Coins and seals held differing functions in medieval society.

By Dr. Jitske Jasperse

Professur für Bildkulturen des Mittelalters

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin

Introduction

Over the past two decades, medieval women as owners of seals and issuers of coinage have attracted a good deal of attention, specifically focusing on the relationship between the visual elements and the communication of elite status and power.1 The carefully considered combination of text and image impressed into metal demonstrated the power of the most elite members of society through the restricted capacity to emit coinage; at the same time, it allowed them to promote their specific social identity. For seals, a similar sophisticated visual strategy was used, which permitted a broader range of the upper echelon to communicate messages of authority, identity, and legitimacy, if not to such a wide audience as that reached by coins.2 Taking the coins and seals of Matilda and other women as our material evidence, this essay investigates the visual constructions of status, gender, and dynastic identity. In doing so, these “miniature yet mighty expressions of medieval art” help to understand how power was displayed, experienced, and exercised by women.3

Coins and seals, of course, held differing functions in medieval society, even as modern items such as security seals provide uses today. Coins were currency used in transactions, and the issuing of coinage offered a source of income to authorities through renovationes monetae (reminting of the whole of the coinage at regular intervals).4 Seals, in turn, were appended to documents to authenticate them, showing that their content was genuine while also indicating the authority of the issuer.5 Moreover, their quantity and distribution varied. Whereas coins would be mass pro‐duced and were mostly dispersed regionally, seals were made in smaller quantities and their final destination in ecclesiastical or secular archives depended much on the content of the charter and the parties that sealed the deal. Furthermore, coins would often be melted down to reuse the metal for issuing new coins. Wax seals, on the other hand, were meant to be preserved, and to this end the fragile objects received protective wrappings or bags, in an—often unsuccessful—attempt to ensure their survival.6 Notwithstanding these differences, both coins and seals stemmed from an engraved metal die—often a silver alloy—that transformed metal into coin and wax into seal. As Brigitte Bedos-Rezak has argued in her ground-breaking research on medieval seals, the act of imprinting also transformed the meaning of the material object. The moment the sealer impressed the die, wax was no longer just beeswax but rather his or her person‐hood was imprinted as well. The seal truly embodied its owner: it made present the sealing authorities who were absent.7 Asimilar argument can be made for coins.

Mundane matters complicate the study of these diminutive objects. The fact that many seals are no longer appended to the original charters hampers a more nuanced appreciation of the contexts in which they were used, as well as how often they were attached to documents and thus the possible audiences who had access to the imagery. Nonetheless, seals were meant to be seen; the imitation and appropriation of seals’ iconographic motifs is proof of their visibility.8 In turn, our understanding of coinage is hindered by the fact, noted above, that coins were often melted down.9 If specimens were discovered individually, indicating that the owner randomly lost a coin, rather than in a hoard (a collection buried at a certain moment for a specific reason), it is much more difficult to establish the time of issue and how widely a particular coin type was used. Nonetheless, it is evident that these small objects held great social value to their medieval users and therefore merit careful attention for the material evidence they offer.

To Wield the Sceptre: Coins and Co-Rule

At a construction site in the vicinity of the Monastery of St. Aegidius in Brunswick, 208 bracteates were unearthed in 1756, of which all but one had been issued by Henry the Lion.10 Exactly why these coins were amassed remains unknown, but given that they were minted under the auspices of the duke, it has been suggested that they were buried during his lifetime, prior to 1195.11 Among these silver coins were sixty-three bearing a representation of Duke Henry and his wife Matilda, one of the many coin types the duke issued in Brunswick (Figure 1).12 Matilda (on the viewer’s left) and Henry the Lion are depicted in bust atop an architectural structure, which either represents the town of Brunswick or the ducal couple’s Burg.13 According to the fashion of their time, each wears a chemise with tight-fitted sleeves under a bliaut with wider sleeves that drape loosely as they hold aloft sceptres. The duchess’s hair is covered by a veil and coronet, while the duke’s is parted down the middle, with curls falling over his ears. Here, like on all bracteates he issued, Henry’s lion is present, referring to the duke’s soubriquet specifically which he carried from 1156 onward.14 To bolster his roaring image, the duke had an enormous bronze lion set up in front of his Burg and as a consequence the lion became an even stronger visual sign of Henry’s name and ducal identity.15 The legend on the coin type under discussion here includes the name DUX HEINRICS O LEO A, adding a corroborating text to the visual lion as the issuing authority.16 Of the mentioned elements two are unique on the duke’s coinage:the inclusion of Matilda, and the fact that she is holding a sceptre.

