The spices eventually became more or less routine commodities open to many international entrepreneurs.

By Dr. James Hancock

Professor Emeritus of Horticulture

Michigan State University

Introduction

Pepper has long been the king of spices and for almost 2,000 years dominated world trade. Originating in India, it was known in Greece by the 4th century BCE and was an integral part of the Roman diet by 30 BCE. It remained a force in Europe until 1750 CE. Pepper’s pathway to Europe was a long and tortuous one, which depended heavily on who controlled the Middle East.

The Roman Routes

The most frequented route of pepper to the Roman world was via the Red Sea, first directly on Roman ships all the way from Egyptian ports to India and back, and then from the Kingdom of Axum, along the southern Red Sea. Originating in the highlands of Ethiopia, Axum became a trading juggernaut that maintained close ties with the Roman Empire and ultimately controlled northern Ethiopia, the Sudan, and South Arabia. The level of Roman trade through Axum ebbed and flowed over the years, but for the greater part of seven centuries remained strong.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 CE, a Byzantine partnership with Axum kept maritime trade links alive for a couple of centuries, but Sassanian power in the Indian Ocean grew to the point that in the 5th and 6th centuries they had almost a stranglehold on trade with India and were severely limiting the pepper trade through the Red Sea. The Byzantine Empire’s maritime link with Southeast Asia ended when it lost control of Egypt after a devastating series of wars fought with the Sassanian Empire. This effectively shut off the primary sea route of pepper deliveries to Europe.

Pepper Trade under Muslim Control

In the early 7th century, the various warring tribes of the Arabian Peninsula became unified under the Islamic Prophet Muhammad (570-632) and began to systematically take control of the whole Middle East. Over a period of just a few decades, the Arab tribesman made rapid conquests of Palestine, Syria, Iraq, Iran, and then Egypt. With their conquests, the Muslims came to control all the major trade routes from Southeast Asia. The Mediterranean became a hostile zone controlled by Arab pirates who dominated the sea for the next 300 years. Long-distance trade from the East to the West became restricted to the land-based Silk Routes passing through the northern European Steppe. In the 9th century, Trebizond, which sat on the crossroads between the Byzantine Empire, Armenia, and the Islamic caliphates, served as the major maritime outlet for the oriental spices.

Trebizond lost its central role in the 10th century when the Shiite Fatimid Dynasty took control of most of Egypt and the Byzantines began actively trading with them. The Muslims and Christians were not friends, but their trade was mutually beneficial. It was much more economical to move spices by sea than land. The western merchants traded actively in Alexandria for pepper and other spices, and in return, they provided timber, slaves, pharmacological plants, silk textiles, furniture, and even cheese.

The Rise of Venice and the Italian City-states

Over the centuries, Venetian sea power steadily grew in the Middle East while that of the Byzantine Empire gradually diminished. Trade across the Mediterranean came to be ruled by Venice and the other maritime republics that arose in Italy during the Middle Ages, including Genoa, Pisa, and Amalfi. These city-states carried on extensive trade across the Mediterranean and built strong navies for protection and conquest. Venice came to dominate the Adriatic trade, while Pisa and Genoa focused their trade more heavily on Western Europe.

As the 11th century progressed, the Muslim forces surrounding the Western Roman Empire began gaining strength and squeezing the Byzantine Empire. A new Turkic power, the Seljuk Turks, had invaded and captured Bagdad from the Abbasid Dynasty in 1055 and then went on to take the Holy Lands in Syria and Palestine from the Byzantines. They then invaded Byzantine Asia Minor, and by 1081, they had captured almost all that region. A huge slice of the old Roman Empire was now under Muslim rather than Christian control.

Fearing for their survival, the Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos (r. 1081-1118) appealed to the West for help, and in 1095, Pope Urban II agreed. He called for the First Crusade at the Council of Clermont to “liberate the Church of God”. This Crusade was remarkably successful and over a period of seven years much of the Levant was recovered and four Crusader States were established.

Having a Christian foothold in the largely Muslim Middle East had a very significant impact on western trade. The larger cities became active mercantile centers with traders in residence from Arabia, Iraq, Byzantium, North Africa, and Italy. Specialized markets arose where locals and foreigners could purchase a wide array of goods from silks and spices to basic foodstuffs, leather goods, cloth, furs, and other manufactured goods. Pepper and other spices moved freely to the West.

