The mob cut telephone lines, surprised prison guards, and seized Leo Frank.

Introduction

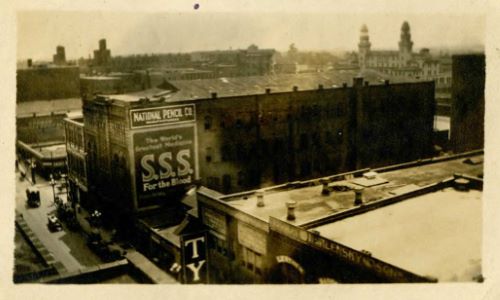

On April 26, 1913, Confederate Memorial Day, thirteen-year-old Mary Phagan was murdered at the National Pencil Company in Atlanta, Georgia. Leo Frank, the Jewish, New York-raised superintendent of the National Pencil Company, was charged with the crime.

At the same time, Atlanta’s economy was transforming from rural and agrarian to urban and industrial. Resources for investing in new industry came from Northern states, as did most industrial leaders, like Leo Frank. Many of the workers in these new industrial facilities were children, like Mary Phagan.

Over the next two years, Leo Frank’s legal case became a national story with a highly publicized, controversial trial and lengthy appeal process that profoundly affected Jewish communities in Georgia and the South, and impacted the careers of lawyers, politicians, and publishers.

By the early twentieth century, Jewish communities had become well-established in most major Southern cities, continuing a path of migration that began during colonial times. The Leo Frank case and its aftermath revealed lingering regional hostilities from the Civil War and Reconstruction, intensified existing racial and cultural inequalities (particularly anti-Semitism), embodied socioeconomic problems (such as child labor), and exposed the brutality of lynching in the South.

Setting: Atlanta in 1913

North/South Dichotomy

In 1913, Atlanta was less than fifty years removed from the Civil War. Economic divides and resentments between North and South remained. The siege and burning of Atlanta, Sherman’s March to the Sea, and Reconstruction were bitter memories for many Southerners, and the Southern economy still lagged behind the rest of the country.

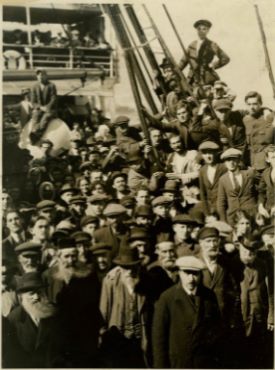

People and industry from the North migrated to the South after the Civil War. Many Northerners who came to the South did so for economic reasons, and brought with them capital and experience. Although the money was welcome, Northerners who owned businesses were often resented and deemed “carpetbaggers” and “scalawags.”

Resentment of Northern-controlled industry is exemplified by this quote from the Atlanta Constitution on April 27, 1913, by Dr. Charles Lee: “Our principles were not defeated when we surrendered at Appomattox. . . .There are other enemies, bitter ones, that must be fought—emigration, labor, the double standard of child labor and white slavery. . .” In this historical re-imagining, slavery becomes the crisis of child and female exploitation created by outsiders, but against which native-born white Americans from North and South could ultimately unite.

In Southern states, the Confederacy was cherished and romanticized. Confederate Memorial Day, established in 1874 and observed in Georgia on April 26, annually featured parades with Confederate veterans. In 1913, Georgia’s Confederate Memorial Day fell on a Saturday and a large parade was held in Atlanta to celebrate the holiday.

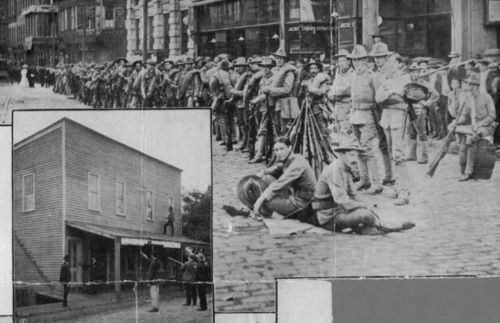

Racial Violence

Racial tension in Atlanta exploded during a violent race riot in 1906, caused by sensationalist press reports (none verified) of white women attacked by African American men. White mobs attacked African Americans in streets, homes, and businesses over several days. Martial law was declared and state militia restored order. Dozens of African Americans were killed; many more were wounded.

