The Mexican–American War demonstrates that information has long functioned as a tool of state power rather than a neutral backdrop to political decision-making.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: War by Narrative, Not Accident

The Mexican–American War has often been framed as an unfortunate but inevitable clash between two nations driven by geography, destiny, and unresolved borders. Such interpretations obscure the central role played by political narrative in transforming a localized and ambiguous military encounter into a full-scale war. In 1846, the United States did not stumble into conflict through misunderstanding alone. Rather, war was made possible through deliberate framing that presented aggression as defense and provocation as victimhood.

At the center of this narrative construction stood President James K. Polk. Upon learning of a skirmish between U.S. and Mexican forces in disputed territory along the Texas border, Polk moved swiftly to define the meaning of the event before alternative interpretations could take hold. In his message to Congress in May 1846, he asserted that Mexico had “shed American blood upon American soil,” a phrase that carried immense rhetorical power while quietly eliding the unresolved status of the land itself. By collapsing territorial ambiguity into moral certainty, Polk transformed a contested encounter into a national outrage.

This framing was not incidental. Polk’s administration had long pursued territorial expansion, viewing war with Mexico as a means rather than a risk. The political effectiveness of his narrative lay in its simplicity. By asserting that the United States had been attacked, Polk shifted the burden of justification away from executive decision-making and onto the presumed necessity of national defense. Congress was thus invited to respond emotionally and patriotically rather than analytically, narrowing the space for dissent or factual scrutiny.

What follows argues that the Mexican–American War was not the product of accidental escalation but of intentional narrative construction. Misinformation and disinformation operated not only through false statements, but through selective emphasis, strategic omission, and the rapid consolidation of a single authoritative account. By examining how Polk and his administration shaped public understanding of the conflict’s origins, this study situates the war within a longer history of information as an instrument of power rather than a neutral conveyor of truth.

Territorial Ambiguity and the Texas Question

The roots of the Mexican–American War lay in a deliberately unresolved territorial question following the annexation of Texas in 1845. While the United States recognized Texas as an independent republic prior to annexation, Mexico did not. More critically, even among American policymakers there was no settled agreement on Texas’s southern boundary. Mexico maintained that the border lay at the Nueces River, while the United States increasingly asserted the Rio Grande as the rightful border. This disagreement was not a minor cartographic dispute but a fundamental question of sovereignty.

The ambiguity surrounding the border was politically useful. By asserting the Rio Grande as Texas’s boundary, the Polk administration effectively claimed a large swath of territory that Mexico had long governed and populated. This claim rested less on historical precedent than on strategic convenience. Earlier Texan governments had exercised little to no authority south of the Nueces, and even American diplomats privately acknowledged the weakness of the Rio Grande claim. Nevertheless, ambiguity was allowed to harden into official policy.

Rather than seeking negotiated resolution, the Polk administration treated uncertainty as leverage. Diplomatic overtures were accompanied by military positioning, signaling that territorial claims would be enforced rather than debated. The lack of a clearly demarcated boundary created conditions in which confrontation could be framed as unavoidable. When violence occurred, the administration could plausibly argue that American forces had been attacked within U.S. territory, despite the contested nature of that assertion.

This strategic exploitation of uncertainty illustrates how territorial ambiguity functioned as a precursor to narrative control. By declining to clarify borders through diplomacy, the administration preserved the flexibility to interpret events in ways that favored escalation. The Texas question thus became not merely a background condition of the war, but an active instrument in its creation, demonstrating how unresolved geography can be transformed into political opportunity.

Polk’s Political Objectives and Expansionist Ideology

Polk entered the presidency with an unusually clear and ambitious territorial agenda. Unlike many of his predecessors, Polk was a single-term president by design, intent on achieving specific expansionist goals within a limited window of power. Central among these objectives were the acquisition of California, the settlement of the Oregon boundary, and the consolidation of U.S. claims in the Southwest. War with Mexico was not an unforeseen risk attached to these ambitions but a foreseeable instrument through which they could be realized.

