A chilling melancholia.

By Dr. Amin Alsaden

Curator, Scholar, and Educator

Introduction

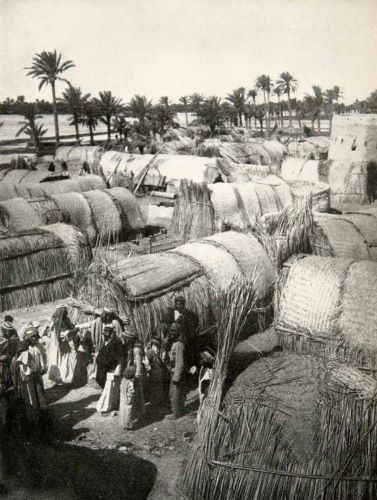

Many lived on the margins in modern Baghdad. Wealth remained in the hands of a small segment of society, even when a dazzling development campaign launched in the early 1950s and fueled by enormous oil revenues, was ostensibly meant to improve the lives of all Iraqis. Poverty existed within the capital itself, but it was most obvious at its periphery, especially in the areas known as Al-Sara’if, informal settlements built from readily available materials, such as mud, reeds, and palm tree fronds. In these slums, in today’s terminology, lived immigrants from other provinces, mostly peasants who sought a better life in the city.

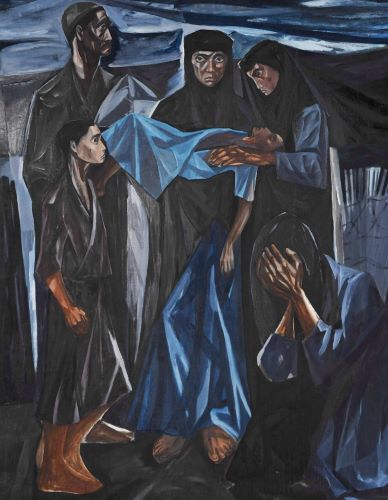

In The Death of a Child, Mahmoud Sabri evokes such a place. The artist, up until that moment, had engaged with his immediate context, Baghdad, but he does not present an urban scene here. In the flat planes of central Iraq, the trapezoidal black form seen in the painting’s indeterminate background denotes a Bedouin tent. But other clues suggest a more agrarian setting: the shovels held by the three standing men and the two light blue structures in the middle, with their repetitive patterns, reminiscent of a hasirah mat, or perhaps a more rigid siyaj, a fence made from the stems of palm tree leaves, both used in building makeshift houses in Al-Sara’if and the surrounding countryside.

Bedouin tents are usually constructed with stretches of course textiles weaved out of camel or goat hair. Nomadic communities in Southwest Asia have lived in these durable but light structures for as long as they have roamed the desert. An example can be seen below, in the background of the painting by Iraqi artist Faik Hassan. A hasirah, or bariah, is a sheet woven from palm tree fronds or reeds, used as rugs, or depending on their strength, as coverings for furniture and lighter structures. A siyaj is an Arabic word for fence or barrier.

But the shovels might be out to dig a grave. The painting depicts anonymous members of a community gathered after the loss of a child. The haunting work captures a human tragedy that could resonate across cultures, but it is quite particular in tackling a serious problem that plagued mid-20th-century Iraq: the plight of the destitute who were forgotten, underrepresented in both politics and art, in an otherwise affluent country. Sabri painted numerous works of peasants and workers who toiled endlessly, whether in urban centers or farming communities, the everyday people who endured wretched lives. It was in the early 1960s, however, living between Moscow and Prague, that Sabri created more ambitious works that immortalized scenes from contemporary Iraq.

