rico, Santo Domingo, Margarita, or Cumaná; over the years, the enslaved would be taken in trickles to intermediate points around the region before converging in the larger sanctioned ports of Cartagena and Veracruz or in unofficial inland entryways such as Trujillo or Puerto Caballos.

For example, Antón Bran and Fernando Bañol arrived in Santo Domingo from an undefined point in Africa in 1582 in an arribada made by a ship traveling to Brazil. Nine years later they were both taken and re-sold in Margarita, only to be taken to Cartagena and San Juan de Ulúa a year and a half later.29 Similarly, Alonso, an Angolan, 20 years of age, “bent body, color loro,” arrived in Caracas in 1586; six years later he was taken to Margarita, Cartagena and finally, to San Juan de Ulúa.30 An unnamed “black slave” arrived in Riohacha from Cabo Verde in 1585; we do not know his name or how he labored there, only that he was sent to Cartagena and resold in San Juan de Ulúa ten years later, in 1595.31 Ten unnamed enslaved Angolans who were disembarked in an arribada to Jamaica in 1619 were sent to Havana four years later in 1623; they were sold in New Spain in 1625.32 Mateo, for his part, “thin of body,” a mark in his arm and a scar in his left template, had been sold in Puerto Rico in 1621 as part of an arribada that had come from Angola; he was sent two years later to Cuba and two years later again, to New Spain. The record tells us he must have been eleven years old when originally sold in San Juan de Puerto Rico.33

One wonders about the solidarities and broken nexus that could have sprung along these fragmented pathways. As Smallwood (2007, pp. 101-121) has noted, the terrible process of enslavement, forced marches, and embarkment in Africa, as well as the appalling ordeals of the transatlantic journey aboard the slave ship must have forged tragic but indelible bonds among the enslaved, ties in the construction of new diasporic identities. For example, Antonio and Domingo (the first one, “color loro,” the second, “black”), both 15 or 16 years old, Andrés, “black” and 14, María, 20 and “black,” and Isabel, 27, “short, a bit chubby,” had all been brought from Angola to Cumaná in the same ship, the Nuestra Señora del Rosario, descaminado in 1591. All five had been branded with the same property mark, two arrows which crossed each other. All converged again in 1592 when they were sent from Cartagena to San Juan de Ulúa with forty-five other slaves of different owners on the same ship, the San Juan. The paper trail and the new marks on their bodies speak about their divergent pathways: Antonio now had a cross inscribed above his left teat; his certificate showed that he had arrived in Cartagena from Riohacha, not directly from Cumaná. María, Andrés, and Isabel also had additional marks inscribed in their skins: a double five (“cinco quinas”) in the right arm and a VO above the left breast, in the case of María; several letters by the left teat, in the case of Andrés; an R above the right teat, in the case of Isabel.34 Tragically, three other enslaved Africans that converged on that same ship to San Juan de Ulúa-Gracia, Antón and an unnamed male-carried the same mark of the crossed arrows in their arms, although they had arrived two years earlier, in 1589, in another arribada to Cumaná.35 As Jesuit Antonio de Sandoval noted in 1627, shipment for Spanish-American ports was usually preceded in Africa by forced treks along “two and three hundred leagues” and the sale and resale of the captives “to three, four and more owners” in inland “fairs,” markets and collection points (Sandoval, 1627, ff. 65v-68). The two crossed arrows that by serendipity converged again in the eight enslaved bodies in the Cartagena-San Juan de Ulúa journey makes us think that they were possibly captured, bought, or branded by the same slaver or slaving group somewhere in Africa as part of their lengthy and broken pathway towards Caribbean slavery.

These routes of forced mobility crisscrossed the region, sometimes haphazardly and not necessarily traversing it from East to West. Twenty Angolans, “fourteen male and six female,” who had arrived in an arribada in Trujillo in 1616, were taken to Cuba in 1622 and only then to Mexico three years later.36 The trafficker who had brought them to Spanish America, the Portuguese Fernando de Gois y Matos, had himself traveled inland to Santiago de Guatemala, presumably with the rest of the armazón (Lokken, 2013, p. 186); in 1623 he again registered in Sevilla his intention to purchase 150 enslaved Africans in Cabo Verde and transport them to either New Spain or Tierra Firme.37 Similarly, ten “Africans from Guinea” that Portuguese Vasco Martín brought to Cartagena in 1594 were zigzagged to Trujillo and Puerto Caballos, Havana (where five were sold) and finally Mérida (where the remaining were disembarked). Martín was a resident of Mérida who seems to have had a fair share of bad luck: he traveled to Guinea as a small trader and embarked the ten enslaved Africans as part of a larger armazón assembled by seasoned mariner Martín Ruiz de Briviesca (Wolff, 2021, pp. 58, 75, 89, 102). He fell sick throughout the voyage and had to use the proceeds of the Havana sale to pay his debts; the remaining slaves were confiscated in his hometown of Mérida, as the ship had arrived without a license in an arribada.38