Polk’s expansionism was grounded in the ideology of Manifest Destiny, a doctrine that framed territorial growth as both inevitable and morally justified. While often presented as a diffuse cultural belief, Manifest Destiny functioned politically as a powerful rhetorical tool. It allowed expansion to be cast as fulfillment rather than aggression, transforming territorial seizure into national progress. Polk repeatedly invoked this logic in both public statements and private correspondence, revealing an executive mindset that equated restraint with failure.

Importantly, Polk distinguished between diplomacy as performance and diplomacy as outcome. He authorized negotiations with Mexico while simultaneously preparing for military confrontation, signaling that peaceful resolution was acceptable only if it yielded desired territorial concessions. When diplomatic efforts failed to produce immediate results, this failure was treated not as a reason for compromise but as justification for escalation. The appearance of negotiation thus served to legitimize subsequent force.

Polk’s political calculations were also shaped by domestic considerations. Expansion promised to strengthen Democratic dominance, satisfy southern and western constituencies, and secure Polk’s place in history as a decisive leader. These incentives encouraged speed and decisiveness over caution. The framing of Mexican resistance as hostility rather than sovereignty defense became essential. War could then be portrayed not as conquest but as reluctant necessity.

The ideological clarity of Polk’s objectives complicates later narratives that depict the Mexican–American War as an accident of miscommunication or mutual misunderstanding. Expansion was not an abstract aspiration but a concrete policy aim pursued through calculated risk. Manifest Destiny provided the moral vocabulary, but executive intent supplied the direction. Together, they formed a political framework in which conflict was not merely anticipated but effectively engineered.

Troop Deployment as Strategic Provocation

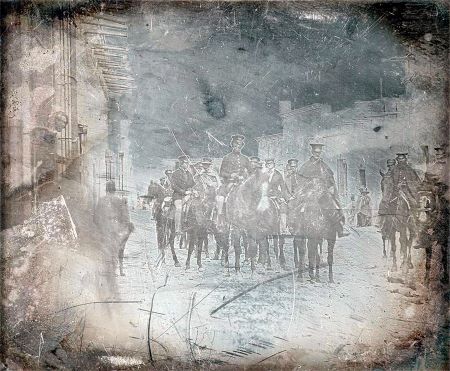

The movement of U.S. troops into the contested border region between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande was a decisive step in transforming political tension into military confrontation. In early 1846, President Polk ordered General Zachary Taylor to advance his forces southward into territory long administered by Mexico but newly claimed by the United States. This deployment was not defensive in any conventional sense. It placed American soldiers directly in a zone, at Rancho de Carricitos, where armed conflict was not only possible but likely.

Polk’s decision rested on a calculated reading of risk. By positioning troops in disputed territory, the administration created a situation in which any Mexican response could be framed as aggression against the United States. The presence of American forces functioned as a political signal rather than a military necessity. It asserted sovereignty without resolving the underlying dispute, ensuring that violence, if it occurred, could be narratively controlled from Washington.

General Taylor himself recognized the volatility of the situation. Correspondence from the period reveals awareness that the advance could provoke hostilities. Yet these concerns did not alter policy. The administration’s willingness to accept or even invite confrontation suggests that troop deployment served a strategic narrative function. Military movement became a means of testing and shaping political outcomes rather than preventing conflict.

When a skirmish did occur in April 1846, the administration was prepared to interpret it in the most advantageous terms. The clash between Mexican cavalry and a U.S. patrol, known as the Thornton Affair, was immediately framed as an unambiguous attack on American forces operating within national territory. The prior decision to advance troops made this interpretation plausible to a domestic audience, even though the land’s status remained contested. Geography was thus converted into rhetoric.

