Christine de Pizan’s work performs a medieval version of feminist fabulation.

By Dr. Christine Chism

Professor English

University of California Los Angeles

Introduction

Surprisingly, even in the dark archaic Greek myths one can detect glimmers of other options. Traces of alternative story lines in vase paintings and fragments of Greek literature hint that peaceful interactions, even romance, might have been possible outcomes. In the Greek myths about Amazons that have come down to us, war always triumphs over love. But outside Greek mythology, and beyond the Greek world, women warriors and male warriors might make love and war together as equals—and even live happily ever after.

Adrienne Mayor, The Amazons1

Like Adrienne Mayor, Christine de Pizan was fascinated by Amazons and by the ancient sources that described them.2 However, as a late fifteenth-century writer striving to make her living in the courts of France, she only had the Greek-framed versions to go on. She could not point to the Scythian excavations of bodies and grave goods that bolster Mayor’s account of historical warrior women who were admired rather than killed, or the Greek vase paintings that hint at other kinds of relations for them than war. But Christine de Pizan, like Mayor, could follow the “traces of alternative story lines” in her sources like an Ariadne thread to a vantage point outside and beyond classical misogynies, through a process of careful, multisourced, comparative research. In Le livre de la cité des dames (hereafter, LCD), she digs not just to enlarge the “glimmers of other options” but also to imbue them with urgent affective and political power. In doing so, she recovers a history erased by authoritative Greeks and the Romans, hand in hand with the antique patristic writers and medieval clergy: a history of women’s friendship in a staunch classical sense, where friendship is the bedrock of polity itself. De Pizan, like Mayor, had to look skeptically at the tragic or misogynist sources she received in order to re-trope and repurpose them toward an ideal of women’s friendship—with other women, with men, and with society at large—that could compel loyalty, urge virtue, and enact friendship in the very act of reading, In LCD de Pizan enlarges “glimmers of other options” into full-blown visions of an alternate sociality that equalizes women as friends and as friendly rather than consuming them.

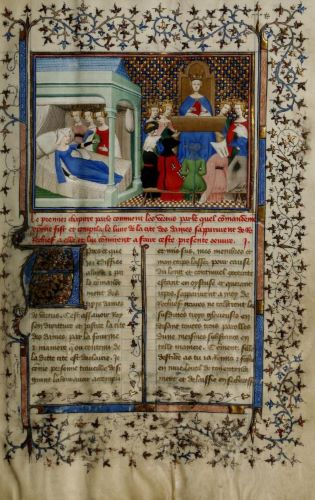

Christine de Pizan’s LCD performs a medieval version of feminist fabulation.3 It constructs a memory palace of historically separated exemplary women, thereby bringing about a new allegorically asynchronic polity of women.4 De Pizan’s City can, on the face of it, seem a singularly inert place, since its inhabitants are both the City’s subjects and its building blocks, and none of the women who inhabit it, locked each within their own historical milieu, can become friends with each other. The City’s siloed women thus structurally recapitulate the historical isolation of women under patriarchy. However, this allegorical isolation is tactical. By soliciting its readers’ imaginative interlocution, the Book invites a sociality not depicted between characters but rather enacted by women readers who are imagined as equally isolated and disheartened as the Book’s disconsolate narrator, and as remote from each other as the City’s exemplary women entrapped within separate histories. This essay explores the politics of the City’s virtual socialities, arguing that the City urges readers to perform idealized women’s friendship as an imagined community across time, as powerful and galvanizing as the idealized masculinized friendships found in the medieval intertexts of Cicero’s De amicitia.

The first section of this essay explores the idea of women’s virtuous friendship as a form of needful solidarity in a hostile world, foregrounding the crucial role of women’s alliances materialized in5 books: acts of reading become acts of friendship with and between women. The second section of this essay examines the allegorical frame of the LCD as an act of historical redress possible only between virtuous women, energized but not imprisoned by their history of wrongs. I read the compact between the narrator, Rea-son, Rectitude, and Justice in the light of discourses of virtuous friendship between men, derived from Cicero’s De amicitia, and deeply at play in one of de Pizan’s chief sources and literary models, Dante. As in Dante’s Convivio and Divine Comedy, friendship is mediated by the intimacies of vernacular language, which is concretized and personified into a fast friend all on its own, animated in readings and in writings. The third section of this essay looks at the actual architecture of the LCD. I summarize the antique, pagan, and Christian women who fabricate it and are joined by it and analyze the ways that de Pizan performs friendship to each woman in the city by reframing their stories to reproportionalize their deeds and virtues and to reverse masculinist reductions. Finally, I argue that Christine’s city functions most powerfully in the phenomenology of active reading and rewriting. Reading de Pizan’s text actively, skeptically, and interestedly makes feminist reading itself into a performance of friendship between women, especially if readers test de Pizan’s decisions and editing strategies, and thereby increase their own capacities for education and study. By reworlding women’s history into testing grounds for women’s readerly interpretation and interlocution, de Pizan offers her audiences a form of women’s friendship that gains power through its very virtuality and irreality. It makes women not only into worthy objects of study but also into worthy and active students, and it converts masculinist histories to histories written “by women and for women, with love.”6 Thus, through the education of its female readers, The LCD undertakes the profoundest act of ennobling friendship of all.

Women under Siege

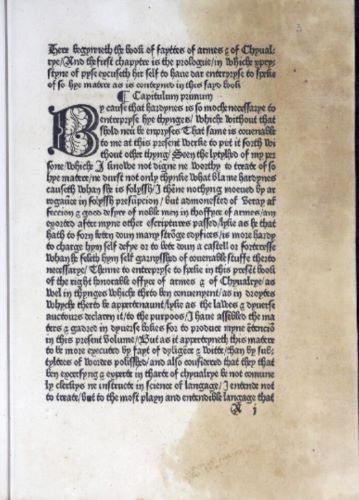

Alan Bray gives the silence on women’s friendship a prominent, anxiety-provoking place in the introduction to his groundbreaking study of early modern friendship, an anxiety that energizes the ultimate conclusion of The Friend—to show that “there has never been a time when male intimacy was possible in a space untouched by power and politics . . . For women it may have been different, in that silence between the lines.”7 This essay follows the rest of this collection in asserting that for women, it is not different. Rather, the pressures of power and politics are intensified, and the silence between the lines is an effect of those powerful political pressures. This anxious silence has been a clarion call to scholars studying premodern women’s friendship. Many scholars have found historical evidence as “formal and objective”8 as any could please, for women’s friendship, gatherings, culture, networks, and patronage, from letters and manuscript circulations, to Anglo-Saxon abbeys to fifteenth-century monastic architecture.9 That is not my project, however; this essay is more interested in the ways that literary cultural fantasy lays bare the stakes of that silencing as an effect of masculinist, androcentric ways of reading. Although de Pizan writes many histories, biographies, and treatises, her most memorable texts are fantastical allegories, even though they are culturally situated and leverage from a precise variety of social positions to intervene against the silencing induced by historical objectivism itself.10 Christine de Pizan’s (1364–1430) Livre de la cité de dames (1405) and its peritexts, Le chemin de longue étude (1403), Livre de fais d’armes et de chevalerie (1410), and the Livre de paix (1413), are genre-mixing compilations that bespeak complex literary genealogies even as they are driven by historical evidence and broad social experience. These texts do not even dwell on the word friendship, much less sworn friendship, though they do use oaths in various ways to exert power and declare commitment: they speak more of “alliance” and “citizens.” Their focus on alliance rather than affective bonding hooks into discourses of masculine virtuous friendship that make it the basis of public, political life,11 even as they respond to the limits of history by opening literary spaces for utopian social speculation.12