Between 1174 and 1187, the Ayyubid sultan Saladin (r. 1174-1193) reconquered most of the Crusader States and returned them to Muslim control. This dried up a considerable amount of the spice trade traveling through the Levant and put the emphasis back on Alexandria. The Holy City of Jerusalem fell in 1187 to the great consternation of the Christian world. The Third Crusade was launched in 1189 to recover it, and though most of the Crusader States were reclaimed, Jerusalem itself remained in Muslim hands.

In 1202, Pope Innocent III called for the Fourth Crusade to recapture the Holy City from the Muslims. The grand plan was to first invade and conquer Egypt and then go after Jerusalem. This plan went terribly off track and culminated in the madness of 1204: the sack of Constantinople by the Crusader army. All that was left of the once-proud Byzantine Empire was three rump states, the Empire of Nicaea, the Empire of Trebizond, and the Despotate of Epirus, and Jerusalem remained under Muslim control. After almost 1,000 years of European dominance, the mighty Byzantine Empire had evaporated, and the spice trade fell almost completely into the Venetians’ hands.

Final Fall of Crusader States

In April 1291, the Mamluk sultan al-Ashraf Khalil (r. 1290-1293) marched on Acre in the Kingdom of Jerusalem determined to “snuff out the infidel presence within the lands of Islam” (Crowley, 148). The city’s population of about 40,000 people came from all over Europe and included merchants from Venice and Pisa and was protected by the fabled Knights Templar and Knights Hospitaller. Khalil brought a huge army outside the walls of the city along with a number of giant catapults he had dragged from Cairo. Under relentless bombardment, the Europeans held on valiantly for five weeks, but to no avail.

Shockwaves resounded through Europe after the siege of Acre, 1291 CE, and papal recriminations followed. Venice and Genoa had long been buying silk, spices, flax, and cotton in the Islamic world. The wood for the catapults and the soldier slaves that had played a critical role in the destruction of Acre, could very well have come from the Italian traders. Pope Boniface VIII decreed in 1302 a trading ban with the Mamluks in Egypt and Palestine. This meant that the Venetians and Genoese would have to totally bypass the Muslim middleman to obtain the exotic goods from India and Southeast Asia that Europe so demanded. This meant returning to the steppe routes for their spices.

Genoa was the first of the Italian city-states to move energetically into the Black Sea region. There they set up their first major colony at Caffa, on the Crimean Peninsula in 1266. They quickly followed Caffa with a series of settlements all along the coasts of the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov, and they established a trading station in Trebizond. Caffa soon became a major international center of commerce bringing together Latino-Christian, Byzantine-Greek, Slavic, Russian, Turkic, Tatar, Armenian, Jewish, and Eastern Mediterranean cultures.

At its peak, Caffa held a population of nearly 20,000, protected by two formidable concentric walls. It served as the key transit point for trade in spices and silk coming from the East, as well as grain, fish, caviar, timber, salt, flax, hemp, leather, and meat. Caffa also became particularly important as a hub of the worldwide slave trade, exporting slaves from its Black Sea colonies to the metropolis, the rest of Italy, other regions of the Western Mediterranean, Constantinople, Asia Minor, the Near East, North Africa, and Mamluk Egypt.

Venice Moves into the Black Sea

Venice had been largely inactive in the Black Sea in the second half of the 13th century, but they became increasingly aware of its lucrative trade potential. This desire grew particularly hot with the papal decrees to stop trading with the Middle Eastern Muslims, who had been the major supplier of spices and silks to the Venetians. Genoa fought mightily to hold onto their favored position, and numerous pitched battles spilled out all across the Eastern Mediterranean and Black Sea. Ships were burned, cargos pirated, and settlements pillaged. Huge, armed mercantile fleets slugged it out, often without a clear winner.

It was not until 1333 that Venice was able to establish its first real toehold in the Black Sea region, when it sent an ambassador to the Muslim overlord Muhammad Uzbeg Khan (r. 1313-1341) who allowed them to establish a colony at Tana on the northeast corner of the Sea of Azov. The Genoese were also present at Tana, but their large galleys had difficulty in the shallow Sea of Azov. The shallow-drafted, lagoon-adapted galleys of the Venetians were able to negotiate the thin waters of Azov much easier than those of the Geneoese.