Not all of the enslaved that were uprooted in these intra-regional circuits were Africans. Antón, criollo of Jamaica, had been taken in 1613 to Cuba, where he was sold to Sheriff Ferrara.39 Julián, criollo from Puerto Rico, 22 years of age-“good body and form and very dark (“atezado”), with a scar in his left leg and a burnt-mark in his left teat”-was sold in Nueva Córdova, Cumaná, by his owner, Francisco López de Bejar, vecino of Puerto Rico. Hardly five years older than Julián, López de Bejar seems to have been either a merchant or a man of the sea: at 27, he prided himself in having made at least one arribada and of having traveled “around the Indies.” He sold Julián to Melchor Sánchez, vecino of Margarita, who then sent him to Cartagena to be resold in New Spain with four Africans he also owned: Alonso Angola, Madalena Bran, Gracia Angola and María Angola.40 Sánchez entrusted the sale of the five slaves to Francisco Manuel, an experienced pilot-of-the-Indies-fleet-turned-merchant who traversed New Andalucía, New Granada and New Spain dealing in textiles, wines, pearls, gold, hides and enslaved Africans.41 Manuel epitomizes the circum-Caribbean slave dealer that shaped the liquid regional pathways in which the enslaved were enmeshed as commodities in a web of commercial transactions, capital pledges, letters of debt and opportunistic exchanges.

Slave Traffickers Who Forged the Circuits

We encounter Francisco Manuel in two legal dossiers opened against him by judges Hernando Murillo de la Cerda in Campeche and Francisco Méndez de la Puebla in Cartagena. Murillo de la Cerda had been named by the Crown in 1595 to investigate arribadas and illegal commerce (“tratos y contratos con ingleses y franceses”) in Veracruz, San Juan de Ulúa, Campeche, Yucatán, and Puerto Caballos, while Méndez de la Puebla had the same mandate for Tierra Firme.42 A similar inquiry was being simultaneously conducted by judge Hernando Varela in the jurisdictions of Puerto Rico, Hispaniola, Cuba and Jamaica (Wolff, 2022, pp. 72-75; Ponce Vázquez, 2020, pp. 82-87; Deive, 1996, pp. 153-166). It was impossible for the Crown to absolutely control the flow of merchandise and people in the region.

In 1596 Murillo de la Cerda accused Manuel of having made an unlicensed disembarkment in Campeche in 1592. His ship, which had carried both merchandise and slaves, had had a purported route between Cartagena and San Juan de Ulúa, port of Veracruz. It had instead reached Campeche in arribada, with Manuel alleging that the crew lacked drinking water and that some of the enslaved had fallen sick. Murillo contended that Manuel, as pilot of the Indies fleet, was supposed to have returned to Spain with the Tierra Firme convoy, but had instead traveled illicitly to Campeche to illegally sell his goods and his slaves.43

Among the “pieces of slaves” transported by Manuel in this voyage were Julián criollo of Puerto Rico and the four Africans entrusted to him by Sánchez, five slaves that Manuel was taking on behalf of Juan de Amortegui, a vecino of Seville, and another thirty on behalf of Juan de Uribe de Apallúa. Uribe was a multi-faceted though controversial figure. Basque shipbuilder and merchant, author of seafaring accounts, and several-times commander of the Indies fleets, he was also involved in small-scale slave-dealing from the Peninsula: between 1571 and 1597 he bought fifty-two slave licenses at the same time that he dealt in wines, apparel and general merchandise (Ortiz Arza, 2019a, pp. 301-30; 2019b, p. 61-62). In the 1590’s he was brought before the Council of the Indies for having used his position while outfitting Indies fleet vessels to illegally sell 200 barrels of wine (“pipas de vino”) in New Spain.44 At about the same time, two flyboats he owned were seized in Cuba on orders from judge Méndez de la Puebla, who accused Uribe of illicitly bringing 468 barrels of wine to the ports of Havana and Santo Domingo.45 In Puerto Rico, judge Varela suspected Uribe as being behind several arribadas.46