This episode illustrates how military action can operate as a form of political communication. The deployment of troops did not merely precede the narrative of war; it enabled it. By placing soldiers where conflict would carry symbolic weight, the Polk administration ensured that violence would speak in a language favorable to executive aims. Troop movement, in this context, was not preparation for war but preparation for justification.

“American Blood on American Soil”: Constructing the Incident

President Polk’s phrase “American blood on American soil,” delivered in his May 11, 1846 message to Congress, became the moral fulcrum upon which the war turned. With those words, a complex and disputed border conflict was reduced to a stark narrative of national victimhood. The language was carefully chosen. It asserted territorial certainty where none existed and transformed a localized skirmish into a symbolic violation of national sovereignty. The claim was not merely descriptive; it was declarative, defining reality through executive authority.

What Polk omitted was as important as what he stated. He did not acknowledge that the skirmish occurred in territory claimed by both nations, nor did he explain that U.S. forces had been ordered into that contested zone by his own administration. By presenting the encounter as an unprovoked Mexican assault, Polk severed cause from consequence. The movement of American troops disappeared from the narrative, replaced by a simplified account of aggression and innocence.

This rhetorical strategy relied on the power of immediacy. Polk framed the incident as a fait accompli requiring urgent response rather than careful investigation. Congress was not invited to examine the chain of events that led to the clash, only its emotional significance. The invocation of spilled blood short-circuited debate, appealing to honor, duty, and national pride rather than geographic or diplomatic nuance.

The phrase also functioned as a moral shield. By asserting that violence had already been inflicted upon the United States, Polk implied that war was no longer a choice but an obligation. Any hesitation could be construed as weakness or betrayal. In this framing, questions about territorial legitimacy became distractions, and dissent became suspect. The narrative narrowed the range of acceptable political responses before deliberation could begin.

Contemporary critics immediately recognized manipulation at work. Whig opponents, including a young Abraham Lincoln, questioned the factual basis of Polk’s claim. Lincoln’s later Spot Resolutions challenged the president to identify the precise location where blood had been shed, implicitly exposing the weakness of the “American soil” assertion. Yet these objections gained little traction in the charged atmosphere Polk had created. The narrative had already done its work.

The construction of the incident demonstrates how disinformation need not rely on outright falsehood. Polk’s statement was rhetorically true only within the framework he himself had established. By redefining contested land as unquestionably American and erasing the administration’s role in provoking confrontation, the president transformed ambiguity into certainty. The result was not a misunderstanding of events, but a successful act of narrative engineering that carried the nation into war.

Congressional Response and the Limits of Dissent

Congress’s response to Polk’s war message was swift and revealing. Within days, legislators approved a declaration recognizing that a state of war existed, effectively endorsing the president’s framing of events without demanding independent investigation. The speed of the vote reflected not only partisan alignment but the power of the narrative already established. By the time Congress convened, the terms of debate had been narrowed to whether the nation would respond forcefully to an alleged attack, not whether the attack itself had been engineered.

Party loyalty played a decisive role in suppressing scrutiny. Democrats largely accepted Polk’s account, while many Whigs harbored private doubts but hesitated to oppose a war framed as defensive. Political costs loomed large. To question the president’s claim risked accusations of disloyalty or indifference to American lives. In this climate, factual ambiguity was subordinated to political expediency, and caution was recast as obstruction.

Dissent did exist, but it was constrained and marginalized. A small group of Whigs, most notably Abraham Lincoln, attempted to challenge the administration’s narrative through procedural means. Lincoln’s Spot Resolutions sought to force clarity about the location of the initial clash, implicitly exposing the weakness of the “American soil” claim. Yet these efforts gained little traction in Congress or the press, overwhelmed by wartime momentum and patriotic fervor.

The congressional response illustrates a structural vulnerability within democratic systems during moments of crisis. When executive narratives are accepted as authoritative and time is framed as scarce, legislative oversight weakens. The Mexican–American War thus reveals how misinformation and disinformation can succeed not through censorship alone, but through speed, pressure, and the strategic narrowing of debate. Congress did not merely authorize war; it ratified a story that left little room for dissenting truth.