Tana, along with the Empire of Trebizond, became Venice’s major gateways to the East, connecting them to the trans-Asiatic Mongol routes carrying the precious oriental commodities: spices, silk, pearls, raw cotton, gold, furs, and jewelry. Venetian merchants became wealthy from that trade, much as the Byzantines had at Tana and Trebizond centuries earlier.

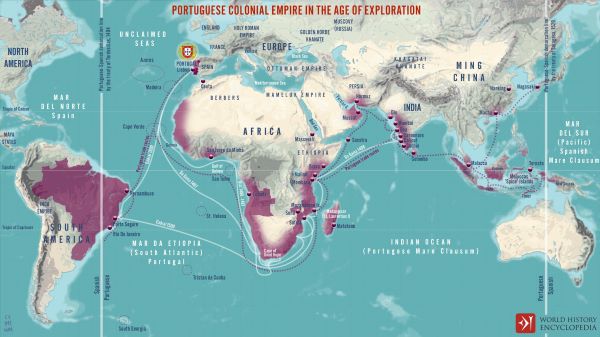

Portugal and the Age of Exploration

A seismic shift in the direction of pepper trade came with the European Age of Exploration when the Portuguese discovered the way around the Cape of Good Hope and began their bloody conquest of the Indian Ocean. In the early years of the 16th century, the Portuguese conquest of India and their takeover of Malacca dried up much of the Venetians ability to obtain spices. Venetian spice imports fell from around 1600 tons a year at the end of the 15th century to less than 500 tons a decade and a half later.

As the presence of the Portuguese grew in the Indian Ocean, the Mamluks and Venetians became obsessed with saving their lucrative trade network. The Portuguese intrusion into the Indian Ocean was a direct blow to the commercial interests of Venice, and the Venetians did everything they could to encourage the Mamluks to repel the Portuguese. They pleaded with the Mamluks to try and stop trade between the Indian city states and the Portuguese. Finally in 1505, the Mamluks decided they must take action, and Sultan Qansuh al-Ghuri (r. 1501-1516) ordered the building of a fleet to fight the Portuguese. The fleet arrived in India at Diu in 1507, and teaming up with local Indians had some initial success, but the Portuguese ultimately crushed the Egyptian-Indian coalition. The remnants of the Egyptian fleet returned to Egypt, and the Mamluks never seriously challenged the Portuguese again.

While Mamluks were not able to oust the Portuguese from India and take Portuguese Malacca, the overstretched Portuguese were never able to successfully bottle up Red Sea trade, making their early dominance in the pepper trade ephemeral. It did not take long for the Gujarati and Arab merchants to shift to other locations in Sumatra and Java for pepper to keep supplying the Venetians. By the end of the 15th century, a large percentage of the pepper headed to Europe was traveling overland across the Levant from the Red Sea rather than via the Portuguese Atlantic Route. The Venetians delivered pepper to most of Europe through this route, while the Portuguese shifted the focus of their pepper trade to northern Europe through Amsterdam. Muslim Aceh became a pepper trading powerhouse, annually producing seven million pounds of pepper.

Ottoman Takeover

The 16th century brought another great shift in the geopolitical landscape of the Eastern Mediterranean when the Ottomans established an uncontested hegemony in the region. In 1517, they defeated the Mamluks, and Egypt and Syria became provinces within their empire. In the mid-16th century, Suleiman the Magnificient (r. 1520-1566) also captured Bagdad and the lands surrounding the head of the Persian Gulf and extended Turkish power to Aden, on the Red Sea. He now completely controlled the spice trade, which by now greatly overshadowed the Atlantic trade of the Portuguese.

When the Ottoman Empire first took over Egypt, they stopped most of the Venetian trade in spices, but this embargo did not dissuade the Venetians for long. Even though the Ottomans and Venetians were bitter enemies and fought territorial wars, it was mutually beneficial to keep their trade links open. In 1528, Francis I of France (r. 1515-1547) opened negotiations with Suleiman, and French ships were allowed to obtain spices in Alexandria. The Turks came to prefer dealing with the French over the Venetians, and the French overtook the Venetians in the amount of trade through Alexandria.

