By redefining disagreement as wrong thinking, Maoist authority did not merely suppress alternative views or marginalize critics within an accepted field of debate; it expelled them.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: When Error Becomes Moral Disease

During the Cultural Revolution, political disagreement in the People’s Republic of China was no longer treated as a contest of ideas or even as a punishable offense in the conventional sense. Under Mao Zedong, dissent was reframed as a condition of inner corruption, described through the language of moral sickness and ideological impurity. To think incorrectly was not merely to misunderstand policy or misread history. It was to reveal a defective moral state. Error itself became diagnostic, and once diagnosed, it no longer required engagement. The accusation of “wrong thinking” functioned as a totalizing judgment, expelling the critic from the realm of rational participation.

This transformation rested on a fusion of ideology and virtue that left no space for neutral disagreement. Maoist thought did not present itself as one interpretive framework among others, but as the distilled expression of revolutionary truth, inseparable from moral rectitude. Correct ideas were not simply accurate. They were pure, disciplined, and aligned with the ethical destiny of the revolution. Incorrect ideas were not merely mistaken. They were diseased, polluted by bourgeois influence or counterrevolutionary contamination. Within this framework, intellectual error could not be separated from moral failure. To question Maoist doctrine was to expose oneself as ethically compromised, politically unreliable, and socially dangerous. Argument became irrelevant because the issue was no longer what was said, but what kind of person could say it. Thought itself was moralized, and once moralized, it became subject to judgment rather than discussion.

The Cultural Revolution intensified this logic by transforming diagnosis into a mass social practice. Accusations of wrong thinking did not require proof in any conventional sense. They were self-validating. To deny the charge was to confirm it. To attempt explanation was to demonstrate deeper corruption. Public denunciations, struggle sessions, and forced confessions functioned not as debates but as rituals of moral exposure. Once branded irrational or ideologically sick, the accused ceased to exist as a participant in reality itself. They were no longer interlocutors. They were symptoms.

Maoist China represents a critical moment in the history of pathologized dissent, one in which ideological devotion masqueraded as rational clarity. By converting disagreement into moral disease, Maoist power insulated itself from challenge while preserving the appearance of revolutionary righteousness and moral certainty. The Cultural Revolution did not simply silence critics through fear or violence. It redefined them as incapable of thought, rendering their claims unintelligible before they could be heard. In doing so, it reveals how regimes that claim absolute moral truth do not need to answer dissent. They only need to diagnose it, transforming opposition into evidence of corruption and power into a self-confirming vision of reality.

Maoist Ideology and the Fusion of Truth and Virtue

Maoist ideology fused epistemology and morality in a way that made disagreement structurally illegitimate. Truth was not defined as a conclusion reached through inquiry, debate, or evidence, but as a quality inherent in revolutionary alignment. To understand the world correctly was to stand on the correct moral side of history. Knowledge and virtue were inseparable. This fusion meant that intellectual error could never be neutral. To be wrong was already to be morally compromised, and moral compromise implied political danger.

This ideological framework drew selectively on Marxism but transformed it into something more rigid and absolutist. Whereas classical Marxism treated ideology as historically conditioned and subject to critique, Maoism recast revolutionary truth as immediate, transparent, and self-evident to those who were morally aligned. Theory ceased to function as a tool for analysis and became instead a test of loyalty and purity. Correct understanding was expected to arise naturally from proper class position and revolutionary devotion, not from sustained reasoning or critical examination. Those who questioned policy or interpretation were not displaying analytical independence. They were revealing ethical deviation, a failure of revolutionary character rather than an alternative reading of circumstances.