The Role of the Press in Amplifying Executive Claims

The American press of the 1840s operated within a highly partisan environment, one that significantly shaped how the Mexican–American War was presented to the public. Newspapers were often openly aligned with political parties, and editorial independence as a professional norm had not yet fully developed. In this context, presidential statements carried extraordinary weight. Polk’s narrative of Mexican aggression was rapidly reproduced across Democratic-leaning papers, frequently without skepticism or verification.

Rather than functioning as an investigative check on executive power, much of the press served as a transmission mechanism for official claims. Reports echoed Polk’s language, emphasizing “American blood” and framing the conflict as a defensive response to foreign hostility. Geographic ambiguity and diplomatic context were rarely explored in detail. The repetition of the administration’s phrasing across multiple outlets gave the appearance of consensus, reinforcing the legitimacy of the president’s account through sheer volume.

This pattern was not universal. Some Whig-affiliated newspapers expressed unease or criticized the rush to war, but their reach was limited compared to the dominant pro-administration press. Moreover, dissenting views struggled to compete with the emotional force of wartime rhetoric. In an era before rapid fact-checking or independent reporting from the battlefield, the press relied heavily on government sources, allowing executive framing to shape public understanding almost unchallenged.

The press’s role in the lead-up to the war demonstrates how misinformation can be amplified without fabrication. By privileging official statements and minimizing critical inquiry, newspapers helped convert political narrative into public belief. The result was not a press deceived by power, but one structurally inclined to reinforce it. In amplifying Polk’s claims, the press became an active participant in the construction of consent for war.

Misinformation vs. Disinformation: Intent and Outcome

Distinguishing between misinformation and disinformation is essential to understanding how the Mexican–American War was justified and sustained. Misinformation refers to the spread of inaccurate or incomplete information without deliberate intent to deceive. Disinformation, by contrast, involves the strategic shaping or withholding of information to produce a specific political outcome. The historical record surrounding the war suggests that while misinformation circulated widely among the public, disinformation played a decisive role at the executive level.

President Polk’s public statements cannot be dismissed as mere misunderstandings of a complex situation. The administration possessed detailed knowledge of the disputed status of the Texas border and the risks inherent in troop deployment. Internal correspondence and policy decisions reveal awareness that U.S. forces were operating in territory claimed by Mexico. Yet this context was excluded from official messaging. The selective presentation of facts indicates intentional narrative construction rather than accidental misrepresentation.

The administration’s use of disinformation did not depend on fabricating events. The skirmish that occurred in April 1846 was real. What was manipulated was its meaning. By asserting territorial certainty where none existed and by omitting the provocations that preceded the clash, the administration transformed a foreseeable encounter into an alleged act of foreign aggression. Disinformation thus operated through framing rather than falsehood, shaping interpretation rather than inventing facts.

At the same time, misinformation spread organically among the public and within Congress. Many citizens and legislators accepted the president’s claims in good faith, lacking access to alternative accounts or the means to verify them. Newspapers amplified official language, further blurring the distinction between reporting and repetition. This combination of deliberate executive framing and uncritical dissemination created an information environment in which dissenting interpretations struggled to gain traction.

The outcomes of this information strategy were profound. Disinformation at the executive level enabled rapid mobilization for war, while misinformation among the public sustained support for it. Together, they produced a self-reinforcing cycle in which early assumptions hardened into accepted truth. Once war was underway, the costs of revisiting foundational claims increased, discouraging retrospective scrutiny.

The Mexican–American War thus illustrates how intent and outcome intersect in the use of information as a political tool. Executive disinformation does not require universal deception to succeed. It requires only enough credibility, speed, and institutional reinforcement to define the initial narrative. By the time contradictions emerge, the consequences of belief have already been set in motion.