Levantine Trade

In 1536, a treaty of capitulation was also negotiated between Francis I and Suleiman I that gave France jurisdiction over Levantine trade. Any other Christian nation who wanted to trade across the Levant “was obliged to do business under the French flag and under the exclusive surveillance and representation of the French ambassador and consuls” (Horniker, 302). French trade in spices and silk began to boom across the Levant. Once this trade became significant, it was inevitable that the English would find this arrangement unbearable; thus in 1583, under Elizabeth I of England (r. 1558-1603), the English were able to obtain their own treaty of peace and friendship, which gave them the privilege of trading under their own flag. The Dutch also came to be active in the Levant, first under French and English colors and then receiving their own capitulation in 1612. During the Twelve Years’ Truce between the Dutch Republic and Spain (1609-1621), the Dutch were able to outplay their Venetian and English rivals and became the major player in the Levant trade.

In the early 17th century, the energetic Dutch and English finally found their way around the Cape and reinvigorated the western traffic in spices, which had greatly decayed under Portuguese control. They fought mightily between each other for the pepper, nutmeg, and clove trade, in which the Dutch ultimately got the upper hand. They further strengthened their commercial relations with the Levant, and they even began bringing pepper and spices around Africa to Levantine ports. By this time the Venetians’ fortunes had plummeted, while the French held firm onto their slice of the pie.

End of the Spice Era

In the middle of the 17th century, changes in European tastes caused the profitability of the spices to plummet. Interest in new stimulants, beverages, and textiles took over the market in Europe. There was an oversupply of pepper by the middle of the century, which dropped prices by about 40% compared with that which the Portuguese and then the other European powers had long been able to maintain. After a peak of seven million kilograms of pepper imported in 1670, levels fell to about 3.5 million kilograms in 1688. With the end of the East India companies, so went the centralization of the pepper and spice trade. No longer would the spices be grown solely in restricted geographical regions under the control of a specific trading company. They became scattered all over the world. Many now are grown and important in countries far from their Southeast Asian origins, in particular Africa, Central America, and South America.

So, after thousands of years as remote, localized commodities controlled by a few powerful trading empires, the spices became more or less routine commodities open to many international entrepreneurs. For centuries after the Europeans first found their way to the Indian Ocean, the pepper-producing countries remained static, and this situation remained unchanged until the modern era when pepper was successfully introduced to Brazil in the 1930s, and to Africa, Vietnam, and southern China after World War II (1939-1945). Vietnam leads world production today, followed by Brazil, Indonesia, and India.

Bibliography

- Adelson, H.L. . “Early Medieval trade routes.” The American Historical Review , 65, pp. 271-287.

- Anonymous. The Long Morning of Medieval Europe. Routledge, 2021.

- Apicius & Vehling, Joseph Dommers. Cookery And Dining In Imperial Rome. Martino Fine Books, 2012.

- Asbridge, Thomas. The Crusades. Ecco, 2011.

- Boxer, C.R. Portuguese Seaborne Empire. Carcanet Press Ltd., 1991.

- Butzer, K.W. . “Rise and fall of Axum, Ethiopia: a geo-archaeological interpretation. .” American Antiquity , 46 , pp. 471-475.

- Crowley, Roger. City of Fortune. Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2013.

- Horniker, A.L. . “Anglo-French rivalry in the Levant from 1583 to 1612.” Journal of Modern History, 18, pp. 289–305.

- Iran Chamber Society: History of Iran: The Persian Gulf Trade in Late Antiquity Accessed 1 Sep 2021.

- Khvalkov, E. . The colonies of Genoa in the Black Sea region: evolution and transformation. PhD thesis, European University Institute, Florence, Italy , 2015

- Krondl, Michael. The Taste of Conquest. Ballantine Books, 2008.

- Lane, F. “The Mediterranean spice trade: further evidence of its revival in the sixteenth century.” . The American Historical Review , 45, pp. 581-590.

- Saudi Aramco World : The Coming of the Portuguese Accessed 1 Sep 2021.

- Wheelis, M. “Biological warfare at the 1346 siege of Caffag Infectious Diseases .” Emerging Infectious Diseases , 8, pp. 971-976.

Originally published by the World History Encyclopedia, 09.28.2021, under a Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.