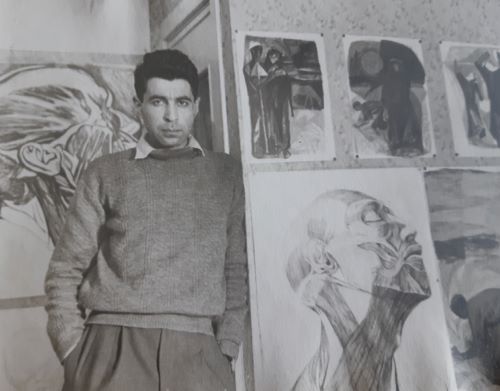

Reflecting Context

Sabri, a self-taught artist, moved to the Soviet Union to pursue formal art education after the 1958 coup d’état in Iraq, which was seen by those who benefited from the old regime, the British-backed monarchy, as a devastating event. For many others, it became known as the July 14th Revolution, an uprising that ended colonialism and aimed at self-determination for the Iraqi people with the establishment of a republic. The subsequent 1963 Ba’athist-led coup, after which Sabri decided to move to Czechoslovakia, was perceived by the artist and contemporaries as a regression, jeopardizing what was accomplished under the first republic. He explored themes of popular struggle, martyrdom, and the national quest for liberation around that time; it became especially important to underline how tyranny affected those who were most vulnerable.

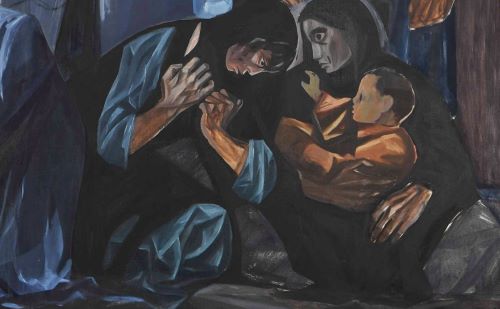

In this somber painting, a balanced composition is roughly divided into two vignettes—indicated by an interruption in the sky, a line that continues in the edge of the background structure to the right—with two separate but contiguous groups. There is vertical repetition, as though reiterating the misery, with the dead child as the only horizontal exception. The standing figures fill each end of the pictorial space, which is anchored by the rounded shapes of the crouching figures. The scene is crowded, as though cut from a longer continuous frieze about grief. The scale of the canvas (the height of the painted adults is approximately that of life-size children) is akin to a window onto another, bleak world. In that flattened space, the figures are physically close to the viewer, about to step out. The proximity brings forward their ordeal into the space of the viewer, who becomes part of the gathering.

A chilling melancholia casts its shadow on The Death of a Child. The tones of blue in the scene echo those of the gloomy dark sky, further complemented by blacks, grays, and browns. It is a dim scene, reflecting the end of the child’s life: a twilight, literal and metaphorical. What is being regarded, Sabri conveys here, are the fringes—social, geographical, and even perceptual—known by everyone, but deliberately obscured. Not only are there no extraneous details, no ornaments or ostentation of any kind, there is also hardly any texture, making these people seem like ghosts that lack tactility and substance.

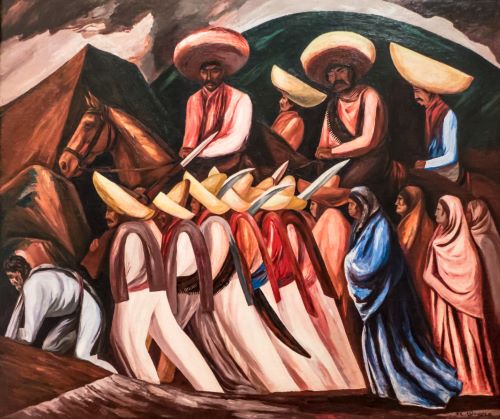

This can be contrasted with other renowned works by Sabri from around this time, such as Funeral, with their predominantly fiery red-orange colors, which spoke to Iraq’s upheavals, and might have been incendiary, intended to provoke a public outrage. Some elicit the production of Mexican artists whom Sabri admired since the beginning of his career, such as José Clemente Orozco and Diego Rivera.

Layered References

The dead child’s immediate family are likely those in the above vignette, with the rest of the community convening to console them. The woman carrying the corpse could be the mother, as suggested by a similarity in an earlier painting by Sabri, Rural Family, depicting a sick or deceased child. This woman is given prominence, as hers is the only face looking in the viewers’ direction, and by far the most expressive visage. Her glum expression betrays righteous rage, and she appears to look beyond, above the viewers’ shoulders, as though reproachfully avoiding eye contact. And unlike the otherwise gendered representations, with the women pictured as susceptible to their emotions, with heads inclined downward, hers is defiantly held up high, with a mysterious light behind, a subtle halo stressing her difference.