Unlike coins that bear text and/or imagery on both sides, bracteates are single-sided. Rather than interpreting this bracteate as an object meant to commemorate the 1168 wedding of Henry and Matilda, I argue that the presence of the sceptre in Matilda’s hand invites a very different reading.17 Matilda’s first four years in her new home had not been marked by an active assertion of her authority, but this changed when Henry departed on crusade in January 1172, leaving his wife, now older and firmly established as duchess, equipped to hold real authority in his stead if necessary. In my reading of the imagery, it was this occasion that motivated the creation and distribution of a new bracteate featuring Matilda wielding a sceptre as a consors regni or co‐ruler with her husband.18 As such, the image presented on this coin features the new power-sharing arrangement necessitated by Henry’s crusading activity.19

An interpretation of Henry and Matilda’s coin type as a means to express co-rule, however, is not without its difficulties. First, there is the absence of written record on the issuing of this coin type (or other types, for that matter). Second, coins depicting elite husbands and wives have not been studied in great depth, even though twelve other couples in the Holy Roman Empire were represented on coins.20 Moreover, changes in the iconography found on coins did not necessarily relate to shifts in political thinking, but were in many cases the result of the renewal of coinage at regular intervals. One might even contend that Matilda’s presence on the coin, instead of indicating co-rule, merely underscored Henry’s enhanced status following their marriage, making her into a mere attribute of the duke’s rule. However, had this indeed been the case, one would expect to find Matilda on other coin types as well to fulfil the same role. Nonetheless, medievalists have long acknowledged the importance of coins as a medium for the public commemoration of specific events or of changing political circumstances.21 Finally, as we will see, even when there are written sources, women’s agency and power—like that of men—are never clear cut, especially in narrative sources where authors and patrons have their own agendas.22 In their gesta and chronicles, monks and clerks are not always explicit about women’s participation in gatherings where the performance of power was crucial (e.g. meals, weddings, court meetings). Moreover, the interactions between people often went undocumented, as did the rituals that were part of courtly encounters.

While the familiar royal motif of the joint depiction of husband and wife was copied on some coins issued by the upper nobility, none of the known aristocratic examples shows women bearing sceptres. Henry and Matilda’s appropriation of the imperial design can be understood as an expression of their royal self-awareness, which they also displayed in their gospel book. As the descendants of Emperor Lothar and Empress Richenza on his side, and of King Henry II, and Empress Matilda on hers, Henry and Matilda made sure to emphasize their lineage. An impressive ancestry buttressed their status and offered the framework for the rightful exercise of power. Here, the sceptre would not have been a necessary attribute for Matilda, yet that she holds this insignia is designed to be clearly visible. Like her husband, she raises aloft a fairly long rod topped with a fleur-de-lis. In the hands of a male ruler, the sceptre habitually has been regarded as an attribute of authority and an expression of power.23 Why then, when the same insignia is shown in the hand of a woman, should it not be interpreted the same way?

The earliest visual evidence for women in the Holy Roman Empire to be portrayed with sceptres is related to Queen Cunigunde (r. 1002–1024, d.1033)and Empress Agnes (r. 1043–1077). Their sceptres reflect their active participation in the political and religious affairs of their husbands, via interventions and regency.24 By the 1050s, German kings, emperors, and their consorts are no longer regularly found together in liturgical manuscripts.25 Instead, coins became the primary form of communication of the queen’s image and presence in tandem with that of her husband.

After their marriage, Frederick Barbarossa to Adelaide of Vohburg (1128–d. after 1187)appear together on coins, enthroned and richly dressed, with their heads turned towards each other (Figure 2). As a sign of their rule, each wears a crown. Frederick holds a lance in his left hand and a long rod topped by a cross in his right; Adelaide has an open book in her right hand and a small flowering sceptre in her left.26 The book may symbolize a woman’s religious virtue, as it does on seals of abbesses and in the hands of the Virgin Mary.27 Because the legend identifies Frederick as king, this coin type is likely to have been issued after his coronation on March 9, 1152 and before March 1153, when his marriage to Adelaide was annulled. Adelaide is not referred to as consors regni on the coin, though that does not necessarily mean that her presence was passive. However, the limits of her intervention in matters of state is suggested by her absence from the documentary evidence. Adelaide appeared in only one charter in the course of her short reign, which suggests that her radius of action was limited.28