In 1913, Atlanta’s population was one-third African American. Jim Crow laws mandated segregation for African Americans in all areas of life, denying them the right to vote and access to public areas and accommodations while discriminating against them in housing and employment. Jim Crow laws were the legal means of counteracting the freedoms that African Americans obtained after emancipation and the passage of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. And often, they were supplemented and enforced using an extralegal method —lynching.

All African Americans were expected to act deferentially to white people; refusal could result in violence. Most lynching victims were African American men. Lynchings were horrific spectacles witnessed by large crowds that included children; the victim was often brutally tortured first. Accusations of rape were often impetus for lynching, but lynchings could also occur whenever an African American was accused of violating a Jim Crow law.

Economic Transformation and Child Labor

In 1913, Atlanta’s economy was transforming from agrarian to industrial. From 1900 to 1905, Atlanta manufacturing increased by seventy-five percent, and the city had become a hub for transporting agricultural products. While the state of Georgia remained primarily rural and agrarian, Atlanta was becoming an urban, industrial city. A symbol of Atlanta’s new industrial growth, the Fulton Bag and Cotton Mills was one of Atlanta’s largest employers in 1913. It was owned by the Elsas family, prominent members of Atlanta’s Jewish community.

Economic development in Atlanta was promoted by Henry W. Grady, managing editor of the Atlanta Constitution. He solicited Northern investment in Southern business by emphasizing the appeal of accessible Southern labor and selling Atlanta as part of the “New South.” Grady’s “New South” emphasized the industrial progress that underscored the distance from the Civil War and it concealed violence employed to maintain a familiar racial order.

Working conditions in many Southern manufacturing facilities were difficult. Factories were hot in summer, cold in winter, and sanitary conditions were poor. But the issue most prevalent in 1913 was child labor. While most Southern states set a minimum age of twelve for child workers, on April 26, 1913, the Atlanta Georgian reported that Georgia’s child labor standards were the nation’s worst, with factories employing children as young as ten.

The National Pencil Company in Atlanta exemplified these industrial conditions: the factory was supervised by Leo Frank, a Northerner, and Southern girls like Mary Phagan were hired to work low-wage jobs.

Idealization of Women

In 1913, some white Southerners still sought the restoration of antebellum culture of honor, particularly what they had lost during the Reconstruction era. They clung to ideals of womanhood that glorified virtue and purity. A model Southern lady was virtuous, modest, and pious. She was happy to maintain a home, raise children, care for the sick, sew, tend a garden, and be a dutiful wife. Male investment in this ideal was so pronounced that preserving the characteristics of Southern “belles” was considered a means of preserving Southern honor.

Women far outnumbered men in Georgia after the Civil War, and many were forced out of economic necessity to labor alongside men as sharecroppers, tenant farmers, or as mill and factory laborers. Their position as laborers contradicted the deep-seated ideals of white Southern womanhood that remained in the collective mindset, and thus, the ideal of Southern womanhood faced challenges.

Any perceived challenge to Southern honor regarding girls and women could result in violence from mobs or organized groups. The Ku Klux Klan’s oath even included the phrase “to be of special protection to female friends, widows, and their households,” conflating their resistance to economic and political change in the South with the sexuality of white women.

Jews and Anti-Semitism

Jews first immigrated to Atlanta in the 1840s, soon after the city was founded. They came from Germany, and from coastal cities like Savannah and Charleston. Savannah’s Jewish settlers had established the first congregation in the South.

Most of Atlanta’s Jewish community was comprised of merchants, who emblemized Henry W. Grady’s “New South” vision to stimulate Southern industry by cooperating with Northern enterprises. As their businesses thrived, the Jewish population in Atlanta grew from 26 to 4,000 between 1850 and 1910. And by 1910, Jews comprised 2.6 percent of Atlanta’s population.

Southern Jews occasionally found that economic and social changes contributed to the rise of anti-Semitic rhetoric and attitudes that portrayed them as outsiders. They were often held responsible for disappointments in times of crisis and uncertainty, such as the loss of the Civil War and agricultural depression in the late nineteenth century.