However, along with their political aims, de Pizan’s works do dramatize emotionally/politically resonant affections both between women and between women and men. I argue that they address the vicious realities of medieval women’s oppression and isolation from other women by transforming reading itself into an act of friendship, inviting women readers into a community that is both virtuous rather than vicious, and asynchronically virtual rather than historically real.13 In this, they poise themselves against androcentric sociali-ties of reading, rooted particularly in classical and clerical misogynist traditions (which rely on equally asynchronous connections—say, between Eve or Jezebel and all women). Christine de Pizan’s allegorical works thus seize the potentials for social re-engineering that reading, education, and reasoned argument represent, taking them from the hands of misogynist writers, and in an act of friendly alliance, placing them into the hands of women readers and writers.

By transforming reading into a process of virtual friendly alliance, Christine de Pizan’s texts press hard against the line between the virtual and the “real,” as they offer an emotional reality to readers. Instead of “hate speech” they viralize friendship, through the technology of the day, the circulation of books and manuscripts. And in so doing, Christine de Pizan’s women-centered allegories open up a glimpse into the longer histories of womanly friendships that we are only now beginning to ratify through such historical and archaeological recovery projects as Adrienne Mayor’s richly evidential account of ancient Scythian Amazons, and through the literature-focused chapters in the present volume.

Combatting Misogynisms

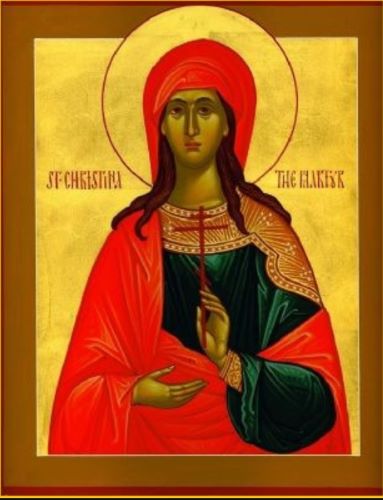

In reconceiving polity as based on women-inclusive friendship, Christine de Pizan’s texts have their work cut out for them. It is not for nothing that the LCD imagines a defensible city built on a strong foundation constructed of ancient powerful women (Amazons) twinned with sapient women (sibyls and goddesses). It requires impenetrable walls, studded with exemplars of female virtue culled from the androcentric histories of Virgil, Plutarch, Boccaccio, and Dante. It is roofed with the most formidable women saints that Christine de Pizan can muster, commanded by the Virgin Mary and including her own name-saint, St. Christina of Tyre, who is the fiercest of all. The resulting city is a time-crossing assemblage that mortars the ancient together with the contemporary to create a rugged, asynchronic fortress of honor.

Reminding readers how hostile are the surrounding masculinist reading cultures is a crucial part of the LCD’s structure. To that end, all three books of the LCD are driven by what I will call misogynisms that are drawn from St. Jerome and Theophrastus, Ovid and Virgil, Matheolus, Jean de Meun, and Boccaccio.14 These are doxic, toxic truisms about women, and they pervade Christine de Pizan’s text like a barrage of missiles whose equally relentless deflection comes to dramatize the City’s strength. The suffix ism connotes imitation and also affiliation: “isms” take sides with what they append to; and these misogynies don’t simply exfoliate like memes but also march together, actively and collaboratively. Thus, throughout the LCD, Christine the narrator voices misogynisms she has heard about women’s inconstancy, weakness, proneness to sin, ineducability, passionate madness, bad counsel, general depravity, and deficiency, and they all aggregate into a loathsome conglomerate, so widely attested and persuasively composited that one can come to doubt the goodness of a God who willingly created it. In LCD Christine de Pizan depicts the invasive and demoralizing force of these misogynisms in her own thought by giving them to her homodiegetic narrator, Christine, to articulate. To Christine, these misogynisms glide through textual histories like predatory bats, always looking for a place to settle and sap the self-determination of women readers.

How do these misogynies work their harm?15 Just as they gain a general power from their mutual affiliations, they are driven by an engine of exemplarization in which a single exemplar (say, Eve) or a skeletal constellation of them (say, Jezebel, Delilah, or Pasiphae) synecdochally come to stand for the entire species. The species in turn is concretized and energized by the specific historicity of the exemplar, thus gaining social credibility in a nightmare version of the process that Pierre Bourdieu describes as a mystery of ministry: “Group made man, he personifies a fictitious person, which he lifts out of the state of a simple aggregate of separate individuals, enabling them to act and speak, through him, ‘like a single person.’”16 Just as an elected representative substitutes for and receives the communal force of the group, creating it while incarnating it and becoming a fictitious person with redoubled social power, through a similar fictionalizing process the conscripted, slanderous representative casts an inculpating shadow over the whole group. When one chooses a single woman, say Eve or Jezebel, to represent all women, all women are reduced to a single, sin-originating face. Further, all subsequent individual women with flaws can be impressed as collaborators in a transhistorical sin-army, that becomes more credible the longer the list grows (hence the desire of misogynists to amass notebooks full of women).

The same synecdochic reduction can be applied to a single woman’s eventful life story, allowing it to be entirely commandeered by one detail or flaw. To take one instance, Dido can be ripped from her own timeline, annexed to a Roman imperialist mythography featuring Aeneas, dragooned into a fit of passion (which figuratively alludes to its own belated insertion by being attributed to a motivating goddess), in a tragic rewriting that would climax with her unforgettable self-immolation. In the process of getting caught up with Dido’s passion, we can disregard everything else in her history: her valiant escape from Phoenicia, her clever seizure of land-right in North Africa, her foundational success, her years of good leadership, her capacity for rule and self-governance: Queen Dido fades into tragic Dido, to inspire the horror and sympathy of men in a transhistorical affective “cosi fan tutti” that has reached tsunami force by the time Christine de Pizan encounters it.17 This reductive synecdoche can be applied to every notable woman in history, so that Zenobia’s long and successful sovereignty disappears behind the fictitious distaff she had to display in the Roman triumph that signaled her defeat, or Semiramis’s regnal power dwindles behind her incest. For each woman’s life, a historical or fictional flaw is enlarged to become the inescapable frame for the whole account (re-troped as tragedy or horror show), and thus she can be conscripted to join hands with her foremother, Eve, in a snowballing genealogy of evil that would make Benjamin’s afflicted Angel of History weep yet again.

