Not everyone thought the free market approach to Capitol spaces was a positive addition to the building.

Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

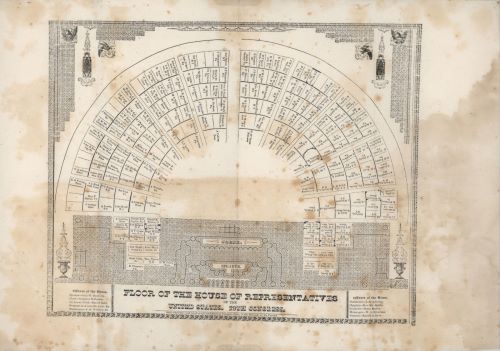

You could buy a coffin, a deer skin, or a slice of pie as you strolled the Capitol 150 years ago. “It is a grand, vaulted, arcaded street,” one visitor enthused, “and during the session filled with a jostling, hurrying throng.” Tourists bought guidebooks. Business visitors snapped up seating charts to identify Representatives at their House Chamber desks. Members of Congress grabbed a quick lunch. Reporters filed stories and bet on horses at the telegraph stand. And the young Pages bought doughnuts, cookies, and every kind of sweet they could get their hands on.

Not everyone thought the free market approach to Capitol spaces was a positive addition to the building. The New York Times railed against “apple-vendors, dealers in cheap trumpery, cigar-sellers, and other petty trades-people.” But the facts of life in Washington were economic, and merchants who could make money in the busy building would do so, even selling coffins there during the Civil War. Foreigners found it depressing. The center of American democracy “is now dedicated,” Frances Trollope wrote, “to the sale of tarts and gingerbread—of very bad tarts and gingerbread.”

Writers noted the bazaar atmosphere that prevailed in the Capitol in the 19th century, and some accounts embroidered the sparse documentation. But who were the entrepreneurs who set up shop in the Capitol? Most went unnamed, but a few distinctive characters made an impression over the years, leaving behind clues to their working lives, and even some of their wares.

‘Little Buttercup’

Buttercup, a “venerable dame, smoking a pipe,” sold apples for decades just outside the House Chamber. Reporters sometimes called her “the old apple woman,” but her real name was Hannah. Like many longtime sellers, Hannah was easy to find in the same spot every day. “Promptly at 12 o’clock,” the Bismarck Daily Tribune reported, “old Hannah comes trudging into the House corridor with her basket of red and yellow apples, carrying her little footstool on which she seats herself in one of the window casements.” In her corner of the Capitol, she counted titans of the legislature, including future Speakers Thomas Brackett Reed and Joe Cannon, among her customers.

Jennie’s Pies

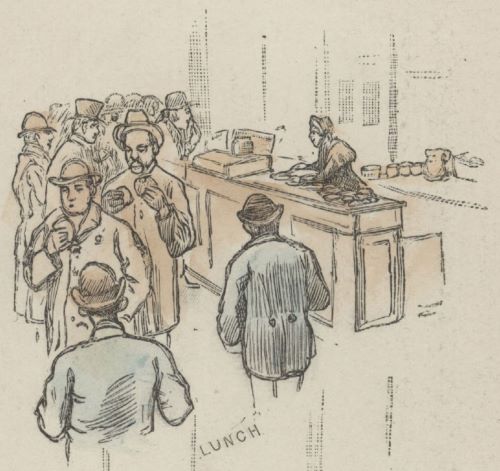

The Civil War brought Jennie, a soldier’s widow and home baker, to the House, where she set up a lunch counter. Informal refreshment stands, the food trucks of the 19th century, abounded in the Capitol. Occasionally, legislators complained that the “effect [of desserts] on the small boys—the pages about this House—is bad.” Perhaps the Representatives objected more to the crowds around Jennie’s famous sandwich and pie counter.