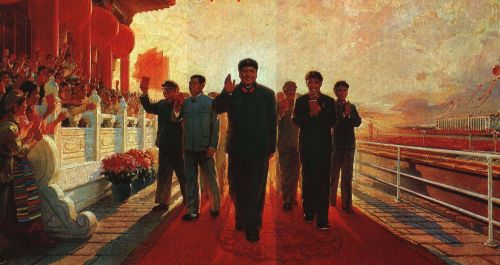

Under Mao’s leadership, this moralization of truth became increasingly personalized. Mao’s interpretations were not merely influential contributions within a theoretical tradition. They were treated as definitive expressions of historical necessity. To agree with Mao was to demonstrate moral clarity and ideological health. To disagree was to display impurity, confusion, or resistance to the revolutionary process itself. Because Maoist thought claimed to embody both the authentic will of the people and the objective direction of history, dissent appeared not as an alternative perspective but as an act of defiance against reality. The possibility that Mao might be wrong could not be entertained without destabilizing the moral foundations of the revolution, so disagreement had to be explained as corruption rather than considered as argument.

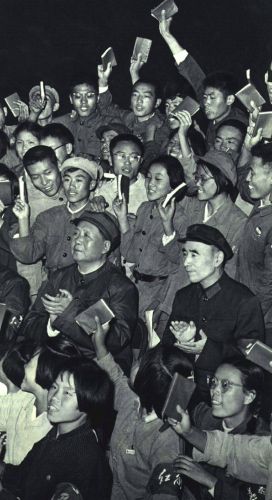

This fusion of truth and virtue also reshaped the standards by which individuals were judged. Correct belief was visible not only in words but in posture, emotion, and enthusiasm. Revolutionary sincerity became a moral performance. Passion signaled clarity. Certainty signaled health. Doubt, hesitation, or interpretive complexity suggested contamination. The ideal Maoist subject did not wrestle with contradiction or ambiguity. He embraced clarity with visible conviction. Ambivalence was not treated as reflection or intellectual caution, but as evidence of moral weakness and ideological drift.

Because truth was moralized in this way, it could not be debated without appearing corrupt. Argument presupposes the possibility that multiple positions might be considered in good faith and tested through reason. Maoist ideology denied that premise outright. To argue with wrong thinking was to grant it a legitimacy it did not deserve and to risk ideological contamination in the process. Engagement itself became suspect. The proper response to error was exposure, denunciation, and correction, not discussion. Persuasion was unnecessary because error was already understood as moral failure. Debate was dangerous because it implied uncertainty where none was permitted.

The result was an ideological environment in which certainty replaced inquiry as the highest intellectual virtue. Correctness was measured by alignment rather than reasoning, by devotion rather than understanding. Once truth and virtue were fused, dissent lost its status as thought altogether. It became evidence of inner failure. Maoist ideology prepared the ground for the Cultural Revolution by redefining disagreement as moral disease, ensuring that opposition could be dismissed, punished, and erased without ever needing to be understood.

“Wrong Thinking” as Moral and Cognitive Corruption

In Maoist China, “wrong thinking” was not treated as an error to be corrected through explanation, evidence, or counterargument. It was framed as a form of inner corruption that distorted both moral judgment and cognitive perception. To think incorrectly was to be misaligned with revolutionary truth, and that misalignment was understood as a defect of character rather than a mistake of reasoning. Wrong thought did not describe what someone believed so much as what kind of person they were. The category itself collapsed belief, intention, and identity into a single judgment, ensuring that disagreement could never remain external to the self. Once labeled, wrong thinking marked an individual as fundamentally unreliable, regardless of context, intent, or consistency.

This framing drew heavily on moral language. Wrong thinking was described as poisonous, polluted, rotten, or diseased, metaphors that implied internal decay rather than external disagreement. Such language suggested that dissent originated from contamination by bourgeois values or counterrevolutionary influence rather than from experience, analysis, or conscience. Error was not situational or contextual. It was internal and enduring. Once identified, it marked the individual as permanently suspect, regardless of repentance or explanation. The metaphor of disease implied that wrong thinking could spread, deepen, and recur, justifying continuous surveillance and repeated correction.