Not so for Beatrice (1145–1184), Frederick’s second wife, whom he married in June 1156 at Würzburg. From that time she used the title dei gratia Romanorum imperatrix augusta, although she was not formally crowned empress until July 1167.29 Beatrice is depicted together with her husband on bracteates issued some time between 1156 and 1184.30 On one, Beatrice is shown on Frederick’s right, in a manner similar to the depic‐tion of Adelaide (Figure 3). She holds a short rod crowned by a lily of the same type decorating Matilda’s sceptre. Both emperor and empress are portrayed half-length, wearing crowns and similar attire. Frederick holds a rod surmounted by a cross in his right hand, a reference to the Holy Roman Empire. In compositional terms, on both of Frederick’s bracteates the rod separates the king from his wife. Despite the paucity of contemporary sources referring to Beatrice, Amalie Fößel has been able to determine that Beatrice frequently travelled with her husband and was actively involved in the affairs of the county of Burgundy, and that she also intervened on behalf of monasteries, churches and bishops, as noted in Frederick’s charters.31 The royal couple’s mutual activities suggest that the notion of co-rule was deliberately communicated through their coinage as well.

The cases of Adelaide and Beatrice show that a single reading of this coin type as reflecting and communicating co-rule is problematic. However, in the case of Henry the Lion’s coin, it is significant that the duke seems to have followed the same course of action with his first wife, Clementia—whom he married in 1147 and separated from in 1162—as he would later do with Matilda. The ducal couple is depicted on a bracteate of which two specimens are known, one found at Duderstadt (Lower Saxony) and another at Bourg-Saint-Christophe (France, département Ain) (Figure 4).32 They are portrayed in profile on top of two arches; beneath the arches, a lion is shown facing right. There is no legend on the coin to identify the issuing authority, but the presence of the lion makes it perfectly clear that this type is related to Brunswick and Henry the Lion. Due to its schematic, and less detailed style, this coin is dated around 1150. Henry’s reason for issuing this coin type can be understood from his political activities at this time. In 1151, Henry left Lüneburg in order to claim Bavaria. The twelfth-century chronicler Helmold of Bosau, who knew Henry well, writes that in preparation for this military campaign the duke assigned Count Adolf of Holstein (d. 1164)to guard over his Slavic lands and the territories north of the River Elbe. Henry’s wife, called the “duchess, lady Clementia,” remained in Lüneburg, with Count Adolf, who was in charge and dutifully served her.33 According to Helmold, Adolf held custody over the lands, yet it was to the duchess that the Abodrite ruler Niklot turned in 1151 for help in enforcing the payment of taxes to him by other Slavic tribes.34 Clearly Clementia was considered the highest authority in the absence of the duke and therefore the appropriate person to address. And indeed, she took action, sending Count Adolf along with Niklot to support him. In 1154 the duchess acted again in Henry’s absence. That year, Clementia sent Gerold, her husband’s chaplain, to Oldenburg to occupy the episcopal see upon the death of the pre‐vious bishop.35 A decision of this type is clear evidence of active rulership on the part of the duchess.

The exact protocol and manner of appointment by which Clementia and other noble‐women came to rule during their husbands’ absence remains unclear. In some sources husbands explicitly appointed their wives as regents. For example, before departing on crusade in 1095, Count Robert II of Flanders (r. 1093–1111) referred to Clemence of Burgundy (r. 1096–1133) in a letter as:“My wife named Clemence, who was put in charge of all my land and with it all my rights during my absence.”36 Robert had stated explicitly that Clemence should rule over his territories in his stead. Similarly, a letter by Count Stephen of Blois together with a reference by Orderic Vitalis attest that Stephen’s wife Adela held full comital authority during his stay in the Holy Land between 1097 and 1100.37 Clearly, the moment women ruled in place of the men offered an excellent opportunity to communicate joint rulership. Adela did so by employing her husband’s seal on charters she signed, while Clementia and Henry issued coins as visual reminders of their joint rule, which was meant to underscore unity and ducal stability.38 Henry’s absence warranted such a message since opponents were always eager to impinge on his authority and territory. To the duke, transferring and sharing authority with a woman was a strategy with which he would have been familiar from his youth. After his father Henry the Proud died, his mother Gertrud and maternal grandmother Richenza acted as regents until the young duke had come of age.39

Just as with his first consort, the iconography of the later bracteate on which Henry is represented with Matilda should be understood within the context of the transfer of ducal authority from Henry to his wife. Matilda also would have been well acquainted with this form of rulership since she had witnessed how her mother ruled as a regent when Henry II was otherwise engaged and how Eleanor frequently travelled to act as her husband’s deputy in Anjou and Maine.40 What is more, on many occasions Eleanor even took Matilda and her other daughters with her, and so they would have learned at first hand the strategies employed by their mother as Eleanor exercised authority across different territories.41 The bracteate would have constituted a suitable means to communicate transfer of authority on the eve of Henry’s departure to the Holy Land in January 1172. Although we do not have such a direct, contemporary statement as that noted above by Robert of Flanders to his wife Clemence, the event was narrated ca. 1210 by Arnold of Lübeck in his Chronica Slavorum:

