In “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop,” the soaring and chilling speech he delivered the day before his assassination, Martin Luther King Jr. ponders the thought of life in other places and times.

Among other eras in history, he considers the prime of classical Athens, when he could have enjoyed the company of luminaries “around the Parthenon as they discussed the great and eternal issues of reality,” along with “the great heyday of the Roman Empire.”

These considerations of ancient Greece and Rome, in what would be King’s final speech, speak to his close engagement with the Classics throughout his writings.

As one whose courses consider how classical ideas have contributed to public dialogue in the 20th and 21st centuries, I want to address here two particular points of contact with ancient Greece that loom large in King’s thinking and teaching.

The first, King’s advocacy of the Greek concept of agape, transcendent love for others, is critical to his message. The second, his embrace of Socrates as a model of civil disobedience, is revealing of his method.

More than ‘love’

At the core of King’s social teaching lies the necessity for human beings to embrace an all-encompassing love for one another.

But the English word “love,” with its abundance of associations, was too imprecise for what he wanted to convey. In order to express more clearly the type of transcendent love for humanity he was advocating, King turned frequently in his speeches to the ancient Greek he had studied at Crozer Theological Seminary and Boston University.

Building on the work of contemporary theologians – the American Harry Emerson Fosdick (1878-1969), the Swede Anders Nygren (1890-1978) and the German Paul Tillich (1886-1965) – King underscored the distinctions between the Greek words eros (romantic love), philia (the love of personal friendship) and agape (pronounced “a-gáh-pay”).

In his 1957 speech “The Christian Way of Life in Human Relations,” King defines agape as

understanding, creative, redeeming goodwill for all men. It is an overflowing love which seeks nothing in return… It is purely spontaneous, unmotivated, groundless, and creative. It is the love of God operating in the human heart.

This expansive, transcendent understanding of agape is not found in the literature of classical Athens but in the Christian scripture from 400-500 years later, most prominently in Paul’s letters.

In Athenian authors such as Euripides and Plato, the related verb agapao commonly means “to have affection for.” Paul and other early Christian authors elevate agape to something greater.

Its most elaborate and celebrated articulation comes in the first letter to the Corinthians, where Paul writes that agape

does not seek things for itself … [it] sustains all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things…[and] never falls. (1 Cor. 13.5, 7-8).

Just as Paul and others had expanded the understanding of agape to make it all-encompassing, King in his teaching builds upon Paul and brings out agape’s creativity – its capacity to create togetherness and community.

The pestering but important gadfly

King’s medium for enacting his teaching, civil disobedience, was also informed by the Greeks – or, rather, one Greek in particular.

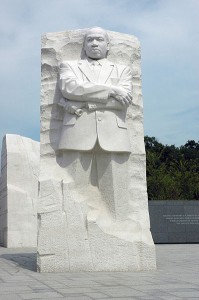

Three times in his 1963 “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” King evokes Socrates (469-399 B.C.), the philosopher who famously made the public streets and squares of Athens his classroom.

King’s letter is addressed to fellow clergymen who had discouraged his practice of nonviolent resistance, on the grounds that it was “unwise and untimely” and could incite civil disturbances.

In making the case for the importance of civil disobedience, King introduces Socrates as one of its early practitioners:

Just as Socrates felt that it was necessary to create a tension in the mind so that individuals could rise from the bondage of myths and half truths to the unfettered realm of creative analysis and objective appraisal, so must we see the need for nonviolent gadflies to create the kind of tension in society that will help men rise from the dark depths of prejudice and racism to the majestic heights of understanding and brotherhood.

The image of a gadfly is drawn from the Apology, a speech attributed to Socrates and related by his student Plato, in which he responds to the charge that he is corrupting Athens’ young citizens with his unconventional and provocative teaching.

Socrates compares the lazy, inert Athenian state to a tired old steed and his own interrogation and urging of Athenian citizens to the buzzing of a gadfly.

Like the fly, he may be annoying, but – Socrates argued – Athenian citizens needed such pestering in order to be stirred into action and improve their lives.

This was precisely King’s point in his letter to opponents of his methods: progress towards social justice can only be achieved through peaceful actions that annoy the status quo, that is, through nonviolent gadflies and the productive tension they create.

Persistent and irritating activism requires courage and significant risk. Socrates and King alike lost their lives for their causes, but both saw peaceful agitation as essential to their identity and work.

Applying the Classics to the 20th century

And so, just as the term agape was able to capture King’s concept of transcendent love in a way no English word could, his evocation of Socrates, the pestering yet productive gadfly, could inform our understanding of the aims of civil disobedience in a uniquely memorable way.

In the speech “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop,” King passes on the fantasy of living in ancient Greece or Rome. Ultimately, he declares his preference for life in the “now” of 1968.

But his lived engagement with the Classics bridges these eras, showing his listeners and readers how classical ideas can speak to us today.

Timothy Joseph

Associate Professor of Classics

College of the Holy Cross