Cognitive corruption and moral corruption were treated as inseparable. An individual who held incorrect ideas was assumed to lack the capacity to perceive reality properly. Misjudgment was not explained by limited information, fear, or competing interpretation. It was explained by ideological sickness. This assumption allowed Maoist authority to dismiss criticism without examination. If the mind itself was impaired, there was nothing to debate. Argument presupposed a shared reality. Wrong thinking denied that such common ground existed, severing the possibility of mutual understanding in advance.

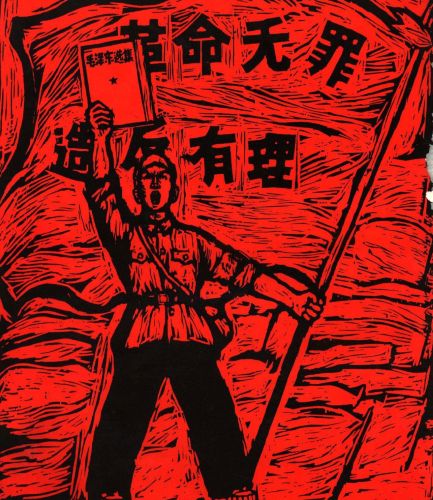

Under Mao Zedong, this logic became a central feature of political discourse and mass mobilization. Mao frequently described ideological struggle as a battle against incorrect ideas that threatened the health of the revolution. Wrong thinking was not merely an obstacle to progress or a misunderstanding to be clarified. It was an active danger that weakened collective strength and invited counterrevolution. Because the revolution was framed as morally pure and historically necessary, any deviation had to be explained as corruption rather than disagreement. Cognitive error became proof of ethical failure, and ethical failure justified coercive intervention in the name of purification.

The accusation of wrong thinking required no demonstration in the ordinary sense. It functioned as a self-sealing judgment. To deny it was to show further corruption. To attempt explanation was to display rationalization. Silence could be interpreted as concealment or internal resistance. The accused could not occupy a position of epistemic credibility because credibility itself was defined by ideological alignment. Wrong thinking therefore operated as a total category, one that foreclosed defense by defining every possible response as additional evidence of guilt.

By treating dissent as moral and cognitive corruption, Maoist power achieved a decisive form of insulation. Critics were expelled not only from political legitimacy but from reality itself. They were no longer mistaken interlocutors or ideological opponents. They were diseased minds requiring exposure, correction, and, if necessary, eradication. This transformation allowed authority to bypass persuasion entirely. Once disagreement was pathologized as corruption, the work of governance shifted from answering claims to purifying thought, completing the conversion of political conflict into moral diagnosis and rendering opposition unintelligible as thought.

The Cultural Revolution as Diagnostic Campaign

The Cultural Revolution functioned not merely as a political purge or mass mobilization, but as a nationwide diagnostic campaign aimed at identifying and exposing ideological illness. Its purpose was not to adjudicate competing visions of socialism or resolve theoretical disagreements, but to locate wrong thinking wherever it might be concealed. The campaign assumed in advance that corruption existed and that it was widespread, embedded within families, schools, cultural institutions, and even the Communist Party itself. The task of the revolution was therefore not persuasion but detection. Society was reorganized around the search for symptoms, transforming everyday life into a continuous process of ideological examination.

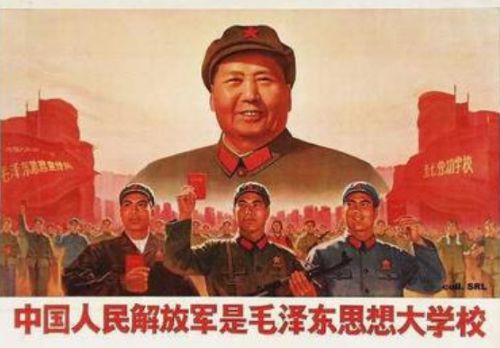

Red Guards served as the primary diagnostic agents of this campaign. Lacking formal authority, legal training, or ideological consistency, they were nonetheless empowered to judge ideological health based on behavior, speech, family background, reading habits, and emotional expression. Their authority did not rest on evidence in any conventional sense, but on revolutionary fervor understood as moral clarity. Accusation itself became proof. To be denounced was to be exposed. The absence of fixed standards made diagnosis infinitely flexible, allowing virtually anyone to be classified as sick if circumstances demanded it. This instability was not a flaw but a feature, enabling the campaign to adapt rapidly and expand without limit.