Consequences: Territorial Gain and Moral Cost

The immediate outcome of the Mexican–American War was a dramatic expansion of United States territory. Through the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, the United States acquired vast lands including present-day California, Nevada, Utah, and parts of Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Wyoming. These gains fulfilled Polk’s expansionist objectives almost exactly as envisioned, validating, at least in material terms, the political strategy that had carried the nation into war. Territory, ports, and continental reach were secured in a remarkably short span of time.

Yet these gains came at a profound moral and political cost. The war inflicted significant human suffering, particularly on Mexican civilians and soldiers, and entrenched hostility between the two nations that would persist for generations. For many contemporaries, including prominent American critics, the conflict raised troubling questions about the legitimacy of expansion achieved through provocation and narrative manipulation. The success of the war did not erase doubts about the means by which it had been justified.

Domestically, the war intensified sectional tensions within the United States. The acquisition of new territories reignited debates over the expansion of slavery, destabilizing the fragile political compromises that had held the Union together. What had been framed as a unifying defensive war instead accelerated divisions that would culminate in civil war little more than a decade later. The moral ambiguity surrounding the war’s origins compounded these tensions, as critics linked territorial conquest to the erosion of republican principles.

The precedent set by the war extended beyond territorial policy. It demonstrated that executive narrative, once accepted, could legitimize far-reaching action with minimal accountability. The success of Polk’s strategy suggested that public consent could be manufactured through selective disclosure and rhetorical certainty. This lesson would not be lost on later administrations confronting the challenge of mobilizing support for conflict.

In retrospect, the Mexican–American War stands as a cautionary example of how territorial gain can obscure ethical consequence. The land acquired reshaped the nation’s future, but the methods employed to secure it left enduring questions about truth, power, and responsibility in democratic governance. Expansion achieved through narrative control carried costs that could not be measured in miles alone.

Historical Memory and Retrospective Reckoning

In the decades following the Mexican–American War, public memory of the conflict softened and simplified its origins. Early celebratory narratives emphasized national growth, military valor, and the fulfillment of continental destiny, often marginalizing questions about provocation and legitimacy. School texts, popular histories, and commemorative accounts framed the war as a regrettable but necessary episode in national expansion, muting contemporary dissent and ethical critique.

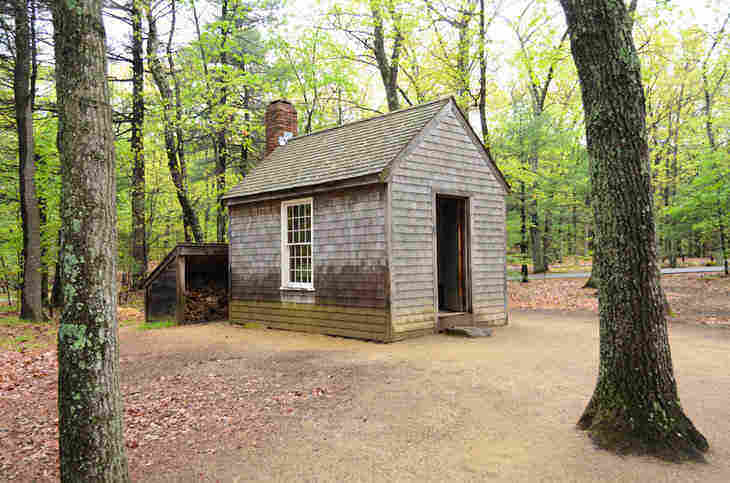

Scholarly reassessment emerged more slowly. Nineteenth-century critics such as Abraham Lincoln and Henry David Thoreau were long treated as moral outliers rather than serious analysts of executive power. Only in the twentieth century did historians begin systematically reexamining the documentary record, presidential correspondence, and congressional debates that revealed how deliberately the conflict had been framed. This shift reflected broader changes in historical methodology, including greater skepticism toward official narratives and increased attention to power dynamics.

