Originally published by Newberry Digital Collections for the Classroom, 11.12.2013, Newberry Library, republished with permission for educational, non-commercial purposes.

Introduction

The Civil War has long served as a powerful, organizing division in American literary history. As critics Christopher Hager and Cody Marrs recently noted, 1865 has provided a nearly unquestioned periodization for students, teachers, and scholars of American literature. “American Literature to 1865,” “American Literature after 1865.” These are the standard rubrics for countless courses, anthologies, and critical works. Yet, Hager and Marrs ask, what if “as an event in literary history [the Civil War] is both a rupture and an occasion for extension?” Many celebrated writers of the 1850s (Herman Melville, Walt Whitman, Frederick Douglass) continued to produce important works during and after the war. Realism, a literary movement associated with the end of the nineteenth century, has significant precedents in antebellum literature. How would the study of nineteenth-century American literature change if we explored these continuities?

Americans wrote, published, and read a great deal about the war as it was going on and in the years that immediately followed. This literature invested the violence and trauma of the Civil War with meaning.

Drawing a firm line at 1865 may have had another effect as well: encouraging us to look away from literature on the war itself and on its immediate aftermath. The traditional American literary canon often skips from American Renaissance figures of the 1850s to late-century realists like Henry James and Edith Wharton. Yet Americans wrote, published, and read a great deal about the war as it was going on and in the years that immediately followed. Civil War literary culture included a wide variety of both popular and highbrow forms, from news of the frontlines to accounts of emancipation to patriotic songs and poems as well as countless works of fiction. This literature invested the violence and trauma of the Civil War with meaning. It helped Americans on both sides of the conflict make sense of the war and its effects.

The collection of texts here draws on a number of these genres to explore the ways that literary culture shaped the meaning of the war for people who lived through it.

Writing the War for the Union I

Northerners read about the war through many different kinds of texts, several of which appear below. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper was a popular, New York–based weekly. This cover (above), dated October 25, 1862, offers a good example of Northern war reporting in its account of Jeb Stuart’s October 10–12 raid on Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. The illustration on the bottom half of the page offers a reminder that the Civil War was not the only war the United States fought that year; it also conducted a war against Dakota (or Sioux) Indians in Minnesota, then considered the Northwest. The Civil War had placed new pressures on Indian Country. Both the Union and the Confederacy laid claim to territory outside the established states. In August of 1862, tensions over land erupted into a war between the Dakota and settlers who were soon joined by the U.S. army. Hundreds of people on both sides of the conflict died. By the end of December, most of the Dakota bands had surrendered. The United States held nearly 400 Dakota warriors prisoner and, on December 26, hanged 38 men in the largest mass execution in U.S. history. Leslie’s presents the illustration here as “a sketch by a correspondent,” but the drawing was probably embellished by a staff artist.

The final source above is from Frank Moore’s collection of anecdotes and popular poems about the war. Moore was a New York journalist who, in the 1860s, published many compilations of writing related to the war, including a 12-volume history entitled The Rebellion Record. This work opens with Abraham Lincoln’s portrait on the frontispiece.

Writing the War for the Union II

The poems here are by Herman Melville, a writer more commonly associated today with great works of fiction, such as Moby Dick and “Bartleby the Scrivener.” Melville responded to the Civil War by writing poetry, publishing this book, Battle-Pieces and Aspects of the War, the year after the war had ended. The book is dedicated “to the memory of the three hundred thousand who in the war for the maintenance of the Union fell devotedly under the flag of their fathers.” It offers a lyric history of the war, moving chronologically through battles and other important events. The poems presented below express both devotion to the national cause and ambivalence about the meaning of war itself.

The poem “Shiloh” refers to a battle that took place in Tennessee on two days in April 1862. It began with a strong Confederate strike, but the Union army turned the battle on the second day and defeated the Confederate forces. Each side suffered over 1,700 killed and over 8,000 wounded. At the time, it was the bloodiest battle in U.S. history. A requiem is a chant or dirge that lays the dead to rest.

The last two poems are from a section entitled “Verses Inscriptive and Memorial.” The first refers to the Battle of Baton Rouge in August 1862, when Confederate forces tried and failed to recapture that city. The last refers to the presentation of captured, Confederate flags to Union authorities after General Robert E. Lee’s surrender.

