From the ingestion of relic dust and blood-tinged water to the practices of purging and venesection.

By Dr. Emma J. Wells

Historian and Author

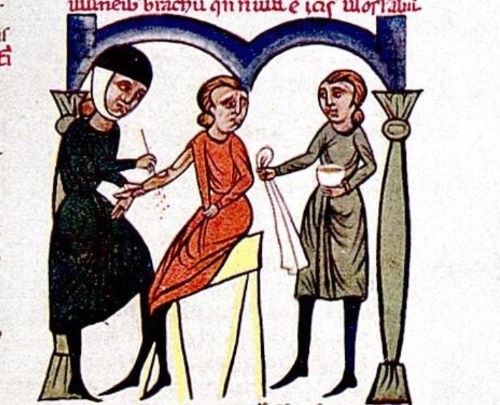

Medieval medical theory in Europe was based around the body having four humours, which, when imbalanced, caused disease. Purging allowed for their ‘rebalancing’, and this was often done to a patient by bleeding them into a bowl or applying leeches to them. Twelfth-century Benedictine abbess Hildegard of Bingen even recommended bloodletting for the cure of leprosy. Monks and priests carried out the practice until the Fourth Lateran Council of 1215, when clergy were prohibited from performing surgical procedures involving bloodshed.

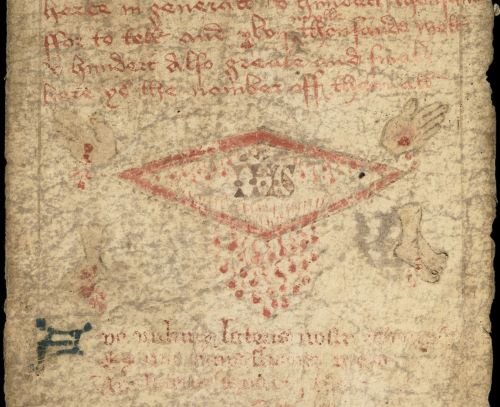

Saintly relics were important curatives throughout the Middle Ages. Bodily remains, associated artefacts, and places linked with saints were thought to work cures and miracles by appealing to the saint for spiritual intervention. Ex-voto offerings – commonly pilgrim badges or other small metal objects – were offered for sale before being blessed at churches housing saints’ shrines and treated as quasi-relics or talismans with thaumaturgical (miraculous) power, allowing a pilgrim to carry the healing essence of a saint home. Relic dust or dirt was also scraped off shrines or the surrounding area of their resting place and mixed with holy water, oil or wine, then ingested as a potential cure.

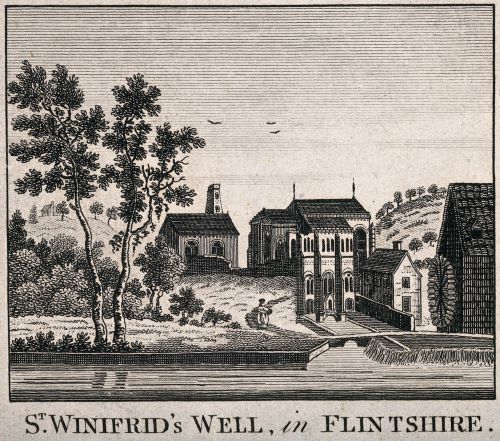

Throughout Latin Christendom, saintly water, such as wells or springs, and even holy water, was reputed to heal the sick via powers derived from the sacrament of baptism and spiritual purification. One of the most notable examples was the ‘water’ of St Thomas or ‘Canterbury water’. Following the murder of Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Becket in December 1170, the monks of Christ Church Priory collected his spilt blood and mixed it with holy water before sealing it in ampullae (tiny metal containers filled with sacred unction). These were then sold as souvenirs at the cathedral. The ‘water’ would be rubbed on the afflicted body parts, consumed, or taken home for future use.

Girdles were frequently used to provide valuable comfort for childbearing women. Associated with miraculous midwives St Margaret and the Virgin Mary, the draping of girdles or belts over pregnant stomachs was commonplace, with many loaned out by monastic houses, particularly during the lying-in phase or to prevent miscarriage. Women would also use their own girdles to ease labour after they had been wrapped around sanctified bells.

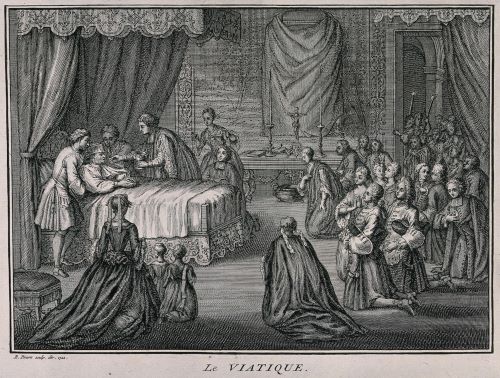

There was little more powerful than faith for the cure of sickness and ailments in the Middle Ages, with many people choosing to place their restorative fate in the hands of God, Christ or the Church. Pope Innocent IV (d. 1254) suggested a priest should be called before a physician. The consecrated Host (the holy sacrament of bread and precious blood or wine) given at Mass was perhaps the most formidable medicine of all. Consuming the body and blood of Christ was thought to combat disease within the body or soul. Women in labour would also receive the sacrament when they were about to give birth.

Uroscopy was commonly used as a diagnostic aid by monastic communities. It began as early as the tenth century, after Isaac Judaeus, an Egyptian-Jewish physician and philosopher, devised guidelines for its implementation. Urine was examined against a chart for clarity, colour, consistency and odour to diagnose diseases or identify which humours were imbalanced. The urine flask became the symbol of medieval physicians. In the Ellesmere manuscript of Chaucer’s ‘Canterbury Tales’, the “Doctour of Physik” uses one while on horseback, and in the marginalia of York Minster’s Pilgrimage Window (c. 1325), monkeys are seen holding urine flasks mimicking the medical profession.

As infections were thought to be transported in vapour form via mists and noxious smells, which could be absorbed through the pores or inhaled, monastic infirmaries used plants that produced ‘good’ smells, such as rose, violet and mint. These were given through the nose to affect the heart and mind or rebalance the humours. The Syon Abbey Herbal (c. 1517) listed over 700 herbal plants and half as many remedies, while excavations at the Augustinian St Mary Spital in Bishopsgate, London found jars with residues of hemp, opium poppy, rose, cedar and pine.

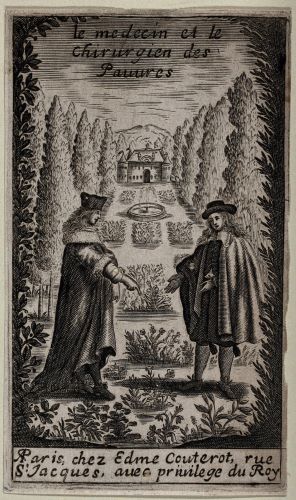

Surgical intervention was rare in the medieval monastic infirmary, but monks would attempt to manage trauma such as lacerations, dislocations, amputations, trephination (also known as trepanning or burr-holing) and fractures. Throughout Britain, evidence survives for just five cases of trephination and two amputations at medieval infirmaries. These types of operations were performed by more experienced laymen, often bonesetters or barber-surgeons, but both the surgeon and patient would receive the sacrament of confession by the brothers prior to the operation.

Originally published by Wellcome Library, 12.13.2022, under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.