Such anti-Semitic resentment also appeared in the early twentieth century. Fear of the technological and social changes brought about by industrialization gave impetus to the Populist movement, which included its share of spokespersons who blamed Jews for financially exploiting farmers and laborers. Among those Populists was US senator and newspaper editor, Thomas E. (Tom) Watson.

Crime and Trial

Crime and Arrest

Confederate Memorial Day fell on Saturday, April 26, 1913. The National Pencil Company in Atlanta, Georgia, was closed, but superintendent Leo Frank was in the office working on a financial report and handing out wages. Thirteen-year-old employee Mary Phagan collected her pay around noon; she did not return home.

In the early hours of April 27, African American night watchman Newt Lee discovered Phagan’s body in the factory basement and immediately called the police. Phagan had been strangled and dragged across the floor. Two crudely written notes implicating “a negro” were found nearby. Initial suspicion fell on Lee. When Leo Frank was contacted about the murder, the police noted he was very nervous. But when he was brought in for questioning, Frank denied knowledge of the crime.

The National Pencil Company’s sweeper, an African American man named Jim Conley, was discovered washing a bloody shirt and was also questioned by police. He denied any involvement, claiming he could not read or write. But after intense interrogation, Conley’s story changed. He admitted writing the notes, but claimed that he did so upon orders from Leo Frank. Despite the inconsistencies in Conley’s story (which changed four times), the police and solicitor general Hugh M. Dorsey believed him. Leo Frank was arrested and indicted for the murder of Mary Phagan. Jim Conley was the primary witness.

Major Participants

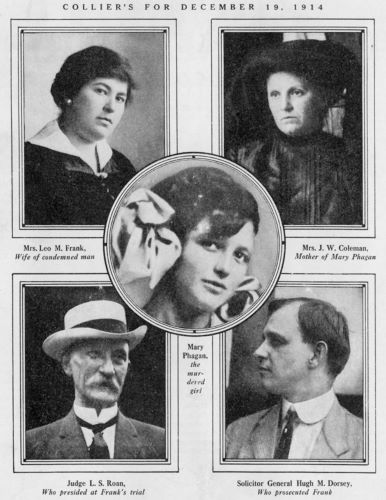

Leo Frank’s trial took place from July 28 to August 26, 1913. Major participants included:

- Jim Conley: sweeper at National Pencil Company; primary witness for prosecution.

- Hugh M. Dorsey: solicitor general (prosecutor) for the Atlanta Judicial Circuit. Dorsey worked closely, although not always harmoniously, with police to prepare their case.

- Leo Frank: defendant

- Lucille and Rae Frank: Frank’s wife, Lucille, and his mother, Rae, attended each day of the trial. Both women publicly professed their belief in Frank’s innocence and criticized the investigation.

- Newt Lee: night watchman at National Pencil Company; Lee discovered Mary Phagan’s body.

- Alonzo Mann: Frank’s office boy and a character witness.

- L. S. Roan: judge assigned to case.

- Luther Rosser and Reuben Arnold: lead defense attorneys. Rosser had an outstanding reputation as a trial lawyer who specialized in cross-examination.

- William Smith: Conley’s attorney; prepared Conley for cross-examination.

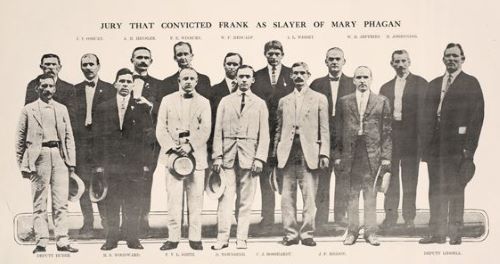

- Jury: composed of all white men.

- Crowds: standing-room only, plus many more outside the courtroom. The crowd, which favored the prosecution, responded loudly to some court actions.

Prosecution

Jim Conley was the primary witness for the prosecution. His testimony was so lurid that Judge L. S. Roan removed women from the courtroom. Conley claimed to serve as a lookout for Frank while he had sexual relations with young girls, and that Frank had even established signals for Conley to lock and unlock his office.