Struggle sessions became the central ritual through which diagnosis was publicly performed. These events were not debates or hearings, but ceremonies of exposure designed to force the accused to demonstrate awareness of their own corruption. Confession was the desired outcome, not because it clarified truth, but because it confirmed diagnosis. Resistance indicated deeper illness. Emotional breakdown signaled recognition. The purpose was not to establish what had been thought or said, but to produce visible submission to the category of wrong thinking.

Violence functioned within this framework as purification rather than punishment. Beatings, humiliation, public shaming, and forced labor were justified as necessary treatments for ideological sickness. Suffering was framed as corrective, capable of burning away impurity and restoring revolutionary health. The more extreme the deviation, the harsher the treatment required. In this way, brutality was moralized. It became evidence not of excess or failure of control, but of seriousness and commitment. Violence demonstrated the regime’s willingness to cleanse thought, not merely suppress dissent, and reinforced the idea that moral disease demanded physical intervention.

These practices reveal the Cultural Revolution as an exercise in moral epidemiology. Society was scanned, classified, and purged according to diagnostic logic. Guilt preceded investigation. Diagnosis replaced explanation. The campaign did not seek to convince the population of Maoist truth through argument. It sought to render all alternatives unintelligible by redefining them as illness. In doing so, it completed the conversion of political struggle into moral pathology, transforming revolution into a permanent process of ideological triage.

Social Contagion and the Fear of Ideological Infection

Maoist discourse treated wrong thinking not as a private failing but as a contagious threat capable of spreading through contact, association, and imitation. Ideological error was imagined as something transmissible, moving through families, classrooms, work units, and neighborhoods. This framing transformed dissent into a collective danger rather than an individual deviation. Once wrong thinking was understood as infectious, the goal of the Cultural Revolution expanded from correcting individuals to protecting the social body itself. Prevention became as important as punishment.

The language of infection drew on familiar revolutionary metaphors and biological imagery. Wrong ideas were described as poisonous weeds, malignant growths, or corrosive influences that weakened the collective from within. Such metaphors carried an implicit logic of urgency and eradication. Exposure itself became dangerous. Listening to criticism, associating with suspected individuals, or failing to denounce visible deviation could invite suspicion of contamination. Ideological purity required distance, vigilance, and constant demonstration of hostility toward impurity. The safest position was not quiet neutrality but visible aggression against those marked as ideologically diseased. Fear of infection reorganized social behavior around avoidance, denunciation, and preemptive displays of loyalty.

This logic reshaped relationships at the most intimate level. Families were fractured as children were encouraged to denounce parents, and spouses were pressured to prove ideological independence through public rejection of one another. Loyalty to the revolution took precedence over kinship, friendship, or trust. Association became evidence. To know the wrong person, to hesitate in condemning them, or to display sympathy could be read as signs of shared sickness. Social bonds were no longer sources of solidarity. They became vectors of risk.

Work units and schools functioned as surveillance environments structured by this fear. Political study sessions doubled as diagnostic screenings. Silence during criticism meetings could suggest hidden infection. Excessive enthusiasm could function as prophylaxis. Individuals learned to monitor not only their own thoughts but the thoughts of others, reporting deviation as a form of collective self-defense. The boundary between vigilance and paranoia eroded, producing a culture in which suspicion appeared responsible and trust appeared reckless.