There are culturally specific references that would have been understood by Iraqis, and which might provide further insight into who this woman might be. Each of the men is wearing a dishdashah, apparently tied at the waist, a farmers’ custom. The two men to the right wrap a ghutrah without agal around their heads, as protection from the harsh sun while working, which suggests they took a break to be present here. The man to the left, possibly the father, is wearing an ‘araqchin, having taken off his ghutrah (it can be seen in front of his shovel), a sign of mourning over his child. Each of the women dons a plain dress, thawb, and a black shailah, with some wearing an abayah. But the more structured headdress on the woman carrying the dead child is an ‘usbah, implying this is an elder.

A dishdashah in Iraqi dialect, also known as a thawb or kandurah, is usually a white-colored, ankle-length cotton shirt or tunic worn by Arab men, mostly in Iraq and the Gulf countries. It can also be made from darker colors, especially the wool worn in winter, or from cottons typically worn by peasants for work. A ghutrah in Iraqi dialect, also known as a keffiyeh, is a square cloth headdress, usually in plain white, or patterned with black or red threads.An agal is a thick woven black cord worn on top of a ghutrah, to help secure it in place. An ‘araqchin in Iraqi dialect, also known as a gahfiyah, is a soft skull cap, plain or patterned, worn on its own, or underneath a ghutrah and agal. Also called a nafnuf, a thawb is a woman’s dress, in the dialects of Iraq and some Gulf countries. A shailah in Iraqi dialect, also known as a futah, is a black headscarf that covers the hair of Muslim women in public, worn on its own, or with an abayah. An abayah is a cloak like black garment worn by more conservative women in Iraq and different parts of the Muslim world, covering the head and clothed body. An ‘usbah in Iraqi dialect, also called a boyamah, is a piece of cloth, usually black, tied as a headband or turban on to top of a shailah.

The mother, therefore, is more likely the younger woman transfixed by pain, who tenderly lays a hand on the child’s chest and mirrors the position of the father. The front-facing woman lifts the child unnaturally high, presenting the corpse as though the body of a martyr, soliciting an answer for why such a calamity should occur in modern Iraq. She could be the grandmother, meant to conjure up an ancestral figure, or an archetypal mother. Her blue, lapis lazuli colored dress, the contrapposto posture, and the attention paid to articulating her exposed feet bear a resemblance to numerous portrayals of the Virgin Mary, a woman who sacrificed a son to the sins of humanity. The woman could also be an allegory for a nation senselessly losing its most precious people: its youth. Whatever had befallen the child—from a preventable disease, an accident due to the family’s difficult living conditions, or violence wrought by a callous regime—becomes immaterial, because Sabri is attempting to universalize the family’s tribulations.

The Christian iconography is evoked by a reference to Byzantine art, which is characterized by its elongated figures, stiff poses, and large-eyed noble faces, all channeled through the work of medieval Russian painters in whom Sabri was admittedly interested, such as Andrei Rublev and Dionisius. The term “Byzantine Empire” is a bit of a misnomer. The Byzantines understood their empire to be a continuation of the ancient Roman Empire and referred to themselves as “Romans.” The history of Byzantium is remarkably long. If we reckon the history of the Eastern Roman Empire from the dedication of Constantinople in 330 until its fall to the Ottomans in 1453, the empire endured for some 1,123 years.

Sabri’s work also brings to mind the Mannerism of El Greco, with his signature attenuated bodies. It is worth underlining that this is not naturalism or strict realism: what is represented is quite stylized. It is not about a conformity to observable things, but more about an authentic vision that the artist is constructing, along with the ideas and emotions that this mode of representation helps to emphasize.