So he [Henry] managed his affairs, thinking about leaving for Jerusalem, and put his land under the tutelage of Archbishop Wichmann of Magdeburg, attested by the aristocrats of his land who travelled with him. […] And none of the prominent men stayed behind, except Eckbert of Wolfenbüttel, who was appointed by the duke as head of his whole household, yet who was mainly assigned in the service of Lady Duchess Matilda. […] She remained at Brunswick during the time the duke was on pilgrimage, as she was pregnant and she gave birth to a daughter Richenza. […] Henry of Lüneburg and the aforementioned Eckbert served her, because they were faithful and honoured the duke’s household.42

Why does Arnold appear to downplay Matilda’s role in this passage concerned with Henry the Lion? It is possible that the author wanted to foreground that Henry was married, or that he left behind a well-organized duchy, or perhaps that an heir to the duchy was on its way. Matilda’s body is framed as maternal rather than as a ruler, but this does not mean that the part of mother is the only one she had to play. Wichmann’s tutelage should not be taken at face value, since the nature of his duties as regent as well as his relationship with Henry are not at all clear. Even if we were to accept Arnold’s remark that the bishop gained temporary control over Saxony, this would not exclude Matilda’s involvement in such affairs. The support the duchess received from Eckbert of Wolfenbüttel and Henry of Lüneburg was likely to have been similar to what they would have offered the duke. While this reference to Matilda suggests that she played an important role during her husband’s absence, in his chronicle Arnold clearly was interested in presenting the duke in the most favourable light by emphasizing his power (which included force and violence), honour, and piety. Of course, Henry the Lion would have applauded this kind of image-building, but the narrative would always be that of Arnold, abbot of the monastery of St. John at Lübeck. By contrast, the image on the coin was sanctioned by the duke himself at a specific moment in time, that is, before he journeyed to the Holy Land and it enabled him to inform all that the authority within the duchy, centred on Brunswick as its most important place of residence, was and would remain in ducal hands even when the duke himself was temporarily away. If the dearth of contemporary written documents make it unclear how exactly Matilda exercised such authority, the coin type discussed here makes it more than evident that her presence at Brunswick mattered greatly. As such, this artefact is an important witness to the image the ducal couple wished to project.

In order to understand the communicative impact of this coin, we must return to where we started:the location where the hoard of coins was found. The specimens with the representation of Duke Henry and Duchess Matilda were discovered near the Aegidius monastery, and it is safe to assume that more coins than the sixty-three found there were originally issued. Like Henry the Lion’s other coin types, it is likely to have been used in his northern Saxon lands located between the rivers Elbe and Weser, where the coins would have been a valid means of payment.43 Rather than assuming that coins were targeted at the widest possible viewership, the regional dispersion indicates that messages were aimed at an audience that was closest to the ducal house.44 Henry and Matilda followed an established pattern; precisely the elite people who were connected to the ducal house and were in the position to use money needed to understand that even though the duke was away, the natural order of things was preserved.

Making Impressions: The Sway of Seals

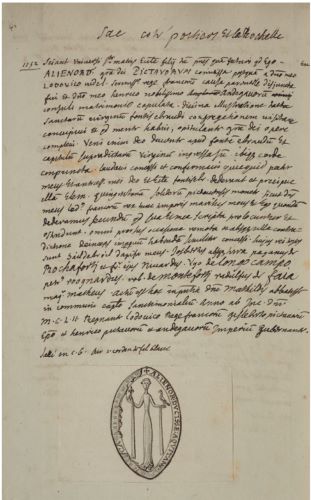

Unlike Henry the Lion, Matilda is not known to have impressed her image onto wax. This fits the pattern for twelfth-century Germany, where fewer noblewomen sealed documents than in England and France.45 If Matilda made use of Henry’s seal, no document of this type has survived. An analysis of personal seals in the hands of Matilda’s mother and sisters shows that these women followed an established iconography as they constructed and subsequently impressed their gendered and dynastic identity through insignia, dress, and legend. Before turning to Matilda’s half-sisters Marie and Alix, I will briefly discuss their mother’s seals, which may have served as a source of inspiration to her daughters. According to Elizabeth Brown, three different seals of Eleanor are known, although Kathleen Nolan suggested that the first and second seal result from the same matrix but were in different states of preservation.46