Even so, the war’s informational dimensions have remained unevenly emphasized in public discourse. Territorial outcomes are widely remembered; narrative construction is not. The persistence of simplified explanations illustrates how misinformation can outlast the conditions that produced it. Once embedded in national memory, foundational stories resist correction, especially when they align with broader myths of progress and exceptionalism.

Retrospective reckoning does not require anachronistic condemnation, but it does demand historical clarity. The Mexican–American War offers a case study in how executive framing can shape both immediate policy and long-term memory. Reexamining the war through the lens of misinformation and disinformation restores agency to historical actors and reminds us that the past was contested in its own time, even when later generations forgot that contestation.

Conclusion: When Information becomes a Weapon

The Mexican–American War demonstrates that information has long functioned as a tool of state power rather than a neutral backdrop to political decision-making. President Polk did not rely on crude falsehoods to bring the nation to war. Instead, he employed selective disclosure, rhetorical certainty, and strategic omission to define events before they could be independently examined. By shaping how Americans understood the origins of violence, the administration transformed a contested border skirmish into a moral imperative for national action.

This case reveals how disinformation operates most effectively when it aligns with institutional authority and public expectation. Polk’s narrative succeeded not because it was universally believed to be accurate, but because it was delivered with speed, confidence, and presidential legitimacy. Once Congress and the press accepted the framing, alternative interpretations were marginalized, and factual ambiguity was rendered politically irrelevant. Information became a weapon precisely because it was trusted.

The long-term consequences of this dynamic extend beyond the war itself. The precedent established in 1846 demonstrated how executive power could mobilize public consent through narrative control, reducing democratic deliberation to affirmation rather than inquiry. The erosion of scrutiny during moments of crisis exposed a structural vulnerability within republican governance, one that would reappear in later conflicts justified through similarly constrained information environments.

Revisiting the Mexican–American War through the lens of misinformation and disinformation does more than correct the historical record. It restores agency to those who questioned the war in real time and underscores the enduring responsibility of citizens and institutions to interrogate claims of necessity. When information becomes a weapon, the defense of truth becomes not merely an intellectual exercise, but a civic obligation.

Bibliography

- Eisenhower, John S. D. So Far from God: The U.S. War with Mexico, 1846–1848. New York: Random House, 1989.

- Greenberg, Amy S. A Wicked War: Polk, Clay, Lincoln, and the 1846 U.S. Invasion of Mexico. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2012.

- Heidt, Stephen J. “Presidential Power and National Violence: James K. Polk’s Rhetorical Transfer of Savagery.” Rhetoric and Public Affairs 19:3 (2016: 365-396).

- Hietala, Thomas R. Manifest Design: Anxious Aggrandizement in Late Jacksonian America. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1985.

- Holt, Michael F. The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party: Jacksonian Politics and the Onset of the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Lincoln, Abraham. “Spot Resolutions.” U.S. House of Representatives, December 22, 1847.

- Meinig, D. W. The Shaping of America: A Geographical Perspective on 500 Years of History, Vol. 2: Continental America, 1800–1867. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1993.

- Merk, Frederick. Manifest Destiny and Mission in American History: A Reinterpretation. New York: Vintage Books, 1963.

- Merry, Robert W. A Country of Vast Designs: James K. Polk, the Mexican War, and the Conquest of the American Continent. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2009.

- Polk, James K. “Message to Congress on the State of Relations with Mexico.” May 11, 1846. In A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents, edited by James D. Richardson. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1897.

- —-. The Diary of James K. Polk During His Presidency, 1845–1849. Edited by Milo Milton Quaife. Chicago: A. C. McClurg & Co., 1910.

- Schudson, Michael. Discovering the News: A Social History of American Newspapers. New York: Basic Books, 1978.

- Smith, Justin H. The War with Mexico. 2 vols. New York: Macmillan, 1919.

- Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, February 2, 1848. U.S. National Archives.

Originally published by Brewminate, 01.07.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.