How can one deal with these multitudinous misogynisms—this army of fictionally collaborative bats? Christine’s divine allegorical interlocutors, Rea-son, Rectitude, and Justice, refute these misogynisms promptly and judiciously, using a one-two punch of rational rebuttal followed by counterexamples, and each rebuttal thus creates a new focus for discussing the lives of the women who serve as counterexamples—a countergenealogy of feminine virtue, which snowballs into its own transhistorical force. In this way the LCD pins misogynisms down for the purposes of both logical and exemplary rebuttal, and then uses their own fictionalizing strategies of exemplarism, representation, and alliance to confect a counterhistory on the side of truth. Some misogynisms are acknowledged as half-truths, others are lies, while others actually invert the truth. For instance, in terms of women’s purported viciousness, de Pizan sees women as more intrinsically inclined to virtue than men—a situational essentialism she bases logically on women’s historical disempowerment and thus remoteness from the temptations of tyranny.

Yet these misogynisms with their trailing notebooks full of evil women cannot simply be reasoned away one by one, since they gain power through pervasiveness of their collective reiteration. Accordingly, Christine de Pizan’s defense becomes an almost statistical corrective: a refiguring of what counts as significant given sampling and ideological biases. First, de Pizan draws on a wider array of women than any of her sources to showcase the sheer diversity of feminine virtue. Second, her retellings reproportion and re-trope individual stories so that emplotments shift from provoking denigration or tragic defeat to reinforcing respect and assessing lasting gains.18 In the process, significant flaws such as Semiramis’s incest or Dido’s passion dwindle from catalysts to singular details among many other details. De Pizan thus changes women’s stories by writing, in Rachel Blau Duplessis’s terms, “beyond the endings” that foreclose possibilities of historical significance: carrying the women’s lives beyond marriage, defeat, or death, toward ongoing ennobling loves, virtuous service, and social utility.19 In most stories she compiles different sources to enrich the details that show historical friendships between famous women and those they loved, their families, friends, husbands, and peoples, while underscoring that the whole picture is complicated, extensive, and irreducible.

A case in point is de Pizan’s reframing of the story of the Sabine women, who are noted in many sources only for being the victims of rape by the settlers from Romulus’s army. In Livy’s account, which Christine works from and writes against, the women are endangered by their fathers, who had refused intermarriage rights to the Roman settlers. In response to this refusal, the rape becomes a successful Roman reproductive gambit, justified because the Roman men’s dynastic urgencies are paramount. However, this outcome requires a horrific betrayal of hospitality rights. The Sabine families are invited to attend celebratory games at the new city of Rome, hosted by individual Romans in their houses, and then at a prearranged signal, their daughters are abducted by their hosts, with the most beautiful earmarked for the noblest Roman patricians. The Sabine paterfamiliases are driven back, leaving the city in rage, while Romulus assures the daughters that they will be honorably married, share citizenship and property rights with their husbands, and be mothers to a new race of freemen (and what is better than to be free? the captives are asked, with some irony). But what really gains the Sabine women’s assent is their individual captors “justifying their acts by their lust and love—the plea most moving of all to a woman’s temper” [purgantium cupiditate atque amore, quae maxime ad muliebre ingenium efficaces preces sunt], as Livy, secure in his grasp of women’s natures, assures us.20 Their angry families then go to war and beat the Romans almost to a standstill. At that point, the women intervene to stop the two armies, apparently convinced by Romulus’s argument and the interests of their children.

Christine de Pizan’s interpolation takes us beyond the rape, underscoring instead how the women take charge of their circumstances and rewrite tragedy into triumph. They do this by organizing. Their story crystallizes the personal and political force of friendship that de Pizan envisions throughout her book. Hearing that their fathers and brothers are preparing to attack the settlers and take back their daughters, the queen of the Sabines addresses her fellow victims and proposes an act of what amounts to civil disobedience: to place their bodies and those of their children between the encroaching armies and plead for peace.

“Honored Sabine ladies, my dear sisters and companions, you know how we were abducted by our husbands and how this caused our fathers and relatives to wage war on our husbands, and our husbands on them. There is no way whatsoever that this deadly conflict can be brought to an end or continue without it being to our detriment, no matter who wins . . . What is done is done and cannot be undone. That is why I think it would be a very good idea if we could find a way to end this war and reestablish peace. If you are willing to trust my advice, follow me, and do as I do, I am convinced that we can bring this matter to a good end.”

[“Dames honnourees de Sabine, mes chieres suers et compaignes, vous savez le ravissment qui fu fait de nous de noz maris, pour laquel cause nos peres et parens leur mainent guerre et noz maris a eulx. Sy ne puet de nulle part en nulle manière terminer ceste mortelle guerre ne estre maintenue, qui qu’en ait la vittoire que ce ne soit a nostre prejudice . . . ce qui est fait est fait et ne puet autrement estre. Et pour ce me semble que moult seroit grant bien se aucun conseil, par nous y povoit estre trouvé que paix fust mise en cestre guerre. Et se mon conseil en voulez croirre et me suivre et faire ce que je feray, je tiens que de ce vendrons nous bien a chief.”]21

In this speech (which is not present in Livy), the Queen of the Sabines not only organizes her fellow victims but models a kind of leadership that is antithetical to Livy’s Romulus. She invites them to a political collaboration rather than an imperial rape. She addresses them as Dames honnourees, honorable rather than dishonored, as dear sisters and companions (chieres suers et compaignes) rather than dynastic conveniences. She acknowledges the rape as rape (ravissment) before going on to talk about the virtuous necessity that brought love for children and therefore husbands out of acts of violence at the cross-section of past and future families). Most of all, she places that rape in a past that should not continue to determine the women’s lives. Rather, they should acknowledge that through no choice of their own, they now have deep affiliations not only with their Sabine families and kinfolk but also with the Romans. Whoever wins, either their children, or their fathers and kin, will suffer. She urges them to decline the roles of motivators for masculine action,22 defined only by the crime done to them and its ramifications for the honor of their Sabine paterfamiliases. The women assent as a body, a moment of public consent, “elles obeyroyent tres voulentiers” (Curnow, LCD 867), that again counter-indicts the assumption of naturalized consent implicit in Livy. The queen’s speech is a declaration of friendship, then, in at least three Ciceronian ways: (1) it restores honor and virtue to the women, (2) it invites them to a loving alliance in which they become equals in action, and (3) it rouses them to further acts of civic virtue. The women take their children and go with loose hair and bare feet to stand between the two armies, shouting to them in a public, political declaration of love, friendship, and double affiliation: “Beloved fathers and kinsmen, beloved husbands, for God’s sake, make peace! If not, we are prepared to die under the hoofs of your horses.” [“Pares et parens tres chiers, et seigneurs maris tres amez, pour Dieu faittes paix! Ou se ce nom, yoy toutes voulons mourir soubs les piez de voz chevaulx!”] (de Bourgault and Kingston, LCD 137; Curnow, LCD 867).