After her marriage with King Louis VII of France was annulled in 1152, Eleanor issued a single-sided ogival seal as duchess of the Aquitainians, as is evidenced by the legible part of the titulus (Figure 5).47 The duchess is represented standing frontally, wearing a tight-fitted long dress with long hanging sleeve cuffs reaching almost to her ankles. In her right hand she holds a fleur-de-lis, while a dove is perched on her left.48 Several authors have read the fleur-de-lis on Eleanor’s seal as a reference to the Tree of Jesse, which was connected to motherhood and fertility in the Middle Ages and therefore a fitting emblem to signify dynastic continuity.49 There is something to be said for this interpretation because insignia referred to specific duties, signifying the defence of land and people, and the sceptre designated the exercise of lordship, including justice. Seen in this light, it was among women’s jobs to provide an heir, and the fleur-de-lis may have signalled this.

Another drawing made for Roger Gaignières shows what Eleanor’s two-sided seal as queen of the English looked like, completing the details of surviving examples (Figure 6 and Figure 7 a–b).50 This seal, which was of larger dimensions than the earlier one, needed to be turned to view both sides. Obverse and reverse present an identical image of the queen dressed in a tight-fitting long bliaut, a mantle covering both shoulders, and a barbette topped by a crown of three points fleury. Rather than an identifiable fleur-de-lis, Eleanor holds a branch of which the top petals have the shape of a fleur-de-lis. In her left hand the bird motif has been replaced by an orb surmounted by a cross topped with a dove. Elizabeth Brown has argued that the dove symbolized the wisdom and intelligence of Christian rulers; in the representational context of seals this interpretation is convincing.51 Brown adds that this symbol of authority was appropriated from the seals of English monarchs, such as Edward the Confessor, Henry I, Stephen, and Henry II, showing Eleanor’s ambition to possess as her own the English sigillography that expressed power and authority.52 Even though a visual hierarchy between front and back is absent, Gagnières’ drawing suggests that the obverse was meant to be the side that contains the legend + ALIENOR DEI GRATIA REGINE ANGLORVM DVCISSE NORMAN’ (Eleanor, by the grace of God, queen of the English, duchess of the Normans), while the reverse legend designates her duchess of Aquitaine and countess of Anjou. Did Eleanor’s daughters follow their mother’s seal designs?

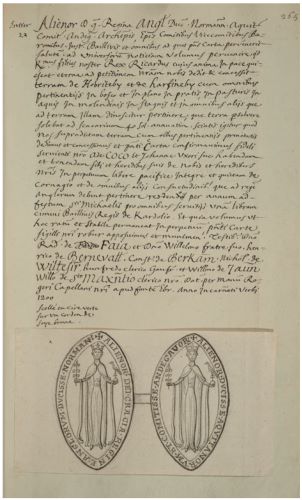

Marie of Champagne (r. 1166–1198), eldest daughter of Eleanor of Aquitaine and King Louis VII, held two single-sided ogival seals which she used from 1166, when she married Count Henry the Liberal (r. 1152–1181), until her death in 1198. Although the seals, of which five wax impressions survive, stem from two different matrices (the second is somewhat larger and its design less refined), their iconography and legend are identical.53 On a reddish wax seal attached to a document issued in 1166, Marie is represented wearing an elegant bliaut with long sleeves and a mantle that is draped over her shoulders (Figure 8). As such she follows the fashion of her mother and other noblewomen of her time. Like Eleanor on her first seal, Marie holds a bird in her left hand, while in her right a fleur-de-lis on a short rod is visible. In the seal’s legend she ties herself to her husband through whom she was able to claim her title and power as countess of Troyes. However, the first connection she establishes is with her father:+ SIGILL[VM]. MARIE.REG[IS]. FRANCOR[VM]. FILIE.TRECENS[IVM]. COMITISE (Seal of Marie, daughter of the king of the Franks, countess of Troyes).54 That she did so on both seals indicates that the importance of the repeated confirmation of blood ties between Marie and her father, even long after Louis’s death in 1180.

The same message appears to have been communicated on the seal of Alix of Blois (r. 1164–ca. 1199), the second daughter of Eleanor and Louis VII, and wife of Count Thibaud V of Blois (r. 1152–1191), who was the brother of Henry the Liberal. Combining the fragments of her two known seal impressions reveals that the countess stood in a three-quarters contrapposto pose and was dressed in a long, elegant bliaut with a fur‐lined mantle covering her shoulders (Figure 9 and Figure 10). Her hair is covered by a veil and wimple. Like her mother, Alix carries a branch topped with a fleur-de-lis in her right hand, while a bird is perched on her left hand. The legend reads:[SIGI]LLVM [… FR]ANC [COMITI]SSE B[LESENSIS].55 The name “Adelicia” is now missing, but would have been part of the original inscription. The presence of “franc”—“francie” or “francorum”—makes no sense without the word “filie.” Indeed, a drawing accompanying a transcription of a charter issued by Alix in 1199, as recorded by Gaignières, testifies that the legend contained:FILIE LODO[…] FRANC.56 The complete legend would thus have been: “Seal of Alix, daughter of Louis, king of the Franks, countess of Blois.”

