A collaboration between an advertiser and the famous coffee company produced the classic U.S. haggadah.

By Dr. Kerri Steinberg

Department Chair of Liberal Arts and Sciences

Otis College of Art and Design

Introduction

For more than a millennium, the haggadah has been the centerpiece of the Jewish holiday of Passover. The book sets out the ceremony for the Seder meal, when families tell the biblical Exodus story of God delivering the ancient Israelites from slavery in Egypt.

Today, thousands of different haggadahs exist, with prayers, rituals and readings tailored to every type of Seder – from LGBTQ+-affirming to climate-conscious. But for decades, one of the most popular and influential haggadahs in the United States has been a simple version with an unlikely source: the Maxwell House Haggadah, dreamed up in 1932 by the coffee corporation and a Jewish advertising executive.

Its history reflects how Jews modernized and adapted to their new country, while also upholding traditions. But coffee has no ritual ties to Passover. So what explains the Maxwell House Haggadah’s sustained popularity?

Coffee Competition

One explanation is advertising: a field so pervasive and powerful in people’s lives that it becomes almost invisible. As a scholar of American Jewish visual culture and communication, I have researched how marketing can influence Americans’ religious and cultural identities.

The story of the Maxwell House Haggadah begins with the meeting of two marketing masterminds. The first, Joseph Jacobs, grew up on the Lower East Side in New York at the turn of the 20th century, amid a wave of Jewish immigration from Eastern Europe. He went on to establish his advertising company in 1919. The second was Joel Owsley Cheek of the Cheek-Neal Coffee Company, who hailed from the South. Cheek-Neal was then the parent company of Maxwell House coffee, with its famous slogan “good to the last drop.”

Jacobs’ quest to familiarize companies with the buying power of the growing population of Jewish Americans led him to talk with Cheek in 1922 about placing ads for Maxwell House coffee in Jewish journals. There was only one problem: American Jews of Eastern European descent believed that coffee beans, like other legumes, were forbidden for Passover, when certain foods must be avoided, so they drank tea during the weeklong holiday.

Consulting a rabbi from the Lower East Side, who declared that technically coffee beans were like berries and therefore kosher for Passover, Jacobs secured a rabbinical stamp of approval for Maxwell coffee in 1923.

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, when a major grocery chain discounted their own brand of coffee, Maxwell House turned to Jacobs’ firm to help them stay competitive. The Maxwell House Haggadah was born when he suggested distributing a book for free with each purchased can of coffee.

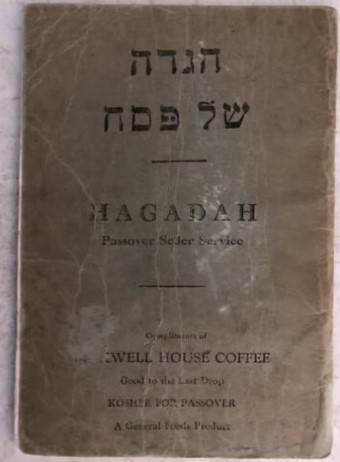

Beyond its appeal as a giveaway, however, the content of the haggadah needed to earn Jewish customers’ trust. The front cover relied upon a classical design of centered text in Hebrew, but also English. Inside, pen and ink illustrations of biblical stories continued the sense of tradition. The pages of the haggadah turned from right to left, as is typical of Hebrew texts.

It worked. According to a market report commissioned by the Joseph Jacobs Organization to guide its marketing efforts, Maxwell House became the coffee of choice for Jewish households around New York City.

Modernizing the Haggadah

The Maxwell House Haggadah remained largely the same through the 1940s and ‘50s, and soon achieved the status of a Passover classic. Yet the 1965 version marked a definitive break with the past. As 1960s culture introduced more minimalist, graphic art, raging against the classicism of the past, the haggadah’s images changed to reflect the times. And though the written text remained largely the same, the addition of English transliterations of blessings and prayers hinted at Americanizing Jews’ loss of Hebrew reading skills.

For the next 30 years, very little changed in the haggadah. But in 2000, it finally received a visual makeover, as seen in an advertisement that year. Stark graphics, popular since the mid-‘60s, were replaced with nostalgic photos depicting an intergenerational family at a Seder. This tender imagery invoked tradition at a time when many Americans had grown more distant from their Jewish communities, prompting concern from Jewish leaders.

In 2009, the haggadah achieved worldwide fame when President Barack Obama used it to conduct his first White House Seder. Shortly after, it underwent a complete overhaul for the 21st century. Maxwell House’s version was now less illustrated and included more written text, like the haggadahs used by more religious Jews. By eliminating antiquated words like “thee” and “thine,” along with gender-specific pronouns for God, the new version felt more relevant for a younger and more secular Jewish population.

And in 2019, when “The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel,” the television show about a mid-century Jewish housewife-turned-comedian, was at its height of popularity, Maxwell House published a special Mrs. Maisel edition of its haggadah. A throwback to the haggadah’s heyday in the late ‘50s, this television tie-in represented yet another marketing effort to retain American Jews’ affection for Maxwell House coffee in a crowded market.

In a sea of thousands of haggadahs, it is Maxwell House’s that has become the de facto representative of American Jewish life. The story of its place within U.S. households points to marketing’s key role in shaping a yearly tradition.

Originally published by The Conversation, 04.14.2022, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution/No derivatives license.