The brashness and self-sacrifice of the women’s stratagem is a seizure of gendered discourse itself. It troubles categorical distinctions between men and women by simultaneously seizing control of a masculinized public space (the battlefield) and making a feminized affective plea (they strategically dress like victims, hair uncovered, kneeling, and in tears).23 This act startles the men on both sides into a new relationship with each other:

The husbands, who saw their wives and children before them in tears, were shocked and certainly most unwilling to run at them. The fathers were equally moved by seeing their daughters in tears. Touched by the women’s humble plea, the two sides looked at each other and their rage faded, replaced by the filial piety sons feel for their fathers. Both sides felt compelled to throw down their weapons, embrace each other, and make peace. Romulus led the king of the Sabines, his father-in-law, into the city and welcomed him and all his company with great honor. That is how the good sense and moral courage of the queen and her ladies saved the Romans and the Sabines from destruction.

[Les maris qui la virent plourans leurs femmes et leurs enffans moult furent esmerveilliez et bien enuiz—n’est pas doubte courussent parmy eulx. Sem-bablement appitoya et attendry moult les cuers aux peres d’ainsi vecir leurs filles. Parquoy, regardant les uns les autres pour la pitié des dames qui si humblement les prioyent, tourna felonnie en amoureuse pitié comme de filz a peres tant que ilz furent contrains a gitter just leurs armes d’ambedeux pars et d’aler embracier les une les autres et de faire paix. Romulus mena le roy de Sabins, son sire, en sa cite et grandement l’onnoura et toute la compagnie. A ainsi par le scens et vertu de celle royne et de dames furent gardéz les Rommains et les Sabins d’estre destruiz.] (de Bourgault, LCD 137; Curnow 867–68)

De Pizan’s account of this intervention shows how the women deliberately adopt the semiotics of victimhood (the very victimhood that Livy’s account attempts first to instrumentalize and then to smooth over) because they know that that is what their husbands and kin expect from women. And sure enough, it’s their tears that the men read and their humility that shocks and arrests both their kin and their lord-husbands (seigneurs maris—de Pizan never lets us forget the coercion implicit in their marriages). However, to the reader, this feminine humility has already been framed by a feminine political alliance based in pragmatism and daring. Transplanting feminine tears into the hypermasculinized center of the battlefield rather than its decorous margins effectively regenders war as central to women’s concerns.

And yet the appeal that exerts the most effective alchemy on the men is not the implicit gender trouble of the women’s intervention but the double love they declare, which transforms the two army’s zero-sum homosocial conflict into something else. These doubly affiliated women choose to inhabit a place that could be read by one army as accession to their rape and by the other as continued affiliation despite rape and overcoming it. As though the pressure of this double vision were a catalyst, suddenly and miraculously the men look at each other and see each other as the women see them—as kin. The women’s act of friendship with each other catalyzes the armies’ mutual hate into filial love (tourna felonnie en amoureuse pitié comme de filz a peres), compelling the men (ilz furent contrains) to abandon their contest over masculine honor and to see with women’s eyes: the eyes of friendship and familiarity. The patriotic gains are immediate, as de Pizan presses home. The provocative virtue enacted in this theater of loving victimhood will enable both the Sabines and the Romans to survive. The new invitation of the Sabines into Rome, with all honor, redresses the horrific breach in hospitality that the previous rapes had inflicted.

By focusing on this moment of feminine alliance, rather than Livy’s rape, or his imperatives of empire, or his staging of honor and revenge, or his recourse to the women’s susceptibility to male passion which comes from their natures, Christine de Pizan unwrites Livy. She takes the story beyond the triumphalist zero-sum logic of Roman imperial colonialism to a new zone of collaborative alliance. These women become politically significant by bringing women’s perspectives into masculine public spaces, to serve virtuously their own needs and those of their countries.

This anecdote is just one of the most forceful of many such throughout the LCD. By publicly dramatizing women’s virtue as rational, heartfelt, and above all politically beneficial, de Pizan shows how friendly love and alliance between women extends the profile for Ciceronian civic friendship beyond men, to the betterment of both men and women and the lands they inhabit. The drama of these detournements casts light on the twofold tactics of LCD’s battle with misogynisms: both critical (rational point-by-point rebuttal) and countervisionary (affective narrative cruxes). The high-walled, enduring city of ladies, with its call to unite women readers in friendly citizenship, promises to do this visionary work. The LCD envisions a defensible city that combines the military prowess of Amazonia with the liberating luster and sempiternity of the celestial Jerusalem itself.

My dear ladies . . . you have good reason . . . to rejoice in God and virtuous-ness at seeing this new city completed. It will not only serve as a refuge for all of you virtuous women but also as a bastion from which to defend yourself against your enemies and assailants, provided you guard it well. You can see that the material used in its construction is pure virtue, shining so brightly that you may see your reflection in it.

[Mes tres chieres dames . . . si avez cause orendroit . . . de vous esjouyr ver-tueusement en Dieu et bonnes meurs par ceste nouvelle cite veoir, parfette, qui puet ester non mie seullement le reffuge de vou toutes, c’est a entendre de vertueuses, mais aussi la deffense et garde contre voz annemis et assaillans, si bien la gardez. Car vous povez veoir que la matière dont elle est faitte est toute de vertu, voire, si reluysant que toutes vous y povez mirer.] (de Bour-gault 219; Curnow 1031–32).

Reflected in the city thus are not only the virtuous women of the past but the virtuous woman readers to come, who can see themselves in its heavenly mirror. The iconography of an ethical heaven is offered to all who need such a refuge, so long as they ally with it and take up virtuous arms to guard it.

That vigilance makes friendship a political act, an act of defense against war, even as it draws on feminized, spiritual tropes, such as mirroring. In subsequent treatises, such as the Book of Deeds and Chivalry and the Book of Peace, Christine refined the political work of friendship or amity as a national virtue that could resist the centrifugal forces of masculinist elite warfare she saw tearing turn-of-the-century France apart. The LCD at its most aspirational imagines a powerful role for women themselves as sowers of a defensible peace. They are invited to become like the Sabine women, ravaged by andro-centric histories, but working together in ways that benefit man and women alike, to enact a national-scaled politics of friendship. In this time-crossing feminist alliance, reading is transformed from androcentric gaslighting into a virtual alliance of women who can write forward in their turn.