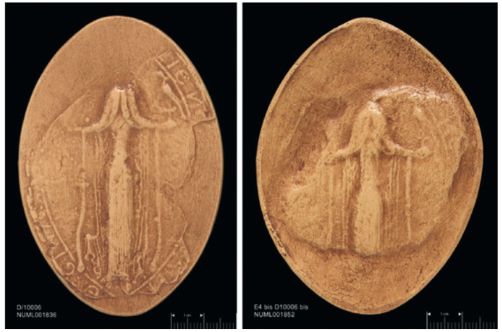

The filia reference occurred with some frequency on elite women’s seals, as is also testified to by the seal matrices of Marie’s and Alix’s half-sister Joanna.57 The silver matrices, made in 1196 when she was married to the count of Toulouse, reveal two delicately carved figural representations in low relief (Figure 11 a–b).58 On the obverse, Joanna is shown standing. She appears as an elegantly dressed queen wearing a crown of four points fleury and holding her mantle cord with her left hand while prominently displaying a fleur-de-lis in her right. Her long bliaut is cinched by a narrow belt decorated with tiny dots that are meant to evoke precious stones. Her mantle falls open, showing its ermine lining. The representations of costly fur and gemstones under‐score Joanna’s high standing. The legend, + S REGINE IOHE FILIE QVONDAM H REGIS ANGLORUM (Seal of Queen Joanna, daughter of Henry, the former king of the English), is crucial for a better understanding of this woman’s position. Her royal title could refer to Joanna’s former status as queen of Sicily, to her royal status through her father, or both. The former option seems probable since in her testament of 1199, she would make a donation to Fontevraud to commemorate the anniversaries of the long-dead “king of Sicily” and herself, indicating that she still connected herself to her first husband. Moreover, it was not uncommon for widowed women to continue using their deceased husband’s titles: Joanna’s grandmother Matilda still called herself empress, for example, long after she had returned to England following the death of her first husband.59 Yet it is also possible that the reference to Joanna’s regal status refers to her royal birth, especially if we consider that she explicitly connects herself to her deceased father in the legend on one side of the seal.

The reverse of Joanna’s seal matrix tells a different story, both in image and word. Here the legend proclaims her current connections, defining her status as duchess of Narbonne, countess of Toulouse and marchioness of Provence (+ S IOHE DVCISSE NARB COMTISSE THOL MARCHISIE PROV). Enthroned yet uncrowned, Joanna wears a long dress draped in thick folds, and she holds her mantle cord with her right hand (which would become the left, once impressed on wax) while proffering an impressive cross with the other. The equal-armed cross explicitly connects the princess to her Toulousan marital family, thereby underlining her second marriage. An early depiction of this Greek cross with three balls decorating the outer ends of each bar can be found on the lead bullae of her father-in-law Count Raymond V (d. 1194), who also employed a Latin cross decorated with similar balls on the equestrian side of his wax seals. The use of this Latin cross was continued by Joanna’s husband Raymond VI (d. 1222) and her son Raymond VII (d. 1249), suggesting that this Toulousan (or Occitan) cross was considered a family emblem.60 Her folding throne, though uncommon for women, resembles the obverse of the round seal of Joanna’s mother-in-law Constance, who is also depicted bare-headed and seated, albeit on a rectangular chair-throne.61

On Constance’s seal, she holds in front of her chest a Toulousan cross of different size and style from Joanna’s, and with her left hand displays a lily-topped orb.62 This side of Constance’s two-sided seal affirms her royalty, as daughter of Louis VI of France and sister of Louis VII, and its round shape was probably inspired by the latter’s seal, which also served as a model for that of Count Raymond V, Constance’s spouse.63 Joanna’s husband Raymond VI continued this royal symbolism on his seal, having himself depicted on a throne, holding a sword and flanked by the sun and moon; the latter are also present on his parents’ seals, but absent from Joanna’s.64 Yet, where her husband—following both his father and his mother—chose equestrian imagery for the reverse of his lead and wax seals, Joanna’s “royal side” represented her as a standing queen. It was this side of her seal that personalized it by connecting the queen to her natal family; it thus showed her to be more than just the wife of a count, who may have been influential but was of lower birth than Joanna as daughter of a king. The matrices of Joanna’s seal do not only reflect political considerations of the Plantagenets and Raimondins; they are also rare and precious sources representing key moments in the her life:her royal lineage, her marriages, and perhaps even her motherhood, if we accept that the fleur-de-lis refers to this.65 Joanna’s royal lineage through her father was also emphasized in 1208 by Raymond VI, by then long a widower, when he issued a charter in which he represented their son as “R. filium nostrum, quem habimus de regina Johanna, filia Henricis Regis quondam Angliae” (R[aymond VII] our son, whom we have with Queen Joanna, daughter of Henry former king of the English).66

