The supplements industry has built a multi-billion-dollar empire on false claims.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

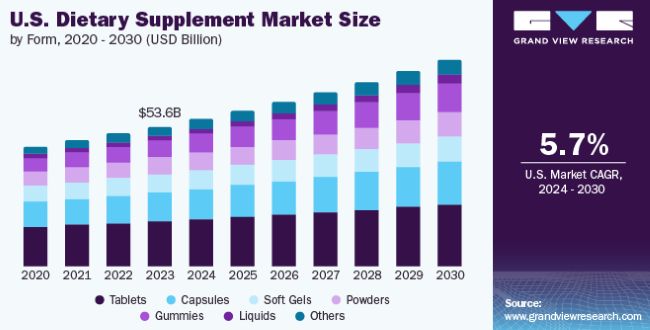

In the sprawling world of consumer health, few sectors have grown as dramatically and as controversially as the dietary supplements industry. With revenues exceeding $150 billion globally in recent years and projected to surpass $230 billion by 2027, the supplement market has become one of the most profitable arms of the wellness economy.1 Yet beneath its glossy packaging and wellness rhetoric lies a troubling pattern: many of its products are backed by little to no rigorous scientific evidence, and the industry frequently relies on misinformation and disinformation to market its offerings. This essay explores the economic magnitude of the supplements industry, its regulatory loopholes, and the ways in which misleading claims have been used to entice consumers, often at the expense of public health and scientific integrity.

The Financial Scale of the Supplements Industry

The global dietary supplements market includes a wide range of products—vitamins, minerals, herbal extracts, amino acids, and enzymes—that are promoted as health enhancers. In the United States alone, the industry reached $63 billion in 2023, and demand continues to grow, driven by trends in wellness, aging populations, and heightened health awareness following the COVID-19 pandemic.2 Companies like Herbalife, GNC, and Amway have become household names, supported by aggressive marketing and expansive distribution networks, including multilevel marketing (MLM) schemes.

The industry’s profitability is partly a result of low production costs combined with high retail markups. Unlike pharmaceuticals, supplements do not require expensive clinical trials or FDA approval before reaching the market.³ This deregulated environment allows manufacturers to invest more in marketing than in research, often allocating significant resources to celebrity endorsements, influencer promotions, and pseudoscientific jargon that appeals to consumer anxieties and aspirations.

Regulatory Loopholes and Lax Oversight

A pivotal factor in the supplements industry’s unchecked growth has been the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) of 1994. This U.S. law effectively exempted supplements from the strict regulatory framework imposed on pharmaceutical drugs. Under DSHEA, supplement manufacturers are not required to prove the efficacy or safety of their products before selling them, and the burden of proof lies on the FDA to show that a product is unsafe.4 This reversal of responsibility has enabled the proliferation of unverified health claims and ingredients of dubious origin.

Moreover, labeling practices are remarkably permissive. Companies are allowed to use “structure/function” claims such as “supports immunity” or “boosts energy” without substantial evidence, provided they include a disclaimer that the FDA has not evaluated the statement.5 This tactic enables marketers to imply therapeutic benefits without explicitly stating them—thus evading regulatory scrutiny while still influencing consumer behavior.

The Role of Misinformation and Disinformation

Misinformation (false or misleading information shared without intent to deceive) and disinformation (deliberately deceptive content) are rampant in the supplement sector. These practices exploit consumer trust in science and medicine, often by cherry-picking studies, misrepresenting data, or citing outdated research.

For example, the claim that vitamin C can prevent or cure the common cold has persisted for decades, primarily due to Linus Pauling’s controversial advocacy, despite numerous large-scale clinical studies showing no consistent benefit.6 Yet many supplement companies continue to market high-dose vitamin C products using this unsubstantiated premise.

Worse still is the exploitation of scientific jargon and the appropriation of legitimate-sounding language. Terms like “clinically tested,” “doctor recommended,” or “pharmaceutical grade” are routinely used in advertising, often without any supporting evidence.7 In some cases, companies fabricate studies, invent nonexistent research institutes, or manipulate study designs to produce favorable outcomes.8 The widespread use of testimonial marketing further blurs the line between anecdotal evidence and empirical validation, substituting personal stories for scientific proof.