The fear of ideological infection also justified isolation as a moral necessity rather than a punitive measure. Those accused of wrong thinking were separated physically and symbolically from the community through reeducation campaigns, rural exile, or confinement. Isolation was framed as hygiene, a way of preventing spread while attempting cure. The language of treatment masked the reality of exclusion, stigma, and social death. Reintegration, when it occurred, was conditional and fragile, always subject to renewed suspicion. Once labeled, an individual remained a potential carrier, permanently marked by prior exposure to ideological disease.

By treating dissent as contagious, Maoist power closed the remaining space for debate entirely. One does not argue with infection. One contains it, isolates it, and eradicates it. This logic eliminated the need to engage claims or evaluate arguments, replacing intellectual contest with quarantine. Ideological infection became a justification for permanent mobilization, ensuring that fear itself sustained the system. In this environment, disagreement could no longer appear as thought or interpretation. It appeared only as threat, something to be isolated before it could spread, confirming power’s authority by denying dissent any standing within reality.

Loyalty as Moral Sanity

Within Maoist China, loyalty was not merely a political posture or a measure of obedience to authority. It became the primary indicator of moral and psychological health. To affirm Maoist doctrine, to display revolutionary fervor, and to align one’s emotions with the demands of the moment were taken as evidence of inner soundness. Sanity was no longer defined by independent judgment, coherence of reasoning, or ethical reflection, but by ideological attunement. The morally healthy subject was one whose thoughts, feelings, and public expressions harmonized seamlessly with revolutionary truth. In this framework, loyalty functioned as a diagnostic category, marking the boundary between health and sickness, clarity and corruption.

This redefinition of sanity extended beyond explicit statements of belief into demeanor, tone, and affect. Visible passion signaled clarity. Certainty signaled virtue. Doubt suggested weakness. Hesitation implied contamination. Emotional restraint could be interpreted as hidden resistance. Individuals learned that belief alone was insufficient; it had to be performed convincingly. Loyalty became legible through ritualized displays of devotion, slogans, public confessions, and denunciations. Moral sanity was not a stable condition but a status that had to be demonstrated continuously, renewed through participation in collective judgment.

The inversion this produced was profound and destabilizing. Capacities commonly associated with moral seriousness (reflection, ambivalence, ethical discomfort, or the recognition of suffering) were recoded as symptoms of wrong thinking. To notice contradiction or injustice was not a sign of conscience but of sickness. Psychological health was defined as the absence of internal conflict with Maoist reality. The healthiest mind was one that experienced no friction between ideology and lived experience, no tension between doctrine and violence, no dissonance between revolutionary claims and personal loss. Acceptance became therapeutic. Emotional flattening became adaptive. Resistance, even silent or internal, became pathology.

By collapsing loyalty into moral sanity, Maoist power completed the insulation of authority from critique. Disagreement no longer appeared as reasoned dissent or alternative interpretation. It appeared as evidence of inner defect. The state did not need to argue with critics or disprove their claims. It needed only to demonstrate their lack of moral health. Once sanity itself was defined by obedience, truth ceased to persuade. It diagnosed.

The Erasure of Intellectual Argument

Once wrong thinking was established as a moral and psychological condition, intellectual argument ceased to function as a meaningful activity in Maoist China. Debate presupposes that competing claims can be weighed, assessed, and revised through reason, evidence, and shared standards of judgment. Maoist ideology rejected that premise outright. If dissent was evidence of sickness, then engagement was not only unnecessary but fundamentally misguided. Argument risked legitimizing error by treating it as thought rather than pathology. To respond substantively would have implied that disagreement occupied the same epistemic terrain as truth. The proper response to dissent was therefore not rebuttal, clarification, or persuasion, but exposure and correction. Intellectual exchange was replaced by moral intervention.