There is no doubt that Joanna’s matrices show a clear dynastic awareness in both word and image. But were wax seals ever made from them? Her matrices were found in the late nineteenth century during excavations at the ruins of the former Cistercian monastery of Grandselve (dép. Tarn-et-Garonne), about fifty kilometres north-east of Toulouse. How her seal matrix, and that of her son Raymond VII, ended up at Grandselve is an open question.67 The counts of Toulouse, especially it seems Raymond V (r. 1148–1194), had a long-lasting relationship with this Cistercian monastery, which had been founded in 1114.68 The monastery also sought aid from the English King Henry I, although the first evidence that support might have been given only appears in the 1170s with Richard the Lionheart, who granted it protection and trading privileges.69 Joanna could have been familiar with the monastery of Grandselve through both her natal and marital families. Further, she might have been involved in some of her husband’s dealings with the monastery, especially as they concerned salt from Agen, belonging to her dowry land.70 A 1261 inspeximus by Vincent, archbishop of Tours, confirmed that Joanna, “formerly queen of Sicily, now duchess of the March, countess of Toulouse, marchioness of Provence,” had allocated rent from her saltpans at Agen for their kitchen of Fontevraud.71 Perhaps Joanna employed her seal on this occasion. The traces of white and green wax found on the matrices by Abbot Pottier indicate that they were indeed used.72 Yet it also possible that she and her son followed the kingly practice of gifting seals to a monastery on their deathbeds with the expectation that the matrices would be melted down to be reused for church furnishings.73 Another possibility has been offered by Brigitte Bedos-Rezak, who suggested that the matrices could have been presented by Raymond in order to compensate for the damage the abbey had suffered during the war with the French king.74 Its abbot, Elie Guarin (d. ca. 1232), persuaded Raymond to sign the treaty of Meaux-Paris (1229), in which it was stipulated that the count had to pay 1,000 marks to the abbey.75 Payment in kind rather than in coin was not unheard of. In the cartulary of St. Loup at Troyes, for example, the abbot noted that Marie of Champagne offered her signet ring as compensation for an infraction against the abbey.76

How often Joanna’s sister Leonor, who lived in Iberia but remained well connected to the Occitan speaking world, made use of her seal is equally difficult to establish. Leonor’s pointed oval two-sided wax seal is only known through a charter from April 1179 (kept in Toledo) to which the sole surviving example is still appended.77 However, a recently discovered charter issued by Leonor in November 1179 (originally kept at the Hospital del Rey in Burgos) in all likelihood had a wax seal attached to it, as is suggested by the fold at the bottom of the parchment (plica) meant to strengthen the parchment so that a seal could be appended.78 So there were at least two occasions on which the queen’s seal was added to documents that were issued in her name. While the queen is mentioned in the majority of her husband Alfonso VIII’s charters,79 only the two charters from 1179 state that the queen validated them with her own hand, which can be read as a reference to the wax seal and/or to the signo rodado, which is the round seal drawn onto both charters.80 In the sealed charter at Toledo, Leonor confirms and extends the endowment of the altar of St. Thomas Becket in Toledo Cathedral, which had been founded by Count Nuño Pérez de Lara (Alfonso’s former tutor) and his wife Teresa. The queen’s confirmation contributed to the spread of the Becket cult, and this document clearly testifies to Leonor’s involvement:in its intitulatio her name is given, unusually, before that of her husband.81 Her primary role is further supported by the eschatocol, which, together with Leonor’s signo rodado, signals that the queen was the driving force behind this dona‐tion.82 The slits in the Toledo charter offer evidence that only the yellow-brown wax seal of Leonor, and not that of her husband, was appended on a leather strip. Although reproductions of her seal imply that it was impressed on one side only, both sides bear slightly different depictions of the queen.83 Leonor’s seal also is the earliest surviving specimen connected to a Castilian or Leonese queen.84 This means that Leonor had no female model from her marital family available to copy.