Manuel was an associate of the powerful Uribe, serving as his intermediary, agent, and front-man in Tierra Firme. He had bought the thirty-five slaves he was carrying on behalf of Uribe and Amortegui with the proceeds of shipments of goods (“cargazón de mercaderías”) that each had separately sent the pilot from the Spanish peninsula. Manuel had sold their merchandise in Margarita, where he had bought the slaves he was now taking from Cartagena to New Spain on their behalf. The vessel’s master, Diego Ocampo, for his part, was taking fifteen “pieces of slaves” to New Spain on behalf of a Paio Pereira, who was waiting for them in San Juan de Ulúa in order to take the enslaved to Mexico City. The ship had been bought by Manuel in Cumaná on behalf of Uribe, who at a distance was, to all effects, the armador of the slave-selling trip (“va el dicho navío por cuenta y riesgo del general Juan de Uribe de Apallúa”). The ship, the San Juan, had arrived four years prior in Cumaná in a descamino from Angola.47 The journey to San Juan de Ulúa had been undertaken under the prompt of a Veracruz vecino, Gabriel Maldonado, who had written Manuel that, “blacks are fetching particularly good prices here, especially good black female ones (“negras buenas”)… Come up here, Your Grace, with the most slaves that you can, because in effect they are selling better here than there.”48 Thus, the forced transport of Julián criollo and the fifty-four enslaved Africans from Cartagena to New Spain aboard the San Juan embodied a complex entanglement of transatlantic and circum-Caribbean circuits, relations and transactions.

The slave-selling trip nearly unraveled in Campeche but did not: Pereira sued master Ocampo for arriving there instead of their agreed-upon destination, and Gonzalo Carrillo, a passenger, broke with the group and continued on his own with the nine slaves he was taking to Veracruz. Manuel, however, obtained permission from the town’s major to continue his trip to San Juan de Ulúa; he first bought and loaded 110 ox hides on behalf of Uribe.49 Hides were a regional commodity of choice for Manuel in his circum-Caribbean ventures, as were pearls, gold, and slaves, which he obtained in exchange for peninsular goods: wine, textiles, crockery, boots, hats, foodstuffs and tools.50

This particular slave-selling and ox-hide-buying-venture to Campeche and San Juan de Ulúa was, in effect, part of a six-year ongoing relationship between Manuel and Uribe. Manuel had acted as Uribe’s representative in the sale of a pearl-fishing canoe the general possessed in Riohacha. The canoe, with nine pearl-fishing slaves and a service female slave included, was sold for 6,200 pesos in pearls, which Manuel sent to Cartagena on Uribe’s behalf. As part of the transaction, Manuel had secured for the general the titularity of thirty-four pearl-fishing enslaved Africans-Francisco Biafra, Antonio Bañol, Antonio Bran, Blas Mandinga, among others-as a security deposit in case the buyers failed to produce the agreed-upon price in pearls.51 In 1590, while spending the winter in Havana, the general wrote Manuel, then in Cumaná, to send him “two hundred pearls of two to three carats” and advised him not to go to Cartagena, as his goods might be confiscated there.52

Museo Historico Nacional, Santiago, Wikimedia CommonsUribe was not Manuel’s only associate in his transatlantic web. In 1587 the pilot had made a partnership with Juan de Olano, a vecino of Sevilla, to make a slave-buying trip to Cabo Verde and the rivers of Guinea. Manuel was to take wine, foodstuffs, textiles, and tools to Santiago and buy either slaves, ivory, or sugar, depending on market conditions.53 Olano’s instructions to Manuel are worth reproducing, as they shed light on the mechanics of transatlantic trade in enslaved Africans:

You will seek to leave as soon as possible… take port [in Santiago] and unload the ship as soon as possible in order to avoid corsairs… If in Santiago you find many slaves at a good price, it would be appropriate to exchange the goods in barter for them. And it must be ensured that, even if they are more expensive, you buy young lads, and that they are well chiseled and of good disposition, that none is older than twenty-five years of age nor younger than fifteen and that a third, more or less, be females, and from a good land, like that of Bran… because good merchandise is easily sold… And if you do not find in Santiago slaves at a good price, and plenty of them, consider that it might be advantageous to make a contract with part of the goods and to send the vessel to the rivers during all of January, in order to sell the rest of the goods by barter in exchange of Bambara slaves or ivory or sugar…54

Manuel seems to have been no stranger to transatlantic slave trading. In 1584 he had arrived in Cumaná in arribada from Angola.55 This time, according to authorities, Manuel never reached the rivers of Guinea: he arrived instead in Cumaná in arribada and stayed in the region trading throughout Coro, Margarita, and Cumaná and coordinating at least one ox-hide-buying trip through Cumaná, Caracas, Curaçao, Coro, Riohacha, and La Yaguana.56