Conley stated that Frank commanded him to “watch out” when Mary Phagan arrived. Shortly after, Conley heard a scream. When Conley was signaled to unlock the door, a shaken Frank said that Phagan accidentally hit her head while resisting him. According to Conley, Frank first asked for help moving her body, then together, Conley and Frank dragged Phagan into a corner of the basement. After returning to the office, Frank dictated notes and ordered Conley to place them near Phagan’s body. Conley said that Frank then bribed him to “keep his mouth shut.”

Frank’s attorneys vigorously attacked Conley, who admitted lying initially, but ultimately held to his assertions. Unable to break Conley’s testimony, the defense moved it be stricken from the record. When Judge Roan denied the motion, cheering broke out in the courtroom, prompting Roan to threaten vacating the room if order was not restored. Solicitor Hugh M. Dorsey soon rested the state’s case.

Defense

Leo Frank’s lawyers challenged Jim Conley’s credibility, demonstrated that Frank did not have time to commit the crime, and collected testimony from multiple character witnesses. This was followed by a four-hour statement from Frank.

Frank’s defense drew attention to Conley’s lies and criminal record. Witnesses testified to Conley’s dubious behavior, particularly on April 26, the day of the murder. By showing detailed account sheets Frank was working on that day, the defense argued Frank was too preoccupied to do what Conley had claimed. Numerous witnesses testified to Frank’s good character, including Alonzo Mann, Frank’s office boy. Mann stated that he worked April 26, but did not hear or see Frank do anything unusual.

Finally, Frank took the stand. He spoke calmly but firmly, asserting Conley’s tale was fabricated, and that detectives distorted his statements to incriminate him. Frank admitted to being nervous after hearing of the murder, noting that any man in his position would be. He stated that Phagan came in for her pay soon after noon, left his office, and he never saw her alive again. He worked on a financial report, and then went home. He never saw Conley that day.

Soon after Frank’s statement, the defense rested.

Sentence, Appeals, Commutation, and Lynching

Conviction and Sentence

In final arguments, solicitor Hugh M. Dorsey—in support of the prosecution—painted Frank as a Jekyll and Hyde figure. Conversely, the defense team of Reuben Arnold and Luther Rosser claimed Frank was an honest, upstanding citizen who was a victim of anti-Semitism, and emphasized that the real perpetrator was Jim Conley.

Dorsey had the last word, and with it he destroyed Frank’s character and portrayed Phagan as a symbol of lost innocence. By referring to great Jewish historic figures in his closing statements, he deflected charges of anti-Semitism and asserted that Frank’s deviant behavior dishonored the Jewish people and the girl he was accused of brutally murdering. Dorsey’s words were relayed to the crowd outside and greeted with thunderous applause.

Before the verdict was read, Judge Roan consulted Frank’s attorneys. Fearing mob violence if the jury acquitted Frank, they mutually agreed neither they nor Frank should be in court when the decision was read out. The jury deliberated less than two hours before returning a guilty verdict. When Dorsey emerged from the courthouse, he was cheered and carried on the shoulders of the crowd. Informed of the verdict, Frank again proclaimed his innocence.

Judge Roan sentenced Frank to hang.

Appeals and Commutation

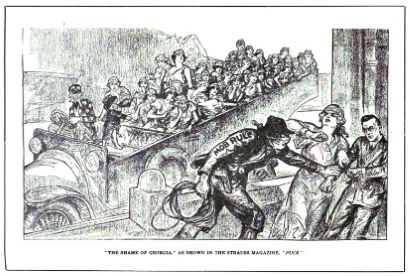

Over the lengthy appeals process, the Leo Frank case became a national cause. Northern newspapers, primarily The New York Times and Collier’s Weekly, argued Frank’s innocence amid nationwide expressions of anti-Semitism.

This angered many Georgians, particularly Tom Watson, populist politician and publisher of Watson’s Jeffersonian Magazine. When national publications attacked Georgia, Watson retaliated by disseminating sensational, anti-Semitic editorials that turned public opinion against Frank, and depicted the support of Frank’s appeals process as meddling from Northern and Jewish interests.