Invisible Cities: Reading for Friendship

The experience of reading in de Pizan’s works is intimate, always imagined as an intersubjective exchange, for good or ill, even when allegorical personification is not involved (as it often is in de Pizan’s texts) to embody the inter-course. For instance, when de Pizan reads Jean le Fèvre de Resson’s recent French translation of Mathieu of Boulogne’s Liber lamentationum Matheoluli, a misogynist treatise against marriage, Matheolus worms his way into her consciousness like a sapper undermining her morale from within, until she is sick at heart and cursing herself and God for allowing her to be born into the body of a woman.

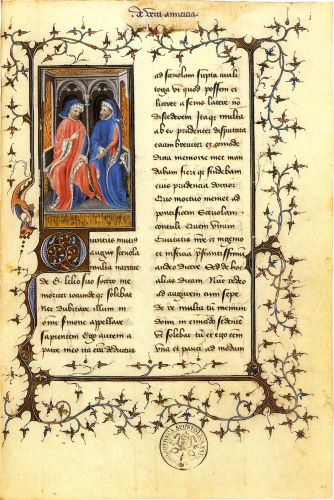

As de Pizan dramatizes how books infiltrate readerly consciousness, she also experiments with how books are activated in readers through a reader’s idiolectic processes of meaning-making and frustration. Frequently books gain bodies in the process and become physically interactive as mentors and friends (or detractors and enemies such as Matheolus). For instance, in books 3 and 4 of Le Livre des faits d’armes et de chevalerie (1410), the act of shifting to a new source becomes a personal conversation with the author of that source. As Christine de Pizan proceeds to engage at length with Honoré de Bouvet’s Arbre des battailles’s granular treatments of military legality and best practice, she dramatizes this as a visionary visit from Honoré de Bouvet himself: in the form of a “solemn man in clerical garb” [“tres solempnel d’abit de friere”] who addresses her as “Dear Friend, Christine” [“Chere amy, Christine”].24 De Bouvet addresses de Pizan as an old friend, and he consents to be her mentor for her current project. De Pizan references a history of past textual liaisons:

“O worthy Master, I know that you are one whose work I admire greatly and have admired as long as I can recall; your haunting and virtuous presence has already helped me, thanks be to God, to bring to a successful conclusion many fine undertakings. Certainly I am very glad to have your company.”

[O digne maistre, je congnois que tu es celluy estude que j’ame et tant ay amé que plus de riens ne me souvient et par laquelle vertu et frequentation ay, la Dieu grace achevée maintes belles entreprises. Certes de ta compaignie suis tres joyeuse . . . BNF 1183 f. 49.].

The collaborative compact between de Pizan and de Bouvet references a longer relationship of continual revisitation and endowment, more like a long-term collaboration. Textual friendship is enacted in active, ongoing iterations of reading and usage that deepen over time. Further, while textual friendships endear writers to readers, they can also empower them to become better writers on their own and reach other readers in turn.

By creating friendships with other texts, Pizan models for her own read-ers the power to be gained by compiling old books into new collaborations, to get needful work done. De Pizan thus repurposes even the most androcentric literary histories and strategies: Livian empire-building, Boethian protrepsis, Dante’s comedic world-making. Even Jean de Meun’s debates in the Roman de la rose (which she publicly critiqued for their misogynist content) modeled forensic flexibilities that helped her turn the genre of dream vision allegory toward her own needful interventions.

So if books can be friends with writers and readers, how is textual friend-ship transformative? In LCD de Pizan dramatizes how books can become friendly catalysts for virtuous knowledge, morale, and solidarity in two ways. The first is diegetic: faculty allegories can model women mentoring other women, even as they intermesh allegorical characters with the reader’s internal thoughts, feelings, and urgencies. The second way is extradiegetic: by rewriting historical characters in such a way that they can step out of the worlds of the textual past and emerge affectively into the reader’s present everyday life. Just as biblical drama allowed the re-presenting of remote scrip-tural truths with medieval contemporary worlds, reading Christine de Pizan’s composite histories (whether those of virtuous women, literary knowledge systems, or French national history) provoke not only an aesthetic reading but also what Louise Rosenblatt calls an efferent one (from Latin efferre: to carry away, produce, elevate): something readers carry away with them.25 This is not so much a lesson or a message as a set of new ways of engaging in the world. Efferent readings galvanize social, political, ethical action. Christine de Pizan’s allegorical journeys can arrest readers with their vividness, fluidity, and strangeness, and energize their own world-building alliance-schemes. This means that most crucial friendships for Christine’s projects are not those she depicts within her vision-texts but rather those that her books provoke readers to enact.

Thus, the most vivid diegetic models of de Pizan’s seizure and detournement of the modes of Ciceronian friendship are the relationships between her narrators and her mentors, who are at once her idealized doubles gleaned from her reading of other texts and intimately reimagined, and the divine, profoundly illustrious, and remote daughters of God.26 In Chemin de longue étude, we find the sibyl Almathea; in LCD, Reason, Rectitude, and Justice; and in the Avision, the princess who is simultaneously the human capacity for divine insight, the holy church, and the nation of France. All are gendered female, and all occupy a richly mixed space between subject and object, text and reader, past and present, self and larger world, because reading is exactly the intersubjective space where such liaisons can happen. In modeling these textual friendships, Christine grasps the fully transactional nature of reading and the active, emotional, multifaceted, ultimately political activity the reader performs.

This transactionality is underscored through the composite mentors of LCD: the alliance of Reason (with her mirror), Rectitude (with her ruler), and Justice (with her measuring cup) as they work together to guide, correct, and energize Christine. The very homeliness of their insignia, as tools any woman might use around the house, actualizes their ability to translate divine reflection and ethical assessment into productive action. Justice declares that they work in tandem and that their cooperative division of labor makes them supremely effective: “And we, the three ladies you see before you, are all one: we could not function without each other. What the first one decides, the second one puts into effect, while I, the third one, ensure that it is brought to fruition.” As they restore moral vision to Christine, their alliance makes friendship operational. Once the LCD is finished, it can become a replicant mentor and go out into the world to comfort, teach, support, and inspire other women, by showing them that they are not alone. In this way LCD mobilizes Ciceronian models of friendship by building virtue into its transmission, but it flouts those models by making it elective, promiscuous, diverse, inclusive, and textually reproductive. Where Cicero considered true male–male virtuous love to be rare almost to extinction, de Pizan shows that women’s virtuous love can be electively transacted across the generations, through efferent reading and inspired re-creation.