On the obverse of the seal, Leonor wears a slender-fitting bliaut, a long mantle, and a crown on her veiled head; she is depicted with a bird perched on her left hand in exactly the same fashion as her mother on two surviving early specimens (Figure 12 a–b). It is not clear what the queen is doing with her right hand, possibly pointing her index finger in a gesture of command. The size of Leonor’s seal, the depiction of the bird, and the almost identical images on both sides suggest that the Castilian queen modelled her seal after those of her mother. Unfortunately, it is now impossible to read the legend on either side of her seal, but in Julio González’s 1960 edition of the charters of Alfonso VIII, he provided a drawing of the obverse with the legend + SIGILLVM:REGINE:ALIENOR:.85

At first sight the representation of Leonor on the reverse is the same as the obverse, yet her standing pose and gestures have shifted slightly so the mantle is draped differently, making it flow, and here the crown with its three points fleury resembles that of her mother. By analogy with contemporary seals of other elite women it seems that she holds her mantle cord with her left hand, a sign of high rank. The object in her right hand is again difficult to interpret; it could be a flower, but also a plant or small tree.86 We already saw that Leonor’s sister Joanna employed the fleur-de-lis on her seal, and so did their half-sister Marie of Champagne. In all these cases the flower indicated high status, authority and, at times, power, and it is easy to imagine that Leonor incorporated it in her seal in full knowledge of its use by Anglo-Norman and French queens and aristocratic women. Based in part on the seals of Joanna and Marie de Champagne, it is tempting to speculate that the titulus on Leonor’seal would have included the term filia regis, as did the inscription on two liturgical textiles. There certainly is sufficient space along the edges available for such an inscription, and Leonor’s name could have been abbreviated like that of her sister. However, it is also possible that the legend on Leonor’s seal mirrors that of her husband, thus reading + SIGILLVM:REGINE:ALIENOR (Seal of Queen Leonor) on the obverse and REGINA:CASTELLE (Queen of Castile) on the reverse.87 While the complete inscriptions on her two-sided seal are uncertain, the shape, iconography, and size certainly give the impression that Leonor consciously referred to the seals of her mother to underscore her roots. This is confirmed by the absence of the castle that her husband employed on his two-sided lead seal from ca. 1175 onwards.

Insignia, dress, and inscriptions were crucial elements to coins’ and seals’ communicative powers. They could demonstrate an elite woman’s royal descent, as well as her position as a royal and/or noble consort, widow, regent, and co-ruler. As such, these small artefacts allowed women like Eleanor of Aquitaine and her daughters to display and assert the multiple experiences that shaped their identities. This self-fashioning was equally important for those connected to them by family ties (natal or marital), as well as to their peers. In this respect, Elizabeth Brown’s observation that “as is true of all mute objects, the seals’ significance is not so easy to access” may be a bit too pessimistic.88 Imitating the iconography employed by Eleanor and referring to their father in the legends, the seals of Marie, Alix, Joanna, and perhaps Leonor show that these objects played a crucial role in the representation of lineage that was closely connected to political claims. These small wax items were therefore mighty objects, expressing pre‐sent authority in terms of kinship and heritage. But does this mean that coins and seals were the result of women’s ability to act or that they otherwise supported women in the exercise of power? The answer to this question requires a nuanced analysis of each individual’s context and her margin to act.

In Matilda’s case, the coin type on which she is represented does not offer a straightforward testimony of her rule during Henry’s absence. Yet, these small pieces of silver illustrate how much the royal daughter’s presence mattered to the duke and this, in turn, must have given her leverage, especially with an heir on its way. As for Joanna, if our assessment were based solely on her surviving seal, it would be difficult to determine to what extent Joanna was able to impact other people’s lives. However, the very existence of this seal—on which traces of wax have been found—tells us that she issued documents, attesting to her ability to confirm, deny, and negotiate matters of importance. Likewise, the power to make such decisions is manifested by the presence of Leonor’s seal attached to a charter in which she placed the Becket altar in Toledo Cathedral under her protection. Both a symbolic and a legal representation of the queen, the seal functioned as a surrogate for Leonor. By imprinting it in wax, she strengthened and confirmed the act with her own hand. This was Leonor’s way of keeping alive the endowment made by Alfonso’s former tutor and his wife, with which she also sought to ensure that she and her husband would be commemorated perpetually. Far from mute items, these women’s coins and seals invite us to respond to them as telling objects that give voice to the different ways by which the medieval elite sought to promote their positions, including their status as spouses as well as by means of their dynastic ties.

See endnotes and bibliography at source.

Chapter 2 (37-88) from Medieval Women, Material Culture, and Power: Matilda Plantagenet and Her Sisters, by Jitske Jasperse (Arc Humanities Press, 08.31.2020), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.