Pie was a quintessentially American food, popular in all regions. Jennie kept a dozen varieties because “nearly all the Members eat pie,” as she told one reporter: grape pie for Jim Buchanan, lemon for Ways and Means Committee Chairman Roger Mills, pineapple for Representative Melvin Boothman, mince for Representative Tim Campbell, and huckleberry for Representative Edward Funston. Representative William Mason ate an entire half pie (always coconut), every day at Jennie’s stand. “Any man who doesn’t like pie,” he declared loudly to the Louisville Courier-Journal, “is worse than a liar.”

Mr. Wellborn’s Twin

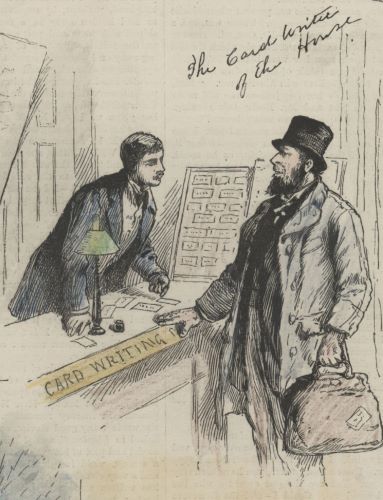

Good penmanship earned one enterprising man a spot just outside the House Chamber door. While two doorkeepers bustled about, guarding the door and carrying visitors’ business cards to the Members, a cardwriter set up shop to assist visitors in need of a calling card with his stack of paper and fine penmanship. Many journalists described the anonymous calligrapher, and although his name eluded them, his face was distinctly familiar. Representative Olin Wellborn of Texas so closely resembled the “frowsy-headed little fellow” that he was occasionally asked to write a card.

Clara Morris

Clara Morris was the most famous and enduring figure among the Capitol merchants. A wizened figure dressed in black, she sold autographed photos, guidebooks, and miniature models of the Washington Monument made of pulped dollar bills at her stand just off the Rotunda. She made an impression on politicians and tourists alike, shaking her iron-grey curls and fringed red plaid cape as she alternately charmed and berated passing Members of Congress, all in a vaguely foreign accent. Visitors posited that she came from South Carolina, or Louisiana, or maybe Germany or France, long ago. She was often called “the little French woman,” but appears to have come from New Orleans, where she left her millinery business at the start of the Civil War. She kept her money carefully obscured behind a poverty-stricken persona, while purchasing property in Washington and reportedly sending her children to the finest schools in the land.

Evicting Vendors

Not everyone cheered the easy access to food, souvenirs, and telegraphs. Beginning in the 1860s, the House debated clearing the corridors of tradespeople, or at least confining them to the basement. Speakers bemoaned their inability to evict vendors who each, it seemed, had a patron in Congress. Finally, iron-fisted, apple-eating Speaker Thomas Brackett Reed had enough of crowded halls and the fairground atmosphere. In 1890, as part of his sweeping institutional reforms, Reed cleared the corridors of counters, card-writers, and apples.

Most merchants left, grumbling but compliant. Clara Morris, true to her stubborn character, refused to go. She taunted Reed, saying that he was a “scoundrel, brute, and bulldog” and did not have the audacity to toss out an old woman. He did, and with his order to the Sergeant at Arms, officials dismantled Clara Morris’ stand, the last one to leave the House.

Bibliography

- Frances Trollope, Domestic Manners of the Americans (London: Whittaker, Treacher & Co., 1832)

- New York Times, February 27, 1861

- Congressional Record, February 15, 1866

- Washington Post, December 12, 1877

- Daily Register, March 1, 1886

- Nashville Daily American, December 25, 1887

- Boston Daily Globe, February 23, 1888

- St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 15,1888

- Louisville Courier Journal, August, 26, 1888

- Bismarck Daily Tribune, June 7, 1890

- St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 1, 1890

- Washington Post, July 3, 1890

- Milwaukee Sentinel, July 13, 1890

- Boston Daily Globe, September 14, 1890

- Los Angeles Times, December 27, 1890.

Originally published by the Office of the Historian, United States House of Representatives, 05.14.2018, to the public domain.