Christine de Pizan goes out of her way to stress the heterogeneity of women’s virtue across history, offering her readers a huge variety of possible identifications, carefully allocated the parts of the city de Pizan considers best for them.27 The three parts of the LCD divide into three books which describe different levels of construction: (1) foundations and ramparts, (2) walls and buildings, and (3) rooftops and towers. At the foundations are ancient pagan illustrious women, whom de Pizan salvages from androcentric histories that have exceptionalized, vilified, or fetishized them. In the process, she per-mutes their histories to capitalize on their virtuous friendship not only to other women but to their families, countries, and allies. There are two groups of women at the City’s foundations: (1) women of power, equal to the best of men in both battle and governance; and (2) women of knowledge. Sovereign women include Semiramis, the Amazons, including their founding queens Lampheto and Marpasia, Thamaris, Menalyppe and Hippolita; and then Pen-thesilea (who demonstrated her virtuous friendship for Hector by dying to avenge him), Zenobia, Artemisia, Lilia, Fredegund of France, who fought with her sons in her arms, Camilla, and Berenice. The final exemplar, Cloelia, gives us a powerful figure for de Pizan’s own feminist salvage project. Cloelia was a seemingly helpless virgin among many taken hostage and imprisoned by a Roman adversary. She broke her fellow hostages out of prison with the help of a single horse to carry them one by one across a river, an accomplishment that wrung reluctant admiration even out of the Romans. De Pizan’s salvage proj-ect performs a similar service to the woman captured in masculinist narra-tives, extracting them and working them one by one into the fabric of the City.

The second group of knowledgeable women at the foundations of de Pizan’s City includes poets and writers (such as Cornificia, Proba, and Sap-pho), oracles and magicians (such as Manto, Medea, and Circe), sibyls (such as Nicostrata), and inventors (including some euhemerized goddesses like Minerva, Ceres, and Isis, whom de Pizan humanizes into very accomplished women who innovated new technologies). An account of ancient painters—Thamaris, Irene, and Marcia—prompts Christine to leap forward in time and praise one of her own scribal collaborators, a fifteenth-century Parisian illuminator named Anastasia. Finally, we get prudential women who showcase the ethical utilities of knowledge: Gaia Cyrilla, Dido of Carthage (now a figure of good governance rather than passion), Ops of Crete, and Lavinia of Latinum. Placing a varied consortium of antique pagan power, knowledge, and wisdom at the bedrock of the city allows Christine to initiate a variety of virtuous genealogies that the next level of the city can ramify forward in time.

The second book of LCD gives us the buildings of the city—its middle stratum. At this level, figures from different times and traditions mingle freely and promiscuously in defiance of the temporal and religious segregation maintained in de Pizan’s central sources, particularly Boccaccio’s De mulieribus claris.28 This middle stratum of the city is the most asynchronous and mixed space in the LCD, weaving from the ancient to the contemporary; from queens to peasant girls; from history to legend to romance and literature. We can see how women operate beneficially within a huge range of social relationships, both with other women and with men. Their loving virtue is made visible as the social adhesive that preserves dynasties and civilizations. Their fidelity to men at all costs parts company with many contemporary feminisms, but this is precisely where Christine de Pizan touches most insistently on the power of women’s friendship to pervade the lives of those it touches in enno-bling Ciceronian ways.

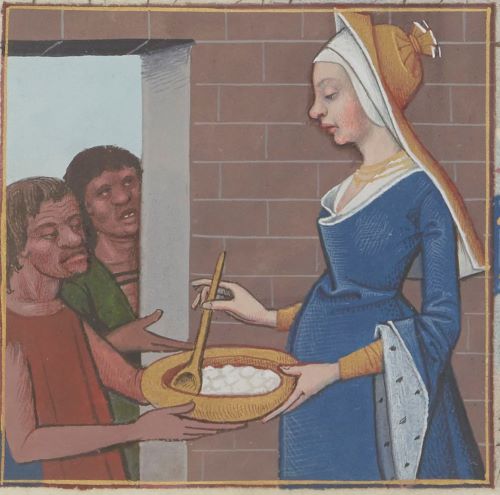

Rectitude is the genia loci for this central stratum. Thus, this level devotes itself to rectifying particularly insidious misogynisms: those that desocialize women by making them monsters who corrode human relationships. Rectitude combats these misogynisms by showing women as faithful protectors of the ties that bind families and societies together. Throughout the book, women work as powerful, kindly mediators, enacting the power of friendly interces-sion by weaving peace amid hate. The book begins with prophets and emissaries who mediate God’s word to the world: the ten sibyls and other oracles. It goes on to dutiful daughters (Drypetina, Hypsipyle, Claudine, Griselda); meritorious wives (Hyspsicratea, Triaria, Artemisia, Argia, Agrippina, Julia, Tertia Aemilia, etc.); wives faithful to clerical husbands (Xanthippe, Pompeia), to old husbands (Sulpicia); to lepers (contemporary women); women who keep their husband’s secrets at all costs (Portia, Curia); good advisors to husbands (Antonia, Roxanne); and social benefactors of many kinds: rescuers of good men (Thermutis) or dispatchers of bad ones (Judith); culminating with women who save whole nations (Esther, Deborah, and the Sabine women, discussed above, Veturia, Clotilde, the women who sheltered the first apostles, and Catulla, who kept St. Denis’s body for France). Guided by Rectitude, Christine moves from women who augment social good to those who repay gratefully the social goods they are given, such as education: Hortensia of Rome (ancient) and Novella of Bologna (contemporary). Other women repay a good marriage by remaining chaste (various biblical, pagan, and Jewish women) or exhibit great beauty while remaining chaste (Mariamne, Antonia). Then we find the women who repay great wrong with virtue: victims of rape who requite dishonor on their own terms (Lucrecia, wife of King Ortiagon of Galatia, Hippo, Virginia); victims of abuse who persist, survive, and do good (Griselda, Florence of Rome, Sicurano); and women faithful in love unto death (Dido, Medea, Thisbe, Hero, Ghismoda, Lisabetta, Dame de Fayel, the Chatelaine of Vergie, Isolde, Deianera). Then come a group of women misunderstood or appropriated, who became famous by chance or because of men’s desire for them, usu-ally to their own detriment (Juno, Europa, Jocasta, Medusa, Helen, Polyxena), and women who like elegant fashion and shouldn’t be denigrated as mantraps since not everything is about men (Claudine, Lucretia, and Queen Blanche mother of St. Louis)—a section that targets the androcentrism of de Pizan’s sources. A final group stresses women’s friendship and generous giving to the unfortunate when charity benefits everyone (Busa of Apulia, Marguerite de la Riviere, Isabeau of Bavaria [the current queen of France], the Duchess of Berry, the Duchess of Orleans, and even more contemporary figures, commoners as well as the elite). From the ancient women who mediate God’s wisdom and foresight to the world, to the contemporary women whose charitable giving enacts God’s love in the world, women are presented as donors and keepers of the troths of love and friendship that bind society together.