After the San Juan de Ulúa venture of 1592, Manuel must have returned to the Spanish peninsula, as he traveled back to Tierra Firme in 1594 as part of Sancho Pardo’s Indies convoy. Carrying peninsular wines, foodstuffs, and textiles, he again deviated from his licensed destination, Cumaná, and reached Coro instead in arribada. He spent several months traversing Maracaibo, Pamplona, Santa Fe, Tunja, and “many parts of the New Kingdom of Granada,” selling his goods to avid local merchants. In Cartagena, Manuel had developed some kind of link to Portuguese merchant Jorge Fernández Gramajo: in a murky incident, Manuel hid, under the stealth of the night and helped by several slaves sent by the powerful Portuguese, a “heavy” and “tawny” chest in one of Fernández Gramajo’s houses. Fernández Gramajo had initiated his commercial career through an arribada to Santo Domingo and had since become, according to Enriqueta Vila Vilar (2012, pp. 67-69), the “prototype” of an international slave dealer: the base of his fortune was the introduction of enslaved Africans from Angola, Guinea and Cabo Verde, and their transshipment to Perú. When Manuel was processed in Cartagena by Judge Méndez de la Puebla for his arribada to Coro, the authorities confiscated the mysterious chest; inside, they found gold, silver, and jewels, as well as dozens of debt letters in pesos, pearls, and gold from vecinos and merchants from Havana, Veracruz, Margarita, Riohacha, Maracaibo, New Spain, Huelva, and Madrid. Most of the obligaciones were payable to Manuel, some were payable to Uribe.57 Among the documents found in the chest was a letter from Uribe with instructions to Manuel; on the backside, the title “Memorial de negros” (“list of blacks”) and a list of names of enslaved Africans and black criollos, presumably bought and sold by Manuel on behalf of Uribe:

- Domingo Criollo

- Pedro Criollo

- Cristóbal Calabar

- Francisco Biojo

- Francisco Angola

- Rodrigo Çape

- Juan Biafara

- Mandinga

- Pedro Congo

- Francisco Angola Juan Angola

- Hernando Angola

- Gaspar Biafara Julián Criollo

- Alonso Angola

- Manuel Angola

- [stained] Congo Bastián

- Antón

- [stained] Barbas Fra Bañon

- Frasquillo

- Antonia Biafara

- Magdalena

- Gracia Ángela

- Artilla

- María

- Ana

- El negro de Men Peres [sic]

- El criollo de P amigo

- Otro negro

- Otro negro Francisco del dicho Gs

- El negro Francisco de Juan Caveo [sic]

- Antonio del dicho

- Andrés del dicho

- Diego del dicho

- Gaspar

- Alfonsillo

- Antón Gude

- Antón Barbie

- Manuel

- Pablillos

- Elba

- Domingo Criollo

- Pedro Criollo

- Antón Calabar

- El bioho Francisco

- Francisco Mulato

- Francisco Angola

- Mateo

- Mandinga

- Francisco Angola

- Hernandillo

- Juanillo

Conclusion

Between 1580 and 1640 an estimated 193,437 enslaved Africans were disembarked in the Spanish circum-Caribbean region.58 We do not know how many of these were transshipped to other points around the region beyond their initial point of entry, as the number of intra-Caribbean treks is still grossly underreported in the available literature.59 The sample cases examined for this essay have shown that forced mobility through the region’s liquid pathways seemed to be a common phenomenon among many of the captives brought into the region.

Bought and sold as commodified labor, enslaved Africans like Melchor Angola and black criollos like Julián were forcibly enmeshed in the dense reticulate of exchanges that traversed the Spanish Caribbean in the Early Modern period. Many of them were recent arrivals from Africa, but many others were either locally-born or had spent considerable time in the region. The slave routes they were made to traverse by merchants like Francisco Manuel and Pedro Navarro constituted sinews that linked seemingly isolated and marginal localities in the region to the larger flows of peoples, capital, and commodities of the Spanish Caribbean while bonding the area itself to the rapidly evolving Atlantic space. These maritime pathways of slavery and forced mobility thus render the early modern Caribbean into a geography of flows within the emerging global capitalist economy, a coherent-though shifting-social space of commodification, production, and exchange.

See endnotes and bibliography at source.

Originally published by Culture and History Digital Journal 12:2 (December 2023) under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.