The modern gaze, filtered through lenses, algorithms, and scans, is heir to a much older logic. What has changed is not the desire to know, but the means by which that knowing is achieved.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Flesh as Document, Face as Code

In a world before surveillance cameras, digital fingerprints, and retina scans, the medieval body bore its own scripts of control. Faces were read as if they were texts, scars served as signatures, and clothing could function like a passport or prison stripe. The medieval period, far from being technologically naïve or socially opaque, developed intricate regimes of bodily visibility. What the modern world accomplishes through biometric scans and facial recognition algorithms, medieval institutions pursued through a complex repertoire of branding, apparel regulation, and physiognomic scrutiny. The body was not merely a vessel of identity; it was the terrain upon which law, theology, and custom were inscribed.

These systems, though technologically primitive by today’s standards, were not unsophisticated. The surveillance state had not yet arrived, but its foundational logics – categorization, differentiation, discipline – were already being cultivated. This essay explores the embodied mechanisms by which medieval societies identified and controlled their populations. It focuses especially on those who were labeled deviant, dangerous, or disposable: criminals, heretics, Jews, Muslims, lepers, and the poor. Their bodies were marked not only by law but by culture. In being seen, they were also controlled.

Branding the Deviant: Criminals, Heretics, and the Politics of Pain

Legal Branding and Punitive Visibility

Medieval justice systems frequently turned to the body as both canvas and spectacle. Branding criminals, literally searing their flesh with hot irons, served less as a punishment in itself and more as a tool of permanent classification. These marks functioned as publicly legible signs of transgression, akin to today’s digital criminal records, except they could not be expunged or sealed.1

French and English courts in particular made wide use of this strategy. Thieves might be branded with a “T,” blasphemers with a cross, and repeat offenders with ever more visible disfigurements. The pain inflicted by such procedures was only part of the equation. More important was the way these symbols produced a visible caste of the untrustworthy, a class of bodies that had been judged and now carried their judgment inescapably upon their skin.2

This literal inscription of law onto the flesh gestured to a broader medieval belief in the moral legibility of the body. Branding was not only punitive but epistemological. It made truth visible and mobile. A branded man could be read by anyone (priest, merchant, or magistrate) without the need for testimony or paperwork. His past was written onto his present, and the public itself became a network of enforcement.

Heresy and the Theater of Execution

Heresy, unlike theft or fraud, was often punished not just through fire but with fire. Burning at the stake was the final mark, the obliteration of a body deemed uncontainable. But long before death, heretics were often marked for recognition. The inquisitorial process was not merely interested in rooting out false belief; it sought to map the heretical body as a threat to the Christian corpus.

Even after execution, these bodies could remain symbolically potent. In some cases, corpses were disinterred and posthumously branded, dismembered, or destroyed. Here too, bodily surveillance extended beyond life into the realm of memory and reputation.3 The medieval Christian imagination was preoccupied with the body as a site of revelation. Heretical flesh was inherently suspicious, and ecclesiastical power sought to render it legible through ritualized violence.

Apparel and the Architecture of Visibility

Sumptuary Laws and Regulated Difference

Clothing, unlike the permanent scars of branding, could be changed. Precisely for this reason, medieval authorities sought to regulate it. Sumptuary laws in many medieval cities delineated what certain groups could or could not wear. These statutes were not mere fashion police edicts; they were technologies of visual control.

Jews in thirteenth-century France were required to wear a yellow badge. In Muslim-controlled Iberia, Christians and Jews were similarly marked with specific garments or belts. Prostitutes in various European cities were confined to particular colors, headdresses, or materials. These laws served a dual purpose: they rendered difference visible and they mapped spatial and moral boundaries. One could see who belonged and who did not by reading the streetscape.4

The rationale for such laws was often framed as moral, but the deeper logic was administrative. Visual sorting allowed for easier monitoring, quicker discipline, and public reassurance of hierarchy. Apparel was thus not an expression of the self but a cipher of classification. Like facial recognition today, it was a mechanism that translated individual presence into group identity.

Resistance and the Slippage of Signification

Yet the system was never watertight. The semiotics of clothing could be subverted. Marginalized groups found ways to manipulate or circumvent sartorial restrictions. Some removed identifying badges when outside their neighborhoods; others wore them but altered their position or appearance to reduce stigma. Authorities, aware of these evasions, continually revised laws to plug the gaps.5

The result was a continual semiotic struggle, a war of signs played out on the surface of bodies. The insistence on visibility produced its own counter-economy of concealment and mimicry. This push and pull underscores the reality that surveillance is never fully totalizing. Even in a society that relied on the seen to enforce the known, the marked were never fully watched.