The third and final level of the city is the roofs and towers, under the administration of lady Justice, and it contains only Christian saints from across history. Here Christine welcomes the queen of Heaven, Mary herself, into the city, in a formal triumph grandiose enough to ensure that Ave replaces Eva as the delegate of womankind. Mary illuminates the renovated dialectical mystery of ministry of the female sex by descending willingly to be written into the fabric of the city, a citizen among others, but its most paramount representative.

The hagiographies and martyrologies that follow, like the stories of the ancient Amazons at the city’s foundations, underscore women’s absolute indomitability, showing that what Amazon warriors begin, saintly Christian women can finish (and often with even more ferocity). This is particularly evident in the melodrama of St. Christine of Tyre, Christine de Pizan’s own name-saint. The story opens an allegorical window onto one of Christine de Pizan’s favorite tropes: how misfortune can be turned into new opportunity. When Christine of Tyr adopts Christianity, her pagan father Urban imprisons and tortures her, and finally throws her into the sea. Christine prays to Christ himself to baptize her in the Mediterranean, since she’s there already, turning the instrument of execution into the means of regeneration, and he obliges. Crowned with a star by Christ himself, the newly baptized Christine gains a lethal power over those who oppose her: the power to reflect their own hatred back upon themselves. That night the father who tortured and tried to kill her is tortured and killed by a devil. Arraigned before a tribunal, Christine tames snakes and raises the dead, while two prosecuting judges die in trying to dispatch her. The last judge, Julian, tears her breasts off (thereby giving her a double Amazon insignia), but she bleeds milk rather than blood—replacing loss of lifeblood with gift of nurture. She preaches and he tears out most of her tongue, but rather than silencing her, this paradoxically invests her speech with even more force and clarity. Julian has a final dig at the remains of her tongue, but she spits the last piece out—into his eye, where it blinds him—and continues to speak: “Do you really think, you tyrant, that cutting out my tongue will stop me from blessing God, when my soul will eternally bless Him and yours will be damned forever? You failed to heed my words, so it is only fair that my tongue has blinded you” [Tirant, que te vault avoir couppee ma langue adfin que elle ne beneysse Dieu, quant mon esperit a tousjours le beneystra et le tien demourera perpetual en maleysson? Et pource que tu ne congnois ma parole, c’est bien raison que ma langue t’ait aveuglé] (de Bour-gault 207; Curnow 1009). Ultimately, only distance weapons—two arrows—can take her down, and, instantly arrowlike, she flies up to God.

This story that bears Christine’s name suggests that although Christine de Pizan passionately believes in the cause of peace, patience, and social cohesion and seizes the tropes of friendship to intimate these causes in heartfelt ways, sometimes peace is not enough. Those who attack women need to be met with a reflection of their own force. In book 3, driven by the sigils of Justice, the fervor of Christian witness, and violent strictures of martyrology, a ferocious anger bursts forth. The sheer rage of St. Christine’s story as it alchemizes death into new life, silence into speech, and speech into a blinding weapon against those who will not see is the hostile face that the hospitable City must turn to its detractors. In that face, virtue becomes not only a shield to mirror women’s virtue but a sword against those who decry it.

The three levels of the city compound so many stories of so many genres and types that readers may pick and choose; this variety is tactical. De Pizan makes the structural logic so clear that one can skim, and thus some things will stand out at one reading and others at subsequent ones. The diversity of the LCD’s allegorical and historical characters refuses to provide ideal models for emulation—that would risk reducing readerly agency and thus losing readerly love. Rather, these historical women appeal not through likeness, or ideality, but through unlikeness and historicity. They do not model female virtue so much as measure the wider latitudes of virtuous femininity itself, across time and cultural difference.

Readers who have already read some of these stories from other sources will find another insight as well. When de Pizan retells familiar tales differently, she exemplifies feminist reframing practices. She offers women readers a toolbox for actively reading to demonstrate virtuous friendship toward notable women who are all too often rolled, like Chaucer’s poor Criseyde, upon many a tongue. In sum, the LCD not only represents but performs a feminist intervention against the imaginative strictures of androcentric narrative cultures. De Pizan enacts friendship with women readers by (1) critiquing misogynisms as they occur in a thoroughgoing attempt at feminist reprogramming, (2) offering a variety of imaginative affiliations with other historical women across time to many kinds of readers, and (3) revivifying possibilities of new writing and thinking by modeling how narratives can be reproportionalized and redressed so that the complexity of woman’s lives, multiple affiliations, and political service can become visible.

As its more than two hundred manuscripts show, de Pizan’s book was an invitation to creative collaboration that many subsequent readers, artists, and scholars have been eager to take up. These include texts owned by Anne de Beaujeu, Gabrielle de Bourbon, Marguerite de Navarre, Georgette de Montenay, and Margaret of Austria.29 It jumps media from architectural allegory and plain text to illuminated text to painting to tapestry. Queen Elizabeth I herself owned a six-section tapestry of the City of Ladies, each section extend-ing eight by five meters; she could literally walk the City across fifty square meters of her house.30 The LCD’s complicated and very rich reception history attests at once to its affective power, its creative invasiveness across media, and the fear it induced in those who tried to appropriate or control it.31 The Book of the City of Ladies ultimately works because the City escapes de Pizan’s book and becomes an open-ended mobile assemblage, spawning a thousand new cities in the process of reading. To be sure, de Pizan’s Ciceronian focus on public virtue at whatever social level limits her congeniality to many of the socially denigrated women treated in this volume, from Harris’s obscene and educative gossips and cummars, to Lochrie’s excavation of a half-occluded likeness of feeling in Chaucer’s Sultaness or Wife of Bath, to Vishnuvajjala’s beautifully complicated Gaynor. However, the text’s virtuous elitism itself can be discarded and critiqued by its readers, even as they adopt its writerly strategies. In the end, LCD models a form of feminist fabulation that could be seized upon by women who needed it and taken anywhere—in public or in private—through reading, which itself muddles public and private boundaries in both diegetic and extradiegetic ways32 to extend a politics of women’s friendship across the ages.

Reading a book as a collaboration with a friend is to perform friendship at a distance, while also realizing it is as intimate as a personification of one’s own thoughts. As Anderson argues in her afterword, this paradox of intimacy and remoteness is at the heart of this volume.33 The afterlife of de Pizan’s City resurges in the networks of women who declared their friendship to the City through manuscript exchange and tapestry creation, material support, and notional affiliation. Similar traceworks of friendly women have been made visible by archivists both careful and transgressive, in this volume and, it is to be hoped, many others to come. The Amazons are still out there, waiting to be heard.