This shift fundamentally altered the status of language itself. Words spoken by those accused of wrong thinking were stripped of their semantic content and reinterpreted as symptoms. A critique of policy was not evaluated for coherence or accuracy. It was decoded for signs of ideological contamination. Meaning no longer resided in what was said, but in who said it and what moral condition they were presumed to inhabit. Intellectual exchange collapsed into moral classification, rendering argument impossible before it could begin.

The erasure of argument also reshaped historical memory in lasting ways. Individuals purged during the Cultural Revolution were remembered not for the substance of their ideas, but for their alleged corruption and moral failure. Their writings were destroyed, suppressed, or recontextualized as evidence of deviation rather than contributions to political or intellectual life. Dissenting positions vanished from the record, replaced by simplified narratives of exposure, confession, and correction. Because arguments were never answered, they were never preserved. Diagnosis functioned as a tool of historical deletion, ensuring that alternative interpretations left no trace capable of being recovered or reconsidered. Silence became archival.

Power no longer needed to persuade because persuasion implied uncertainty. Authority was maintained through certainty reinforced by diagnosis. By converting disagreement into illness, Maoist rule eliminated the intellectual conditions necessary for challenge. Argument was not defeated. It was rendered unintelligible. Once thought itself became suspect, the silence that followed was not merely imposed. It appeared rational, necessary, and morally justified.

Internalization, Fear, and Moral Self-Policing

As the Cultural Revolution progressed, the most effective mechanisms of control no longer required constant external enforcement. The diagnostic logic of wrong thinking was gradually internalized by the population itself. Fear of accusation, isolation, public humiliation, or punishment led individuals to monitor their own thoughts with increasing intensity. Ideological discipline moved inward, becoming a private and continuous activity rather than an episodic response to public campaigns. The revolution no longer needed to search relentlessly for dissent because citizens learned to search themselves first, anticipating judgment before it arrived. Power became anticipatory, operating through expectation rather than constant coercion.

This internalization transformed fear into a permanent condition rather than a response to specific threats. Because the criteria for wrong thinking were fluid, expansive, and often contradictory, certainty was impossible. Individuals could never be fully confident that their beliefs, emotions, or private reactions aligned perfectly with revolutionary expectations. Doubt itself became suspect, not because of its content but because of its existence. This uncertainty produced a continuous state of self-surveillance, in which safety depended on constant vigilance over one’s inner life as well as outward behavior.

Moral self-policing extended beyond belief into affect and memory. People learned to suppress not only critical thoughts but also emotional responses that might signal deviation. Grief for purged colleagues, discomfort with violence, or confusion about abrupt policy shifts all carried risk. The safest emotional posture was visible support. Emotional neutrality could be interpreted as concealment. Individuals trained themselves to experience the correct feelings reflexively, blurring the line between performance and belief and making ideological conformity feel increasingly natural.

This process also reshaped speech and silence in complex ways. Speaking carried danger, but silence did not guarantee safety. What mattered was not the absence of dissenting statements but the presence of correct signals. Individuals rehearsed slogans, participated in denunciations, and performed ideological clarity as a form of self-protection. Speech became ritualized, emptied of spontaneity or inquiry. Words were no longer vehicles of thought or communication. They functioned as shields against suspicion, calibrated displays designed to demonstrate moral health rather than convey meaning.

Fear-driven self-policing fractured trust and intensified isolation. Because ideological sickness was imagined as contagious, individuals learned to distance themselves emotionally from others, even from those they cared about. Confidences became liabilities. Sympathy became dangerous. Shared doubt could become shared guilt. The safest relationship was one governed by mutual performance rather than mutual understanding. Communities survived through coordination of appearances, not shared belief. The result was a society dense with interaction yet hollowed of genuine exchange, where proximity did not produce solidarity and familiarity did not produce trust.

Through internalization, Maoist power achieved its most enduring form. Repression no longer depended solely on violence, denunciation, or surveillance from above. It was sustained through conscience reshaped by fear and habit. Individuals became agents of their own containment, preemptively erasing dissent before it could be articulated. In this way, the pathologization of disagreement completed its work. Authority no longer needed to diagnose openly. Citizens learned to diagnose themselves.