Faces, Forms, and the Proto-Biometric Gaze

Physiognomy and the Myth of the Readable Face

The idea that one’s moral or social identity could be discerned through facial features found deep purchase in medieval Europe. Drawing on ancient sources, particularly Aristotle and Galen, medieval scholars developed a physiognomic tradition that linked facial structure to inner character. The long nose of the noble, the sloped brow of the criminal, the dark eyes of the heretic; these were not simply poetic images but diagnostic tools.6

Manuals circulated that claimed to teach judges and inquisitors how to read faces. Though we would now consider such practices pseudoscientific, in their own context they served a function not unlike that of today’s predictive policing algorithms. Both rest on the premise that identity can be inferred from appearance, that risk can be assessed before the act. In this sense, medieval physiognomy anticipates modern facial surveillance not in method but in mindset.

The Pilgrim and the Stranger

Faces also mattered in the more mundane registers of daily life. Pilgrims often carried tokens of their journey, badges from Canterbury or Compostela, that marked them as sanctified travelers. These too functioned as visible credentials. At the same time, vagabonds and the itinerant poor were often regarded with suspicion. Their unknown faces became causes for concern.

In such cases, communities relied on informal biometric logic. To be known was to be safe; to be unfamiliar was to be potentially dangerous. Identification thus rested less on formal documentation and more on embodied familiarity. This echoes the logic of small-town policing or neighborhood surveillance today, where “not being from around here” can invite interrogation or exclusion.

Documenting the Body: Registers, Rolls, and Bureaucratic Flesh

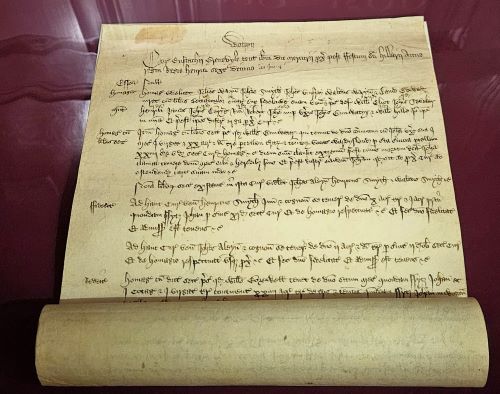

Beyond the visual, medieval societies also began to experiment with written identification. Tax records, tenant rolls, hospital admissions, and poor registers cataloged individuals with increasing specificity. While these documents rarely included physical descriptions, they operated in tandem with visual surveillance to produce a fuller map of populations.

By the thirteenth century, English manorial rolls recorded not only land transfers but also labor obligations and legal penalties, often tied to specific individuals or families. Hospitals such as the Hôtel-Dieu in Paris maintained admission logs, occasionally noting distinguishing marks or conditions. These early archives reflect a growing bureaucratic desire to make bodies knowable across time and space.7

Though less precise than biometric databases, such records served a comparable purpose. They fixed identity in written form, enabled retrieval, and allowed institutions to track subjects over time. Just as contemporary surveillance links faces to databases, medieval documentation linked bodies to parchment.

Conclusion: Seeing the Past in the Present

To read medieval surveillance practices as primitive is to mistake form for function. Though lacking the tools of modern biometric science, medieval regimes developed rich and effective strategies for identification and control. Through branding, apparel, physiognomy, and documentation, they rendered bodies legible to power.

These methods remind us that surveillance has always been a matter not just of technology but of ideology. The modern gaze, filtered through lenses, algorithms, and scans, is heir to a much older logic. What has changed is not the desire to know, but the means by which that knowing is achieved. As we build systems that scan faces in real time, track movement via phones, and cross-reference biometrics with cloud-based identities, we would do well to remember: the face has long been a code, and the body has always been a record.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Esther Cohen, The Modulated Scream: Pain in Late Medieval Culture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010), 145.

- Sara Beam, Laughing Matters: Farce and the Making of Absolutism in France (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007), 84–86.

- Nancy Caciola, Discerning Spirits: Divine and Demonic Possession in the Middle Ages (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2003), 217.

- Ruth Mazo Karras, Unmarriages: Women, Men, and Sexual Unions in the Middle Ages (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012), 101.

- Robert Bartlett, The Natural and the Supernatural in the Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 190.

- Valentin Groebner, Who Are You? Identification, Deception, and Surveillance in Early Modern Europe (New York: Zone Books, 2007), 33–35.

- Michael Clanchy, From Memory to Written Record: England 1066–1307, 3rd ed. (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013), 204–207.

Bibliography

- Bartlett, Robert. The Natural and the Supernatural in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Beam, Sara. Laughing Matters: Farce and the Making of Absolutism in France. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007.

- Caciola, Nancy. Discerning Spirits: Divine and Demonic Possession in the Middle Ages. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2003.

- Clanchy, Michael. From Memory to Written Record: England 1066–1307. 3rd ed. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013.

- Cohen, Esther. The Modulated Scream: Pain in Late Medieval Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010.

- Groebner, Valentin. Who Are You? Identification, Deception, and Surveillance in Early Modern Europe. New York: Zone Books, 2007.

- Karras, Ruth Mazo. Unmarriages: Women, Men, and Sexual Unions in the Middle Ages. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.16.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.