Ultimately, Georgia governor John Slaton bore the responsibility for deciding whether Frank would hang or if his sentence would be commuted to life imprisonment. Slaton received letters urging commutation from Jim Conley’s attorney (who was convinced of his client’s guilt) and Judge Roan, who had presided over the Frank case. He also received letters against commutation, including one from a group of city leaders from Mary Phagan’s hometown of Marietta. Slaton agonized over the decision: he read trial documents, visited the crime scene, and ultimately commuted Frank’s sentence on his last day in office. Knowing the decision would be unpopular, Slaton left Georgia, and did not return for ten years.

After the commutation, Frank was moved to the state prison farm near Milledgeville, Georgia.

Lynching

The commutation of Leo Frank’s sentence by Governor Slaton in June of 1915 infuriated many Georgians. Publisher Tom Watson’s editorials inflamed public opinion, and circulation of his publications, including Watson’s Jeffersonian Magazine, more than tripled.

A group of Marietta, citizens, including a former governor, state judge, and several leading businessmen who had written and spoken publicly against Frank’s commutation, carefully organized, planned, and—it is believed—bribed or intimidated prison officials.

On the evening of August 16, 1915, eight vehicles arrived at the state prison farm in Milledgeville. The group cut telephone lines, surprised guards, seized Frank, and returned to Marietta on back roads. One vehicle acted as a decoy.

Reaching Marietta by dawn of August 17, 1915, Leo Frank was hanged from an oak tree in a grove not far from Mary Phagan’s home. Photographs were taken of his body hanging from the tree—they were later made into souvenirs. No one was ever prosecuted for the lynching.

In the South during this period, Leo Frank’s lynching was unusual because the majority of lynching victims were African American men. These lynchings took many forms: spectacles with giant crowds and secret violence perpetrated by night; carefully planned attacks and more spontaneous murders; plans developed by influential citizens and plots executed by large mobs. Frank’s lynching was not necessarily unique in its precise planning by important citizens and secret execution, but it received more national attention than the thousands of anonymous African American men lynched during the same period because Frank was a Jew.

Reaction to Lynching

The Northern reaction to Frank’s lynching was immediate and critical of the breakdown of law in Georgia, and at the failure to prosecute the men who were responsible. The San Francisco Bulletin printed:“Georgia is mad with her own virtue, cruel, unreasoning, blood-thirsty, barbarous. She is not civilized. She is not Christian. She is not sane.”

The reaction in Georgia was different. Most white Georgians felt justice had been served.

From the Milledgeville Union-Recorder: “The real truth about the matter is about 90 per cent of the white people of Georgia believed Frank guilty, and believed that under the operation of the law his life was justly, legally, and righteously forfeited.”

But there were also voices of opposition. Many saw the lynching as a manifestation of the intense anti-Semitism in the region exacerbated by Tom Watson’s writings in Watson’s Jeffersonian Magazine and similar publications. New South capitalists and elite Georgia progressives publicly disdained the vigilantism of the lynching, which they saw as a threat to the stability of industrialism and urban growth that they championed. And although African Americans were frustrated by the outburst of sympathy for Frank amidst white apathy to hundreds of African American lynchings, the African American press condemned the lynching as a familiar act of policing racial boundaries because Jews were considered a non-white racial group during this period.

Legacy

Anti-Defamation League and Ku Klux Klan

The Leo Frank case catalyzed significant growth of several sociopolitical organizations of the day, including both advocates for and against racial violence. The first of these was the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith (ADL), founded in 1913 by Sigmund Livingston, a Chicago attorney—the same year as the Leo Frank trial. Although the creation of the ADL preceded the Leo Frank case, Frank’s experience bolstered Livingston’s belief that American Jews needed an organization that would challenge American anti-Semitism. The ADL remains an influential civil rights organization.

The second was the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), which was revived in Georgia at the end of the Frank case. Originally founded after the end of the Civil War, the KKK had been shut down by federal intervention during Reconstruction. Inflammatory editorials penned by Thomas Watson soon after Frank’s lynching incentivized the newly formed Klan, who burned a cross on top of Stone Mountain on Thanksgiving Day, 1915, to signify the organization’s rebirth. Several members of Leo Frank’s lynching party were also charter members of the new Klan.