Endnotes

- Adrienne Mayor, The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women Across the Ancient World (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2016), 30.

- This essay is dedicated to the fellow scholars and researchers with whom I’ve enjoyed many conversations about Christine de Pizan over the past decade, but especially to Alexandra Verini and Lauren Rebecca King, whose work explores respectively the utopian tactics of feminine alliance and readerly identification as a protreptic allure.

- Feminist fabulation is a radical relationship with existing archives that foregrounds its own transgressive epistemologies. It draws attention to its own fictionalizing strategies, highlighting the relationship of the researcher-writer to the texts she receives as a zone of intense, intersubjective exchange that acknowledges and enjoys its own fictionality; see Holly Pester, “Archive Fanfiction: Experimental Archive Research Methodologies and Feminist Epistemological Tactics,” feminist review 115 (2017): 114–29; Marleen S. Barr, Feminist Fabulation: Space/Postmodern Fiction (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1992).

- For de Pizan’s memory-work, see Margarete Zimmerman, “Christine de Pizan: Memory’s Architect,” in Christine de Pizan: A Casebook, ed. Barbara K. Altmann and Deborah L. McGrady (New York and London: Routledge, 2003), 57–81.

- Alexandra Verini shows how feminist alliance in Christine de Pizan meddles with the distinction between public and private spaces to create feminotopian communities. This essay owes thanks for her work and unpublished research by Becky King on the pedagogical force of reading in Christine de Pizan: Alexandra Verini, “Medieval Models of Female Friendship in Christine de Pizan’s The Book of the City of Ladies and Margery Kempe’s The Book of Margery Kempe,” Feminist Studies 42, no. 2 (2016): 365–91.

- Joanna Russ, Magic Mommas, Trembling Sisters, Puritans, and Perverts (New York: Crossing Press, 1985), 79.

- Alan Bray, The Friend (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 11.

- Bray, Friend, 25.

- For a starting place, see Roberta Gilchrist, Gender and Material Culture: The Archaeology of Religious Women (New York and London: Routledge, 1997); Jocelyn Wogan-Browne, Saints’ Lives and Women’s Literary Culture: c. 1150–1300 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001); Mary C. Erler, Women, Reading, and Piety in Late Medieval England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

- Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Boston: Beacon Press, 1997).

- Lochrie and Vishnuvajjala, “Introduction.”

- Verini, “Medieval Models,” and in this volume, “Sisters and Friends.”

- For the affective force of asynchronic contact across time, see Carolyn Dinshaw, How Soon Is Now? Medieval Texts, Actual Readers, and the Queerness of Time (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012).

- Rosaline Brown-Grant usefully discusses de Pizan’s address to medieval misogynist traditions in “Christine de Pizan as a Defender of Women,” in Altmann and McGrady, Casebook, 81–100.

- Carissa M. Harris, Obscene Pedagogies: Transgressive Talk and Sexual Education in Late Medieval Britain (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2018), 1–26; R. Howard Bloch, Medieval Misogyny and the Invention of Western Romantic Love (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991).

- Pierre Bourdieu, Language and Symbolic Power, trans. Gino Raymond and Matthew Adamson (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991).

- Thomas Hahn, “Don’t Cry for Me, Augustinus: Dido and the Dangers of Empathy,” in Truth and Tales: Cultural Mobility and Medieval Media, ed. Fiona Somerset and Nicholas Watson (Columbus: The Ohio State University Press, 2015), 41–59.

- See Hayden White’s “The Historical Text and Literary Artifact,” in Tropics of Discourse (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1978), 81–199, for a discussion of the power of reframing and re-troping historical retellings and the generic shifts that result.

- Rachel Blau Duplessis, Writing Beyond the Ending: The Narrative Strategies of Twentieth-Century Women Writers (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985).

- Livy, History of Rome, I.9.16, in Livy in XIV Volumes, 1–2 (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press; London: William Heineman, 1962), 37–38.

- Christine de Pizan, The Book of the City of Ladies and Other Writings, ed. Sophie de Bourgault and Rebecca Kingston, trans. Ineke Harde (Indianapolis: Hackett, 2018), 136; Christine de Pizan, The Livre de la cité des dames of Christine de Pisan: A Critical Edition, ed. Maureen Curnow (Ann Arbor MI: UMI Dissertation Information Service, 1975), 866–67. I use these editions throughout for text and translation of LCD. Subsequent citations appear in parentheses in the text.

- Gail Simone, “Women in Refrigerators,” https://www.lby3.com/wir/ (accessed January 29, 2020).

- For other uses of gendered space in LCD, see Judith L. Kellogg, “Le Livre de la cité des dames: Reconfiguring Knowledge and Reimagining Gendered Space,” in Altmann and McGrady, Casebook, 126–46.

- Christine de Pizan, The Book of Deeds of Arms and Chivalry, trans. Sumner Willard, ed. Charity Cannon Willard (State College: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999). Transcription from BNF 1183, f. 49.

- Louise Rosenblatt, The Reader, The Text, The Poem: The Transactional Theory of the Literary Work (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University, 1978), 22-47.

- Though they differ from the remoter goddesses of Nature and Fortune in de Pizan’s work, precisely because they do become her friends: for the unnerving ambiguities of Nature and Fortune in Christine’s writings, see Barbara Newman, God and the Goddesses: Vision, Poetry, and Belief in the Middle Ages (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003), 115–22.

- I am grateful to the insights of Lauren Rebecca King, whose promising dissertation on identification and interventional reading in Christine de Pizan and Geoffrey Chaucer has been a guide to my own thinking.

- Boccaccio uses the first hundred of his biographies upon notable ancient pagan women, and then moves to Christian and medieval times with the last six: Pope Joan, Irene of Constantinople, Gualdrada, Constance, Camiola, and Joanna, queen of Jerusalem: Boccaccio, Famous Women, trans. Virginia Brown (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003).

- Zimmerman, “Memory’s,” 57; James Laidlaw, “Christine and the Manuscript Tradition, in Casebook, 231–51; Nadia Margolis, “Modern Editions: Makers of the Christinian Corpus,” in Casebook, 251–70; Susan Groag Bell, The Lost Tapestries of the City of Ladies: Christine de Pizan’s Renaissance Legacies (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004).

- Bell, Lost Tapestries, 6–7.

- Orlanda Soei Han Lie, Christine de Pizan in Bruges: Le Livre de la Cite de Dames as Het Bouc van de Stede der Vrauwen, London, British Library, Add. 20698 (Hilversum: Verloren, 2015).

- This volume, Verini, “Sisters and Friends.”

- This volume, Anderson, “Afterword.”

Chapter 10 (197-218) from Women’s Friendship in Medieval Literature, edited by Karma Lochrie and Usha Vishnuvajjala (Ohio State University Press, 07.11.2022), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported license.