Social media has exacerbated the problem. Influencers with little to no scientific training promote supplements as miracle cures, often in partnership with brands that reward them for sales. The echo chamber effect allows disinformation to spread rapidly and widely, reinforcing beliefs that are unsupported or outright contradicted by the scientific community.9

Public Health Implications

The proliferation of misleading supplement claims is not just a matter of consumer deception—it poses tangible risks to public health. Overconsumption of vitamins like A and E has been linked to increased mortality in some populations, and unregulated herbal products have been associated with liver damage, kidney failure, and other severe outcomes.10 Additionally, the false sense of security provided by supplements can lead individuals to forgo proven medical treatments or delay seeking proper care.

Perhaps more insidious is the erosion of trust in science itself. When consumers repeatedly encounter products labeled as “scientifically proven” only to experience no benefit—or worse, harm—it contributes to broader skepticism of legitimate scientific and medical authority.11 This distrust is particularly dangerous in times of public health crisis, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic, when misinformation about “immune-boosting” supplements abounded, sometimes overshadowing evidence-based prevention measures like vaccination and masking.12

Toward Reform and Accountability

Despite growing awareness, reform efforts have been slow and inconsistent. Some advocates have called for amending DSHEA to require pre-market testing and approval, or at least mandatory registration and disclosure of ingredients and studies. Others propose the establishment of a third-party verification system to evaluate claims and ensure product safety.

Organizations such as the U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP) and NSF International have attempted to fill this gap by offering voluntary certification programs, but these are not uniformly adopted and are often unknown to the average consumer.13 Increased public education, media literacy, and scientific transparency are essential if consumers are to make informed choices in a market so rife with manipulation.

Conclusion

The supplements industry has built a multi-billion-dollar empire on the premise of health enhancement, yet it often delivers little more than empty promises—and sometimes dangerous consequences. Its financial success is intricately tied to a regulatory framework that favors manufacturers over consumers and to a marketing strategy that thrives on misinformation and disinformation. Unless stronger oversight and public awareness are brought to bear, this lucrative illusion will continue to flourish at the expense of science, trust, and human health.

Endnotes

- Grand View Research. Dietary Supplements Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report By Ingredient, 2023.

- Zion Market Research. Global Dietary Supplements Market Size & Share Expected to Reach $230 Billion by 2027, 2023.

- Nestle, Marion. Food Politics: How the Food Industry Influences Nutrition and Health. University of California Press, 2013.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. “Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994.” https://www.fda.gov.

- Cohen, Pieter A. “Hazards of Hindsight — Monitoring the Safety of Nutritional Supplements.” New England Journal of Medicine 382 (2020): 107–110.

- Hemilä, Harri, and Elizabeth Chalker. “Vitamin C for Preventing and Treating the Common Cold.” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2013.

- Geller, Adriane I., et al. “Emergency Department Visits for Adverse Events Related to Dietary Supplements.” New England Journal of Medicine 373 (2015): 1531–1540.

- Caulfield, Timothy. The Cure for Everything: Untangling Twisted Messages about Health, Fitness, and Happiness. Beacon Press, 2013.

- Broniatowski, David A., et al. “Weaponized Health Communication: Twitter Bots and Russian Trolls Amplify the Vaccine Debate.” American Journal of Public Health 108, no. 10 (2018): 1378–1384.

- Navarro, Victor J., et al. “Liver Injury from Herbal and Dietary Supplements.” Hepatology 60, no. 4 (2014): 1399–1408.

- Ioannidis, John P.A. “Why Most Published Research Findings Are False.” PLOS Medicine 2, no. 8 (2005): e124.

- Niburski, Kendra, and Jonathan B. Niburski. “COVID-19, Vitamin D, and Public Misunderstanding.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 192, no. 33 (2020): E951–E952.

- Office of Dietary Supplements, National Institutes of Health. “Third-Party Certification for Dietary Supplements.” https://ods.od.nih.gov.

Originally published by Brewminate, 05.30.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.