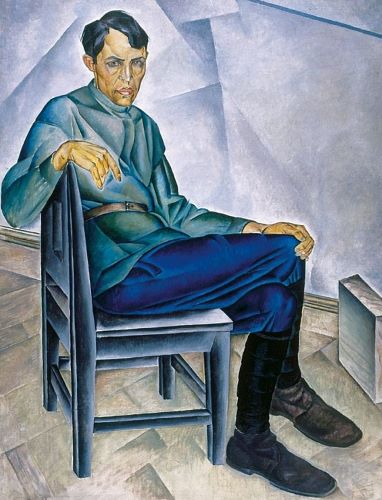

This is mostly evident in the angular volumes that underscore the dismal circumstances, and the prismatic fracturing of various surfaces, suggesting a shattered, ice-cold realm drained of comfort. The triangulation recalls some of the experiments in Cubism by avant-garde Russian artists such as Natalia Goncharova and Nathan Altman, or early works by Sabri’s teacher in Moscow, Aleksandr Deyneka.

Also in the gestural brushstrokes—the base of the canvas is visible in some places, at times creating bright contour lines that separate the forms—indexical of the raw emotions the artist wanted to elicit. This brings to mind the abrasive aesthetics of Fauvism. Sabri was interested in the French artist Georges Rouault, whose work was far more elemental. There is no sense of linear or atmospheric perspective in Sabri’s work, with the figures compressed into their nondescript environment, blended into the background thanks to his choice of colors. Their flesh is painted with those morbid gray tones, accentuating their haggard, sullen faces, devoid of vitality and joy.

The face of the woman to the bottom right is petrified, closer to that of an ancient stone sculpture, or of soil. The only anomaly in the tableau is her warmly illuminated toddler, possibly another Christ-like reference, the promise of a different future or a nod to the continuous cycle of life. Light emanates from the upper left corner, where the titular child has departed. But otherwise, there is no refinement to the anatomy, scale, or spatial distribution of the figures; the uncouth articulation of the toddler’s face or the standing adolescent boy’s feet speak of a skill that was being polished. But there is formal coherence, and the overall course quality is not only appropriate for the subject matter, but also somehow serves the artist. There is an economy of means, and the painting comes across as intentionally rugged and unfinished, as though craft and perfection are unnecessary luxuries—perhaps even deceptive, just like the modernization of Iraq.

Still, Sabri focuses on details that amplify his message. For instance, these gaunt bodies have surprisingly strong limbs. The clenched fists of the boy to the left, or the man to the far right, are menacing. The hands of the kneeling woman in the center are striking, hiding a lamenting face denied to the viewer. She gives her back to a young woman whose anguished pose, with a dejected weeping face, is equally gripping; her tense hands are pulling on her clothes, an expression of extreme sorrow in Iraq. The vigor of the painting stems from its steadfast commitment to the subject, reaffirmed through such details and the numerous layers the artist embedded in the work. But The Death of a Child must also be viewed in conjunction with others created by Sabri around this time, as if this is a series where each work completes the next.

Social Commentary

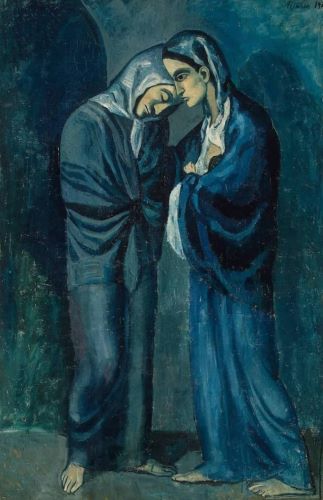

In the vein of Social Realism, usually produced by leftist artists, this painting is a critique, part of a larger commentary on issues that concern the masses (not to be confused with the official doctrine of Socialist Realism, which adopted heroic optimism in depicting life in the Soviet Union). This applies to a wide spectrum of art created during the modern period, but can also be extended to works by artists who are not normally considered under this category, and yet whom Sabri appreciated, including Vincent van Gogh and Pablo Picasso. The painting equally calls forth works by artists associated with Symbolism, such as Edvard Munch, and German Expressionism, like Käthe Kollwitz, not only in their tackling of distressing matters, but also in the highly stylized visual language they devised.