The Klan’s white supremacist, anti-Semitic, anti-Catholic, and anti-immigration platform secured political influence in Georgia and nationwide—the KKK reached an estimated membership of five million people by the mid-1920s. Internal feuding and the exposure of Klan violence by journalists who infiltrated the organization eventually led to a steep decline in the group’s political influence by the late 1940s.

Careers

The Leo Frank case impacted the careers of people involved with it.

Two whose careers advanced:

- Hugh Dorsey was relatively unknown before the trial. Before the Frank case, Dorsey had lost two highly publicized cases. But his victory in the Frank case propelled him upward. Dorsey was elected governor in 1916, and re-elected in 1918. Perhaps surprisingly, he was a progressive who openly campaigned against mob violence.

- Tom Watson: With his editorials on the Leo Frank case, circulation of Watson’s Jeffersonian Magazine and The Jeffersonian increased dramatically. From this, Watson gained some wealth. Elected to the United States Senate in 1920, he died in office.

Two whose careers were damaged:

- John Slaton, a popular governor and one-time favorite for a US Senate seat, saw his political career end with his commutation of Frank’s sentence. Threatened by mob violence, Slaton and his wife fled Georgia. He eventually returned, but never sought political office again.

- William Smith, Jim Conley’s attorney, had misgivings about the sentencing of Frank. He had carefully studied the evidence, and concluded that his client, in fact, was guilty of Phagan’s murder. His letter to Governor Slaton was instrumental in the decision to commute Frank’s sentence. Unpopular because of this stance, he lost his legal clients, and later spent time working at shipyards in Virginia and New York.

Atlanta’s Jewish Community

Leo Frank’s lynching terrorized Georgia’s Jewish communities. Atlanta Jews, who had worked hard to assimilate into Southern society since establishing themselves prior to the Civil War, were now convinced that they were not safe from anti-Semitism. Many withdrew from public life, and Jewish leaders were pressured to appear conciliatory so as not to arouse hostility. No Jewish candidates ran for public office in Atlanta for twenty years; some Jews felt it necessary to leave the South altogether.

By the mid-1940s, Atlanta’s Jewish leaders emerged with more outspoken views. Jacob Rothschild was rabbi at Atlanta’s oldest synagogue, the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation, also known as “the Temple.” Rothschild openly criticized segregation, and publicly supported the civil rights work of Martin Luther King, Jr. His outspokenness was challenged violently when the Temple was bombed by white supremacists in 1958. This time, however, Atlanta rallied to support its Jewish community. Led by Mayor William B. Hartsfield and Atlanta Constitution editor Ralph McGill, Atlantans immediately condemned the incident and campaigned to rebuild the Temple.

During this time, the Southern Israelite, which began as a Temple bulletin, expanded into a monthly newspaper. It ultimately began circulating statewide and throughout the South, and was a leading Jewish publication.

Pardon and Public Opinion

At the time of the trial, most Georgians believed Frank was guilty. In the years following the Leo Frank case, Northern newspapers, particularly The New York Times, published numerous articles that emphasized Frank’s trial was unfair. These pieces angered many Georgians who resented the challenge of Southern courts by Northern journalists.

The African American press also rejected white newspaper coverage of the Frank case. This came partly because the white press employed the same racist caricatures of Jim Conley that the Frank defense team had resorted to, and partly in exasperation that a white man’s lynching received so much more publicity than the lynchings of hundreds of African American men.

In 1982, Frank’s former office boy, Alonzo Mann, signed an affidavit stating he saw Jim Conley carrying Mary Phagan’s body the day of her murder. Based upon this revelation, the Anti-Defamation League applied for a posthumous pardon for Frank from the Georgia State Board of Pardons and Paroles. The application was denied in a ruling that stated Mann’s testimony did not conclusively prove Frank’s innocence.

The ADL applied again, based on Georgia’s failure to protect Frank. This pardon was granted in 1986. The pardon did not address Frank’s guilt or innocence, only the state’s failure to protect him.

The exhibition was created by the Digital Library of Georgia (http://dlg.galileo.usg.edu/). Exhibition Organizers: Charles Pou, Mandy Mastrovita, and Greer Martin.

Published by the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA), November 2015, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.