Conclusion: When Power Defines Reality Itself

The Maoist treatment of dissent as moral and cognitive disease represents a culminating form of political insulation, one in which power no longer confronts opposition because opposition is denied intelligibility from the outset. By redefining disagreement as wrong thinking, Maoist authority did not merely suppress alternative views or marginalize critics within an accepted field of debate. It expelled them from reality itself. Critics were not mistaken interlocutors or political adversaries whose claims required refutation. They were understood as corrupted minds, incapable of perception, judgment, or truth. Once this reclassification was complete, argument became unnecessary not because it had failed, but because it had been rendered conceptually impossible. There was nothing left to answer, only something to diagnose.

What makes this system especially enduring is that it did not rely solely on overt violence or centralized repression. It relied on moral certainty presented as rational clarity. By fusing truth with virtue, Maoist ideology transformed loyalty into sanity and skepticism into sickness. This fusion allowed power to present itself not as coercive, but as corrective. Punishment appeared as treatment. Silence appeared as recovery. Authority no longer needed to persuade because persuasion implies uncertainty, and uncertainty was recoded as pathology. The system sustained itself by appearing medically and morally necessary rather than politically contingent.

The deeper consequence was the collapse of shared reality itself. When only one way of thinking is defined as healthy, all others become not merely wrong but unintelligible. Language ceases to function as a medium of exchange and becomes instead a tool of classification and exclusion. History is no longer a contested record but a moral narrative populated by heroes and pathological deviants. Memory becomes dangerous because recollection threatens diagnostic certainty. In such an environment, disagreement cannot perform its civic function because it has been stripped of its status as thought. Power does not win debates. It removes them from the realm in which debate is possible, ensuring that no alternative reality can be articulated or sustained.

The Maoist case offers a broader warning that extends far beyond its historical moment. When regimes claim the authority to define not only truth but mental and moral health, political life is transformed into a system of surveillance and self-erasure. The health of any society depends on its willingness to tolerate disagreement as intelligible, rational, and human, even when it is disruptive. Once power defines reality itself, dissent no longer challenges authority. It disappears.

Bibliography

- Arendt, Hannah. The Origins of Totalitarianism. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Company, 1951.

- Barnes, Amy Jane. “Chinese Propaganda Posters at the British Library.” Visual Resources 36:2 (2020), 124-147.

- Cheek, Timothy. The Intellectual in Modern Chinese History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

- —-. Propaganda and Culture in Mao’s China. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

- Dikötter, Frank. The Cultural Revolution: A People’s History, 1962–1976. New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2016.

- Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage Books, 1975.

- —-. Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason. New York: Vintage Books, 1961.

- Goldman, Merle. “Repression of China’s Public Intellectuals in the Post-Mao Era.” Social Research 76:2 (2009), 659-686.

- MacFarquhar, Roderick. The Cultural Revolution. Vol. 1. New York: Columbia University Press, 1974.

- MacFarquhar, Roderick, and Michael Schoenhals. Mao’s Last Revolution. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006.

- Maiytt, Chrisopher E. “Chinese Propaganda and the People’s Republic in the Twentieth Century.” The Hilltop Review 10:1,15 (2017), 57-63.

- Meisner, Maurice. Mao’s China and After: A History of the People’s Republic. New York: Free Press, 1999.

- Mao Zedong. On Correct Handling of Contradictions Among the People. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1957.

- —-. Quotations from Chairman Mao. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1964.

- Ou, Susan and Heyu Xiong. “Mass Persuasion and the Ideological Origins of the Chinese Cultural Revolution.” Journal of Development Economics 153 (2021), 102732.

- Schram, Stuart. The Thought of Mao Tse-tung. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

- Walder, Andrew G. China Under Mao: A Revolution Derailed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.11.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.