While Sabri has been commonly evaluated as an ideological rival of Jewad Selim and Shakir Hassan Al Said, the founders of the Baghdad Group for Modern Art, which was invested in synthesizing Iraq’s heritage with modernism, their interests converged significantly. At the turn of the 1950s, Sabri joined the city’s other main collective, Société Primitive (or the SP) led by artist Faik Hassan, later renamed the Pioneers Group; its members had a loosely defined agenda generally understood to be a desire to discern Iraq’s realities and capture its landscapes, so another way of situating their artistic production locally. But given Sabri’s sometimes grating rhetoric (he wrote harsh critiques of the local art milieu), there was an irony to his specific practice: a privileged artist making a career by telling the stories of humbler classes, the proletariat, within the largely elitist—bourgeoisie, to use the artist’s own terminology—art circles.

Nonetheless, Sabri’s work mobilized art’s potent expressive capacity in acts of solidarity with those who were not as fortunate or visible. It embodies a stance of resistance, a refusal of a problematic status quo. Perhaps it was not in dialogue with fashionable tendencies at the time, but it was radical in its rejection of those conventions, and in amalgamating a unique visual syntax that solidified the role of the artist as advocate and rebel. Although he strove to create a distinctive formal approach all his own, Sabri believed that an artist was not obliged to offer anything new, but to simply create compelling art that champions the causes of social justice.

Bibliography

- Amin Alsaden, “Alternative Salons: Cultivating Art and Architecture in the Domestic Spaces of Post–World War II Baghdad,” The Art Salon in the Arab Region: Politics of Taste Making, edited by Nadia von Maltzahn and Monique Bellan (Beirut: Orient-Institut Beirut, 2018), pp. 165–206.

- Bahjat Sabri Bedan, “Mahmud Sabri Bain ‘Alamain” (Mahmoud Sabri Between Two Worlds), 2008, YoutTube videos (in Arabic) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=62ffXxZZpvA, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sbznZbfqBDw, and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iOpPmscvKgg.

- Bahjat Sabri Bedan, “Shawq ila Al-Hurriyah: Dirasah li-‘Amal Al-Fannan Mahmud Sabri” (Longing for Freedom: A Study in the Works of Artist Mahmoud Sabri), 1984, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e2KjnhJFWMk and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=149wtgqHGBo.

- Hamdi Al-Tukmaji, Mahmud Sabri: Hayatuh wa Fannuh w Fikruh (Mahmoud Sabri: His Life, Art, and Ideas) (Amman: Adib Books, 2013).

- Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, Art in Iraq To-day (London: Embassy of the Republic of Iraq, 1961).

- Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, The Grass Roots of Iraqi Art (London: Wasit Graphic and Publishing Limited, 1983).

- Khalid ‘Abd Al-‘Aziz Al-Qassab, Dhikrayat Fanniyah (Artistic Memories) (London: Dar Al-Hikmah, 2007).

- Nizar Salim, Al-Fann Al-‘Iraqi Al-Mu’asir: Al-Kitab Al-Awal fi Al-Taswir (Iraqi Contemporary Art: The First Book on Painting) (Luzan: Sartec, 1977).

- Rif’at Al-Jadirji, Al-Ukhaidhir wa Al-Qasr Al-Balluri: Nushu’ Al-Nadhariyah Al-Jadaliyah fi Al-‘Imarah (Al-Ukhaidhir and the Crystal Palace: The Formation of the Dialectic Theory in Architecture) (London: Riadh Al-Rayyis, 1991).

- Shakir Hassan Al Said, Al-Fann Al-Tashkili Al-‘Iraqi Al-Mu’asir (Contemporary Iraqi Plastic Art) (Tunis: Al-Munazzamah Al-‘Arabiyah lil-Tarbiyah wa Al-Thaqafah wa Al-‘Ulum, 1992).

- Shakir Hassan Al Said, Fusul min Tarikh Al-Harakah Al-Tashkiliyah fi Al-‘Iraq, Al-Juz’ Al-Awwal (Chapters from the History of the Plastic Movement in Iraq, the First Volume) (Baghdad: Wizarat Al-Thaqafah wa Al-I’lam, Da’irat Al-Shu’un Al-Thaqafiyah wa Al-Nashr, 1983).

Originally published by Smarthistory, 11.06.2024, under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.