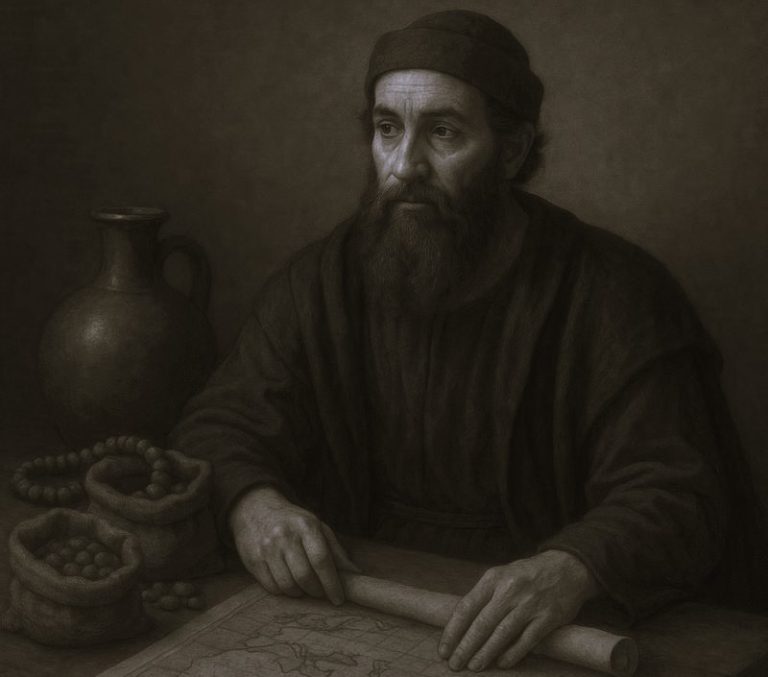

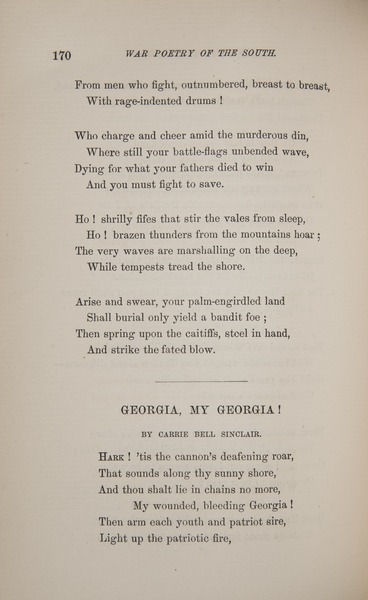

War Poetry of the South

Publishing conditions in the South were dramatically different from those in the North at the time of the Civil War. As historian Alice Fahs explains, before the war, the North had many more printing presses than the South. Much of the literature that Southerners read was published in the North. The war exacerbated this disparity: the South experienced severe shortages of paper and ink as well as personnel to run what presses remained south of the Mason-Dixon line. War Poetry of the South, the anthology excerpted here, reflects these conditions: it was published in New York the year after the war ended.

The book’s editor, William Gilmore Simms, was a novelist, poet, and magazine editor from Charleston, South Carolina, whose work had been nationally celebrated earlier in the century. In the years leading up to the war, however, Simms took a stridently proslavery position and fervently embraced the Confederate cause, driving away much of his Northern audience. During the war, Simms lost two children and his wife, and saw his plantation burned twice, destroying his 10,000-volume library.

Simms gleaned the poems in War Poetry of the South from various Southern magazines and newspapers as well as from his private correspondence. The poems selected below are all by women who were well-known poets at the time.

Literature of Emancipation

For many people, the most important effect of the Civil War was that it ended slavery. The North did not enter the war with the goal of freeing the slaves; it fought to preserve the Union. But the South seceded in order to protect the institution of slavery. And in the North, the literature on slavery and emancipation played an essential role, first, in promoting the cause of abolition and, then, in helping Northerners understand the significance of emancipation when it did arrive. For these reasons, the literature of emancipation is integral to the literature of the war itself.

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin was the single most influential literary text in the antislavery cause. It was first published serially in 1851–1852 in the antislavery newspaper the National Era. When it appeared in book form later in 1852, its popularity “had no precedent,” writes critic Elizabeth Ammons. “The book sold more copies than any book except the Bible.” The illustrations above appeared in that first edition. They shed light on the ways that Northern readers imagined the suffering that slaves experienced and the struggle for freedom.

The monthly Anglo-African Magazine was “the first literary magazine produced by and for the black community,” the scholar Eric Gardner notes. Its editor, Thomas Hamilton, published the magazine in New York in 1859 and 1860 along with a newspaper, the Weekly Anglo-African, which ran from 1859 to 1865. Hamilton laid out in the magazine’s first issue his intention to feature African American writers and to reach African American readers. “We need a Press—a press of our own,” he wrote, and a forum for “our own advocacy.” The magazine included fiction and poetry as well as political and social commentary. The excerpts above are from the magazine’s final issue. William J. Wilson was a prolific essayist who often published under the pseudonym Ethiop. (The name commonly referred to African Americans in the nineteenth century and evoked African contributions to human civilization.) Frances Ellen Watkins was one of the most famous African American writers and activists in the nineteenth century.

The final two poems above suggest some of the ways that the now-canonical writers Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson responded to slavery. Whitman first published Leaves of Grass in 1855 but continued to revise and reissue the work throughout his life. The poem by Emily Dickinson was first published posthumously in this 1890 edition edited by Thomas Wentworth Higginson and Mabel Loomis Todd. Higginson was an abolitionist and colonel who led the First South Carolina Volunteers, a regiment of black soldiers composed mainly of former slaves. Higginson and Todd added the title “Emancipation” to Dickinson’s untitled poem upon publishing it.

Women and the Home Front

In the North and South alike, women took up new responsibilities when their fathers, husbands, and sons left home to serve in the war. Traditionally female domestic chores took on new meanings during wartime. Middle-class women stitched shirts and flags, while working-class women in factories and sweatshops produced uniforms and cartridge bags by the millions. Women ran family farms, nursed the wounded, spearheaded fundraising initiatives, and became increasingly visible in society and the economy. During the war, as before it, many women continued to be voracious readers of periodicals and novels.

The illustrations and captions here suggest some of the ways that women’s wartime work shaped literary culture in the North. The Harper’s Weekly illustration (above) portrays women sewing soldiers’ uniforms, caring for the wounded, and washing laundry in a military camp.

Patriotic envelopes, such as the two above, were enormously popular and printed in thousands of different designs.

Finally, the novel Little Women (above) was published just a few years after the war ended. The mother and daughters of the March family try to contribute to the war effort while their father is serving as a chaplain in the U.S. Army. When the father returns home wounded, he requires care from his wife and daughters.

Selected Sources

- Brownlee, Peter John and Daniel Greene, curators. Home Front: Daily Life in the Civil War North. Exhibition co-organized by the Newberry Library and the Terra Foundation for American Art. 2013.

- Coviello, Peter. “Battle Music: Melville and the Forms of War” in Melville and Aesthetics, edited by Samuel Otter and Geoffrey Sandborn (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), 193–212.

- Fahs, Alice. The Imagined Civil War: Popular Literature of the North & South, 1861–1865 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001).

- Gardner, Eric. Unexpected Places: Relocating Nineteenth-Century African American Literature (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2009).

- Hager, Christopher and Cody Marrs. “Against 1865: Reperiodizing the Nineteenth Century.” Journal of Nineteenth-Century Americanists 1, no. 2 (Fall 2013): 259–284.

- Terra Foundation for American Art. The Civil War in Art: Teaching and Learning through Chicago Collections. 2012.

- Wilson, Ivy. “‘Are You Man Enough?’: Imagining Ethiopia and Transnational Black Masculinity.” Callaloo 33, no. 1 (2010): 265–277.

- Wimsatt, Mary Ann. “William Gilmore Simms.” American National Biography Online (Feb. 2000).

By Dr. Hana Layson

Manager of School and Educator Programs

Portland Art Museum

By Dr. Justine S. Murison

Associate Professor of English

University of Illinois